In 2019, artist and researcher Asunción Molinos Gordo began In Transit (Botany of a Journey), a project that emerged from a serendipitous experience during a research trip to a waste management plant. While exploring the facility, she became captivated by the intricate infrastructure that filters the city’s fecal matter before channeling it into a drying pool. During the tour, her guide pointed out a phenomenon— tiny sprouts peeking out from the surface of the waste, signaling the early stages of germination.

Based in the hills outside Madrid, Asunción’s practice is largely influenced by her family’s agricultural lineage and explores borders, globality and interconnectivity. Her practice is fluid, adapting materials and processes to meet the needs of each project. Deeply rooted in the study of common peasantry, her research examines farmers as both knowledge-bearers and an often-overlooked part of contemporary culture.

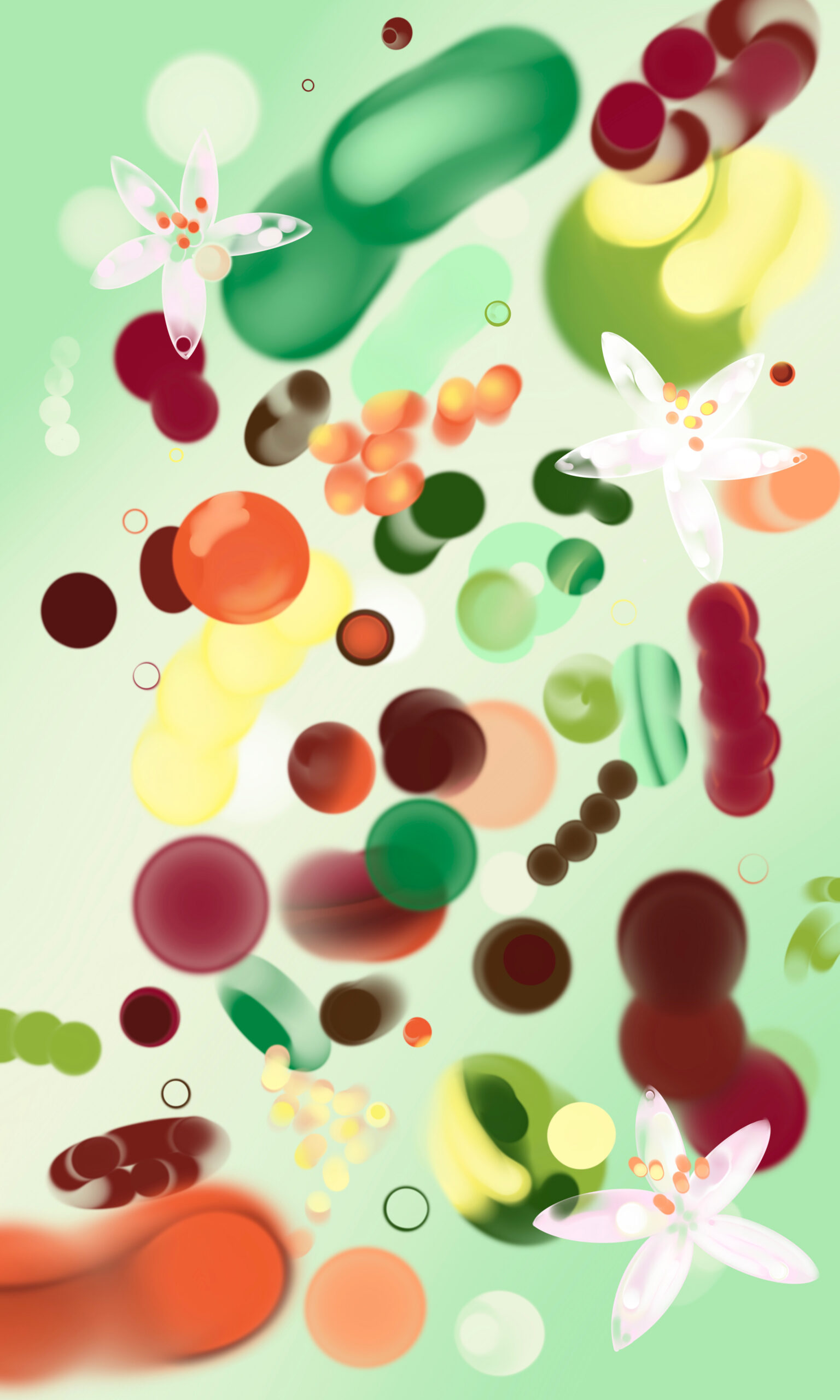

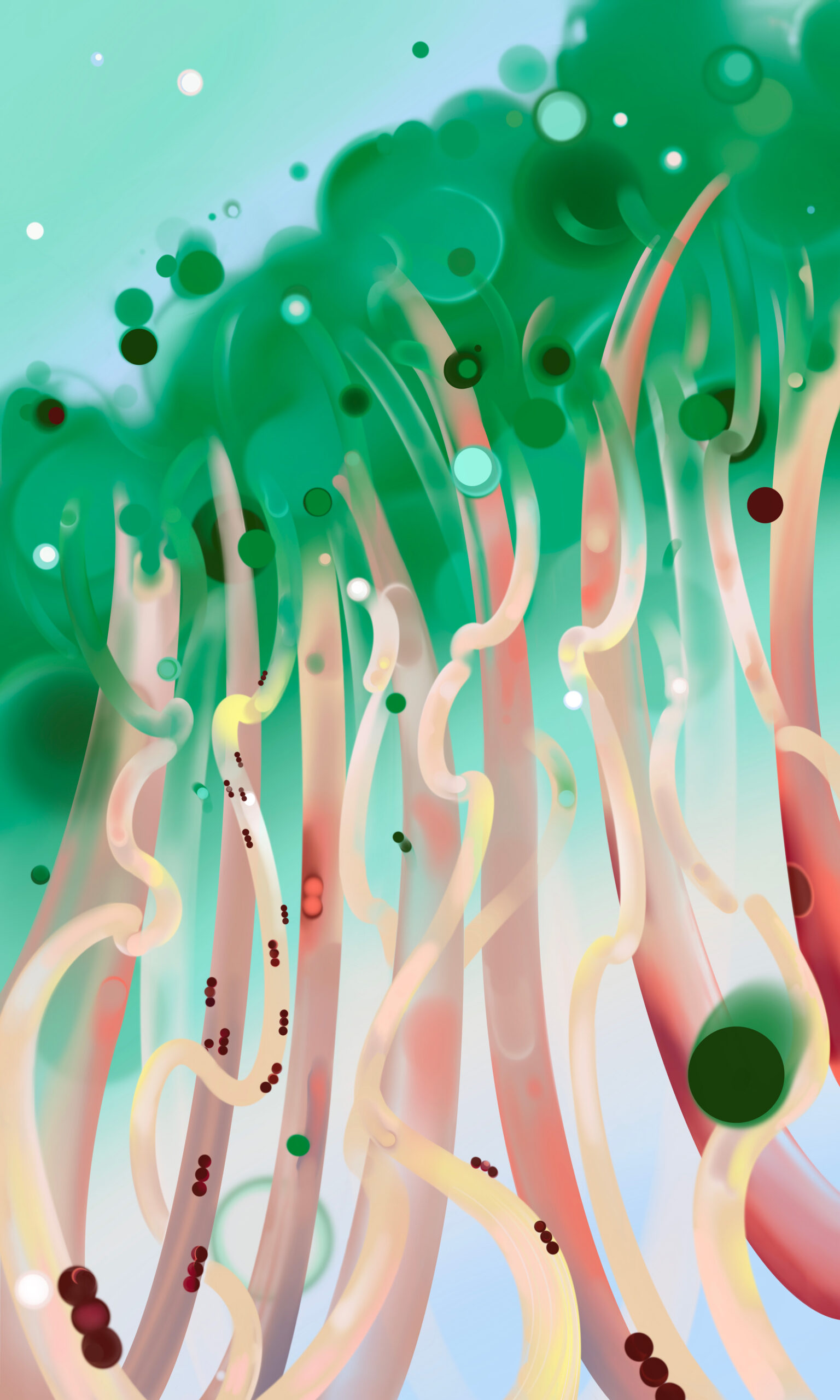

When the Jameel Arts Centre in Dubai invited Asunción to collaborate on a project, she used the opportunity to expand her exploration of waste systems by creating a garden with seeds recovered from fecal matter at the Al Aweer waste management plant. Because Dubai is a diverse metropolis with roughly 90 million visitors each year, this sample of fecal matter represented a multitude of communities, cultures and experiences. Asunción and her team worked closely with a farm outside of the city to safely filter and dry out the fecal matter and then transport it to the garden, where the seeds were left to freely germinate. Initially, the garden was left to grow in the random organization of the seeds. Later, Kumar, a farmer from Carola, was brought in to identify and arrange the plants, which included lemons, oranges, pomegranates, mustard, chilies, and tomatoes. Using companion planting methods, they cultivated a range of species—all resilient enough to survive the human digestive system. The entire duration of the project followed the agricultural calendar.

