A friend recently said to me that she is ok with lifestyle journalism making people uncomfortable. In light of how our world is raging with injustice, climactic and otherwise, I couldn’t agree more. As a food writer, I think lifestyle media, so long siloed away from the dirty business of politics, needs to engage with the realities of the world.

Climate justice is a main concern for me, as I live in Puerto Rico, where the effects of 2017’s category five Hurricane Maria still linger and every year a new hurricane season looms. There are plenty of reasons for lifestyle media to engage with the reality of racial, gender, and labor injustice that all intersect with climate change and have very real implications for how, especially, to eat.

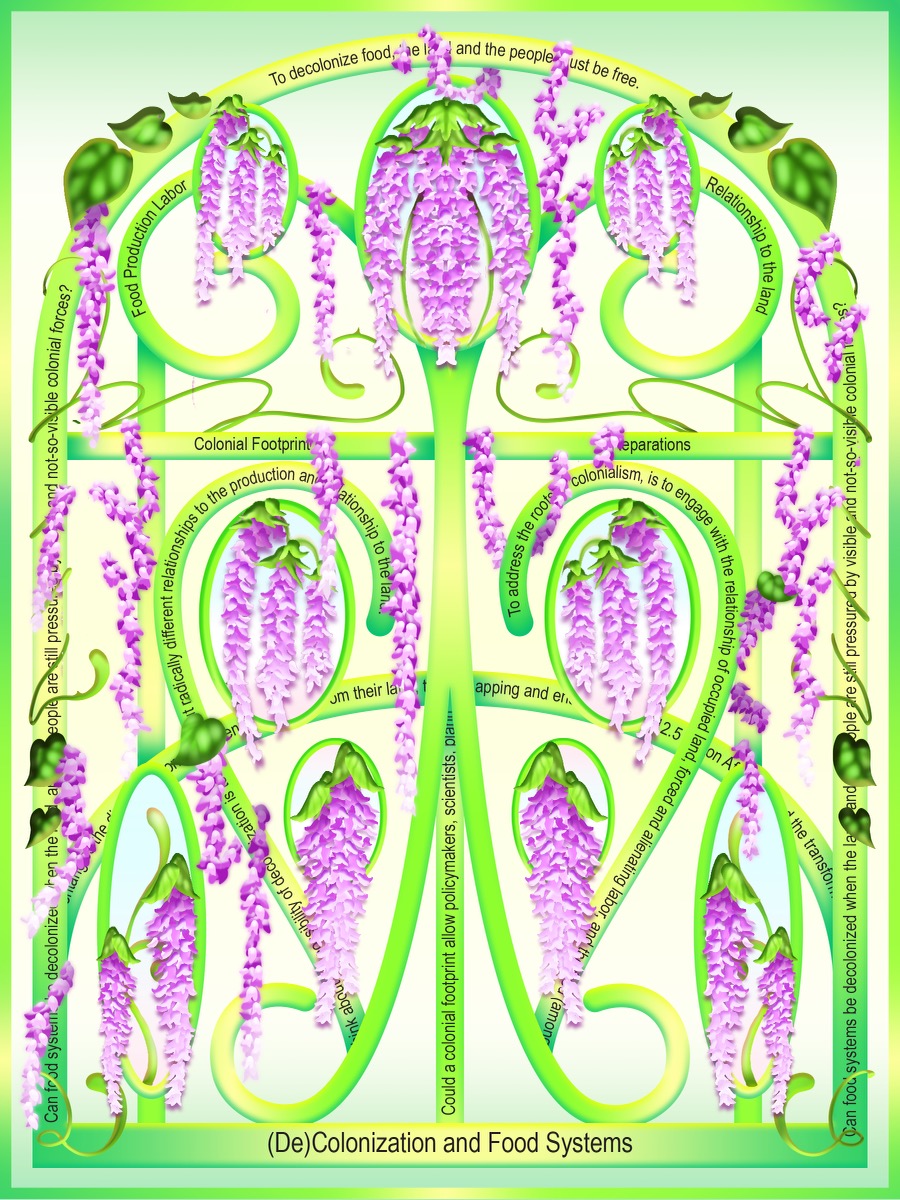

Though it’s become common to repeat the refrain that “100 companies are responsible for 71 percent of greenhouse gas emissions,” the study from which that statistic emerged focused only on fossil fuels; and while incredibly significant, it’s been watered down to suggest that there can be no worthwhile change on an individual scale or in other sectors. With food, our consumption patterns are inextricably tied with larger environmental and labor considerations. Currently, the global food system accounts for nearly a third of greenhouse gas emissions, and land use for livestock production has been a devastating force of deforestation, using up 80 percent of global farmland to provide fewer than 20 percent of the calories consumed globally. As of 2020, the food system of the United States accounted for 19.7 million full- and part-time jobs. Meatpacking companies lied at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic about a meat shortage in order to force people back to work without the proper protective conditions, leading to 269 deaths. Earlier this year, fast food and farmworkers marched in Florida for better conditions. The federal minimum wage in the U.S. has stayed stagnant at $7.25 per hour despite intense inflation.

