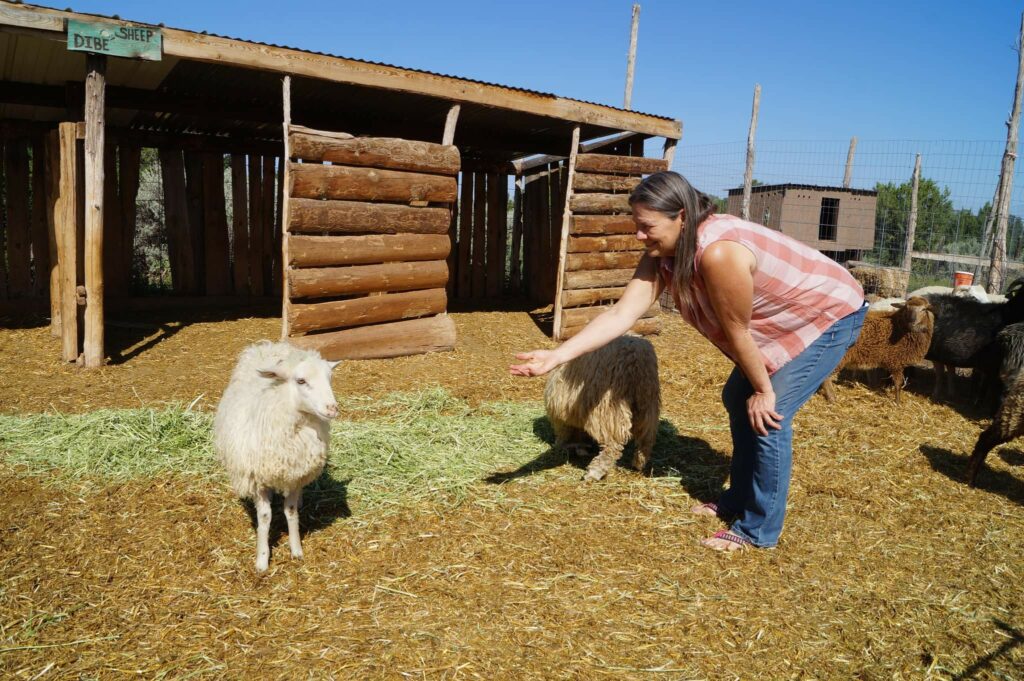

Drive a few miles off the dusty, red dirt Cousins Road in Vanderwagen, New Mexico, and you’ll find an unusual microclimate hiding in plain sight. The area sits at a towering elevation of 7,149′ above sea level, a region known for brittle, desert conditions that make farming seem like an impossible feat. The first time I entered Spirit Farm, an indigenous-led regenerative teaching farm, expansive rows of supple vegetation and healthy livestock were in abundance. But just seven years ago, the desertified, overgrazed area resembled scorched earth.

James and Joyce Skeet founded Spirit Farm in 2014 as a way to reclaim indigenous spiritual and farming practices while incorporating modern techniques to create adaptability and resilience despite the harsh growing conditions around them. Among the farm’s many efforts, the Skeets hope to inspire other indigenous communities around Spirit Farm to grow their own food sources—one component of health disparities that are tied to historical racial injustice. But the path to reentering a relationship with nature’s systems hasn’t been an easy road.

“When we moved back to this land, the soil had bad bacteria. My grandfather deeply plowed from one acre to the next for a number of years until he exhausted the soil. We didn’t know that until we ventured into soil science. Soil science collaborating with indigenous science is very important because it allows the images and the storytelling to fuse with the research and the numbers crunching. We’d love to go all indigenous, but we can’t because colonization has hampered the passing down of generational wisdom.”

The question climate scientists should be asking indigenous communities is: ‘Can you explain more about what you have done in 40,000 years?’ Instead of going to the tech community and asking ‘What’s the latest science technology and how can we exploit that?