In Transit is a full cycle of regeneration. From the beginning to end, these seeds have transformed through labor processes, with humans as both facilitators and unknowing hosts. The labor embedded in food systems is often invisible—just as the work of those who harvest and transport our food remains unseen. This project renders those labor processes tangible, making visible the intricate connections between human, agricultural and ecological systems.

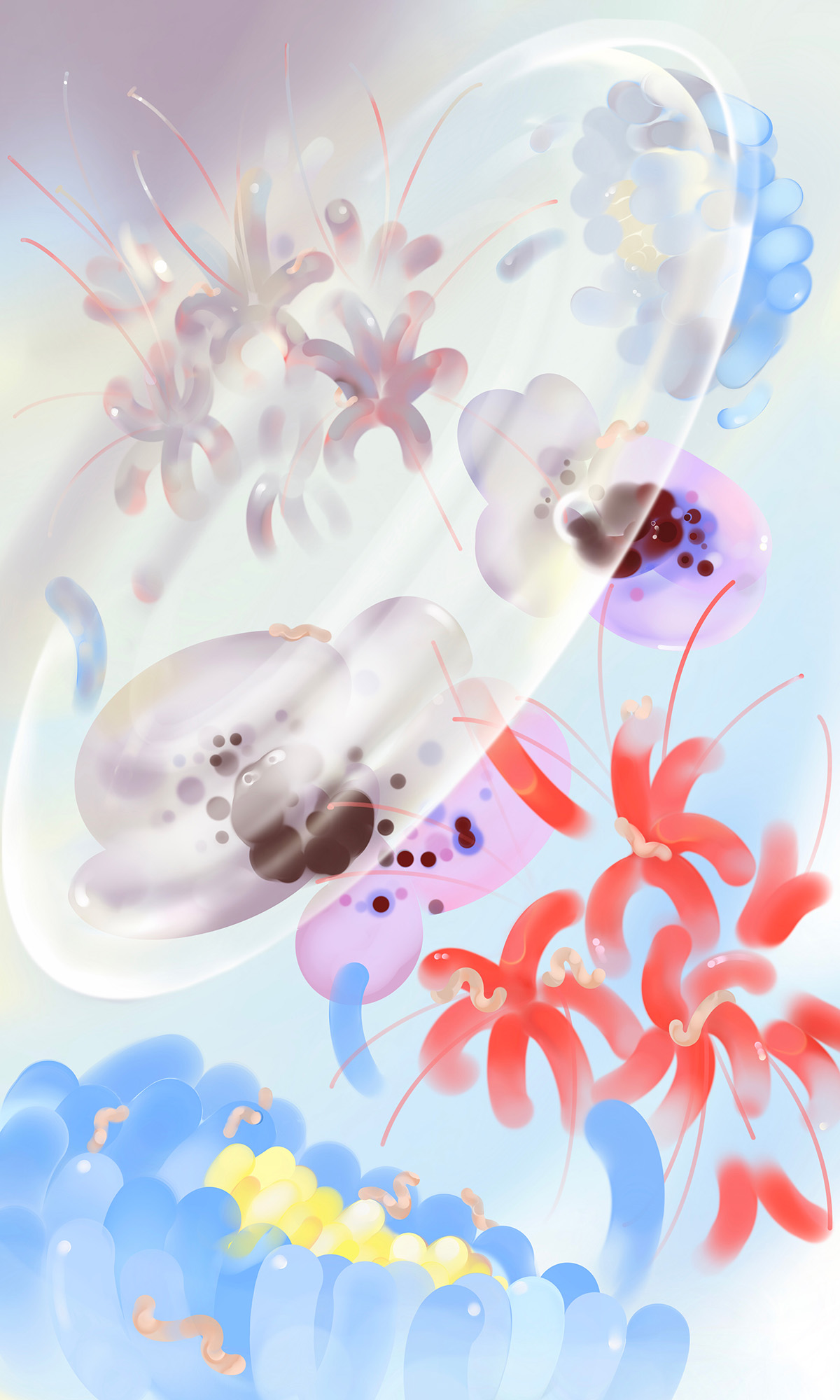

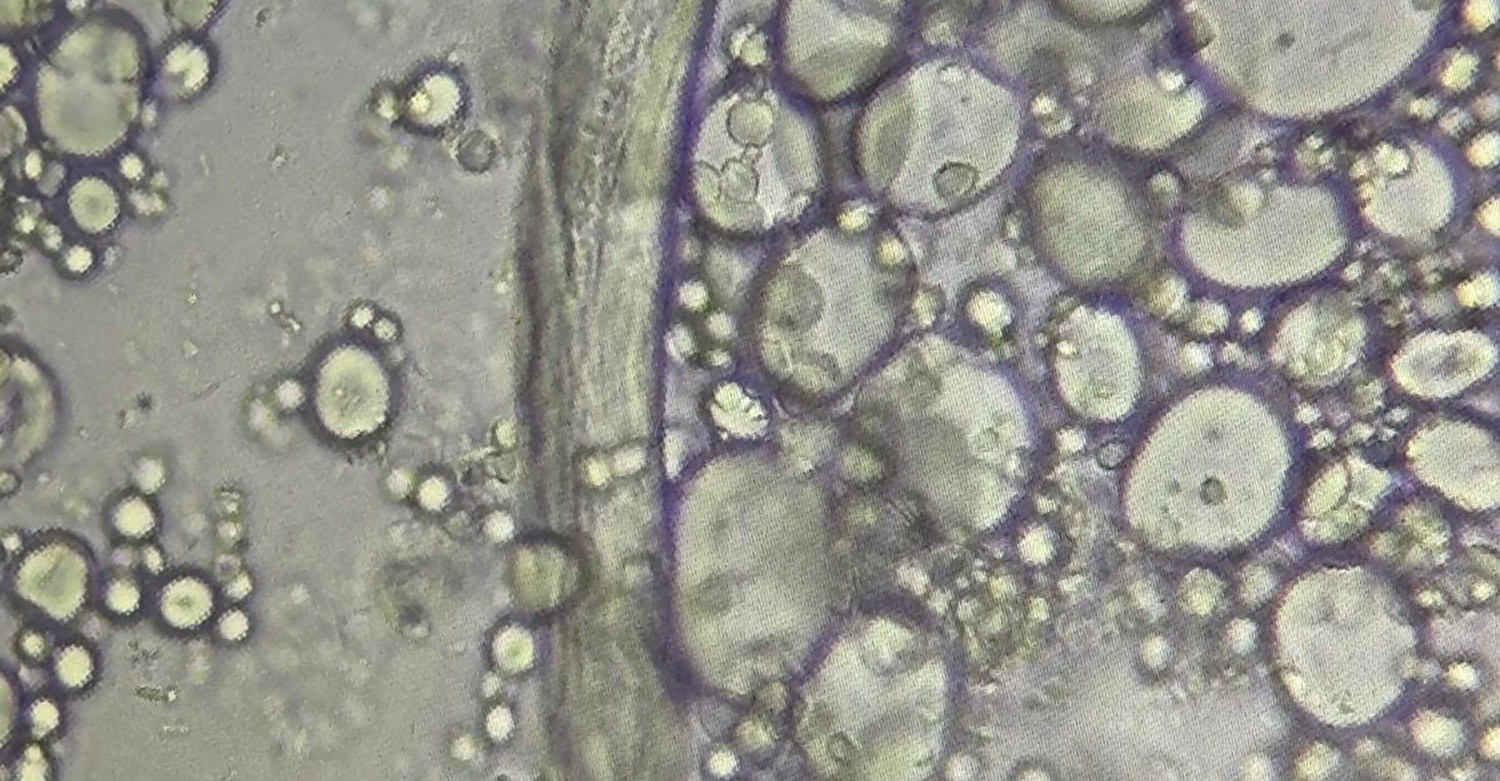

Building on In Transit, Asunción shifted focus from seeds to the microbial life within human waste, leading to the project Quorum Sensing. In collaboration with gut microbiologist Ruqaiyyah Siddiqui, she examined the social behaviors of microbial communities that inhabit our bodies and persist in fecal matter. To bring these microscopic worlds into focus, she worked with a glass blower to create an archaeological-style exhibition that magnified these invisible ecosystems. Unlike In Transit, this project materialized these themes on a larger scale, making the unseen structures of microbial life visible.

