In the spirit of Senegal’s ‘attaya’ tea rituals, the Attaya Hour is a series exploring unique emerging planetary education practices rooted in building locally grounded 21st century communities. Each conversation revolves around a new 21st century material culture unique to a community and location around the world (food, clothing, building or garden).

Invited guests are powerful examples of community-based leaders from around the world who are nurturing planetary pedagogies that are reinventing community-centered environmental activism. Each guest chooses their flavor of tea to kick off the conversation.

The Tea

Mae-ling Lokko:

Hi LinYee! I’m glad you already have your tea in hand. Where are you and can you tell us about the tea that you’re drinking?

LinYee Yuan:

I’m in my home office, a converted closet in my home in Brooklyn in unceded LenapeHoking. When it starts to get cold, I switch to drinking PG Tips out of my giant Helen Levi mug in the mornings. I put a little bit of honey, some Diaspora Company chai mix and some milk.It’s a little bit of a high-low mix with the PG Tips and the fancy small batch, single origin spices in the chai. What about you?

ML:

In the mornings I will typically have black tea. I have some lovely tea from a research farm in the Azores that I visited last week. And at night I’ll have some kind of herbal tea. Ginger always gets me ready for bed! So how have things been going on with you? What are you working on?

LY:

Well, this is a very transitional moment. I always joke that my year ends after Halloween because basically Halloween is the height of our New Yorkness. We have an epic Halloween and then there’s the New York City marathon that happens the Sunday after Halloween. We have rituals around that. And then basically it’s the end of the year already. I’m thinking a lot about what’s coming up next in 2025 for Field Meridians. We are also about to start a new cycle of programming, which is about gathering our community. Our Nature School programming over the spring and fall seasons was a siren’s call for people who have like-minded values and interests. And now that it’s winter–a time of rest, we’re going to be gathering weekly at my favorite bar, Rodeo.

It’ll be an informal gathering where we’ll read a grounding political text together, and break out into working groups to start putting together a plan for how to plant our food forest in Crown Heights. I’ve never done this kind of facilitation before. I have probably less knowledge about forest garden systems than people who will show up to do this work together. But I’m really excited about seeing how it unfolds. And I think the older I’ve gotten, the less entwined I am with corporate mentality or capitalist systems of production. I just embrace the unknown and the kind of ways that things will just unfold. I think I have a much deeper appreciation and understanding that that’s kind of the nature of things, and I feel less inclined to control the entire narrative or the product. I just am excited about holding a shape for things to happen.

ML:

Wow. It takes a lot of concerted deprogramming to embrace that. How has this happened for you? Has it been based on your experience with how communities function? Or has it been through realizing that that way of working in the corporate world is not as impactful, effective or a combination of both?

LY:

I would say it started with MOLD. Over the course of 10 years, I’ve been confronted with questions around how do you productize MOLD? How do you monetize MOLD? Early on, I just realized that I am not a salesperson and I wanted to reserve my capacity for work and thinking for the making of the magazine.

So I let go of trying to pin down a business model for MOLD. It feels really foolish to say this now, like a decade later, but it’s always been pro bono, where I will make money and just spend it on MOLD.

It has allowed me incredible editorial freedom. I’m really proud of the work that we’ve done over the past decade. What it also has taught me is that when you untether yourself from business models, then you can do things on a timeline that happen naturally.

I’m a “type A” person. I’m very controlling in some ways, and so I like structure. I like working in a group structure with weekly meetings and things like that. But I’m also not going to stress if a collaborator doesn’t deliver something on time because we don’t have to publish on someone else’s timeline. We can publish on our own timeline. I have learned that things come out when they’re supposed to.

Even with our very first print issue, I was in tears and it felt like a biblical level of stress that I had put myself under to deliver the first print issue on a certain timeline. And I spoke to my partner and he was like, you’re the only one who is holding on to this timeline. It was an awakening for me, and it took me many more issues of MOLD to let that go. But now I can say a decade later that yes, time and time again, things come out when they’re supposed to come out. I have allowed myself to really trust in this idea of “community time”.

Attaya Round 1: The Beginning of Field Meridians

ML:

That’s beautiful and hard to unlearn and cultivate. I wonder if we can talk about that. You talked about community time. Can you begin by introducing us to the different communities you’re part of?

