This piece is a part of our series Metabolic Systems which looks into the cycles that underpin our cultures of consumption, from decay to digestion.

Not long ago I dreamt that I was in a supermarket, scouting out waffles for a family brunch. What I found there instead was my own grandfather, his stout legs fastened to a pair of stilts. Before I could catch him, he began to fall over, teetering into a shelf of packaged food. I helped him onto his feet and walked him out of the store, throwing the broken stilts into the back of the car. Ellaam kilinchu poochu. “It’s all torn up,” my grandfather said mournfully in Tamil. I couldn’t tell if he was talking about the stilts, the failed plans for brunch, or the condition of his own body. Nevertheless, a melancholy mood of decay had settled over everything.

Staying up, falling down—the pathos of a mortal life is reflected most simply in the determination to remain upright in the face of natural forces of decay. My grandfather eventually ceded this struggle about a decade ago, after nearly a full century of life. For him, as with most of us, living with the reality of coming undone was an effort that took the support of a network of family and kin. And this was care that extended to his body and being, but also to the space my grandfather occupied day and night for most of his final years: the house in the south Indian city of Madurai that he and my grandmother built in the 1980’s, a place that was lovingly maintained by one of their sons and daughters-in-law for many decades thereafter.

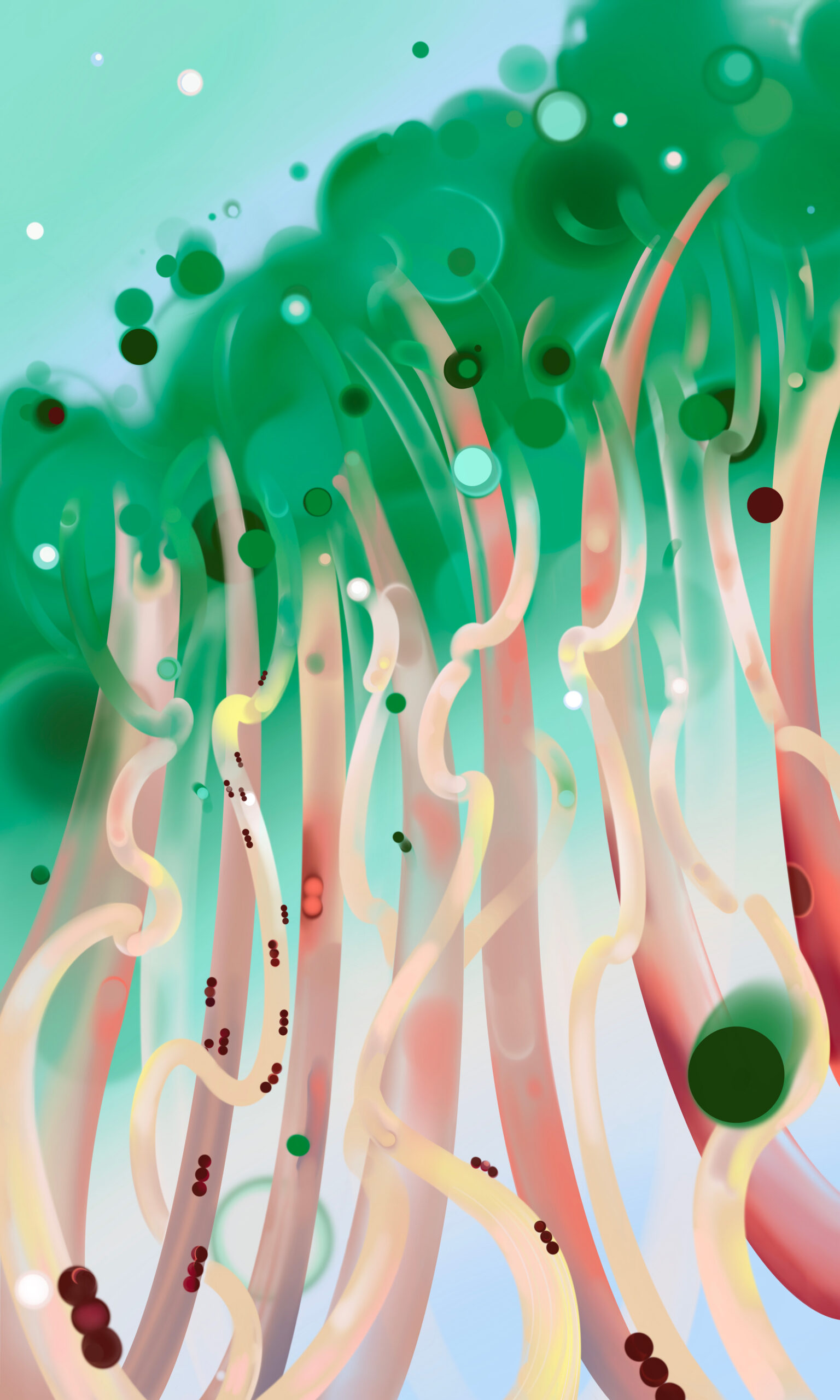

The relationships that mediate experiences of decay are widely attested in the literature of Tamil Nadu, the part of India from which my family hails. Take, for example, this Tamil verse from the early medieval ethical work Naladiyar, where the support lent by one generation to another is imagined through the succession of aerial roots that keep a banyan tree aloft, even after the disintegration of its original trunk:

Like the hanging roots that hold like pillars

the banyan tree eaten away by ants,

the weakness of an aging father

will be covered by his son.