Asunción’s work proposes that we are deeply intertwined and enmeshed in the ecological networks. Our bodies are often unwitting pollinators, carrying seeds and serving as living architecture for complex microbial systems. These works challenge our perception of the boundaries between internal and external, revealing how our bodies, ecological networks, and man-made systems engage in continuous processes of digestion and transformation together.

In Transit and Quorum Sensing offers a rare encounter with invisible machines operating in our bodies, and with much of the process that we are not seeing. Stripping down the body from the seeds and microbes, we are left to draw our own conclusions about their lives. We are no longer agents, but observers of these beings. These projects render visible the systems happening in our bodies, metabolizing these ideas externally. It asks us to reimagine waste– typically unseen and dismissed once discarded, as a living entity teeming with potential.

Orla Keating-Beer:

Can you tell me a little bit about your background and where your practice is now?

Asunción Molinos Gordo:

My practice is very much grounded in biographical [ideas]. I come from a very small village in a farming region in the north of Spain, with a population of about 90. From a very early age, I developed a sense of belonging to a type of culture that is on the bridge of extinction, peasantry and farmers and rural life. Our area is getting emptied out because everybody’s moving.

I’m very interested in art as a tool for value exchange and value giving and how it has the power to reframe things. So I thought I could, in a way, instrumentalize it to share what is happening in the rural, that are very much part of the contemporary world. I think the biggest changes are happening within the smallest places.

In the beginning, I started working in a very intuitive way, just wanting to show the rest of the world what our world was like. Then it became more specific and sophisticated. When I moved to Egypt, I realized that there was this bond between Spanish farmers and Egyptian farmers that had nothing to do with the fact that we don’t speak the same language, we don’t pray to the same God, we don’t even farm in the same way. There are so many differences that should make us complete strangers, but I realized that there was this type of bond– an identity bond– because we were both farmers. It was from that moment that I started working on this idea of peasant thinking. There’s a shared culture among peasantry globally that is much stronger than the differences we have. Though of course, race operates, religion operates, privilege and power, all these things are still there. From there I started working on this idea of addressing farmers and people from rural areas as knowledge producers, not just product producers. This has been, in a way, the core of my practice. I’ve done different work that has to do with the introduction of biotechnology, the power struggles over food, bureaucracy, food trade, nomadic architecture. I never use the same media because I am very obsessed with reaching out. I work on the needs of the project itself or will choose the best medium according to how I can channel that idea in the best way. That’s why I always work with other collaborators.

I got really upset as a kid when I started studying art, and I would bring my family and my friends to the museums that I loved and they didn’t understand it. But this is my audience in a way. The art audience is easy in the sense that they’re used to being challenged by ideas. But those who haven’t gone through the roads of contemporary art, in a way they’re more demanding as an audience because they don’t take anything just because it’s art.

OKB:

You repeatedly reference this idea of Tim Norton’s “mesh” and the nature/culture divide. I’d love to hear more about this theme as it relates to In Transit. In this project, the seeds are altered as they pass through the human systems and humans act as pollinators. Do you feel that focusing on this dynamic of humans actively reshaping our landscapes can shift our understanding of our agency in ecological networks?

AMG:

The key word is agency. I think the reason why we [so often] get surprised by natural things is because we really cannot forget about the agency of life. Life just happens, it doesn’t matter if you do something or not. We think plants germinate because of us, [but they do so] because it’s their own agency and pure potential. I think that this project, for me, was a lesson of humility. We are so obsessed with action-making, thinking that we need to change the world– which we need to do– but agency is a shared thing. If there’s something that is a representation of democracy, it is the agency of living organisms.

In Transit was a project that dismantled so many boundaries, including the way the seeds entered the country. We have so many borders in our world and so many passports created to generate some type of identity or grant access to certain territories. Emirates, [especially], has very high security airports, but we are all still smuggling seeds in our guts unconsciously. Life will smuggle itself and is able to transcend all of these man-made borders in order to continue evolving and extending into other territories.

