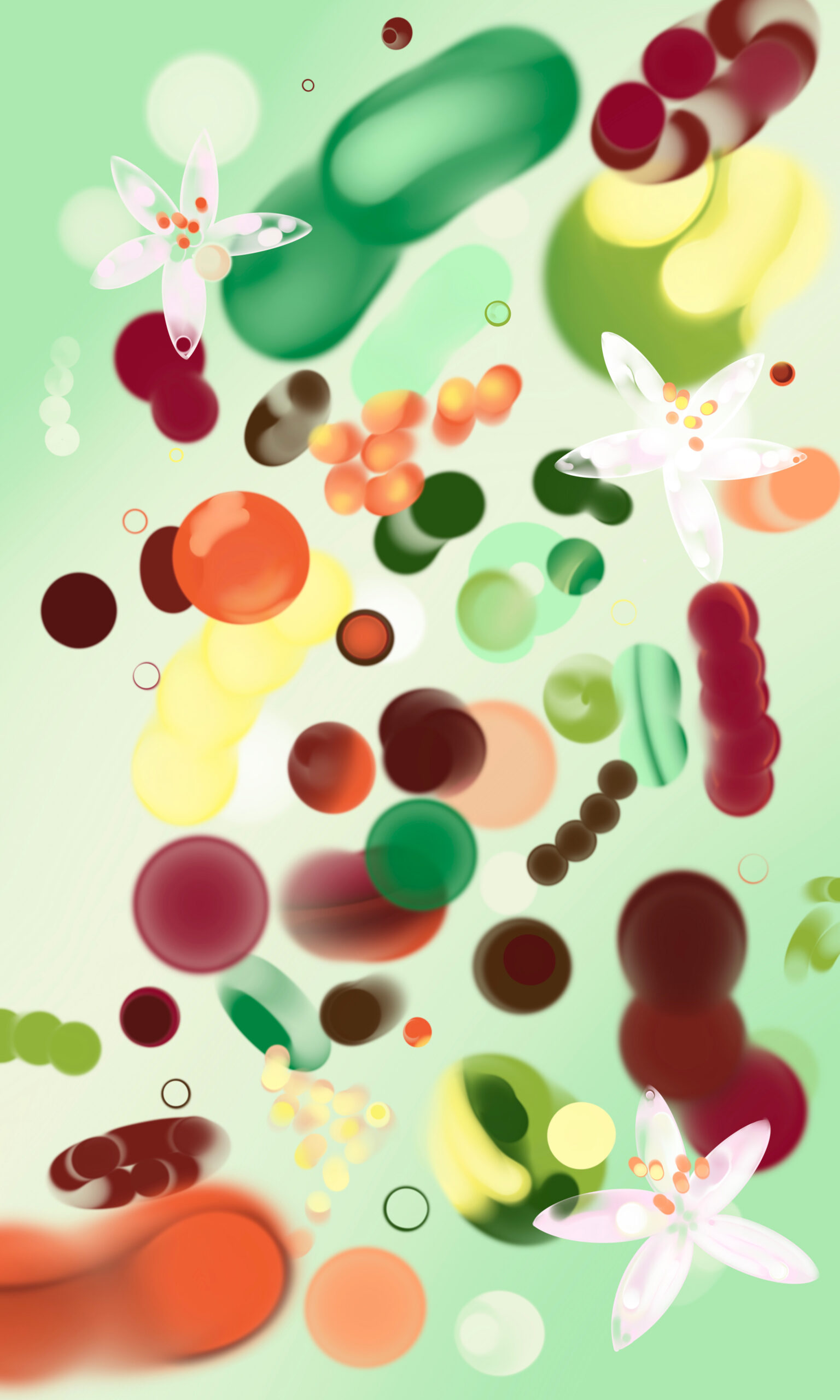

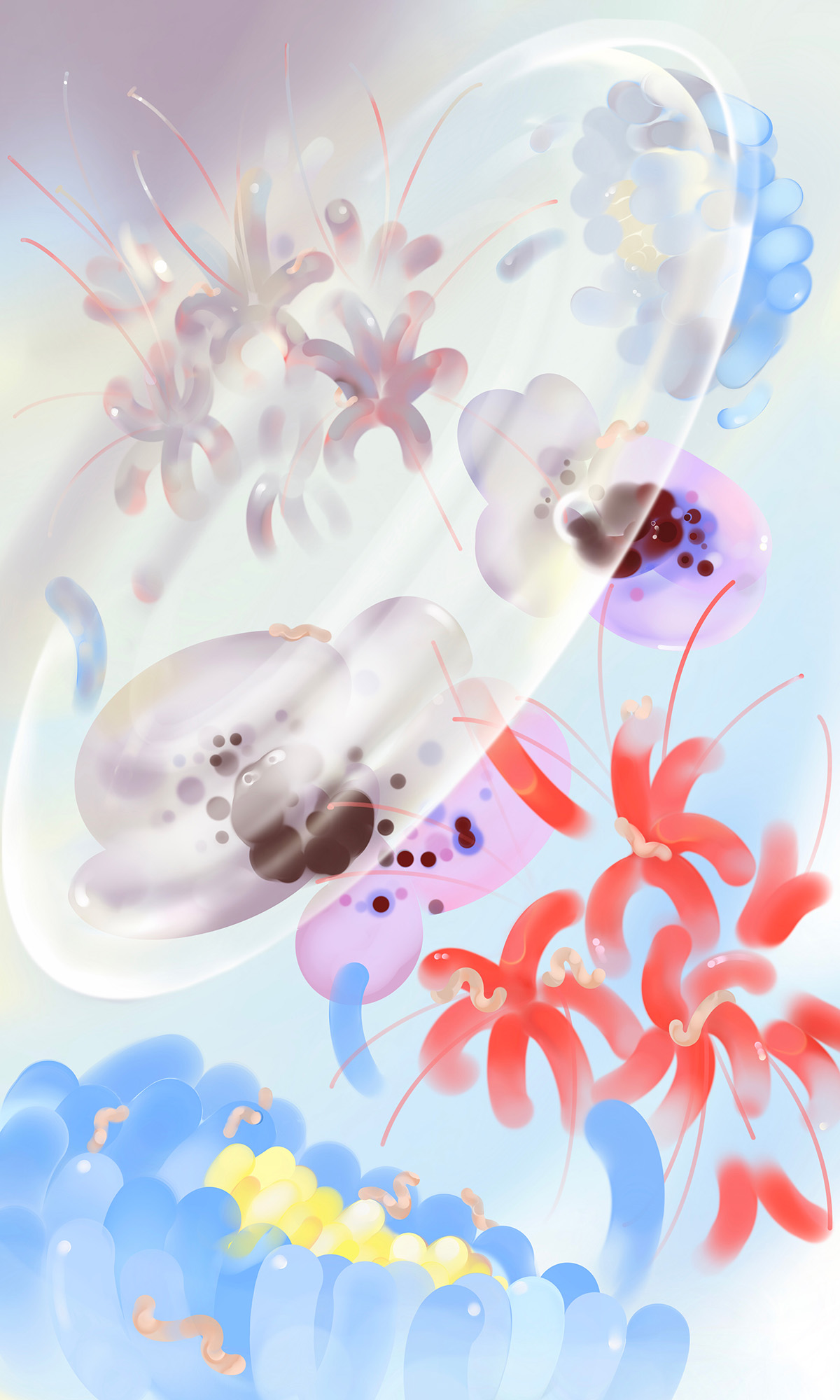

This piece is a part of our series Metabolic Systems which looks into the cycles that underpin our cultures of consumption, from decay to digestion.

In the first week of the new year, we witnessed an incomprehensible tragedy unfold before our eyes: Los Angeles was on fire. For 24 days, 14 firestorms tore through the city sparing nothing. The fire had its own logic, taking family homes in the historically black neighborhood of Altadena and leveling seaside mansions along the Pacific Palisades. 18,000 homes and structures were destroyed as the fires burned through 57,000 acres of land.

From the dystopic haze of political finger-pointing and predatory corporate interests, a simple petition emerged. It called for immediate action to address the firestorm catastrophe through Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge (TEK). The “Petition for a Climate Resilient L.A.” brought together an unlikely coalition between the artists Lauren Bon (Metabolic Studio) and Patrisse Cullors (The Center for Art and Abolition, Crenshaw Dairy Mart, Black Lives Matter); Anawakalmekak, a K-12 school that centers Native American pedagogy; and the Gabrielino-Shoshone Nation of Southern California. As the woefully deficient State (local, city, state, and federal) response to the catastrophe made clear, community preparedness at a grassroots level is the only way forward. The coalition’s call for an Indigenous-led recovery strategy that upholds traditional knowledge of the land, water and its capacity, charts a path that honors the safety net of mutual aid and hyperlocal community, while seeding a different future for the entire city of Los Angeles. The strength of the coalition emerges in this mutual vision for being in deep relationship with planetary metabolisms.

