In the spirit of Senegal’s ‘attaya’ tea rituals, the Attaya Hour is a series exploring unique emerging planetary education practices rooted in building locally grounded 21st century communities. Each conversation revolves around a new 21st century material culture unique to a community and location around the world (food, clothing, building or garden).

Invited guests are powerful examples of community-based leaders from around the world who are nurturing planetary pedagogies that are reinventing community-centered environmental activism. Each guest chooses their flavor of tea to kick off the conversation.

The Tea

Mae-ling Lokko:

Hello, my friend. How are you? Where are you right now and are you about to have some tea?

Mamadou Dia:

I’m fine. I’m home in Gandiol, in the same place that you last met us. And yes, you know tea is part of our universe –talking with tea, thinking with tea, having meetings with tea. It’s part of our universe.

ML:

What’s your favorite tea?

MD:

My favorite tea I think is the second tea.

ML:

You mean the second tea of attaya? Why?

MD:

Because I think that the second tea is the tea of smoothness. It’s the learning phase of deep sharing and understanding. So it represents the process of growth inside and connection, that continuity to unfold. So that’s why I like this tea because it makes this beautiful connection. The second tea links the first and third tea. The first is the most sweet, the second has less sugar, and the third is the least.

ML:

Wow. I didn’t even realize that. To me they were all very sweet.

MD:

For a lot of people they’re all sweet. But for people who live here who drink attaya all their life, they know the tea when they arrive through smell. When they have the tea, they know if it’s first, second or third. You can see it too in the color of the tea. When you see it you will know that it is the first tea with its very strong, dark color like coffee. The second is more clear and the third is clearest.

ML:

I love that and I think slowly you make me appreciate the pause in the day where we can take time to reflect on things that are happening in the community. Could you tell me about the most memorable conversation you’ve had when having attaya.

MD:

The first time that I shared attaya was with my grandfathers. In the traditional African home every day we share attaya. For our fathers, it was the moment to educate, the moment to share or the moment to fix sometimes problems in the community in our home. And in the night it is the time to share attaya with friends. During the day you are busy doing different things, but the night is time to share attaya with friends.

I recall dancing during this time, music helps in a sense to connect our thinking with our movement.

In my life, it’s been moments during attaya moments that have helped us think about how to build our community, how to create that connection. A ritual that helped bridge different generations, to really think about how they can take care of current situations and fix ongoing problems in the community. It’s been a space for us to think of local solutions to global problems. I find that attaya connects me deeply to the land in Gandiol. Each house or space where you go here, if people let you in their lives and homes, the first thing that they give you is attaya tea.

ML:

It’s interesting to think about plants and the water in tea from a place allowing us to connect deeply with the land and with each other. And I love the fact that Senegalese culture has these rituals for community building. And maybe jumping off that, if you were to describe the different types of people who are members of your community in Gandiol as well as in the region, how would you describe them? Who makes up Hahatay?

MD:

Hahatay is more than just an organization. It is a living community of young people, women, men, artists, farmers, teachers and immigrants. People who have the ability to connect land with culture and rituals. We are all united by the commitment to create a better life for everyone. At the same time we see that each person who joins, brings a fresh perspective and a unique story. So in this kind of community, you never know who just arrived, who has been there a long while, or who is the visitor because we are all part of this community.

It is a very open community and responsibilities are something we all share. There are times when I wake up in the morning, see someone, and not know the person I am sharing the breakfast with. They could have been there for two or three days in our community while I have been working in another location in the community. But when you see them you think that they are part of the community. We are constantly saying goodbye to each other, and at the same time welcoming another group. There is a constant circulation of people, ideas and cultures.

ML:

We were lucky to experience this when we visited. Has this culture of openness always been this way since the beginning, or was that something you nurtured over time?

MD:

Yeah, I think that’s something beautiful I learned early in my life in my father and grandmother’s house. When we build a place to live, we don’t build only rooms for ourselves. We build for the person who will come tomorrow. When we cook or share tea, we never cook lunch for just the members of your family. We are thinking about one or two or three people who will come at the end of a long journey. So when you do attaya you do the same thing.

You will not say that we are three, we just make attire for three people. No, you are always thinking about the people who will come. And you think about this person who will come along when you are doing attaya. People say, “when you don’t want to be alone, make attaya.”

Make attaya so that you will have friends, family, or a community around you. And it’s true. When you start doing attire, it’s the smell of tea that attracts your friends. It signals we are making attaya, we are waiting for you, you just come and join us.