When we say that changes only have to occur on the level of big policy and systems, we leave out the significance of public participation and the fact that how we each live our lives is part of a greater whole.

As our day-to-day lives become so encumbered by expensive necessities, housing insecurity, and looming natural disasters, the question I consistently ask is: Where is lifestyle media? It’s pondering whether burger rankings are still important; it’s accepting defeat and painting a picture of the future of food that relies on lab meat fantasies. Changing diets, though, is a crucial climate change mitigation strategy. This means changing our lifestyles: how we live them, of course, but also how we write about them and how we share them.

Recipes, in particular, could be written in ways that push people toward different understandings of access, regionalism, and seasonality. They can force a reckoning between the false universality of the American supermarket and one’s actual regional food system. But that’s only if they’re written in a way that challenges dependence upon the animal products and imported products that are known to be ecologically destructive. Rather than think of this as a restriction, it can open up possibilities for variations.

Consumption as we know it, based on the endless growth that capitalism demands, attempts to abolish alternate possibilities for regionalism and new ways of living. While the crisis of climate change has undoubtedly been caused by fossil fuel companies, it is also the responsibility of those living especially in the United States and other rich nations to change our lifestyles to fit in with the environment’s clear demands for us to tread more lightly. And it’s ever more important for those who have economic ability and cultural capital to model behaviors that make treading lightly seem easy and desirable, to show that what has been proffered as “restriction” actually houses possibility for pleasure and connection, as well as a foundation for bigger change.