LY:

I am a first generation Chinese American. I grew up in Houston, moved to New York when I was 18 for college and I’ve lived in New York now for over 25 years. I always talk about New York as my spiritual home because New York is one of the few places that I have been where I feel like I can just be. I don’t have to be an Asian American woman or someone’s mom or someone’s wife or whatever it is, whatever labels people like to put on other people. I have lived in Crown Heights, which is in central Brooklyn, for 15 years now. I lived in Bed-Stuy for six years before that. Essentially I’ve lived within this one mile radius community for over 20 years.

MOLD started in 2013. That community is really a global community of people who are interested in thinking more deeply about our relationship with food. I would say there’s students, food industry folks, artists, farmers, and designers who are part of that larger community. It’s a community that we’ve really cultivated through consistency over the past decade.

But we don’t really do events. We’re not really out there in the world but we’ve done more of that this year. We did a little bit of it pre-pandemic, but I always had this idea that if we could gather people who read MOLD into a single room, there would be a lot of magic that could happen.

I was thinking about what I wanted to do, once we finished our six issue cycle of the print magazine. During the George Floyd Uprisings and Black Lives Matter movement, I realized that the work I wanted to engage with was rooted here in my neighborhood and with my neighbors. I wanted to think about how Crown Heights, ie. me working hand in hand with my neighbors, could create new models for food sovereignty here in the city.

Field Meridians came out of this question. What would the future of food look like in Crown Heights? Over the past two years, it has unfolded in this way where there are so many intersecting uncertainties in our moment. The pitch for Field Meridians is “an artist collective that’s interested in creating tools for ecological resilience”. At the heart of this ecological resilience is knowing your neighbors. It’s such a simple thing. It’s something that should be so ingrained in us, but our cultural and social modes of production today really don’t encourage knowing your neighbors.

I would say because I have lived here for 15 years, I have seen the rapid gentrification of our neighborhood. I’ve seen an influx of young people who moved to the neighborhood. A lot of them walk around with headphones in their ears, and totally zoned out. They could be anywhere in the world. And that energy is just not it. We should actively be saying good morning to people as we walk down the street. Something so simple is the thing that’s going to help us better understand the challenges of the moment and then better rise up together to meet those challenges.

ML:

I mean this question of resilience gets back to the strength of our networks as we enter these multiple crises? It’s as much a form of social security and as it is ensuring a quality of life that is enriched by these relationships. How do you see yourself now within these communities?

LY:

When I moved into this community in Crown Heights, I was 30, I was single. I was still very much entangled in a lifestyle of my twenties, which was very invested in downtown New York. I partied a lot. I was very much part of the nightlife of downtown New York. I did try to be a good neighbor, I basically only knew my immediate neighbors around me.

Fast forward to the end of that decade, I got married, I had a child, the pandemic happened, and my neighbors started organizing against a proposed development that was happening on our block. And that experience really catalyzed something inside of me. I realized in that very isolated moment that this work of organizing my neighbors was deeply connected to who I am.

I was a student organizer in college, I guess have always been, in some ways, an organizer of people. I threw a lot of club nights and hosted a lot of house parties in my twenties and thirties.This mode of being a wrangler of humans was very much in my DNA. And I also realized in that moment of organizing with my neighbors against this development, that there was so much joy to be had in just seeing people who I wouldn’t normally socialize with otherwise. I often didn’t know what people did professionally, but we shared a common issue that had catalyzed all of us. And now these were my comrades. That experience was very transformational. Many of those same people who were core to that fight against the development are still very much in my circle. They are part of the work that we’re doing now and are mentoring me and teaching me how to do this work. I very much feel thankful for that. Now I am a person who goes to my community board meetings. I am a person who is part of our newly formed block association. And I think that most importantly, I’m a person who I hope is a good role model for my children around the critical importance of knowing your neighbors.

Attaya Round 2: The Nature School

ML:

So how did you manage to draw the level of neighbors and participation that we’ve seen in your programming for Field Meridians? I understand its beginnings began with the threat of a development in the neighborhood, but how has this changed in the last year?

LY:

So I’ve never worked in a nonprofit and or for an arts organization. I really came into this space in a very naive way. I’m still approaching it in a very naive way. I thought about Field Meridians through the lens of the type of media I wanted to produce. I have worked in media my entire career and it’s the language that I know best. And so I understood that I want to produce site-specific work. I want to publish and I want to broadcast. I want music back in my life. And so those were the three stakes I put into the ground for the shape of Field Meridians—publication, broadcast and site-specific works.