This carries over to our building. We build, thinking about the person who will come tomorrow to live with us. That’s why there are more than 20 – 30 people who live here. People from very different parts of the world working together. Since I came back to Barcelona, I have invited so many people I’ve met to visit Gandiol. They in turn brought other people. For us, building community is the best way to destroy borders.

We have people from Cuba, Spain, France, Italy. I believe we are not only Senegalese people, but are part of every place that we’ve been to in life. We are from there too. Sometimes, I think that I’m Spanish because I spent a lot of time in my life in Spain, working with Spanish people, and I connected a lot with Spanish youth. Sometimes I dream and react in Spanish. So I’m part from there and here too. We can be from multiple places, we can be part of multiple communities and for me this planetary pedagogy is part of the approach of Hahatay. We embrace hands-on learning that is a circular and constantly evolving way of working, cultivating and building.

ML:

And who are you in this large community?

ML:

I see myself as a sort of facilitator and at the same time, a deep learner. I think my role is to help unlock the community’s potential while also learning from it. I love the chance to shape how people from different places can live here and develop a deep respect and interest in this community. I am a kind of dreamer.

ML:

Is there something special about Gandiol in terms of why Hahatay was able to take root and grow there and how it’s endured over the years? Could it have happened somewhere else in the world or there was something grounding about Gandiol?

MD:

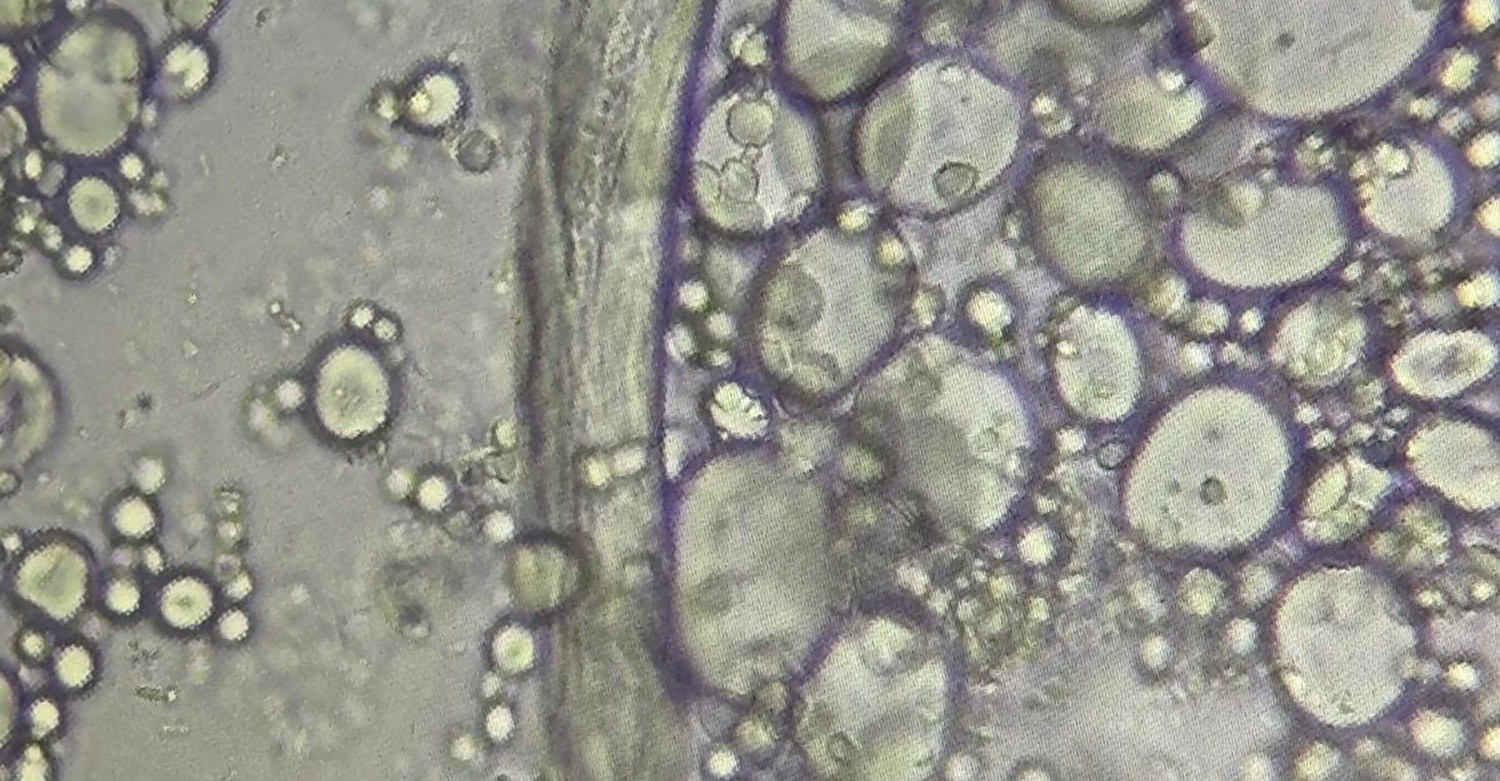

Gandiol is a very interesting place with a rich story. But it is a land full of present challenges. It’s where the river meets the ocean. So it teaches us about adaptation and perseverance.

But it is a land of love too because in this union of the river and the ocean, mystical things happen. We have our own weather, when you are in Gandiol you can feel it, you can smell it. There is a deep sense of belonging and the strength to endure. So people from here are very different- they are part of the sea, they are fishermen but they are also part of the land, they are farmers.

So there are a lot of big dreamers here because this land, a lot of beautiful things have happened. For us is a gift to be born here, to be here and to create a space for sharing this with communities around the world.

ML:

I’m wondering because of this unique climatic relationship to land and water, is there something unique in the way that you look at land ownership and management that has underpinned the way your community has grown? How do you care for land?

MD:

At the beginning when I came back home and I was thinking about how to start this, not many people believed in our vision. For us it was very, very difficult at the beginning. But little by little I think that the work that we started doing with young people and with women became very interesting.

These were the things that gave the community trust in our approach. They saw how we stayed put, working, thinking and creating with them ways to solve the problems and challenges that they were facing in their own land. And little by little, they began to help us access land and build new projects.

If you remember when you visited, there was a building project called “Tabarnete”. This land was a huge area and it was majeure of the community that said, “you can go there and build your projects.” They saw that we were building a cultural center, artist residency, schools for kids and they began to see our organization as part of the community.

It is the very people in the community with whom we build our projects. And I find that this approach very interesting, that you know the person who you are working with. Sometimes in organization, we think in numbers –we are 5,000 or 1000 people.

But for me when I came back to Senegal, the interesting thing became who was I working with, what family did this person belong to, what is our relationship? For me it was very, very important because my approach was to look at how we can address global challenges with a local approach.

At the same time when we look at the way we want to build something, the first thing is with what materials will build it, where this material will come from. The first step is to ask, “what do we have here and what can we do with what we have here?”. So that’s why we built our first school building with plastic bottles dumped in the river. We went, collected them and built our first school center.

Gandiol is a place that has a lot of land. There is more land than people. When I was in Spain and shared for the first time the idea of coming back, people laughed at me, asking me “wow Mamadou, why on earth would you want to go back to Senegal, there’s nothing there.”

ML:

I mean it’s interesting when people say there’s nothing in Gandiol. This maybe speaks to what we value. And I want to get to this because I think your pedagogy around building with earth and plants is also something that has generated a unique approach to building. But before we do, can you say a little bit more about the land ownership structure there? Is it through chiefs or there’s a matrilineal line of women in control of land?

MD:

Yeah, there are different situations. There’s some land that is allocated for women in the community and there is land that is for the community. It is majeure of the community who can give their land to organizations who want to build something in the community. There’s a lot of land that our grandfathers used for agriculture but now there is not a lot of land for farming close to us.

I think that our approach to land ownership has been very diverse. For the artist residency, we bought it from a man who lives nearby. For the cultural center it was a land for a farmer. And the third space was given by the majeure.

Now, however, I think that land will be difficult to acquire because close to Gandoil, petroleum was recently discovered.

So that’s why for us communication and cultural action is very important to protect this land. We now have resources, we are on the map. Before couldn’t Gandiol on the map. Having a radio station in our space, gives the community a platform to communicate, to develop conversations and to defend their values.

ML:

Are there legal frameworks to protect the land as a communal trust in Senegal? So that land can never be used for commercial or industrial activities. I don’t know if there are legal frameworks for that to happen to protect land there.

MD:

Yeah, there is a framework for this. Gandoil has a lot of natural parks protected by the law and this helps us with the protections. There’s a lot of land allocated to the national park for birds, animals as it is a natural reserve. There’s a lot of spaces of animals that you can see in Gandiol. It’s very, very normal to hear the waves of the sea and birdsong. But for me that’s something very important that we have to protect and preserve because it’s essential to our welfare.