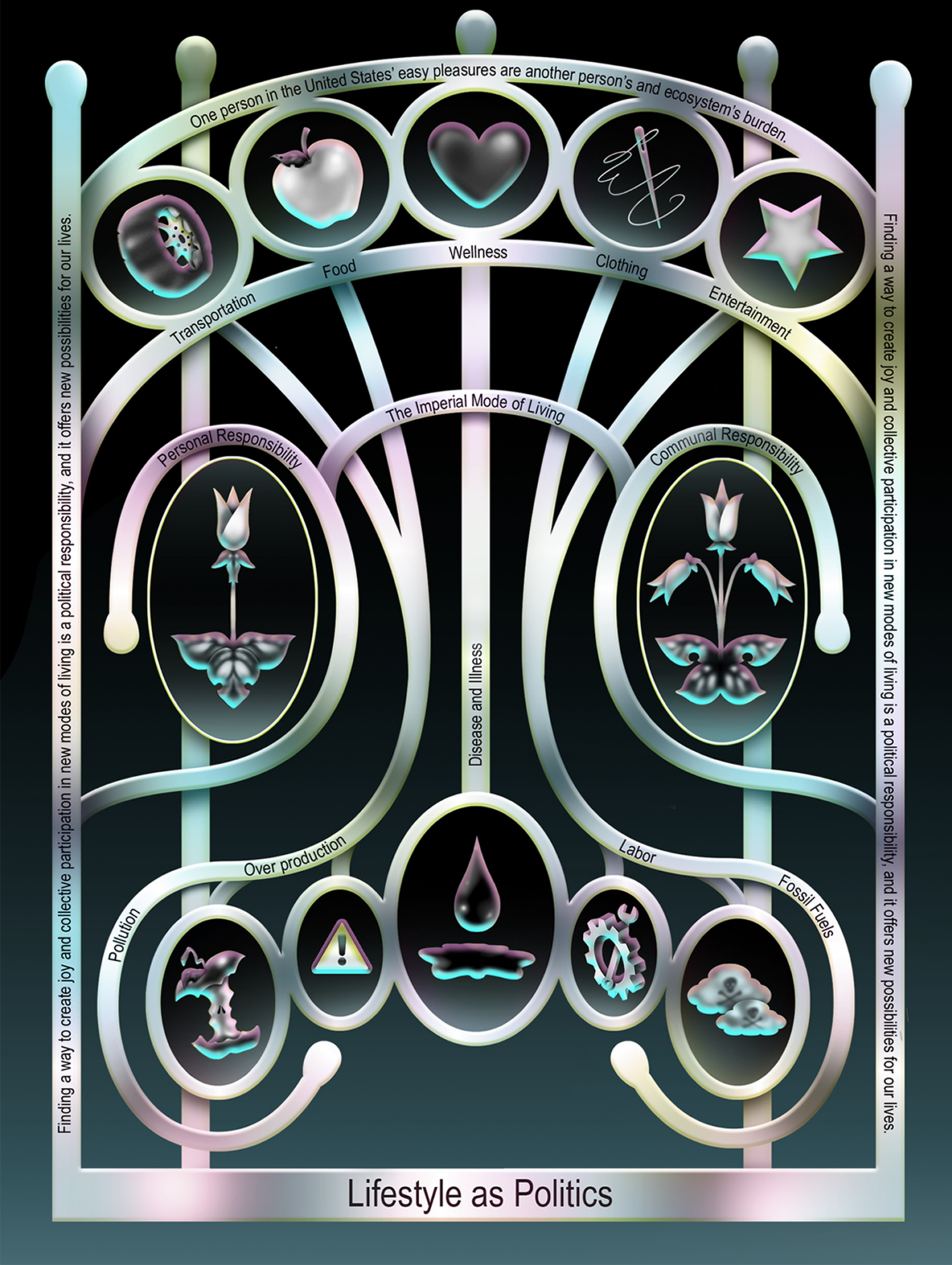

Chafing at the idea of personal responsibility here is understandable, but lifestyle choices have ripple effects. A fast fashion dress purchase might seem like a reasonable way to dress nicely, cheaply, yet the person who sewed it across the globe is poorly paid and treated, and most of the overproduction of these companies ends up polluting other poorer nations. Demand for one kind of banana, a convenient and cheap supermarket snack, pollutes growing nations and pesticides poison farmworkers. One person in the United States’ easy pleasures are another person’s and ecosystem’s burden.

This is what writers Markus Wissen and Ulrich Brand have called “the imperial mode of living.” Their book of the same name breaks down “how normality is produced precisely by masking the destruction in which it is rooted,” and this sense of normality experienced by people in the Global North as well as increasingly in some increasingly economically powerful nations understood as part of the Global South, is imperialist in nature1. Climate change is one crisis that is encroaching upon that sense of normality, and continuing to live in an unchanged manner dependent on cheap goods made elsewhere and fossil fuel consumption seems to be more and more nihilist in nature. When does a cheap dress or cheap food become worth more than the continued existence of the planet? When will normality shift to encompass the well-being of everyone? These are questions of lifestyle, cultural norms, and collective change, which also need to become questions of lifestyle media.

- 1. The Imperial Mode of Living: Everyday Life and the Ecological Crisis of Capitalism, Brand and Wissen, 2021.

Normality is produced precisely by masking the destruction in which it is rooted

In the United Nations’ IPCC most recent climate change mitigation report, the word “lifestyle” appears 193 times. The authors write, “The acceptability of collective social change over a longer term towards less resource intensive lifestyles, however, depends on the social mandate for change. This mandate can be built through public participation, discussion and debate, to produce recommendations that inform policymaking.”

When we say that changes only have to occur on the level of big policy and systems, we leave out the significance of public participation and the fact that how we each live our lives is part of a greater whole. While that would be fantastic, it feels more and more impossible without “collective social change”; these changes can occur through shifting norms and habits that will thus influence broader policy. “Shifts in development pathways result from both sustained political interventions and bottom-up changes in public opinion,” the report says. “Collective action by individuals as part of social movements or lifestyle changes underpins system change.” People decided to bring their own reusable bags to supermarkets, for example, and now states and municipalities have instituted single-use plastic bag bans.

When it comes to food consumption, an important aspect of changing lifestyle is increasing the desirability of plant-based diets specifically. This requires normalization, and perhaps a bit of discomfort. In what we call “lifestyle media,” causing discomfort has always been a big no-no—opening up a food magazine to find anything about habit-changing for climate change might happen once per year, while steaks are on offer the other eleven months. Even vegetarian recipes are promoted in a special section, while lamb and chicken are the norm for the main.

How we live our lives, how we choose to move around the world and consume, has effects: Maybe we just feel slightly better, maybe we influence change in our immediate communities, maybe that change in our communities causes local policy change and eventual regulation of deeply destructive industries. The imperial mode in which people in the Global North consume will change, whether because of climate change and extreme weather events or as a way to stop it. Finding a way to create joy and collective participation in new modes of living is a political responsibility, and it offers new possibilities for our lives.

- 1. The Imperial Mode of Living: Everyday Life and the Ecological Crisis of Capitalism, Brand and Wissen, 2021.