The verse represents the challenge of decay in material and structural terms, even as a matter of architectural form. It invites us to imagine what structures of support could ensure the continuity of life in the face of rot and ruin. This problem has even more urgency in our present time, defined by a widespread sense of things coming radically undone. As so much seems to be falling apart at our feet, the task of finding structures and forms to keep life going looms ahead. What might spaces that acknowledge our vulnerability to decay look like? Can we learn to face such loss in a spirit of reparation and repair, rather than denial or refusal? What answers to these puzzles might we find in the architecture of our built worlds?

The Life and Death of Buildings

The image of my grandfather gingerly navigating a long pair of stilts was a strange and unsettling one. I realized, when I woke up, that it must have had something to do with the book that I’d been reading each night that week, Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. The book is a trove of fantastical urban architectures, some of which feature cities and buildings on towering stilts. As it happened, that week I was also visiting the city that Calvino modeled so many of his imagined places upon, the city of Venice.

A place whose ornate structures have long been undone by the corrosive force of seawater and salt, Venice is a good place to reflect on what it means for architecture to make peace with decay. When I described my interests in rot and ruin in a conversation there, a scholar quipped wryly in response, “Venice has been decaying forever.” We were speaking that afternoon within the cavernous interior of the Chiesa di San Lorenzo, a 16th-century church that has been transformed into a venue for environmental exhibitions. For an installation called Lunar Ensemble for Uprising Seas, artists Petrit Halilaj and Álvaro Urbano had filled the space with delicate marine creatures fashioned from thin metal. That evening, musicians would wield these silvery figures as instruments, filling the vault with ghostly sounds to suggest that the building was already undersea, a possible reality that we had to accept.