MOLD spoke with coalition members Lauren Bon, Gabrielle Crowe (vice chair and secretary of environmental sciences, Gabrielino-Shoshone Nation), Marcos Aguilar (executive director, Anawakalmekak), and Patrisse Cullors, about the vision of the coalition, its roots in ceremony and reparative justice, and the transformative ways that Indigenous stewardship of ancestral lands charts a more resilient future.

LinYee Yuan:

How did this coalition come about?

Lauren Bon:

When the fires first began, Patrisse and I spoke about the importance of holding our elected officials accountable, and specifically, that a petition to incorporate traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) into fire recovery and prevention would show solidarity through numbers. It was absolutely essential that we work with Marcos [Aguilar of Anawakalmekak], who’s helped me understand the importance of centering coalition building around consensus. We are not unilaterally talking about what TEK means from a position of authority, but rather asking the right questions of the people who can speak about TEK. He invited Gabrielle [Crowe, Gabrielino-Shoshone] to join us as she is a tribal member from this place.

LY:

What were the immediate concerns that TEK could potentially address? And how would an indigenous-led action differ from what the city is proposing?

Gabrielle Crowe:

Prior to the fires, we realized that the infrastructure in Los Angeles is not what it should be as far as disaster preparedness. And when the fires actually happened we recognized that it was a lot of volunteers—people of the city—rather than big government, that were responding to the crisis. This is not a one-off event. It is important to create something so that the community is empowered before any disasters happen—whether it’s an earthquake, flood, fire, or something else.

When twelve acres of land was rematriated back to our tribe two years ago [the Chief Ya’anna Vera Rocha Regenerative Learning Village, in partnership with Anawakalmekak], we hit the ground running and began to remediate the soil, returning the land to what it’s supposed to be. And one of the biggest ideas that has come out of this process is to build a climate resiliency hub in Los Angeles.

Right after the fires people wanted to return to their homes as soon as possible. This scared me—they want to build in the exact same way they built before. Part of the TEK and Indigenous-led climate resiliency knowledge is making sure that new builds are done so with intentionality: from material choice to spatial corridors. Even returning to cultural burns in the area, although that comes with challenges in the city of Los Angeles.

LY:

And how would a climate resiliency hub support that preparedness?

GC:

I’ve participated in a number of fellowships over the past few years, including a land rematriation fellowship, where I traveled across the state of California and as far as New Zealand. I got to witness a full spectrum of what it looks like to have land back—from people who have just gotten land back to those who have full control of the land. In Aaotearoa, the Māori have a lot of land control and I got to see what it looks like for culture, traditions, and language. They use ecotourism to fund and support their 16-24-year-old youth. The Sogorea Te’ Land Trust is using a different approach where they have small plots of land around the city in Oakland and the Bay Area and are building community gardens and storage for emergency supplies.

So beyond the emergency preparedness, we see our climate resiliency hub as an actual building and lab space that would empower our community, including students from Anawakalmekak and greater LA, to show what it looks like when you are going back to someone’s land that has been rematriated. It would be a place for research—we’re using traditional knowledge not just from thousands of years ago, but also weaving in Western science and modern technology to collect data, return the power back to the community, and benefit land use. We are not waiting on the building to do this work—we’re already doing it.

LY:

I want to highlight the learning hub as something that is open to students of all ages to be able to commune with ideas. On Anawakalmekak’s website there is this beautiful statement that “ceremony is education and education is ceremony.” Why is this critical perspective so important to bring into city planning for a climate resilient LA?

Marcos Aguilar:

It’s a complex question and we’ve thought about it for over 30 years now, as educators coming to education as student organizers. The foundation for Anawakalmekak is in the Indigenous rights movement and in the Chicano movement that established the department for Chicano Studies at UCLA. As students, we organized a hunger strike and threatened the university with death so that others wouldn’t feel the need to die internally. We’ve had to return to that core principle many years over the last two decades in Anawakalmekak.

But to prepare to die, we need to know what we’re living for, and ceremony helps guide that way. Ceremony helps communicate a sense of purpose among ourselves and with, as we say in our languages, in Nahuatl in particular, “for whom we live” or “because of whom we live.”