Our first project was a week-long program in our park. I worked with the designer Lily Saporta-Tagiuri and we built a mobile kitchen that was anchored around a solar oven and other forms of solar cooking. We set it up and offered free, artist-led, public programming for a week during the summer solstice in 2022. That project was a provocation to ask our neighbors what the future of food should look like. So many people use that park. And so many people were like, “what are you guys doing?” It was such a strange thing to see this giant satellite dish looking thing set up in the middle of the park, and then people were cooking on it. It instigated so many interesting conversations and story sharing!

We had such a diverse range of opinions, incredible ideas, and moments of connection, that bloomed from that project.

The Nature School came out of this idea I had in 2023, which was that we should have a nature center in Crown Heights. Sometimes when school was out, I would take my kids to a little nature center upstate. It’s like an hour and a half away. We walk around this lake and there’s animals and it’s very sweet, it’s very beautiful. It’s community supported. You can go birding. And I just loved how educational it is, and also how it really tells you about the place you’re in. I thought this would be such a beautiful offering in our neighborhood.

So as I started speaking to collaborators and mentors and people who were just kind of in my ideas world. My friend Helen was like, well, why do you need a place? You can just start doing this programming you want, but have it in many different places in the neighborhood. And she was 100% correct. That was absolutely the approach to take, and it did the work that I wanted it to do, which was to find like-minded people who are interested in ecology and creative practice, in understanding contextually where we are, and also people who are really interested in this form of community building and investing in a certain living infrastructure.

We have produced over 60 artist-facilitated programs over the course of the year, most which have been oversubscribed, which is great because they’re quite intimate in scale. Each program typically hosts 15 to 30 people.. We’ve had over 2000 participants in the Nature School over the past year. It’s been an incredibly centering experience for me. I’ve been lucky enough to have been able to attend most of the programs.

I feel very grounded by it, and I hope that people who participate experience that same feeling because there is this foundational sense of curiosity and it brings everyone together. We’re all learning something new together. There’s a sense of openness that happens because the artist facilitators are sharing knowledge as an offering.

ML:

When you say offering, do you mean a pedagogical approach to learning about nature or the world around them?

LY:

Absolutely. Most of our artist facilitators ground us in some sort of reading, in some sort of visioning, in a sort of narrative that allows us to be with them on their own learning journey. In some ways, the workshops are just one moment in the artist’s creative practice that it feels very generative.

ML:

Yeah, absolutely.

LY:

It’s like when you’re giving someone something—there is a feeling of exchange.

ML:

Having myself run one of the workshops, I wonder how you see the role of the facilitator. In order to facilitate, you have to bring these activating materials or readings or just some type of media that draws people in and opens up a range of participation, which it’s not an easy thing to do in a productive way. And I wonder if you’re reflecting back on some of these sessions, workshops, walks, what were some of the skills or tactics or really interesting approaches that you started to see among your facilitators and collaborators?

LY:

There’s an underlying generosity that I think cements all of the programming together because all the artist facilitators are offering a pedagogical tactic. I would say some of the themes that have emerged have been a deep sense of alternate ways of knowing, a deep sense of noticing.

There’s also this idea of training your attention, whether that’s through meditation or through the practice itself. It really is a moment to be present in the real world. I think one of the greatest examples of this is birding. One of our facilitators, Indigo Goodson-Fields, is an incredible poet, birder and writer. She’s been leading monthly bird walks with us, and I had never been birding before. She’s my primary interlocutor with the birds, and it was a transformative experience. Now I bring binoculars everywhere I go when I travel.

I’m that person now. It’s such an incredible experience to see, hear, and witness these birds doing their thing. And it really reminds you that, again, we are guests in this land. This is not a place to be owned. It’s a place to visit. We are here by the grace of other things. And so that is one thing.

Another monthly program is Michael Cafiero, who’s a landscape architect. He lives in Bed-Stuy. He’s been leading street tree walks and tree walks in the park. That has also been a transformative thing for me because prior to this year, I don’t think I have really thought that much about the trees of New York. We had an incredibly hot summer and now we had a very dry fall. And this year I have cultivated a deep, deep sense of gratitude for the trees that share this place with us. It’s pretty incredible the work that they do. And so that’s another thing that I most look forward to hearing about why certain trees are planted in New York.