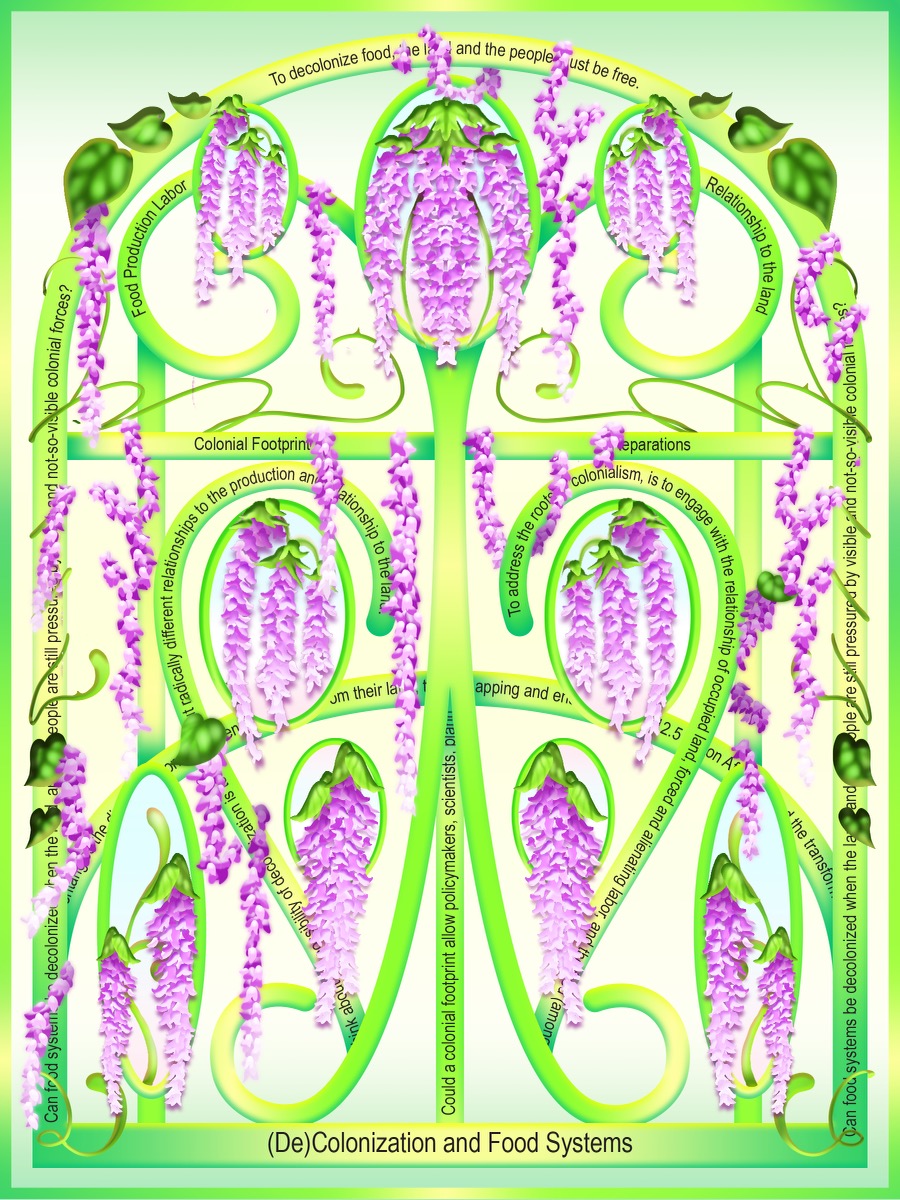

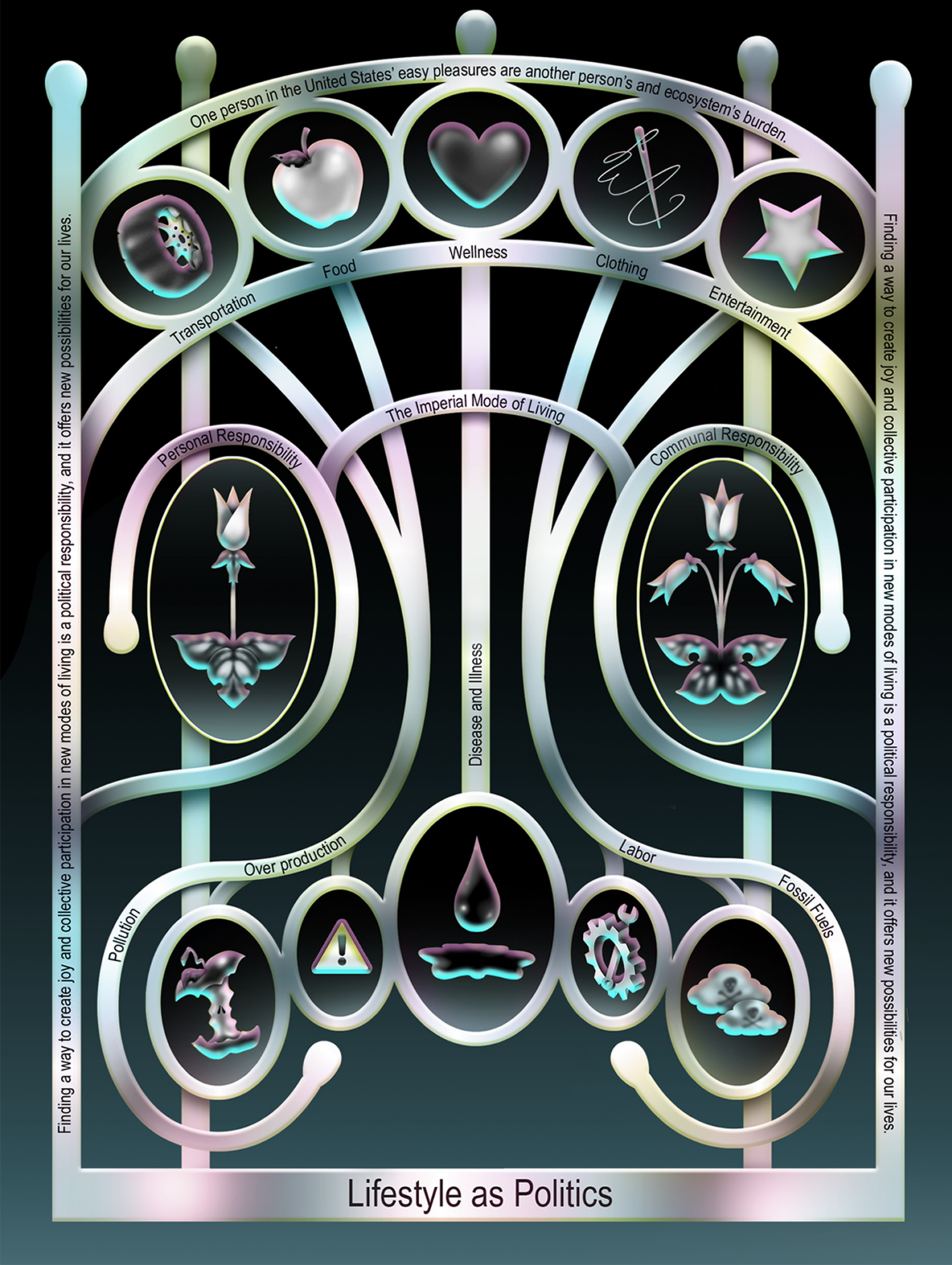

In the past 20 years, our global agricultural model has accelerated climate emissions, accounting for 72% of all surface and groundwater withdrawals and 23% of global emissions. Excessive fertilizer use, overgrazing, and livestock have contributed to soil erosion, deforestation, and soil compaction. And to make matters even worse, the soil health of 13% of global soil, including 34% of agricultural land, has been degraded. Many institutions are embracing the current trend towards incentivizing farmers into employing regenerative techniques in exchange for carbon credits to convert their lands into carbon sinks. And while regenerative practices such as no till, biodiversity, and crop rotation were championed by indigenous communities over the past 40,000 years, indigenous expertise is still absent from the climate conversation.