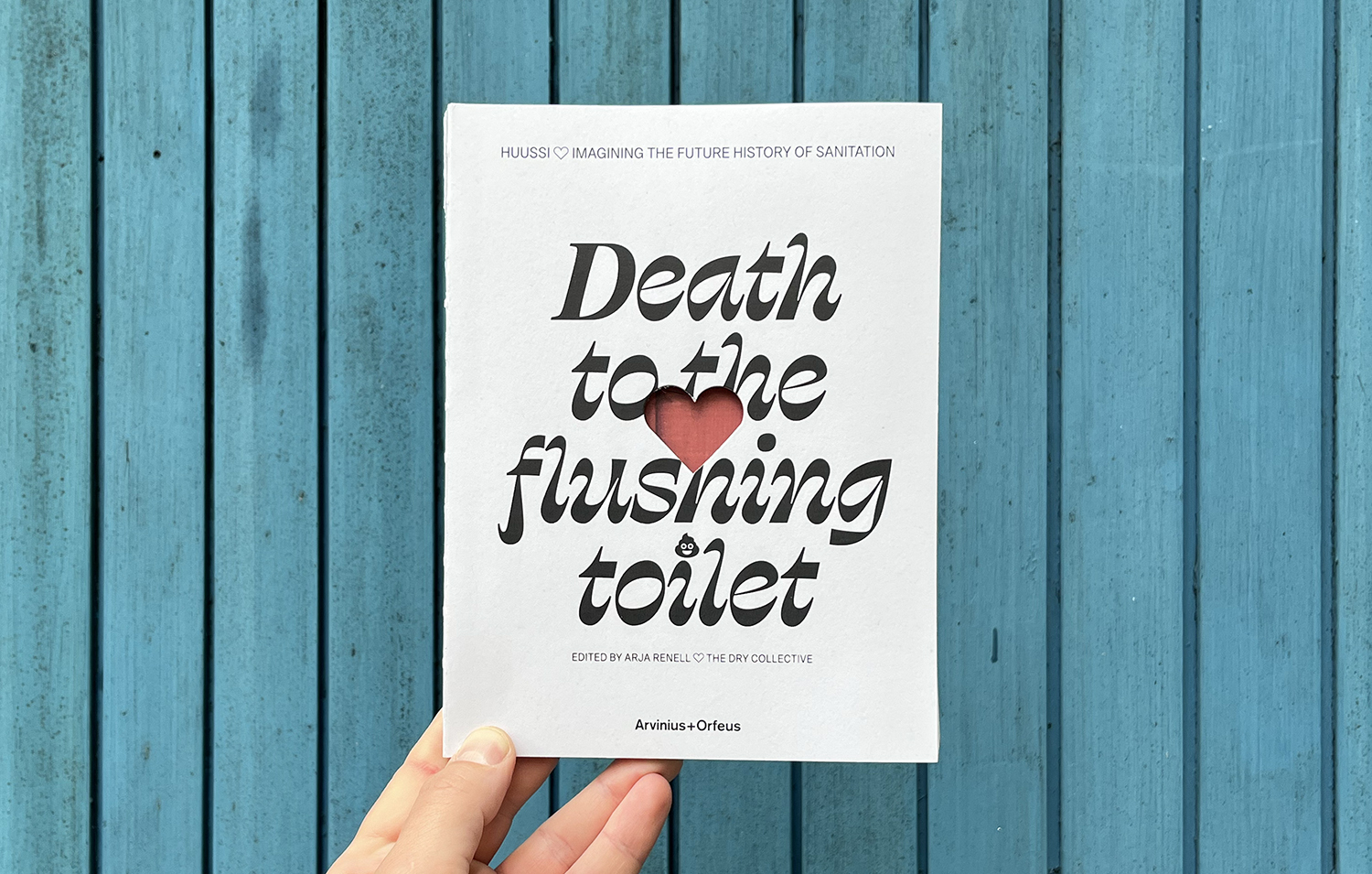

I had come to Venice for the 2023 Architecture Biennale, staged with the theme “The Laboratory of the Future.” A walk among the pavilions set up by participating countries was a tour through a diversity of aspirations that could take shape in the face of impending planetary loss. A Danish exhibition described urban strategies of adaptation and planned retreat to accommodate the influx of rising seas. An installation in the register of post-apocalyptic fiction produced by the Urban Terrains Lab from Korea suggested that “ruin is the future of our city, and the future city is ruin itself.” A team of designers called the Dry Collective conceived the future in more upbeat terms, proposing Finnish huussi or dry composting toilets as “the future history of sanitation.”