What are the qualities that urban planners look for in trees? The reason why certain trees were planted in certain places is that some are planted for beauty, others for resilience. I mean, all the street trees in New York are very resilient, but some of them are genuinely planted for the light quality that they bring, which is so poetic and so beautiful. And I’m so thankful for the urban planners who think about the world in this way.

Every program offers a different entry point into noticing really. That’s really it. I think a lot about how I spent the summer in Seattle with my kids. I had this premonition last year that I needed to spend some time out there. I have cousins there, two of my best friends are from there. And so I spent six weeks with my kids outside . And I came back and it was a really hard adjustment for me, and I think also for my kids.

I was trying to find the language for why I was having such a hard time adjusting back to the pace of New York. And people were like, oh, is it because you want to move to Seattle? I was like, no, absolutely not interested in moving to Seattle. But there’s something about the way that we navigate the city versus how we were living in Seattle. I realized that when we were in Seattle, at the national parks, or even in the local parks and swimming in the lake, this experience really asked us to tune into the world that was around us: the birds, the pebbles, the temperature of the water. My son, who’s five, spent the entire summer asking, “can I go touch the water?, can I go in the water?” And we’d be like, “yeah, sure!” But when we came back to New York, he’s like, “can I go in the water?” And I was like, “do not touch the water.”

And so in New York, the city is built in a way that’s like, do not touch. Instead of tuning in, New York asks us to tune out. We learn to not notice the sirens, not notice the surveillance helicopters, not touch the subway pole, not to sit here. And it’s just a totally different way of moving. I realized that invitation to touch was so important for the Nature School.Once a week, for an hour and a half or two hours, you’re being invited to tune in to a very safe kind of controlled space that is being held specifically for the purpose of tuning in. That is a form of meditation.

ML:

I can totally relate to this. In terms of the workshops or the activities that you’ve done, what have been the strategies for forming new senses of community between participants? What have you seen as successful or not so successful in terms of building relationships between the people who come to your courses, between people who teach these workshops? Does Field Meridians have a role beyond the workshop in terms of formulating and cultivating community?

LY:

We are still in process. And that’s been a question, what happens beyond the workshop? We have the curriculum format, which is something around that is intentional. We started the Nature School knowing that every workshop would then have a curriculum that would be part of it. The idea is that if you’re moved by that workshop or interested in it, you could download the curriculum and then replicate some part of that program within your own local context. It’s a form of pollination. I realized how deeply people wanted to connect after the workshop. One of the big questions I’ve had over the past year has been, what should be the format for this? We have had suggestions to use WhatsApp, Discord, Google Groups, all the usual suspects. And then two friends—Radhika Sharma who facilitated a meditation workshop that was based on the elements in the spring, and Geneva White, a brilliant strategist and leader who runs a talent development program connecting BIPOC youth to creative opportunities—suggested doing in-person events. Geneva was like, you have all of these mentors and organizations that are already rooted in Crown Heights, you should look at how they organize people and move the work forward and think about those models. And she was 100%.

That advice led to this winter structure of a weekly meeting of readings and also actually doing the work because that is the way our community board is structured. I mean, they don’t do weekly meetings, but it’s a monthly meeting. And then there’s smaller committees that are set up that oversee specific aspects of our community. This is a tried and true playbook that serves our community in the moment. It’s something that’s recognizable for many different types of people, different generations, and it does what it’s supposed to do, which is to protect our community and give our voice to the community. So for all those reasons, that’s the next format for Field Meridians.

ML:

There’s the contrast of fluid, loose nature of people coming together around thematic, mobile events happening in your living room or walking around the neighborhood versus a structured meeting in a specific place. Do you think that ultimately the format you’ve been running that has brought 2000 people together in the first iteration of the Nature school is something that’s not necessarily sustainable?

LY:

When you say sustainable, what do you mean?

ML:

Can you keep running it in the way that you had been in terms of time and your resources and people’s availability so that it has the capacity to be continued for a period of time? But it also might have to do with a question when you’re asking around how long does this need to last? Because maybe it has a role in bringing people together in the near term in order to transition into something that’s more weekly, for example.

