In 2017, the print edition of MOLD Magazine was launched in response to a UN report detailing an impending global food crisis. The report, which predicted that by 2030 there would be more people on the planet than our food systems had the capacity to feed, provided a lens of urgency through which to think critically about the future of food and design. Over the past five years, the publication has expanded coverage to include topics such as community-based food systems, alternative ways of eating, and regenerative agriculture, asking what role design can play in all of these fields. This solstice season, MOLD is turning our focus toward a more resilient local food ecology by launching Field Meridians, a new arts and design organization from the MOLD family dedicated to food sovereignty in our own community of Crown Heights, Brooklyn.

As we enter a new phase of MOLD, we are starting a new series that once again places food and design in conversation with policy. Earlier this year, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, released its sixth report, a damning diagnosis of the irreversibility of many of climate change’s current impacts as well as a warning that it could get much worse if greater efforts are not taken to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Centered around the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 43% by 2030 in order to limit warming to around 1.5℃, the report includes recommendations to address our current unsustainable energy and land use, lifestyles and patterns of consumption and production. In this editorial series we’ve matched critics, food writers, scientists, and designers with specific strategies proposed within the report in hopes of creating a generative site to explore how design can and needs to be employed in our shared climate future.

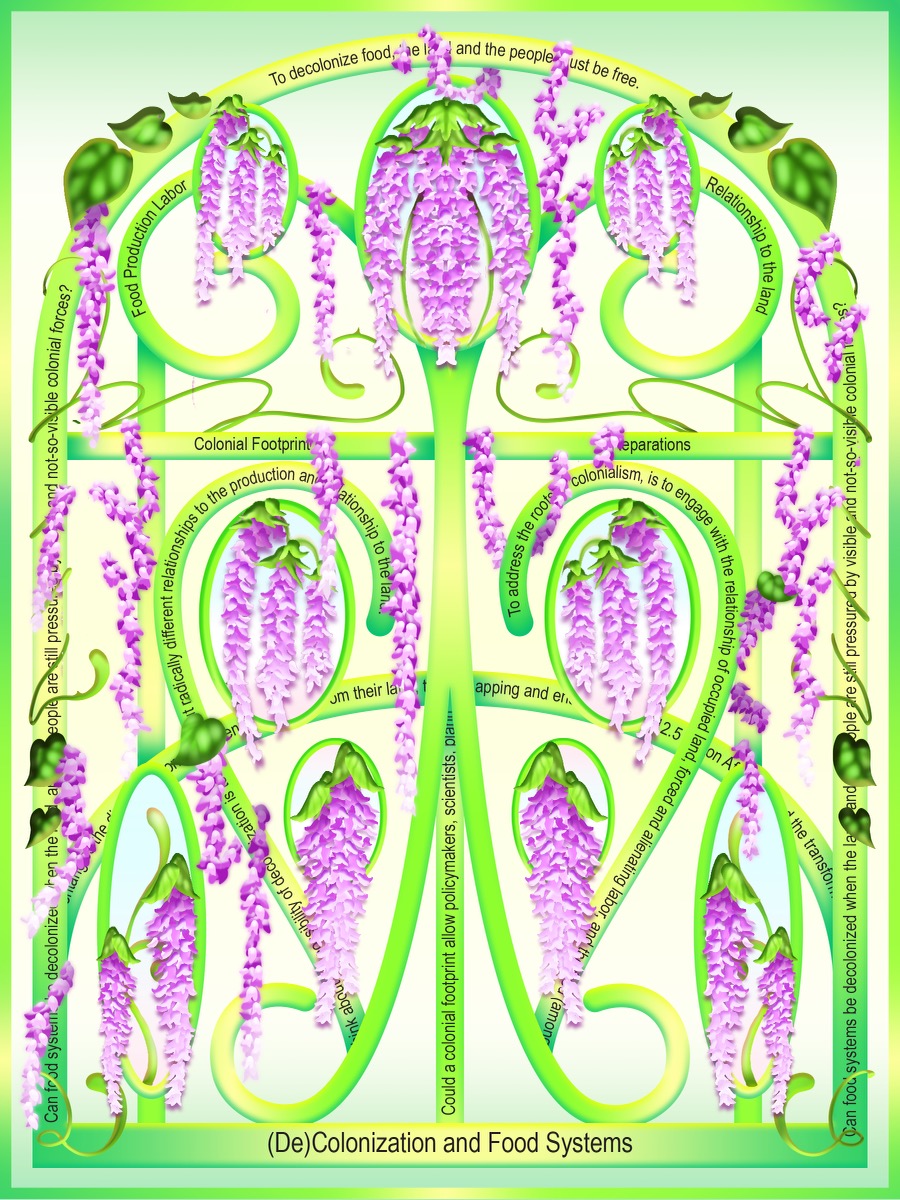

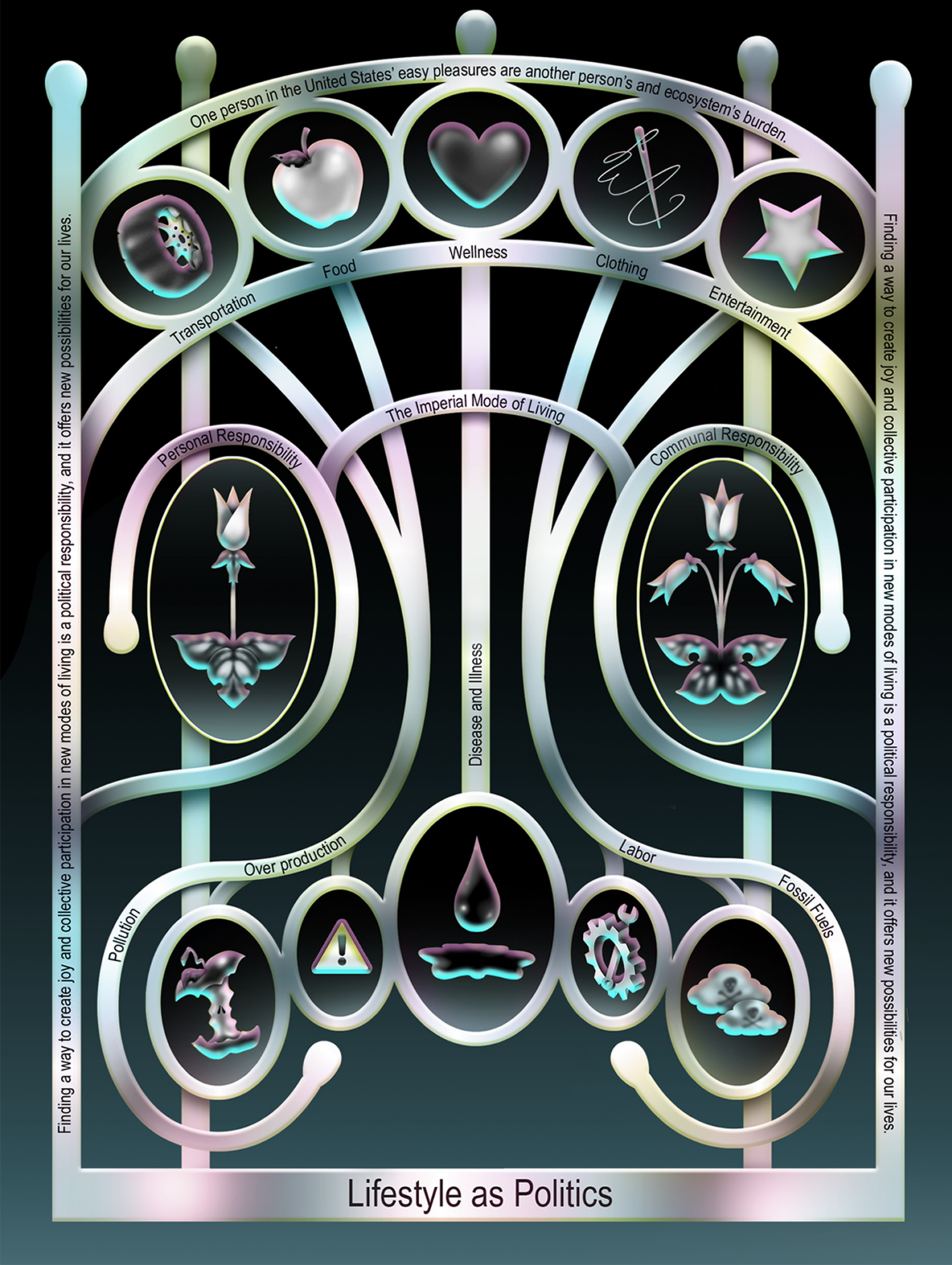