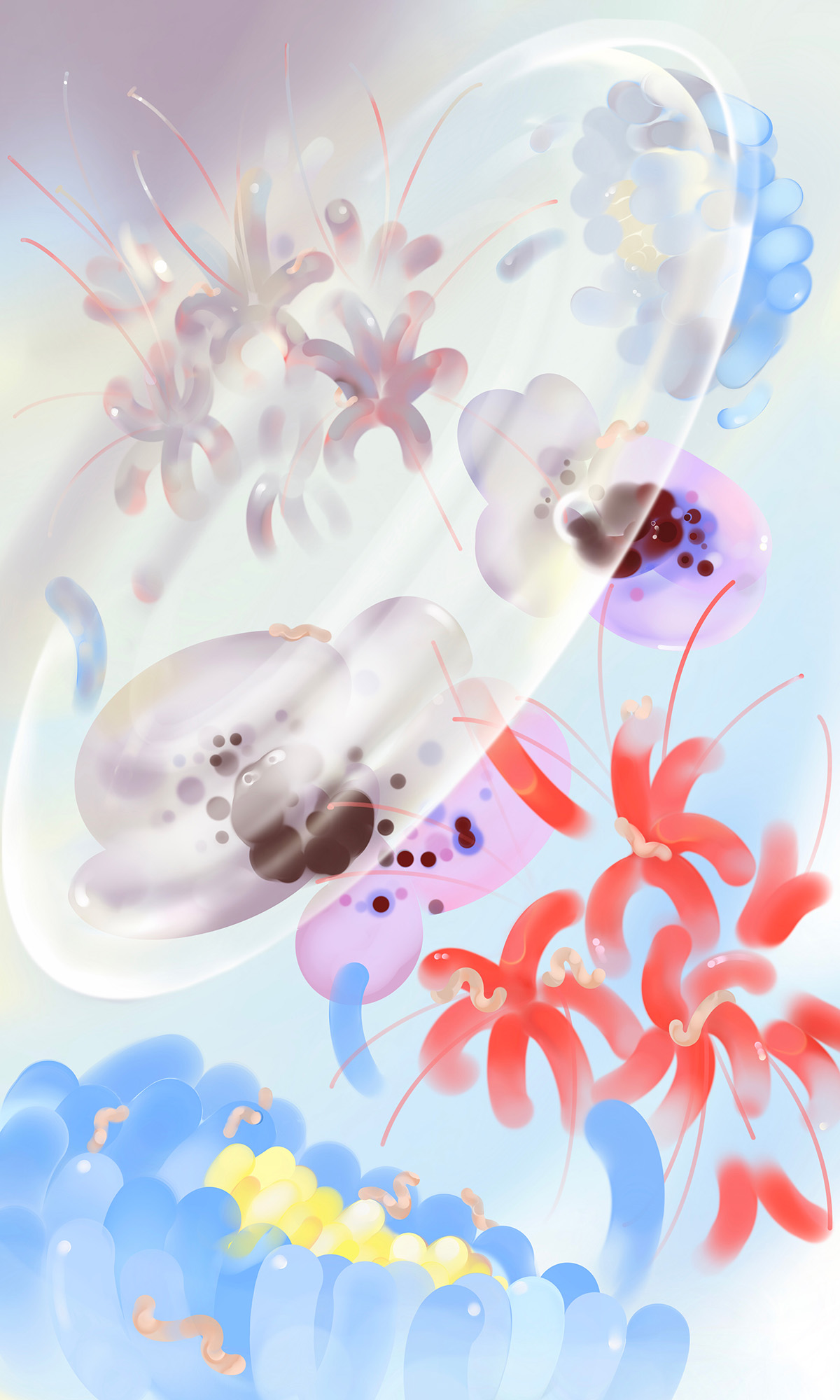

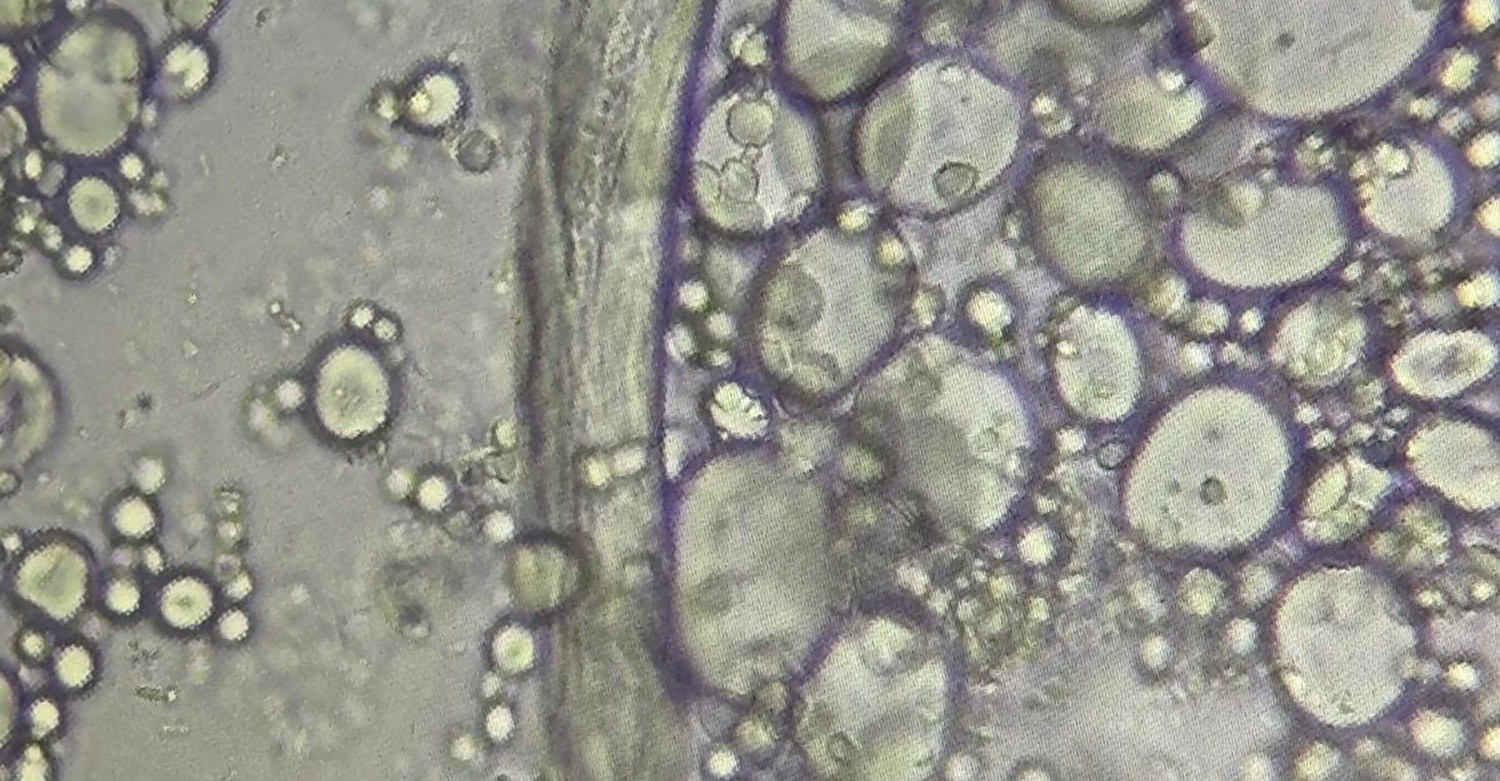

What could it mean for contemporary architecture to work more intentionally and deliberately with the necessity of decomposition, and the reality of decay? The Belgian Pavilion at the Biennale invited visitors to imagine a future of Living in Mycelium, in which mushrooms had become the most basic architectural elements, sustaining houses that could generate and regenerate themselves while still retaining compostable forms that could eventually be reabsorbed into local forest landscapes. A team of architects from Turkey, meanwhile, showcased ways of working creatively with existing architectural structures in states of abandonment and decay, taking them as sites to repair and repurpose for unexpected ends. As a passage from Buildings Must Die, a book by Stephen Cairns and Jane M. Jacobs featured in the Turkish exhibition insisted, “If buildings must die, they should have a second chance to live.”

Materials of Decay

Like that of those who occupy them, there is a life and death to buildings, with their own interwoven trajectories of growth and decay. Concrete, steel, and glass, the signature materials of modern construction, lend architectural structures a feeling of permanence, the ability to defy the ebb and flow of nature. But these are also materials responsible for the enormous carbon footprint of the construction sector, and its profound effect on the changing climate. These materials are also resources extracted from far-flung places, making every gleaming new building a symbol of international networks of control and exploitation. The comfort of those who live within such structures comes with the degradation of countless places beyond, the pervasive and unseen rottenness of the contemporary economic order.