Attaya Round 2: The Food Forest and Food Sovereignty

LY:

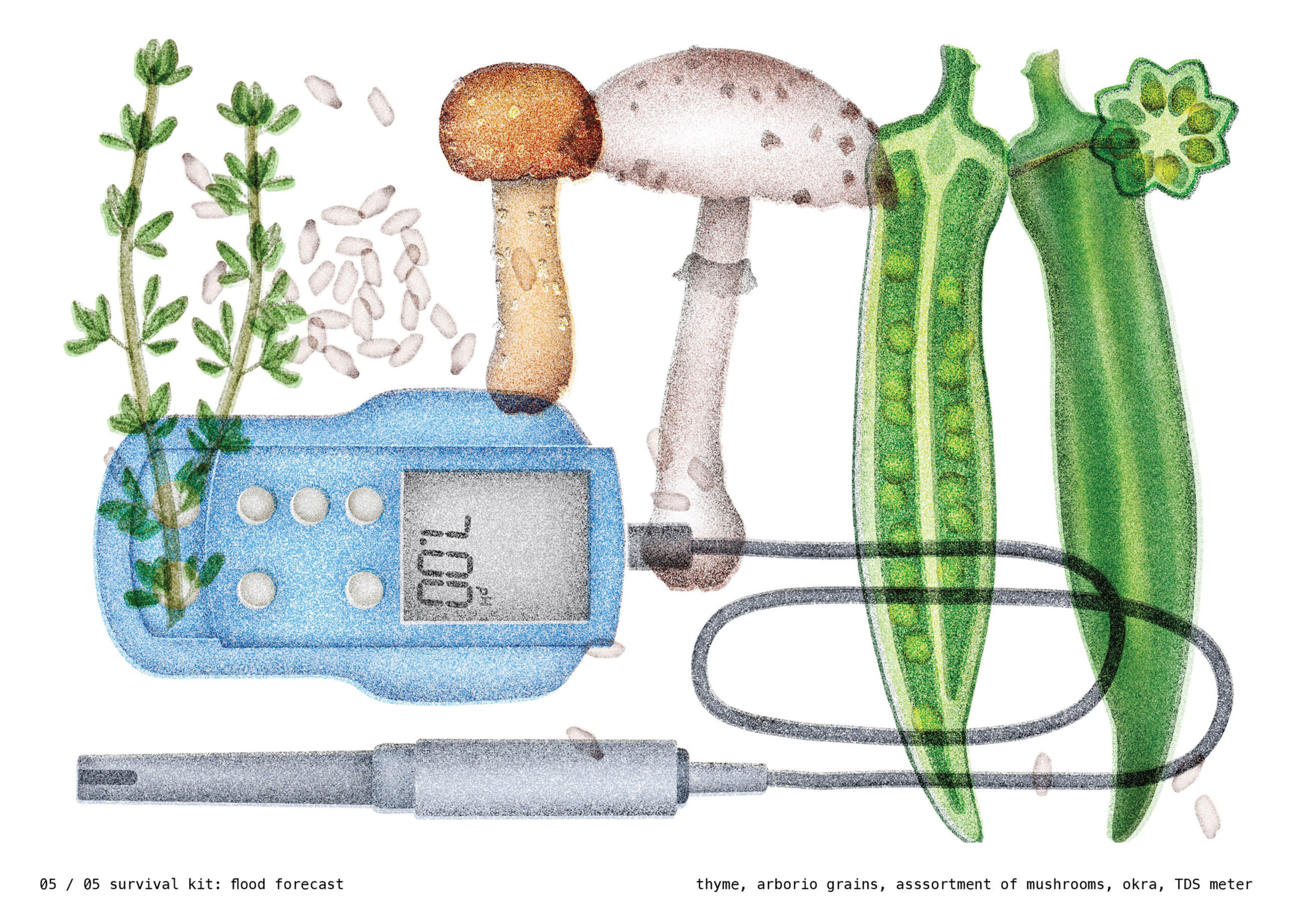

For me, the larger vision is food sovereignty. My immediate, short-term goal for that is the food forest, because that brings together so many different threads of my personal practice: ecology, place, food, educational programming. And so the Nature School was this kind of beacon.

The other thing that MOLD has taught me is that there’s a season for everything. And what I understand about our current fixation on scalability is that these are modes of capitalism that are unsustainable by nature.

Who is it for? For me, Film Meridians is a collective and an art practice where we collectively create living infrastructure or as Beuys called it, social sculpture. The Nature School is really just one tool for that work. Each season, the Nature School ends, and we’re like, do we do it again? Maybe? And I am interested in the ways that these smaller programs and smaller iterations carve new paths towards the forest.

