In the spirit of Senegal’s ‘attaya’ tea rituals, the Attaya Hour is a series exploring unique emerging planetary education practices rooted in building locally grounded 21st century communities. Each conversation revolves around a new 21st century material culture unique to a community and location around the world (food, clothing, building or garden).

Invited guests are powerful examples of community-based leaders from around the world who are nurturing planetary pedagogies that are reinventing community-centered environmental activism. Each guest chooses their flavor of tea to kick off the conversation.

The Tea

Clare Owens:

What I really like about the tea set is that there’s three receptacles. At Squash yesterday, my team was asking how come there’s three cups? And I said, “Well, because it is for sharing.”

Mae-ling Lokko:

Yes, I learnt about the Senegalese practice of attaya from my friend Mamadou Dia who founded a fantastic organization in the north of Senegal called Hahatay. We visited last summer with my students and were able to experience “attaya” after a shared meal. In one of their local dishes thieboudienne, you eat from a central plate with your hands, and after they have attaya– where you drink three rounds of tea. Given we were on a schedule, the first time we did it, I did not get it. I was thinking “okay, this was nice but when are we getting back to the workshop?”.

Mamadou explained that the time shared over attaya tea is precious. Firstly, it is the hottest part of the day so who wants to go out there and roast? Secondly it is about creating space to address the very issues that are happening in our community, family or work space that would be swept under the rug. When this continues, it builds up and eventually explodes. So, the drawn out ceremony of three rounds of tea allows space and time for people to have a conversation, to find the words or to simply spend time with each other. Sometimes it was quiet as we ate, another someone started playing the guitar or just started discussing something that came up during the day. I got into it and by the end of the week I was like, “do we need to go back to work?”

CO:

Absolutely, today we’re so conditioned to be getting to work. But that is the work. Becky and I had set time aside for strategy meeting for Squash today from 9.30am to 2pm, and in the end we just walked around the park, collected leaves, went to a bakery, got something to eat, and just chimed in with each other and worked out the things we really needed to talk about.

In the end it was just so much more valuable than looking at a spreadsheet. What we needed today was to be with each other in nature, not just to be in front of a computer. It was so valuable and I would love to make a ritual of it and for it not to just be a fluke.

ML:

I’m glad we now have this time after six years to connect again. So where are you and what tea did you decide to have for “The Attaya Hour” today?

CO:

I’m in my favorite chair with two cushions and looking out at the park. I live inside a park (Princes Park) just up from Squash. It’s autumn, just after the equinox, and I’m looking at least 30 trees as I’m talking to you with so many different beautiful colors. It’s an extraordinary time of year.

This tea in this beautiful new gifted tea set is lemon verbena. I picked it yesterday from one of our lemon verbena plants in the kitchen garden behind Squash. Lemon verbena is sought after because it doesn’t grow as wildly as mint that just takes over space. Even though mint makes a wonderful tea, lemon verbena has this dual thing of being a real stress reliever and also energy enhancer depending on when you drink it in the day. I find if I drink it in the morning, it’s energizing. Although It’s not related to citrus, at night it is very soothing. It helps with muscles and digestion. When we have our open days in the garden, in the community garden, this is the tea that everybody wants. It’s a communal drink. We have lunch together every Wednesday of the year, when the gardeners get together. And so we will make a big teapot of lemon verbena and then we’ll have it after lunch. It’s very transporting and delicious.

Attaya Round 1: The DNA of Squash

ML:

When I first visited Squash in 2018, I remember thinking how unusual it was to have such a diverse cross-section of British society in one space sharing high quality food. What have been the ingredients for creating that kind of environment?

CO:

I think our practice has been, and when I say we, I’m referring to a lot of different people doing a lot of different things at Squash at many different timescales, it’s been about wanting to make spaces where people feel not only that they belong, but also that they can give of themselves, be themselves and also exchange with others in that place. Before 2018 when you visited, we didn’t have a physical space. We designed spaces wherever we went, whether that’s putting a table, sofa, or couch on the street, creating a garden or making a pop-up party in a community hall. Through this, we became very thoughtful about how to make people comfortable in space, whether that’s physically or emotionally. It is really important to us how people feel when they’re with us.

Last Saturday, for example, for the Liverpool Irish Festival, the acclaimed writer, television programme maker and traveller Manchán Magan was doing a beautiful talk about the Irish language through the making of sourdough bread and butter. So we went with our sourdough bakers, Eddie and Julie. Afterwards, he was gracious to accept our invitation to visit Squash. When he came into the space, he got it straight away; that was a very multifarious space that is both the product and continuing journey of so many people’s hopes and ambitions. And I think there’s something about the collective, the community, that when you bring hope and ambition and generate a lot of warmth and generosity, where incredible things can happen and a lot of difficult things become possible. The true meaning of the word hospitality is really important to us, we welcome strangers. It feels like the privilege of my life to be able to create a space that I once really needed. At the time I didn’t even really know I needed it.