The 2023 Venice Biennale of Architecture was developed with these concerns in mind, taking two necessities—decarbonization and decolonization—as its central objectives. Importantly, African and African diasporic studios were responsible for more than half of the work showcased in the exhibition. As the Biennale’s curator, Ghanaian-Scottish architect Leslie Lokko put it, “The spotlight has fallen on Africa and the African diaspora… What do we wish to say? How will what we say change anything?” One message that these works conveyed emphatically was the possibility of finding a way to thrive in the face of deep legacies of loss and damage. As the Nigerian architect Tosin Oshinowo suggested in the Biennale’s catalogue, “Brought to the brink of collapse by inherited or adopted Western or Global North planning principles that simply didn’t work, African cities have slowly—somehow—managed to grow and thrive, largely because of ingenuity born out of these conditions of scarcity.”

Take, for example, the voluminous forms developed by the studio of Ghanaian artist Serge Attukwei Clottey, like the yellow fabric stitched together from thousands of pieces of discarded plastic water gallons and suspended like a tapestry of waste above the shimmering blue of a Venetian canal. The work forced one to confront the afterlife of modern materials, and the value they may assume unexpectedly in places with a more inventive sense of available resources. A similar sensibility was embodied in Parliament of Ghosts, an installation by another Ghanaian artist, Ibrahim Mahama. Rows of empty chairs and cabinets stuffed with rotting paper records and material scraps gestured toward the melancholy legacy of modernist interventions in West Africa, provoking the question of how to live in the wake of their failed visions.