ML:

So in the same way we have mechanisms to protect other animals in our ecology, there are ways to also protect our culture. So you described a little bit about your planetary pedagogy in terms of building with what is available in a place. And I wonder if you can talk about the process of how you’ve learned over time to build with materials like plastics and earth. Did you learn this growing up or have you had to rediscover things that you learned as a child or has it always been a process of learning onsite? And how have you managed to develop that into your own way of teaching?

MD:

I think that I’ve been lucky to learn from traveling and discovering different communities. I remember the first time I was in Colombia in Palenque. I was inspired by how they built their house with clay, in the sun. When I came back to Senegal, I began to look deeper into how potters build with clay and sand. It was amazing, it got me looking into building traditions in Burkina Faso from Mali. I saw that in such contexts, preserving nature is part of their pride, rituals, and ways of living. When I came back home, I decided that my religion would be how to live this way in my day-to-day life. That became my own way of learning in the university of life and learning through doing. In our universities, who they include in their approach of caring and protecting the environment are too expensive. Often they make a business out of things that should be free. Outputs are then not accessible to a lot of people.

Attaya Round 2: Hahatay’s Planetary Pedagogy

ML:

In terms of how you’re also creating your own educational system, do you see your unique way of educating anyone who joins your community as different? Is this different than what you’ve seen happening in formal school systems like you’re describing?

MD:

Yes, I see a very big difference. Often, people who come to visit us from schools, they often want to change lots of things. They typically say to us, “if you want to do this you have to do this”.

To which I say, “no, there’s a lot of ways to do things. There’s not only one way. There’s a lot of ways to do things. There are a lot of ways to protect nature. There are a lot of ways to grow, to make yourself resilient and to do work in the community.”

But we need time to let them learn in their own way– learning by doing, learning by asking, learning by making mistakes. It’s very important that people make mistakes. Don’t be afraid to make mistakes because we think that it’s part of our journey. But typically when people come from formal academic systems, they are very afraid to make mistakes. You are all the time in the “comparative” or in a sort of competition. So you must be the best, you must be “more and more and more…”

It’s not shocking that our world is the way it is. People aren’t thinking enough about collaboration, or how to complete or unite an idea. We are all the time thinking about ourselves or myself. This constant I have to. In the midst of this, we lose the opportunity to belong to a community and to let people from different communities help us.

At Hahatay, we think that an approach for planetary pedagogy is based on being at the same time a student and a master. It’s the same thing, this cycle of learning and teaching again and again.

In the process of learning to teach, you sometimes forget that role. You become an eternal learner. This approach is shaped by experience of migration, community engagement and the necessity to find local solutions. We believe that education that emerges from direct contact with the earth and the people around us transcends textbook-learning and develops knowledge that can be applied in everyday life.

ML:

I think that this dual nature of being a learner and a teacher is a good way of nurturing a flexible practice of adapting to the challenges that we continue to face over time.

Formally there seems to be a system that you have developed in terms of working with earth, textiles, recycling plastics and animal farming. As your community members have built up knowledge in terms of how to do things, how do they teach newcomers? Because I felt like there is a system that is probably not as loose as you’re describing right now. To take twelve students from very different contexts and immerse in the broad range of things that you do seems to have a system. In your mind, even if it changes over time, what is that system?

MD:

We want to be eternal students. Sharing the things that we have learnt is a good way to actually process that learning. So sharing is a good way to refresh that knowledge. So when we are with a new person who has joined our community, I say that you don’t have to teach them anything, you just have to learn… close to him or her.

And when a person sees the connection that you have with the plant or building or animal, that person will recognize a teacher in their life and hopefully inspire them to work with you. I remember when you were here and we visited the farm, the first time that the sheep came to us, all the students were afraid, jumping around a little in fear.

But when they see the relationship that Asan, the head of the farm, had with the animals, everything changed. So when people see you, your ability, or the way you connect with things, observe the love, patience and presence that you have–be in with animals, plants, land, and the bigger ecosystem around you, they learn better. They connect better with these things and you will see yourself as just an facilitator to open to unlock the connection between this new person and this new thing.

And I think that being a facilitator is just the thing that we have to do. We have to unlock this connection in the way we teach. When you want to teach someone, you can sometimes cut this connection. But if your way of teaching is rooted in creating a deep connection with material and the things in front of you, I think that relationship can unlock a new connection between new material and a new student.

ML:

That’s beautiful and probably opens up a whole new perspective in terms of the psychology of teaching where you eliminate hierarchy and become focused on showing, demonstrating what you’re doing as a form of education. And so that idea of immersion is very profound in the way you’re describing it. In the past you’ve partnered with many educational institutions that have visited you. And I’m just wondering over time have there been partnerships that have been successful or failed? Are there examples that stand out in terms of how we should not be doing things or actually this is the model.