ML:

You said you didn’t even know you needed it. Where were you? At what point in your life did you start to see the seeds of Squash come together?

CO:

Squash came together when I was around 30, and I’m 52 now. It was born out of myself and my very dear friend Becky Vipond. We were both social artists and met at a community cultural project at the Black E community project in Liverpool. At that time, I was a curator and a producer working for the Bluecoat Arts Centre in Liverpool. I was working on many festivals and bringing together lots of different people, and I really loved that. Becky was an art teacher at that point.

At the time in our lives, we both had young children and found ourselves asking what was it we wanted to do? We could go down a path where we continue to work for art or education organizations or to follow the urge to do our own work in the world. After working myself in a few arts organizations, whilst I learned a lot, I felt very restricted. So we made the decision at 30 to purely work freelance together and trust in the friendship. It’s that trust that has carried us for 20 odd years. We are very different people but our values are very similar. So we really compliment each other and it’s a beautiful thing. And in terms of what I needed then was to belong myself. I needed to feel nurtured to nurture myself and others. To think more was possible in community.

So my journey has been from being a curator, producer, administrator of arts, to becoming an artist myself has been a really big change for me in this 20 year journey. When we started Squash, I wasn’t interested in being an administrator of other people’s joy, I wanted to be in it. And I don’t think we could have done it any other way than to show up as ourselves. That’s something we really encourage in people. Whilst it’s really important to have whatever you want to call it, work-life balance, I think to be able to be more of yourself in a work context and to also understand it as a life to which you can bring more than one thing.

ML:

Absolutely. And I love the idea of you seeing this form of work, social practice as your art. So if this is your art, and relationships have come out of this practice over the last 20 years, who would you say today is part of this Squash community? How big is this community and how elastic is it over time?

CO:

It’s very long term. As I mentioned before, there’s people who have been with us right from the beginning. So we have people that work with us or volunteer with us that we met as children, as youth workers, who are still part of the picture. People who are now in their thirties and forties.

There’s a lot of people who live locally who are involved in Squash. And some of those journeys have been very different. Some, for the last 15, 20 years have consistent contact; like are with us every Wednesday, every Friday, every Saturday, coming in to do various things. There’s other people who might come by less frequently or might move away and then come back.

And then there’s just people who are rooting for us, people who use the coffee shop, people who come to sessions, people who volunteer, people who work here. If people move on, they’re on our freelance roster. So when we do really big gigs, people can come in. We have associate artists, and green infrastructure practitioners. Essentially Squash is nature-based environmental art, green infrastructure and enterprise collective.

We have come a long way as a community business that allows us to make our own income and not just become reliant on the state or others for funding. Developing enterprises is a huge part of what we do, for example, this is the seventh year of our women’s Food Biz program.

ML:

That’s incredible. I wonder if you have your own theories as to why, first of all, Liverpool is able to sustain and grow these types of programming and spaces, and also whether on a smaller scale, is there something unique about your neighborhood in Liverpool that activated its formation and endurance over the years?

CO:

I haven’t lived as an adult anywhere else, so I only know what I know here. I have travelled to lots of places, and there is some magic about Liverpool and especially the postcode of L8 where I’ve lived for over 30 years.

Liverpool is a city with a history of endurance. As a one of the major global centres of transatlantic slavery, there are of course ongoing ramifications and related trauma and so much unravelling and healing justice to continue with around all of this, which is most keenly felt in L8; the most culturally diverse area of the city where many people experience multiple inequalities. After the 1981 uprisings in Liverpool 8, prime minister Margaret Thatcher famously wanted ‘managed decline’ for Liverpool. But Liverpool’s having none of that.

I’ve seen and experienced many examples of people committed to positive change from the grassroots up. People having a say, showing up and actually being able to affect things. A lot of that is still done with very little resource and a lot of persistence and hope. Like many places across the world, people work with what they’ve got. I mean, it’s not to say that we’ve got it all sorted here, it’s a real struggle. But I think we’ve started working together more. There’s lots of organisations starting to look to each other and asking, can we do something together? Can we share this resource? Can we talk through this problem? Ten years ago that wasn’t happening as much.

We’re lucky to have and work alongside so many community engaged practices on and around Windsor Street including 20 Stories High, Granby 4 Streets, Family Refugee Support Project, Scouse Flower House, Friends of Princes Park and Writing on the Wall plus COoL (creative arts organisations of Liverpool) a unique network of grassroots arts practices. And shout out to our beloved partner Habibti Liverpool, an amazing group of women who solidarity fundraise through sustainable, pre-loved fashion, supporting life-saving services at Al-Sabeen Maternal Hospital in Sana’a, Yemen.