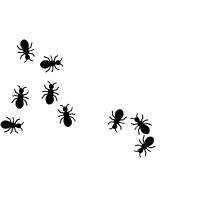

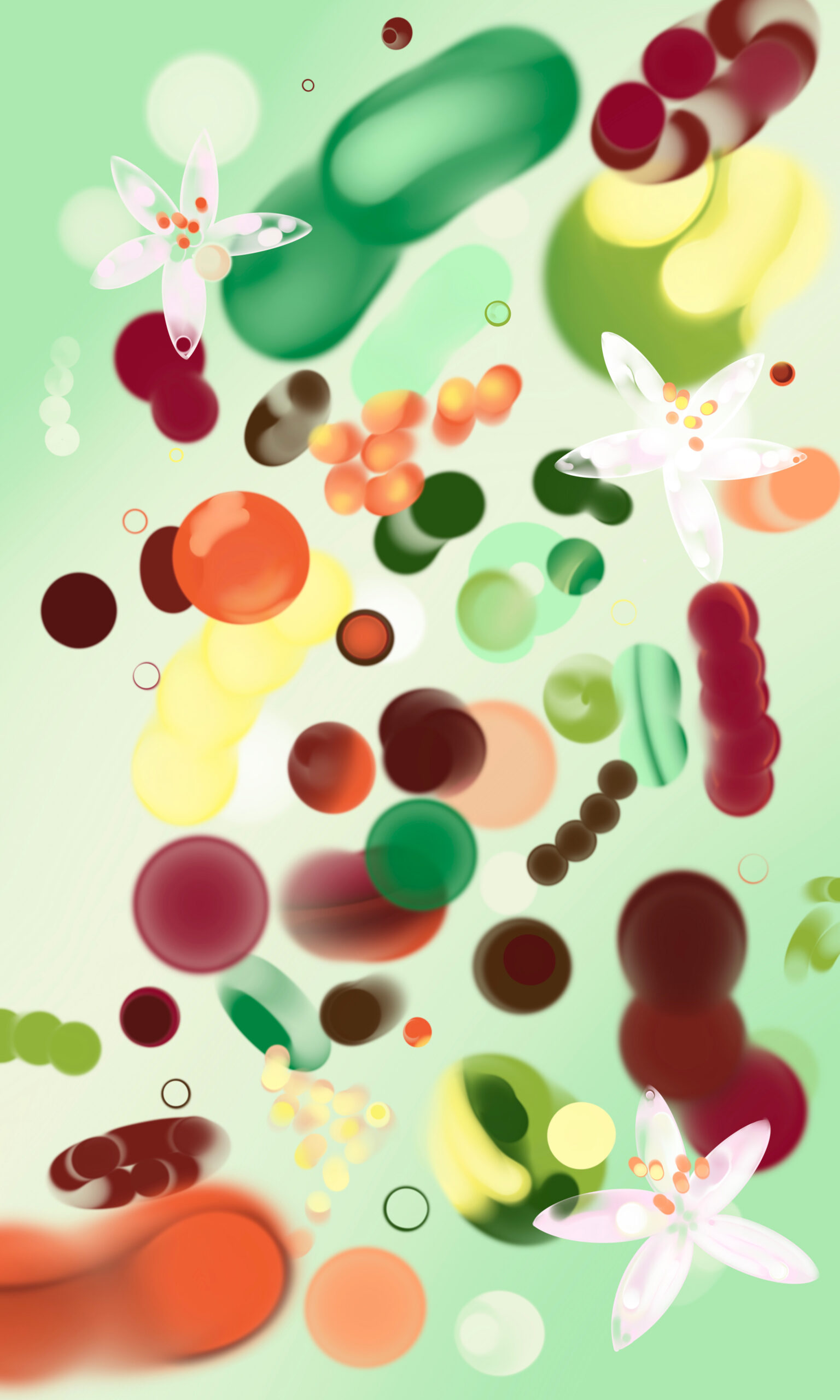

An installation staged by the Pritzker Prize-winning Burkinabe architect Francis Kéré began with this startling observation: “The entire continent of Africa is responsible for less than 4% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.” The sweeping earthen walls that composed the installation suggested the possibility of other futures anchored in more environmentally sensitive vernacular traditions, proposing an alternate future of working creatively with the organic life of natural materials. The promise of an African futurism took on a more exuberant tone in the fictional scenario envisioned by the Nigerian diasporic artist Olalekan Jeyifous. In ACE/AAP, the viewer is plunged into a 1970s world in which African environmentalists and scientists have come together to devise a space-age mode of international travel founded on the capture of energy from algal decay. The installation was staged as a departure lounge, and you could feel it as you nestled into its seats, this possibility of an exit from the givens of our time.

Practices of Repair

A few months later, I had the chance to visit Ghana myself for the first time. Symptoms of the global waste crisis were immediately evident in Accra. Beyond roadside channels choked with plastic bags and bottles, there were signs of other difficulties posed by a contemporary consumer culture founded on disposable things that refused to break down, like the glut of cheap foreign clothing and e-waste dumped on Ghana, typically from Western countries. I met many people wrestling with these challenges in creative ways, including architects. Foster Osae-Akonnor of Ghana’s Green Building Council and the Ghana Institute of Architects, for example, described some experiments he had underway. One project worked with waste materials like ash and sawdust to tackle the massive amount of energy embodied in conventional cement, while another looked at fashioning retaining walls using a matrix of discarded plastic bottles rather than concrete blocks to reduce the need for both concrete and rebar.

In one of Accra’s northern suburbs, I met Joelle Eyeson, one of the principals of a small construction studio called Hive Earth, which had catalyzed a revival of interest in rammed earth walls, which were far less energy-intensive to manufacture than concrete. I told her how captivating I had found a building of theirs that I had visited elsewhere in Accra, confessing that I could not help but hold my hand to the cool, pebbled surface of that earthen wall. Eyeson said that many people have told her the same thing, describing a more unusual form of assurance that such constructions can give in a time when so much seems to be coming apart, a deeper sense of support from the earth itself. “You can look at an earth wall for ages, and it just relaxes you,” she said.

Contemporary experiments with earthen construction in West Africa draw from centuries of such usage, though you don’t see them very often in cities like Accra. Much of the emerging urban landscape here is knitted together with concrete and steel, countless unfinished towers looming over the horizon at every turn. But it would be a mistake to take even these constructions as a straightforward mimicry of Western practices. Ghana became a hub for tropical modernist architecture in the twentieth century, and vernacular practices here continue to reflect a great deal of ingenuity and originality, especially when it comes to matters like waste and decay. The cheap wooden forms used to shape concrete slabs, for example, typically find new uses again and again even as they slowly deteriorate and decay. “Most things will go down that chain until termites eat them up and they can’t be used again,” architectural historian Kuukuwa Manful explained to me over coffee one morning in Accra.