That act of communication, thanksgiving, relationship setting and resetting, and regenerating is what we call an English, “ceremony.” It takes place in many different ways. Part of our struggle has been to visualize that in a way that doesn’t make us even more vulnerable. It is easy to forget how recently American Indians gained the right to religious freedom in this country.1 That is a protected status for many federally recognized tribal citizens that doesn’t get extended to other Indigenous peoples like California natives that are state recognized. Non-federally recognized tribes still do not have a legal right to rematriation or repatriation of ancestors.

- 1. The American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA), which legalized traditional spirituality and ceremony, was passed by Congress in 1978.

There are existing structures, like some ecological laws in California for environmental protection. One of them is called CEQA that requires tribal consultation.2 But when a government agency administratively exempts itself from California, the tribal consultation is also exempted.

For example, San Pedro High School is situated on an extremely important, culturally sensitive site for the Gabrielino peoples.3 It was subject to a multimillion dollar modernization program where they dug up the earth and uncovered millions of fossils that were previously protected. The response from mainstream media was, “wow, we’ve found a treasure trove of fossils,” not, “we should stop.” “Maybe we should get back into tribal consultation to consider the needs of Indigenous peoples.” Besides our relationship with the Gabrielino-Shoshone nation, I’m also quite shocked to see the lack of tribal response to those types of invasions of sacredness. How much more sacred can we be when we start touching ancestors, whether they be in human or animal form, that are so old, so sensitive, and should be protected? This is happening at a massive scale across Los Angeles where the school district recently passed a $9 billion bond for school modernization, which encompasses thousands of acres of land on tribally sensitive territories.

- 2. The California Environmental Quality Act was passed in 1970 to put in place a protocol of analysis and public disclosure of environmental impact on proposed projects.

- 3. A note from Marcos: It should be stated that we’re using Gabrielino as a colonial term based on the San Gabriel mission because the complexity of Indigenous ontology goes beyond a quick introduction, but we’ll use that term for now. And it’s the term that the Gabrielino-Shoshone nation has used, as well as Tongva, and others use Kizh. It’s up to them.

But to prepare to die, we need to know what we’re living for, and ceremony helps guide that way. – Marcos Aguilar, executive director Anawakalmekak

So ceremony intersects the space between self development—as our concern for the evolving growth of the humanity of our children—and a sense of place for community. Ceremony also sets a distinction between traditional ecological knowledge as a plug and play algorithm, to thinking about indigenous science as also native law. When we understand that traditional ecological knowledge is both science and law, we understand that there are protocols to follow to be able to respect that law, to remember that law, and to teach that law.

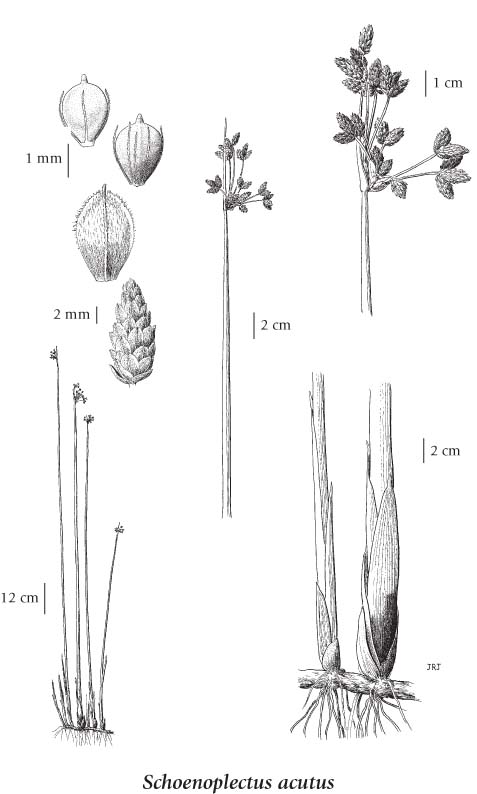

Those protocols are evolving—we’re not going to do the same thing that may have been done a thousand years ago. The context of colonization abruptly disrupts the continuity of that knowledge. We are learning and relearning at Chief Ya’anna Learning Village. We discussed how to build the Tuatukar eco cultural center and I asked our students: what would it take to build a traditional house? We all agreed we should first build a Gabrielino house and to do that we would have to gather and source the materials. Well, lo and behold, the entire ecosystem of the Los Angeles basin is 99% different than it was a hundred years ago. And that impacts our current reality. There isn’t enough tule growing in the city of Los Angeles to build one single Gabrielino house—in a place where there were hundreds of villages with tens of thousands of people. And there isn’t willow large enough, anywhere in the city of Los Angeles, to build one single house. So that’s a very clear indication of ecological health. It reminds us of the sensitivity of the environment that we’re living in, and speaks to the vulnerability that we saw during the conflagration.