I’ve recently travelled to the States and Ireland researching long-term participatory community practices and visited a lot of incredible community gardens and arts projects. Much of our discussions were about the security and ownership of land & buildings for the people with folks often not knowing if they could keep a garden, an artist studio or community centre. It made me more aware of how incredibly important it is for Squash to have a community-owned building and land. In the US the word resilience was going around a lot – everywhere I went, and I hear it here too. Why should people have to be constantly resilient? For so many, it’s so hard to have to keep going on. Why do people have to fight for land to grow food, fight to do these amazing, life-giving projects. In New Orleans especially, people are trying to do this essential, incredible work in the face of such adversity. One that really stood out for me was Solitary Gardens, an art project about carceral justice and gardening. We have so much to learn from this boldness, tenderness and humanity.

Attaya Round 2: Squash Planetary Pedagogy

ML:

I believe that what you’ve been doing over the past 20 years is a form of planetary pedagogy, a way of teaching people to live and deal with adversity together. Can we begin with security – how is Squash positioned in terms of ownership, in terms of land or other types of resources, and how has this developed over time?

CO:

Up until 2013-2014, we had been gardening, cooking and making art in the Windsor Street area of L8 for about five to six years in different spaces that were owned by other people. As a group of gardeners, cooks, artists, we just thought, we don’t want to be at the whim of changes by a developer or the council. If we were going to put roots down, then we needed to own our space.

At that time it seemed that urban gardening was of interest to politicians, councillors and local authorities but only in a superficial way with funding for a few community growing beds here and there. In the UK we have allotments; small plots of land in a communal area owned by the local authority, which grew after the two World Wars, to provide a source of food for urban working class communities. They are really oversubscribed so you can’t get one for four or more years from when you sign up. And a lot of people don’t have gardens, instead small backyards.

We decided to develop Squash into a community interest company. This is one of many organisational structures we considered. We didn’t want to go down the charitable route. While some charities do great work, it felt like a sort of box we had to squeeze into. Being a charity didn’t feel like a fit to us as this model uses ‘us and them’ language around ‘helping poor people’. We were and remain interested in exchanging with people and being a community that makes decisions together. We also knew that commerce or trade was going to be part of that mix. Ultimately, we wanted to have independence around our income and a way to build and nurture and add to the current local economy. We are also interested in funders of our work to understand that long-term, core funding is essential when it comes to us being well nurtured so we can flourish. Some of the larger funds and trusts are now getting it and considering much longer timeframes of 5-10 years, not just 1-3 years.

So the community interest company model means that you can trade, you can be entrepreneurial, whilst having charitable or social aims and values. That was really important to us. We wanted our community to own land. The first attempt to buy a piece of land didn’t work out. In a way it was a silver lining because we then found this piece of land that was on the street we had worked on for years. It was near our original community garden. The land had become a dumping ground. It was in a very residential area that had historically been under-invested in. It was basically a concrete slab with lots of debris on it.

We found out the land belonged to the council. We approached them and asked them if we could have it for free, since we were doing work that would benefit our community, but they said it would take years to get through layers of bureaucracy.

We couldn’t wait as we had a time limited grant from a social investment business, a governmental body that supports community run businesses. So we were able through them and some other funders, including Power to Change, which is all about community run and led businesses in the rural and urban areas, to purchase the land at market value from the council. That’s the best they could do for us.

The building was designed by 30 local people, mostly gardeners. It is a beautiful, timber-framed building with a low carbon footprint. The thick walls are insulated with newspaper, it has solar panels,sustainable grown Scottish larch cladding and a recycled steel roof among many other things. And it cost around £400k to build, which is extraordinarily low cost. For a building footprint of 27 m x 8m, it is amazing value. It houses our community run food shop, vegetarian cafe and catering business plus our ‘Front Room’ event and activity space and some time gallery, a kitchen garden and our office. The building is a locked asset within our constitution, which means that it will always be for community use in perpetuity. It can never become a hotel. It could become a community hotel, but it cannot become strictly commercial or anything that wouldn’t be for community value. So that was a really important part of our journey.

We also received loads of incredibly helpful advice from different places about what to do and what not to do, from how much storage to make, to how to employ a builder, to so many different things we learned and that we can now pass on to people. We get a lot of people coming to us for advice, which we are totally up for sharing. It’s almost the mistakes that are more interesting than the things we got right.

So yeah, we own that land. We own the building. When anyone comes in and says, are you the boss or who’s in charge? Anyone in the building can go, I am. Sometimes people don’t want to, they point to me or Becky, but it’s like, actually everyone owns that building. They do own it. Everyone owns it.

ML:

How many members formally makeup Squash and how does one become a member?

CO:

We’ve got about 200 active members who have signed up and 8 trustees. You have to be either born in L8, come from L8, or working, volunteering, or living in L8 to be a member or trustee. This just means that you are deeply invested in the locality. Members are from, or have a deep connection to the area.

As well as weekly drop ins, we have members action days quarterly, and we have our annual general meeting, which is always great. There’s lots more ways we would like people to be more involved, but that is an ongoing thing. A lot of members use the facilities for meetings, parties or if they have ideas they want to try out. We host a lot of different local forums and support young community businesses with free space and advice. There’s lots of different people who use the building and almost all of them are members.