The first time I reached my hand down into the soil at Spirit Farm, I thought I was running it through chocolate cake. The rich, dark matter had been remediated through a variety of methods, including nutrient dense compost, patience, and working with the land. Spirit Farm is not just focused on healing the soil itself, but employing ancient ancestral technologies, such as water harvesting through swales and berms, which allow for the redirection and productive use of rainfall. The team also uses agroforestry, the deliberate planting and maintenance of trees in order to develop a microclimate that protects crops against extremes, intercropping, and crop rotation, which is designed to preserve the productive capacity of the soil, minimize pests and diseases, reduce chemical use, and manage nutrient density for maximum yield. Intercropping creates biodiversity, attracting a variety of beneficial and predatory insects to minimize pests and increase soil organic matter, suppress weed growth, and purify the soil health.

By reentering the relationship with the land through an understanding of the system being interconnected, not extractive, James Skeet honors his ancestors’ perspectives. “What’s happened with colonization all over the world is a break with reciprocity. Unlike the ancient indigenous approach to a bartering system, capitalism focuses on a small pool dominating and capturing a market to resell their products to a larger community.”

These ancient technologies not only introduced innovation, but focused on community first. The Incan Moray or ‘Muray’ in the Quechua language, for example, was a terrace system that included different kinds of soil from across the Incan empire. The terracing was so complex that there was a 59°F temperature difference between the central depression and the highest terraces at the edges, allowing for precise climate conditions and rich soil ecology. Archeologists believe that it also served as an agricultural testing station so that indigenous agronomists could experiment with a variety of crops to ensure that their community was well fed. “Everybody was always getting a nutrient level that they needed throughout the winter season or in scarcity.”

So how do we re-engage these ancient solutions in our modern world? For Skeet, not only has healing the land required great patience, but a mindset shift that he describes as moving from “the head and into the heart.” After walking the tilled, dry red clay lands on the property years ago, Skeet noticed the dominant presence of invasive weeds such as Russian thistle and bullhead. “We started to ask ourselves: how do we approach living in a sacred manner? Do we go in and kill the weeds, or ask them, “Why are you here?” And when we began to ask those questions, we found interesting results.” These succession plants, or so called “weeds,” had higher nutrient levels than the annual crops that they were growing at the time. “Our people, the Navajos, knew and understood the value of wild plants from being trans-nomadic people. A lot of medicine men and women understood the critical relationship of reciprocity between the land and the plants and what they can do.”

To discuss climate solutions means to move away from the notion of “carbon credits” because credit is a continuation of banking, an economic system that’s about transactions rather than communal relationships.

The Skeets knew that in order to amend things, they needed to work towards a higher level of biodiversity to create a heat sink to lower scorching temperatures. “The microbes create the medicine and help the soil heal and break down organic matter. We started communicating with the soil. And as we did that, we started to understand the language of the plants. And in that understanding, we realized how detrimental we can be. Colonization has had a really rough rub against us. The soil itself is starting to live, producing and providing great nutrient levels in our food that we’ve tested, too.”

The microbial sponge that’s held on the land around Spirit Farm creates mini cycles that capture water torrents that feed into maintaining soil health. By creating the microsponge that’s in the soil, it creates a hydrome that allows for water systems to come in torrents. “I wish we could do that on a much larger and broader scale, but I think we are hampered by capitalism with things like counting carbon credits, monocropping, and the commoditization of foods.”

Skeet believes that the concept of carbon credits is a naive perspective on climate solutions. “Within the framework of capitalism, it is always around the idea of introducing technology, and somebody monopolizing this technology that they will then sell to us. Restoring land has always worked for indigenous people.” The opportunity is for contemporary science and indigenous science to work together. “It shouldn’t be two separate charges that repel each other. The question climate scientists should be asking indigenous communities is: ‘Can you explain more about what you have done in 40,000 years?’ Instead of going to the tech community and asking ‘What’s the latest science technology and how can we exploit that?’”

Integrating indigenous wisdom into systems thinking requires centering indigenous voices at the forefront of climate solutions. “To discuss climate solutions means to move away from the notion of “carbon credits” because credit is a continuation of banking, an economic system that’s about transactions rather than communal relationships. We end up depriving the Earth to where we’re going to shorten our whole human existence in just a couple hundred of years when it’s taken eons for the fungi and the bacteria and all of these natural systems to develop into different, complex layers. And when your land has been stolen, mined, and extracted for things like coal and silver, your worldview is totally different from someone who is coming in with a business that’s involved in this exploitation.”