Will it happen forever? No, for sure not. But I think for better or for worse, this is just the shape of the work at this moment.

I’ve published MOLD for over a decade, and the shape and format of that work has been the same from the beginning. We’ve always published on WordPress. I mean, it was really just me first. So I was always published on WordPress. I always knew I wanted to make a magazine. I’ve made magazines my entire career. So these things were fixed in a lot of ways. When I was saying that the success of that work is about consistency, we’ve published a story on MOLD at least weekly, and up to three times a week, for the past decade.

Field Meridians is totally different–it’s free jazz. We’re going to have people pop in when they can pop out when they can’t. And that’s the thing I learned from the organizing we did against the development, is that in these kinds of living structures of neighbors, life happens. So someone’s going to be up in it, leading it at every meeting, doing the work, and then something’s going to happen, and then they’re going to drop, and then somebody else is going to pick up the baton and keep going, and the shape changes. But ultimately, if we’re all kind of moving toward the same horizon, we’ll get there.

ML:

I love this is in service of a bigger vision –the food forest. And that there are all these other things that need the time and practice to activate and build in terms of relationships and infrastructures. How do you think The Nature School is different from formal education in terms of timelines, in terms of thematic, in terms of skills, in the ways that you’re seeing it emerge now?

LY:

I mean, formal education in the United States is a handmaiden to capitalism. It’s structured in timelines that are about delivering, meeting specific standards. It’s about training human curiosity into a very narrow channel so that you can be a cog in a machine.

Now, these informal educational opportunities that we have presented through Nature School, I would say are the exact opposite because we don’t have a goal. There’s no delivery at the end of this thing. There’s a moment where we share work in progress ideas. It’s not about selling the thing. It’s really about the relationships that are formed laterally within that two hour window of programming. It’s about having an open-ended conversation. It’s about a worldview in a lot of ways. It’s about world building in a lot of ways. It is about shattering some of the preconceived notions about what education is and re-embracing education as a kind of pool for curiosity, a site for inquiry, a place to just wonder about the world; to dream a little bit.

I think that that has been the biggest success for the Nature School, is to be able to hold space for that in a way that’s nonjudgmental, supporting,

Hopefully people will bring things into their practices. I feel like we won’t know the true impact of the Nature School probably for years to come, if it had any impact at all. I have no idea. We will see. But my hope is that people have made friends and learned something –a way of looking at the world that may have unlocked something else in their mind.

From a personal perspective, I can say that that is true. We had a lichen walk with Mustafa Saifuddin, who is a microbiologist. He led a lichen walk in the parking lot at the Brooklyn Museum in the spring. That lichen walk and Mustafa’s way of looking at the world just totally blew my mind. Lichen have so many lessons to teach us. They’re world builders. Even their existence breaks classification because they’re both microbe, algae and fungi. They’re all the things! Lichen are uncategorizable. Arguably, they don’t die because they just go to sleep for a hundred years and then come back alive because of their community. My hope is that Field Meridians can operate in some ways, like these unclassifiable lichen communities where we’re persistent, we show up, and when some pieces of it fall off or die off, it makes room for new things to emerge. And so I’m kind of interested in that way of expanding into other places and niches and ideas.

ML:

Admittedly, I am a person deeply entrenched in the elite academic institutions. My father’s way in the world was paved by educational institutions when his country was still a colony. Those institutions enabled mobility for a young Ghanaian boy in capitalist Britain. So historically, I cannot underestimate that power given where I am from.

But today it seems we are in this transition period where grassroots level, social media, open source tech, etc are shifting the cultural capital and economic capital once accessible in educational systems. I wonder if you see opportunities for partnering with formal academic institutions. Do you see areas of opportunity, and if so, have you thought of any ways that it could be a synergistic collaboration in this transitory period?

LY:

Palestine has taught us so much, and I think that what has happened in the last year has really cracked open the truth about higher education in the United States, which is that it is not a place for free thought or for ideas anymore. That in many ways the model for academia and the way that it is privatized in the United States is fully entrenched in the upholding of systems that no longer serve us. And I have gratitude for academia because I could not do the work that I’m doing today without the academic grounding that I received at Columbia. That’s why I came to New York. Many of the people who I turned to for understanding new worldviews, including Adrienne Maree Brown and Alexis Gumbs, are people who I went to college with and who I know and organized as a student with.