LY:

For those unfamiliar with the geography, geology, and ecology of Los Angeles, can you ground us in the landscape?

GC:

To put things in perspective, our tribal territory on the coastline is from Malibu all the way down to Laguna Beach, and inland all the way into the San Gabriel Mountains and part of San Bernardino County, and out to the islands. If you’ve ever heard of Catalina Island, that’s one of our ancestral islands. So it encompasses a lot of Los Angeles County, Orange County, a little bit of Riverside, a little bit of San Bernardino County plus the four Southern Channel islands.

A lot of the work that my grandmother [Chief Ya’anna] did was in protecting these environmental spaces. She worked really diligently to protect the sage fields that we have left in the area. White sage is really important to our people, and our tribe is working on making sure people are aware of that fact and that white sage only grows from Central to Baja California, despite the fact that it is widely and commercially used around the world.

She also fought to protect Los Angeles County’s only coastal wetlands. That is where we source all those materials like the tule. Our rivers have now become channelized. The entire landscape is different because for over 200 years, the stewards of the land have not been taking care of it. Urbanization happens, colonization happens…We’re trying to scale back and think about the way things are built.

The infrastructure is not in place to support the number of people living in Los Angeles. Sewage gets dumped into the ocean with any rain. Sometimes [sewage gets dumped] just because the system is overburdened. Slowly but surely, all the coastal wetlands which serve as a filtration system, have been taken away. We have so many unique environments just in our territory—the mountains, oak woodlands, chaparral, coastal sagebrush. But it’s also difficult to manage at times because all our tribes—Gabrielino, Tongva, Kizh, Gabrielino-Shoshone—are not federally recognized.

Some of these protected spaces are also federal lands. There are different things that we’re not allowed to do, or we don’t have a say in what happens. So we are partnering up with environmental organizations that are doing the work. There are a lot of different ecosystems at play, even in our space at Ya’anna Village in northeast Los Angeles.

LY:

So much of your work, Patrisse, is about holding space for ceremony. I want to learn more about the Center for Art and Abolition and its part in the petition coalition.

Patrisse Cullors:

I always learn so much when I’m on these calls with our team and it’s beautiful to be just a witness to this conversation and to be inside it.

Los Angeles is the land of entertainment, great wealth and also deep poverty, and now thousands of people have been traumatized by a fire. Part of the work we have to do as we’re readdressing deep harms from the State—from the local, state and national level—is identifying which groups of people have been most harmed, and then working alongside and building coalition partnerships with those groups of people.

So how do we create a coalition that gets people excited about a new vision for Los Angeles: one that is centered in Indigenous wisdom, TEK, and the people who are the original stewards of this land? How can I, as a Black woman who has four generations here and who believes in deep allyship between Black and Indigenous communities, be in that vision? A Los Angeles that is Indigenous-led is actually a Los Angeles that is better for all of us, period. We know that because we just watched a Los Angeles that is not Indigenous led be burned; 30,000 acres and thousands of people lost their homes.

In this coalition we’ve been discussing questions like, How do we have this conversation around land back? How do we talk about TEK and understand that when we reposition Indigenous communities to be in right relationship to the land, we also reposition all of us to be in right relationship to the land. As allies, Lauren and I have talked about how we show up in this moment and have courageous conversations with the community of Los Angeles, our electeds, and also residents about being Indigenous led.

The way I do that is build a coalition, get many people involved, and model it. Being in partnership doesn’t mean we won’t make mistakes—that’s actually part of it. But we’re willing to come back to each other because we know there’s a greater fate, a greater destiny.

The Center for Art and Abolition is a project calling in an abolitionist aesthetics and looking at how we might aestheticize care and healing. How might we collectively create models that decenter white supremacy and patriarchy? This coalition is part of a callback to reparations, a callback to land back. These are acts of care. These are acts of abolition.

I’ve spent the last 20 years of my life doing a lot of destroying and abolishing, and I’m very proud of that work. My hope and desire is for the next 40 years of my life to be in deep alignment with communities and peoples where I can best support repair and rematriation.

LY:

Given this framework of reparative healing and rematriating land as a channel for us all to be in right relationship with the land, I want to understand the long-term vision of the petition.