ML:

I remember when we did the workshops there for my exhibition “Hack the Root” as part of the Liverpool Biennial, there were also gardening spaces in schools or on the street that were also part of the Squash network. Are there a broader set of spaces in the city that also indirectly or directly Squash and help to shape programming?

CO:

We have several community garden spaces on Windsor Street. And we’ve helped people make gardens over the years but don’t do that a lot now. We invite people to come to train with us at Squash. Through the Liverpool Biennial, 15 years ago, we had a very brilliant learning experience and learning curve. There was a disused school that had a big outside space. We wanted to experiment with our very first field kitchen and pantry, so we spent a season growing and working in this school grounds. We were able to host a conference, invite artists and make some pop-up structures.

It was great practice to think about what we were doing and just the beginning of where we were trying to find our own home as Squash. And it was a really important juncture because we learnt that where we do our practice needs to be where we live, where the majority of us live.

When we first started, you could have counted community gardening organisations on one hand in Liverpool, but now it feels like a lot more people are getting involved in communal gardening, cultivating more urban nature with food and flower growing. We still get requests for us to build gardens for other projects. But we say, come and see our garden, ask questions then go and do what you need to do in your space, which is a much more sustainable way of doing it.

A lot of people are focused on the physical space whereas for us it’s what we create in the space that matters, whether you’ve got a playing field or a long established permaculture forest garden. It’s got to be how people are in space with nature. It’s a very slow paced practice to build the space together. And that’s a really important thing for us.

In recent years we’ve been composting sessions with wonderful local compost expert Minna from Compost Works, developed some of her practice in our gardens before she launched her own compost business. She does beginner composting sessions as well as really in-depth, bigger scale composting training.