So I have a lot of gratitude for my specific experience in academia. I literally still have texts that I read from that I was assigned in college. I just don’t know if the work that we are doing specifically with Field Meridians is aligned with the larger goals of academic institutions of today.

I think that we can look at academic institutions in the ways that they disseminate knowledge as a specific model for knowledge sharing. For example, the syllabus, the course reader, I teach at Parsons. And so I have gratitude for the group of instructors and teachers who I get to teach and exchange ideas with. I love teaching there. I love having conversations with students. I just don’t know when it comes specifically to Field Meridians what type of synergy there would be, because it seems fundamentally at odds. What is considered valuable within an academic context, which is often capitalistic, is about production. Many of the professors’ tenure is predicated on production of knowledge in a formal system that then creates pathways for financial success for everybody.

ML:

I mean, I do think that the funding determines so much about the work that gets done and what the impacts can be. The wrong funding for the right kind of content can go down a very different path.

I am interested in what types of academic community alliances can start to emerge. How might the products, processes, timelines around this work also shift to engage other models of learning, which have siloed disciplines and privileged certain actors over others.

It’s a challenge because universities have a fantastic infrastructure and system of nurturing cultural capital. How do we leverage its tools and systems to also drive ways of understanding and valuing knowledge in the world?

LY:

I also think it’s important to recognize academia’s role in being a hedge against privatized knowledge, right? Look at AI–the majority of the work advancing AI happened in academic institutions and military funding. But it’s critical for knowledge to remain in the commons. And I’m not saying that academia should go away. I just think that the way it’s been working is not working right now.

ML:

Right, and one of the questions for me is– who participates in shaping other models of education that have remained stagnant for a long time.

LY:

I mean look at our election in the United States. It’s the result of our education system failing to help people be critical thinkers. As somebody with very young children, it has also really been a test as far as orienting myself towards certain educational opportunities for my children that align with my values around critical thinking and community.

We need to invest in actual futures, which is education for our children. And capitalism does not value that form of production, knowledge production, right? Because I mean, to quote Sylvia Federici, we need to invest in systems of cultural reproduction that are often stewarded by women. Those include art, education, health, etc.

ML:

As you mention, how do we evaluate that, see it and value it? And again, I think it’s beautiful that you go back to what most of your facilitators shared, which is acts of noticing. They make visible and all of the necessary mechanisms to circulate value back to these actors is key.

Part of me that wonders whether a lot of the work that we’re doing is in reaction to capitalist systems and the work of repair is still participating in these value frameworks, but accounting for the things that are complete blind spots in terms of returning value to our ecology, making visible, making sure people are attributed in terms of credit and economic potential and all of that stuff.

Or it’s a whole new system. We have to do away with this. But for me, it’s really a question of value. Who gets to create value? Who gets to say what is valuable? Who gets to say how that value increases and where it goes?

LY:

Part of being human is assigning value to the world around us. And I think the work of artists and designers who are world builders in their creative practices is about exploding or expanding the way that we assign value to the world around us. I remember being young and thinking, I don’t understand economics. It’s just numbers. It’s money. I don’t get it. Now I’m older being like, oh, economics is just about understanding systems of value and how that actually shapes the world around us.

ML:

On that note, I wonder if we could end on a vision of the future. I know you talked about the forest school and where you’re going with the winter programming. What does it look like to you in terms of imagining your thriving communities?

LY:

I would love to be able to go to a place within walking distance in my neighborhood to pick and harvest fresh food in the season. A place that I could walk around and learn about the season based on what was available. And to do so with my neighbors. Imagine a place of music, of art, of programming, of having a communal flame, (maybe a real fire pit), but also a social flame that we all keep together. I want it to be a place of rest and a place of healing, a place that we can just be who we are together. That is my vision. I want to hear about yours too.

ML:

I don’t know if I have a full vision yet, but I think it involves having an academic-community research institute somewhere, maybe in different places around the world. But essentially, it would be a place for a range of actors — a farmer, textile dyer, scientist, artist, architect, academic– to come together to experiment, do and reflect on different issues anchored around material research. A place where multi-directional and equitable knowledge exchange could happen. And the projects that come out of those frameworks would be locally-responsive but globally linked. I hope to grow old doing that kind of work somewhere in between community, academia and industry, but not necessarily fully in either.