LB:

Perhaps I can build a bridge to that question by returning to the beginning of the conversation about why we’re coming together. This firestorm we had in January is not an anomaly, it’s the norm. Back in 1998, Mike Davis wrote a seminal book called The Ecology of Fear that basically talks about the root of the problem being in the fact that Los Angeles is an engineered catastrophe waiting to happen. That fire, as we’ve seen it repeat, is actually not a natural disaster. It’s an engineering crisis. We’ve known this for a generation already, and we’ve seen massive fires happening regularly for this entire time. We’ve also seen that fire suppression is an industrial complex with billions being put into fighting fires as a military conquest; almost nothing is being put into what we know will work, which are prescribed burns, watershed restoration, and Indigenous stewardship. These things are severely underfunded. The point of the petition is to talk about the fact that this is a reparation of the entire colonized proposition of the city of LA that now has to be rethought, reorganized, and refunded.

There has been a seven generation mess made on these tribal lands. 140 years ago the train yard was built on top of the most sacred land of the Gabrielino, Tongva Kizh people in the principle flood basin. That basin is in downtown LA across from Metabolic Studio. Envisioning a Los Angeles seven generations from now cannot happen within the political structure of what exists. It can only happen through a public-private partnership. What we are asking for is for sanity to reemerge because all of us that are here, in our bodies, because our ancestors made good decisions. These new decisions need to be made around novel lines. The petition is meant to articulate a kind of beginning, and the coalition is about forming how we might start to really move into getting there.

This coalition is part of a callback to reparations, a callback to land back. These are acts of care. These are acts of abolition. – Patrisse Cullors, artist and founder of The Center for Art and Abolition

PC:

Thank you for also naming the military and the way in which the response has been a military response; the national guard was here. How anti-care is that to bring a military into a traumatized community?

We have about 6,000 signatures for this petition, and we’re ready to deliver it and move into phase 2 which is a conversation with the public and with our local electeds. The petition itself felt moving and visionary and the intention was to get people excited about what was possible beyond this current moment. Whenever I’ve worked on a campaign, I’m thinking about what is the greatest intervention we can make right now? There’s a great need for narrative intervention and a shift from the media focusing on political drama to return back to what is needed in this crisis.

LY:

Marcos, could you ground us in the Chief Ya’anna Learning Village and the ways that it is already modeling and showing Indigenous science at work as a place for visioning?

MA:

This has been an overtly intergenerational approach and in distinction to what public school might organize as a curriculum-based approach. Ours has centered around organizing the people that will make that relationship strong. And that’s included both alumni from our school that have gone on and pursued their own formation as educators and scientists, as well as other community youth at the university level that now have worked with us for several years. And then our high school age youth at the forefront of the leadership and all of this in concert with the tribal leadership in the Gabrielino-Shoshone nations tribal council: Gabrielle has taken a really active leadership role in collaboration, but also Nick Rocha and Rico Ramirez.

It expressed itself just last week when we were called to the land issues committee of the local neighborhood council because they were concerned we were feeding the coyotes and that the coyotes were presenting a growing threat. There was also a concern that the visual design of the landscape was deteriorating because of our approach and that it didn’t fit the ethos of the construction in the area and that we were producing a greater threat for fire. To be able to speak to the neighborhood council personalized the level of depth that our students represent. The scientists that work with us are able to communicate and elevate that level of consciousness around the truth of the matter on a community level.

That intersection with others that are not necessarily a core part of our school is important, but we’re navigating a space where the context of science as ceremony and education as ceremony also is intended to lead to pathways for Indigenous scientists to get an education because there is such a drastic defunding of access to Indigenous science and science teachers. With the current threat, we envision a different way of solving that issue by providing the coursework for our students to become scientists, but also for us to be able to evolve that science in a living, breathing way on the land as Indigenous peoples.

- 1. The American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA), which legalized traditional spirituality and ceremony, was passed by Congress in 1978.

- 2. The California Environmental Quality Act was passed in 1970 to put in place a protocol of analysis and public disclosure of environmental impact on proposed projects.

- 3. A note from Marcos: It should be stated that we’re using Gabrielino as a colonial term based on the San Gabriel mission because the complexity of Indigenous ontology goes beyond a quick introduction, but we’ll use that term for now. And it’s the term that the Gabrielino-Shoshone nation has used, as well as Tongva, and others use Kizh. It’s up to them.