Attaya Round 3: The Human Project

MD:

You know what, yes. Since the beginning there’s a lot of schools, programs, organizations, institutions who come to share with us and with each one you learn a lot of things. In general, people who come from Europe or Western cultures, are preoccupied with finishing something. For them, it’s very important to finish something.

But for us it’s not important to finish something. For us it is important to preserve the process of things. So sometimes people get very angry or stressed because we have to finish the construction of the school or we have to finish the process that we started. Maybe before they came, there is something inside them that tells them to finish something, take a picture and share it on Instagram.

And for us in the areas that we are learning, we see that finishing a project is not very important because our space is really a space for exercising our way to learn, exercising our way to connect, and our way to build community. The process is human, not physical. It is not to finish something but how we build ourselves. When we build spaces, the space is just an exercise, an excuse. What we want to build is inside us, our values, our connections to things, our connections to another. That is what we are building.

This can be very deep because those who come to visit us are looking for the same things. They are looking at how to grow their humanity and expand their perspective of life. Others come just to share photos, to say that they are in Africa and working with a community. They don’t make this journey for themselves, they make the journey for the media. You can tell the difference. I’m not saying either bad or good, but it’s interesting because we learn something in each.

ML:

Haha, interesting indeed. I wonder, before we wrap up, if you could describe the world you’ve built at Hahatay. What are the sites, buildings and programs that you have going on and ultimately how do you want to grow in the future in terms of other programs? Do you want to expand in Gandiol?

MD:

Building community is part of the need to build ourselves –a way of resilience, in a way of preserving nature and ecosystem. We can build a strong and beautiful community. So in Gandiol, we are still working on this. Last year we built two new centers in St. Louis and it’s the same project of building the human. The crises we are experiencing are human crises, so we must fix the underlying human values if we want to address climate change and aggression or criminality.

We are living in a difficult moment and we must work on how to build humanity. Maybe it will be still in, maybe in Saint Louis, maybe in South America, maybe in the United States, maybe in Ghana when you invite us there. We are thinking about it, we are thinking about creating spaces and sharing time because we think that is the most powerful thing that we have.

ML:

I think in the way that you talk about the work and I’ve consistently been asking you what are the systems, what are the assets, what are the programs? And it’s very clear in your philosophy that they’re not as important as the human project. Those are the byproducts, but there’s a larger project which probably will never end. Last question because you mentioned time is about rituals. As a species, we’ve tended to mark our growth with rituals, whether it’s a seasonal, daily, yearly practice. What are some of the rituals that you’ve sustained over time in terms of rituals that you do as a community?

MD:

We do a lot of celebrations with the community –for example before the rain season happens, we share a beautiful party to connect, sing or dance for a good rain season because it is the time to plant. Seeding is the time to connect with the earth.

Another ritual that we celebrate is the ritual of the sea and the river. We have a god called Mame Coumba Bang. She is a woman spirit who protects the sea and river. It’s beautiful when the fishing community goes to the river and performs the ritual where they go to feed her and her family. In doing so, they ask for the same protection of their families who rely on the fish and fishing livelihoods. They offer so their communities don’t lose their life in the water and also have the possibility to feed their family from the opportunity in the water.

That’s why people from Gandiol and Saint Louis have a very deep connection with water. I remember when I was looking for a way to go to Europe. When I applied twice and didn’t get a visa, I decided to take a boat to crossed the ocean and go to Europe. I remember on this journey my conversation with the sea. I thanked her for feeding all the generations of my family–my grandfathers, my fathers, my mothers. I thanked it for giving me the opportunity to have good study because the money that my mother earned to pay for my study, came from the sea.

I asked her at the same time, to protect me and give me a good trip to discover other places in the world. And it is the same connection I had eight years later when my journey in Europe was finished. I was in the front of the sea thinking about a name for this organization, when the term “Hahatay” came to me. I wanted a name that connected me with my life, my journey and my future too.

ML:

What does ‘hahatay’ mean?

MD:

It means joy, a deep joy. It can also mean “dancing with joy” or “laughing with joy”. It’s the feeling of being so free, you can laugh without fear, restraint or balance. That’s when you are making ‘hahatay’.

ML:

What a beautiful note to end on. Thank you, and I’ll see you in Gandiol soon.

MD:

Thank you. It has been a beautiful conversation to share.