I came to this idea of the gut as lawless territory. We pay for food in the grocery store and it is ours, and then we ingest it. When it comes out, who has ownership of the food? Who has ownership of the seeds? Sure, there is probably some intellectual property of these grocery-store F1 hybrids, but what happens to the patent once it is ingested? Does it get washed away in our guts?

OKB:

I love that idea of the lawless gut. We have all these rigid ideas of borders. There’s so many rules, and the natural systems just completely erase them.

I’m also curious about the transition into the micro in Quorum Sensing, because from what I understand, it was a continuation of [In Transit] but at a very different scale. I’d love to hear about that transition and how those microbial relationships reflect and or parallel human relationships?

AMG:

Both projects started at the same treatment plant and ran alongside each other. [For Quorum Sensing] the scope was broader, because I wasn’t just looking at seeds, but at all life inside the gut. I was very much interested in seeing not only what type of life there is, but [also] the social aspect of it. For instance, imagine you are a bacteria that is comfortable living in the gut of a human, and you get extracted out and end up in a treatment plant with all of these other millions of bacterias that are unique to other bodies… How do you start that conversation? We [ended up] deciding to look exclusively at the interactions between bacteria and organisms that are very active at the human body temperature, 36 degrees Celsius. Then we took samples and took them to a lab, and I was able to play scientist.

So, the very simple conclusion was, first, that the greater the diversity of [microbiota], the healthier the body is. The second conclusion was about patterns of behavior, which have long been studied in relation to cannibalism, cheating, collaboration and many other forms. When looking at behavioral patterns, a recurring observation has been that conviviality tends to be the most common. Bacteria—probably the oldest life forms on Earth—figured out long ago that the way forward is together, not leaving anyone behind. Of course, they still [engage] in all kinds of “naughty” behavior—even mafias.

It’s sometimes easier to address political issues through other organisms. If you talk through bacteria, it’s easier to abstract and people get less defensive and can approach the subject in a less violent manner. It’s the same with seeds. I find it very useful, when talking about issues affecting us or our communities, to use this approach. Anthropologists do this all the time—they call it cultural translation, using the experiences of one group to explain the [dynamics] of another.

Who has ownership of the food? Who has ownership of the seeds? Sure, there is probably some intellectual property of these grocery-store F1 hybrids, but what happens to the patent once it is ingested? Does it get washed away in our guts?

OKB:

It feels like there’s two modes of metabolizing. There’s the mobility of the seeds and what’s going on inside the body naturally. And then you as an artist metabolize these ideas and this material outside and render them visible externally. How is visibility important in your practice?

AMG:

Visibility was extremely important to these projects from the very beginning, and I was very excited because I felt that we didn’t need to explain [much]. It wasn’t going to be an argument, it was just going to be there. I could have developed things and been seduced by the artistic part, making it more designed, [but we wanted] it to be straightforward. Everyone may think [at first] it’s like [gardens] in other art centers, it’s [a project] that may look very random. But [once you look further] it has a twist. It’s really a departure point.

OKB:

What projects are you working on now? How have they evolved from these ideas from In Transit and Quorum Sensing?

AMG:

I’ve been working on a project on common land in Spain. Common land tenancy is legal here, most of it is in the region of Galicia. There’s this very strong common community, and they invited me to do a year-long project to visualize and reevaluate the traditional practices linked with common land tenancy. So I lived there during the summer, and I learned about the complexities of the situation and decided to propose a project that was going to have outcomes. One was a legal document that was going to give them another layer of protection. The other kind of outcome of the project was fiesta, a ritualized party. Because, the ways of protecting a place, or the dynamics of a place, isn’t reliant on how many documents they produce. The thing that is extremely effective is to bring together the people on the ground and grow awareness of the culture and community that they have. So we decided to turn that document into a one day long Fiesta where we had 12 different actions to celebrate different elements recognized by the community.

There are so many ways in which metabolisms play a role [in these projects], not necessarily [the metabolisms] in our bodies, but as a network of connections. By diving into a very specific community with a very specific group of people, understanding how they work, their relationships, and [what their] values are. And then to digest it and come out with a fiesta.