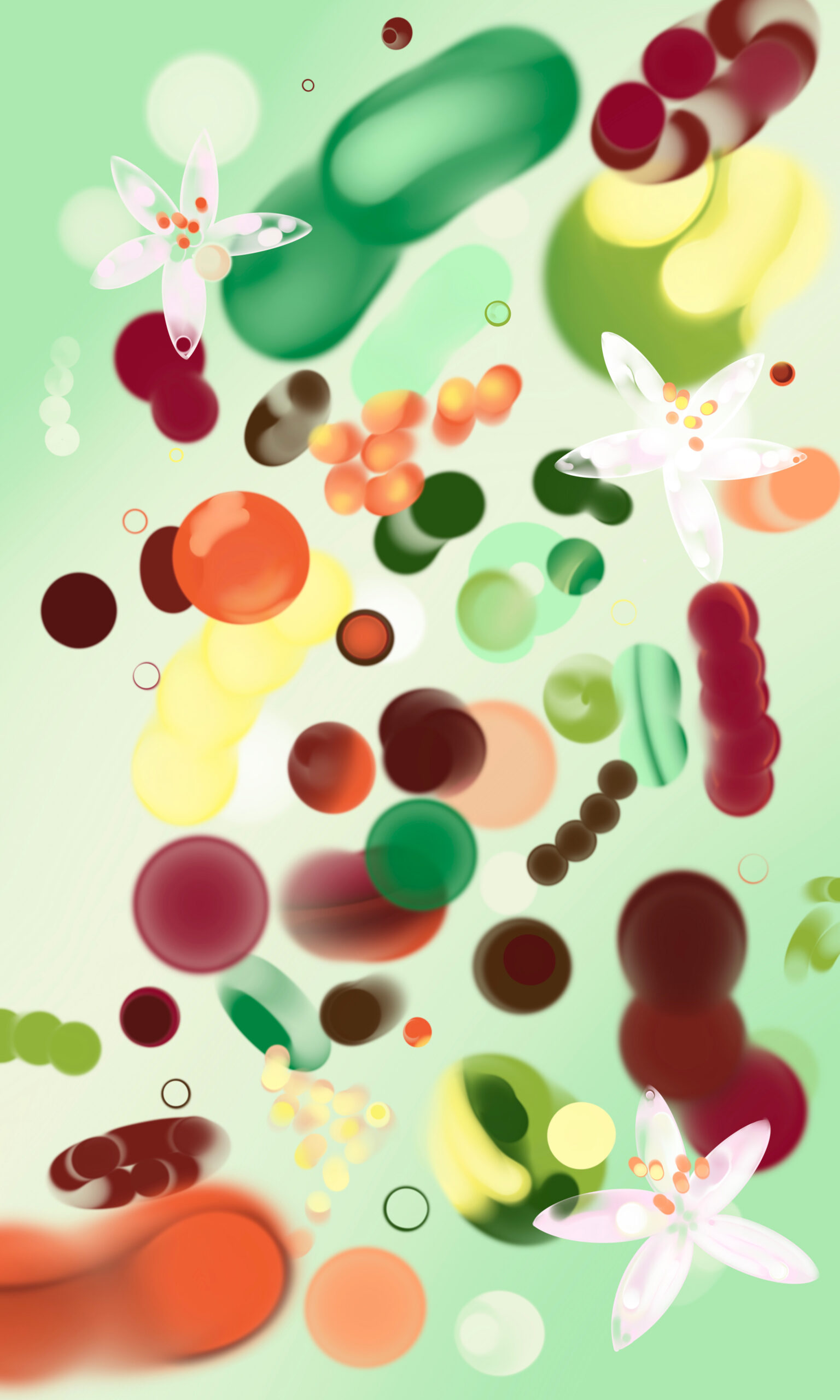

As part of the growing year, it’s important for us that we host joyful, traditional land-based gatherings. Every February, the start of the growing year we host Liverpool’s ‘Seed Swap & Share. We welcome over a hundred gardeners from different parts of the city and from across the region. Organizations and individuals who seeds they’ve saved form plants they’ve grown to share with other gardeners in the city. It’s so beautiful on so many levels that you can see the seeds of the city. Also now in its 14th year is the Toxteth Seed Library – our own collection of saved seeds from our gardens including the special seed garden behind Toxteth Library. Packets of our seeds are available in the shop.

I mean, we get seeds from all over. Everywhere we grow, I mean, we have four gardens up and down that street, and we let things go to seed, and then we have the seed. We also have the seed save. On the fall equinox, people come with their seed heads or their pods. We teach lots of different techniques to extract the seed from the pods and the husks. And it’s a beautiful communal activity. We make seed packets, draw seeds or whatever it is that really connects those things as well as the harvest auction.

For the past 9 years, we have done a harvest auction. It’s a massive solidarity fundraiser. People from all over the city and beyond bring their fruit and vegetables that they’ve grown, and we auction it. People get so excited about secret apples from Sefton Park that have been grown surreptitiously behind a bush and all the other beautiful stories of how urban food comes to be grown. There is storytelling and meaning-making behind the items auctioned which is so important when it comes to food. Capitalism has disenfranchised us from the most important things that make us human and what makes nature. Nature is being able to touch it, feel it, grow it, harvest it, eat it. Every year people want to talk more about it.

Attaya Round 3: The School of Squash

ML:

If you were to imagine the school of Squash, what would a calendar year be like? What would be your tools for teaching or how would you evaluate students?

CO:

I think consistency is really important and that people can rely on the fact that whenever they come, they will be taken seriously. Training is really important, but exchange is important too.

A seasonal approach is key for our practice, and a land-based approach is too. So even if it’s like a spring growing workshop that’s pretty much like it’s got a beginning, middle and end, we would still accompany that with food. So food and drink, hospitality – to create a space that is welcoming and is open to what the people are bringing is so important to us.

Working with experts is one thing, but the local expert is massively important. We’ve had seed experts, for example, who have come with incredible knowledge, but very little ability to share it. Working with a lot of different people and bringing a lot of different people’s lived experience into the different things that we do is critical. And also really learning from what we’ve done, taking a pause to really consider what it is that we’re offering and then how did it actually really go? So the evaluation stuff is super important to us. We evaluate our participants by how they tell us they feel and the quality of their experiences with us.

Re training and learning, we also work with many more formal educational settings; schools, colleges and universities. Liverpool University’s Masters Program in Public Health come back to us each year for a ‘radical day’. Doctors, nurses and health commissioners come to Squash and see people’s lived experience in action and they see what so-called alternative, non-traditional community healthful space actually can be, and it’s very affecting for them. They are really moved by it. And we have people coming back year after year saying ‘I did that with you five years ago and it really changed my mind on how to speak to patients or how to refer patients or how to really consider my commissioning process.’ In all training and learning we incorporate practical, nature-based elements because people need it. We can’t just talk about it. We can’t just do a slideshow.

In the community we work with so many different people; sometimes we work with people who are really, really struggling. A lot of people we work with have been really let down in society. They’ve had a very hard time. So in terms of that, all of our work has to be very well resourced with people who know how to hold space for people. Our team are experts in building relationships and trust with people. Whatever the subject, whether it’s compost, cooking or whatever it is, we have to have people who can really be with people.

We like to have really good quality spaces and really good quality equipment and materials. Good quality food goes without saying of course at Squash. In so much community work that I witness, even the food, which is so important to us, is the last thought on people’s minds. It’s a packet of cheap biscuits and some instant coffee. Some people think it’s snobby that we want something really good. But we believe that people who’ve been let down, and all people, but especially people who’ve historically been let down deserve the best we can get.

ML:

I mean I still think about my time during the Liverpool Biennial and the quality of food and conversations that I had at Squash.

CO:

We are very proud that last week we won Food Venue of the Year at the Merseyside Independent Business Awards. We also won the BBC Food & Farming Award for best shop in 2019, the year after you came to see us. For a small community organisation in L8, which is not in the south of England, that recognition was huge for everyone; our team, everybody in the wider community, it was for them.

ML:

You’ve talked about Squash that have elements of a form of public health infrastructure. Nutrition, mental health and wellbeing, immersion in nature in local neighborhoods and the city and beyond. Can you also talk about the generative side of what you’re doing in terms of the women food business accelerator?