Food and culture critic Alicia Kennedy kicks off the series by responding to the IPCC report’s call for collective social change towards less resource intensive lifestyles. In this piece, Alicia challenges the aspirational consumption habits sold by popular lifestyle media and considers how restriction can be redesigned to cultivate a more nourishing way of life. Biologist Christina Agapakis mines the tensions of sustaining environmentally damaging agricultural practices, particularly the use of nitrogen fertilizers in big agriculture, to produce enough food to feed the world’s population. She delves into the work of her fellow scientists at Ginkgo Bioworks who are developing new technologies that could reduce agriculture’s reliance on fossil fuels. Food writer and editor Helen Hollyman also speaks with Spirit Farms about regenerative farming practices that combine indigenous ways of knowing with systems thinking, examining the shortcomings of contemporary green solutions such as the carbon credit system. To close out the series, WAI Architecture Think Tank imagines how design can be used as a tool to shape a decolonial food system in response to the report’s first time naming colonization as a driver of climate change.

When reading this year’s IPCC report, it becomes clear that within our current climate future the only certainty we have is change. While this in itself is enough to send one spinning into a spiral of climate nihilism, I am reminded of another document on change, one that has been fundamental to MOLD, Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower. Butler’s prescient science fiction novel opens with the lines, “All that you touch/ You Change. / All that you Change / Changes you. / The only lasting truth / is Change. / God / is Change.” Written through the eyes of Butler’s protagonist, Olamina, who navigates a familiar landscape of drought and fire in the not-so-distant future, this tenet is presented not as a call to religion, but rather as an invitation to make a home within change, to take action in spite of the paralysis of uncertainty. While policy is just one arm for enacting change, through this series we turn to our community as well as to our collective future and ask, how can we shape change?

With hope and gratitude,

Isabel