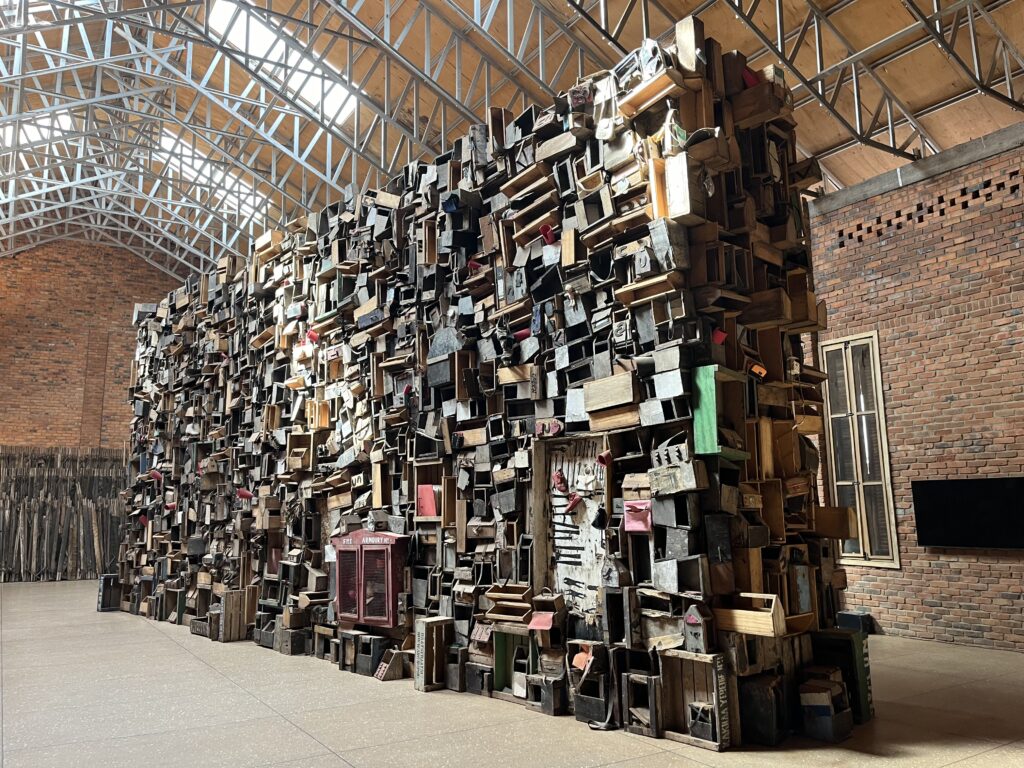

Discarded and decaying materials like these are also the foundation for the work of many of Ghana’s most prominent contemporary artists, like Ibrahim Mahama, whose base of operations in northern Ghana I had the chance to visit a few days later. On the arid savanna landscape beyond the town of Tamale, Mahama had developed a vast studio for contemporary art known as Red Clay. Showcased here were some of the works with repurposed jute bags and other industrial castoffs that had won him international acclaim, including a different version of the Parliament of Ghosts that had been installed in Venice. At the heart of one hall here was a towering monolith, architectural in form, built from hundreds of wooden shoeshine boxes of many sizes and colors that Mahama had gathered from those who practiced this trade on Ghana’s streets. As something like an archive or library of bygone ambitions, the work had a haunting and magnetic presence.

It was a blisteringly hot day, but the open halls at Red Clay let the air pass freely and gave some respite from the sun. Everything here would continue to live and evolve with the changing elements. These works were meant to archive the illusory promises of a modern world driven by commerce and colonialism, Mahama explained when we sat down to talk in an open courtyard nearby. They were also meant to help imagine a different kind of society that could yet develop, beyond the tyranny of the commodities we faced. “The aim isn’t to build something to last for eternity,” he told me, “but instead to change the relationship to the society we find ourselves in.”

Anand Pandian teaches anthropology at Johns Hopkins University. He is currently working on a new book project on decay, waste, and the crafting of ecological futures.