CO:

Before we opened the building in 2018, we used to run a lot of pop-up cafes and growing and cooking workshops in the streets. We became very aware that there were a lot of women in our community who had English as a second language and were very socially isolated. They may have arrived as asylum seekers, refugees or economic immigrants. They reported not having much sisterhood, camaraderie or community connection. Many had a very high level of culinary skill. They may have amazing ideas that they wanted to take to market, but wouldn’t ever have the opportunity or the capital or the way to do it. So we thought, let’s just try to do some sort of training course. Confidence-building was key.

So, Women’s Food Biz is now a long term annual programme where trainees get to meet loads of other women in the city that have set up successful hospitality or catering businesses. And they get to volunteer there, they get to be with them, they get to come and report back. They get to try out loads of ways of doing things. They get to try out their own recipes. They get to try out each other’s food. They get to know each other. So many friendships have been formed. We’ve trained 40-50 women each year for the last seven years who’ve gone on to work and volunteer in hospitality, cook healthier foods for themselves and their families and feel more independent..

Our current kitchen manager Edlira Bunga came to us through Women’s Food Biz six years ago. She’s an extraordinary, amazing person originally from Albania. A couple of years ago, Edi mentioned in passing that she milked cows and made dairy products back home from the age of 4 to the age of 18. It was kind of a throwaway comment, but this incredible food skill is now a big part of what we do. Edi now makes the most delicious cream cheese and butter every week. The wonderful Fozia Choudhry came on to Food Biz , then worked in the Squash kitchen for 18 months. She always had the idea of owning her own restaurant. She started with a street food pop-up in a shipping container and now has her own successful restaurant.

It has worked really well. We’ve secured money from the Workers’ Education Authority and Liverpool City Region to support people with mathematics. So we’ve incorporated maths in the training, which is really important in cooking.

Our wonderful patron Andi Oliver who’s an incredible chef, author and broadcaster who hosts the BBC’s Great British Menu, is a huge supporter of our women food biz trainees. She visited for the Autumn Equinox last month and hosted the women for an extraordinary afternoon tea and conversation about wellbeing.

ML:

I wanted to ask a last question to end on. What would you say are the rituals or milestones that mark programming at Squash?

CO:

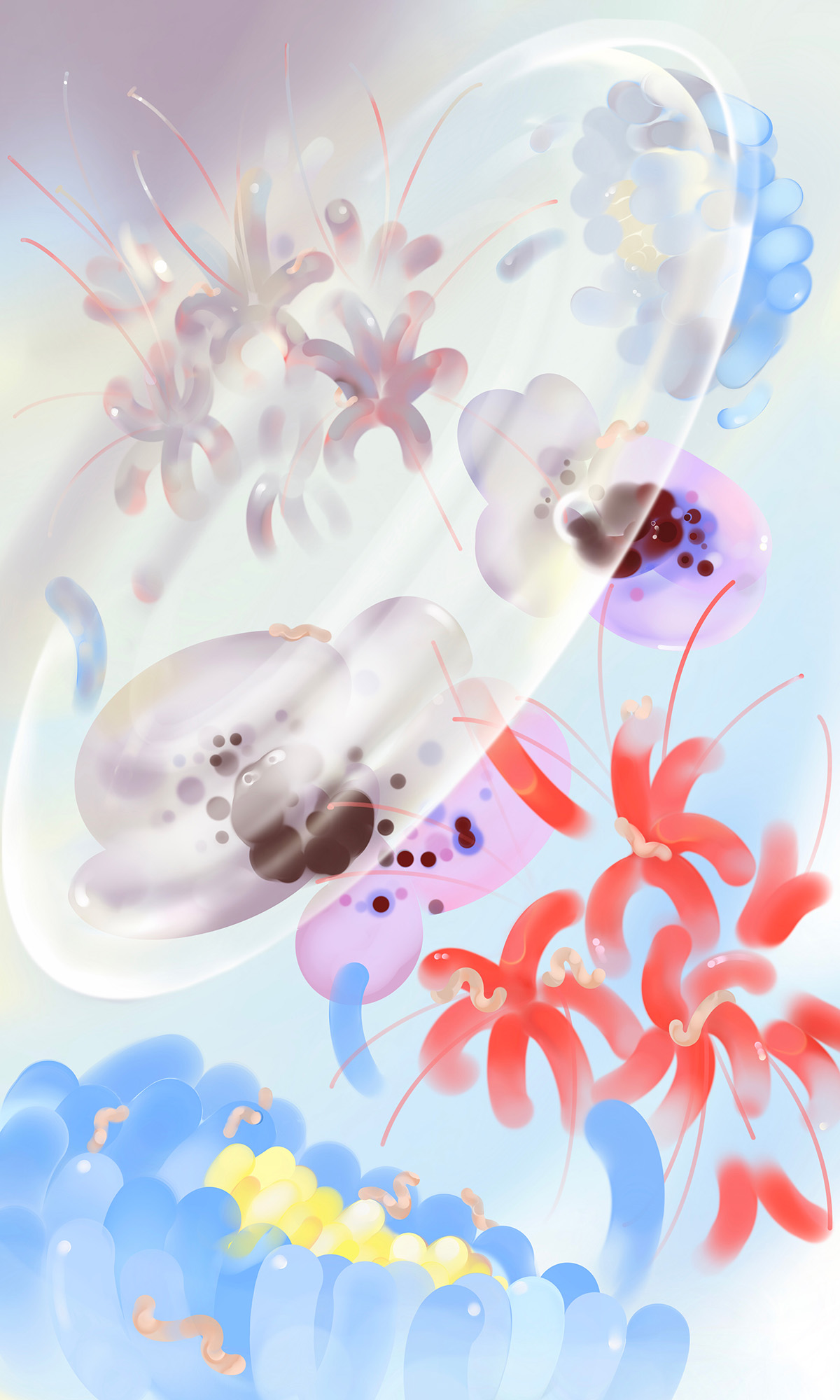

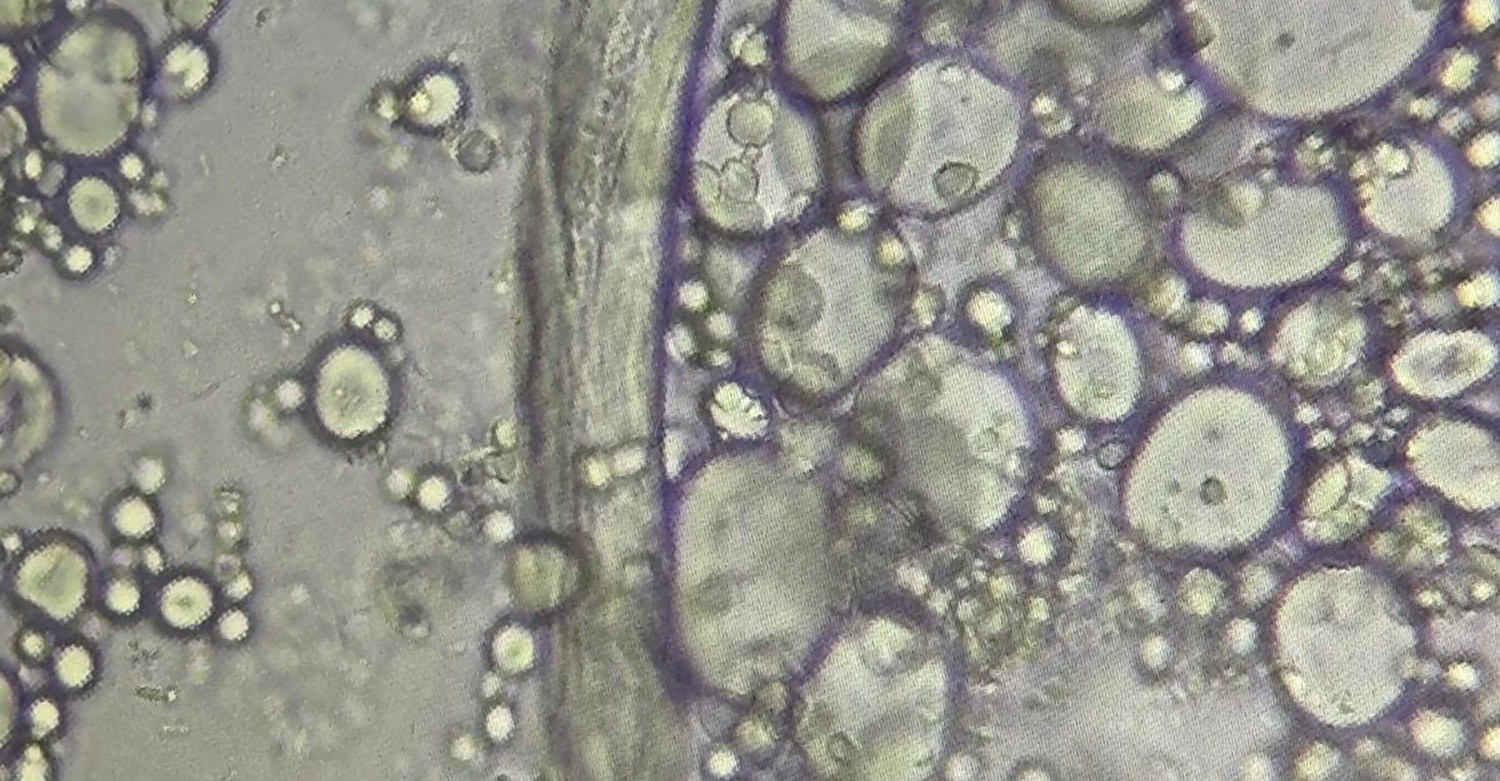

Well, our overarching guide, our vision, is the 100 Year Street; the ultimate milestone! It begins with an understanding that we are all nature and that nature is such an important member of our community. When we began the community garden in 2010, 15 years ago, we planted these apple trees. Really, it was an old pub garden. A lot of the land was in really bad shape but apple trees and fruit trees are really good at being in bad soil and they help regenerate it, as does mycelium of course.

Our first question was what’s the time base for this? We looked up how long apple trees live for. If they’re nurtured well, and of course there are many different varieties and many different sizes and stocks, but if looked after well, like a human being, an apple can live for up to a hundred years or longer. So we thought, right, what about a hundred year project? Let’s think about this as a hundred year program.

At that time the youngest Squash member was 1 yr old Alina and an 80 yr old Jeff. Alina is now a teenager, and Jeff passed away earlier this year. We wanted to have a timeframe through which to do our work. So that’s one timeframe. That’s one very, very long-term ritual that we honor. It’s a commitment to the long term.

Another framework we hold is between the spring and the oak. Liverpool’s only accessible spring is at one end of Windsor Street in St. James gardens and a very old Turkey oak tree is at the other end, inside Princes Park. The root and the crown of the street in chakra terms.

Then the other ritual space is cyclical; the eightfold year. In the eightfold year, there are eight points in the year where we can stop and be with each other; an excuse for a fire, a chat, eating, thinking about how we’re all doing, how is the land doing, how are the plants doing, how are the animals doing? Honor people with us, people who have left us, all of those things.

Those eight points are: four crossfire festivals of pre-Christian Gaelic mythology and paganism. So they are Imbolc in February, Beltane in May, Lughnasadh in August, and Samhain at the beginning of November. The other four that are between them; the spring equinox in March, summer solstice in June, autumn/fall, equinox and winter solstice. Between them is called the fold. It’s the fold between these points.

At these festivals we work together with our associate artists in creating exceptional spaces of belonging, where people can be thoughtful, still, dancing, resting, drawing, talking, adding to an altar, singing, planting, embroidering.

The rituals that we do at those points always include fire. Fire is just so important to human beings. Fire is for warmth, for cleansing, for watching each other’s faces in the reflection, for singing around, for talking around, for crying around and holding hands around.

We try to have fires in public spaces, so we have them in our garden, but we also have them on the street. Doing work on the street is really important to us. You’ve got to have spaces where people feel like they can join you at some point. Sometimes people won’t want to walk into a building or into a garden, but they might want to just meet you outside by fire on the street. So fire is really important. Music, food and drink is really important.

People have very different rituals because we live in such a multicultural community, people bring all sorts of different rituals through and there is space and encouragement for all of that. The eight festivals are sort of the beginning and then there’s loads of other things around that. The one we’re preparing for now is on the 1st of November. It’s very akin to a lot of different cultures including Mexican Day of the Dead, which is an honoring of the ancestors. There’s often a lot of fires at that time. The term ‘bonfire’ comes from fires where cattle would be eaten and then bones burnt. So these old rituals we sort of nod to and try to understand something of.

But we don’t just look backwards, we’re looking forward. We are going to be having an altar where people can come and write the name of someone who’s passed away. So we can all look together at all the names of the people that are no longer with us, whether that’s somebody known to them or unknown to them, whether that’s a family member or somebody who’s been murdered in the horrific genocides that are happening across the world, we hold space for many members of our community and they hold space for us to try and process and grieve these things that are happening that very much affect people in our community.

We have a lot of community members with family in many parts of the world where horrific things are occurring, and being together is so important. We always have craft making because it’s so important. To be able to make sense of something by making something with your hands is super important. Mindful crafting is really important. This time we’ll be making stuff with wool that we’ve collected. Having that hand eye coordination, hand eye, hand, mind, hand, heart is super important. And then being able to create something, whatever it is for, is super important.

These rituals are evolving based on who initiates them and what is going on at any given time. We have done many walking rituals. One summer solstice during Covid when only six of us were allowed to walk out together we made a chakras of the street walk.

On the summer solstice one year, the shortest night of the year with under seven hours of darkness, we walked 11 miles around all of the major oaks of south Liverpool, together in the dark and then arrived back at our Princes park at dawn. Being in your city in unusual ways and times, feeling the nature and the sounds and smells of night, it’s quite rare and it really helps you understand the place you live in such a profound way. Walking through spaces together and feeling ourselves changing in the season is a real privilege.

What we are very interested in at the moment is making an almanac which is like a farmer’s guide of the year. The etymology of almanac is ‘climate’ in Arabic or ‘calendar’ from the Greek. Originally farmers would use them to help with the growing year and it would include times of the tide and moon tracking and such. For Squash it’s interesting to think about a living almanac, a prediction of what may happen in nature during the year on and around Windsor Street. A collection of happenings and possibilities. An L8 version with rituals threaded through it and that also considers how our climate is changing.

ML:

Thank you Clare. What a beautiful way to think about the L8 Calendar. I’d love to discuss so many aspects of this conversation with you in the follow up, but thank you for bringing me into your world and journey.