Social Synergies investigates the social structures – both seen and unseen – that underpin food production and consumption.

We once gathered around fire to share food, two million years ago. It wasn’t until the 18th century that the restaurant emerged for leisure and sensory entertainment. As the world opens up post-Covid, what will be the lasting effect on the spaces, places, and moments in which we gather together for meals?

In the 18th century, dining with others expanded beyond family life, becoming a leisure activity that could also take place outside of the home. In lockdowns around the world, the spaces where interactions with food take place are experiencing a shift. Now the idea of consuming with others in close proximity is fundamentally challenged. However, the need to break bread together outside of the home remains—it is where bonds are solidified and formed, topics debated, philosophies discussed and conviviality enjoyed. After the release of various air flow diagrams that show the proliferation of Covid spreading in restaurant settings, it is clear our expectations must change, if only temporarily. In the time of our on-going pandemic, we need safe spaces to perform this ritual, and interior design solutions may not get us through the next few years. The new spaces where we experience food now present a social design challenge, an urban design challenge and a behavioral design challenge.

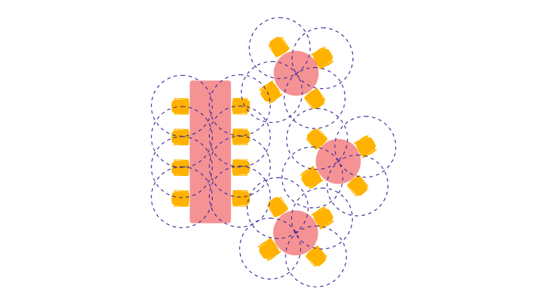

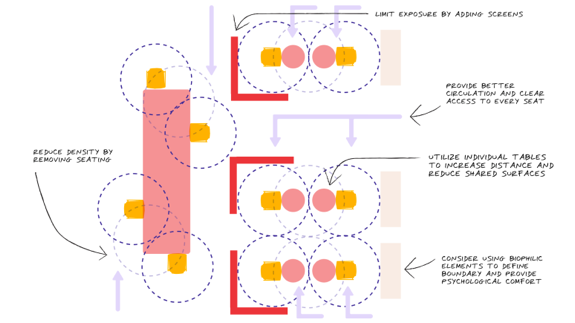

Thus far, no one has created a workable solution for the problems facing the hospitality industry. A recent study by Steelcase—one of the US’s largest office and retail furniture manufacturers—laid out shared space tenets for our future including ‘Density’, ‘Geometry’, and ‘Division’. Although far-fetched, Dan Roosegaarde’s UV space cleaner presents a possible way forward while Dining pods remain a farce and reduced capacity charts an unsustainable future for restaurants.

Current health advice to socialize outdoors could be an opportunity for us, rather than a disadvantage, and perhaps should be reframed as such. This gravitation could be the impetus to reconnect to the seasonality of food and eating, creating a trend for intentional and considered outdoor dining.Why not dine out seasonally, feeling and appreciating nature at each moment of the year? Just asJapan celebrates the start of the picnic season with the hanami cherry blossom festival, this synergy with the seasons should be reconsidered and valued. The challenges of indoor dining provoke new thinking in urban design, and how public spaces can be repurposed to serve communities coming together to share food. With the complexities of in-person gatherings, we should look to our imaginations in how we can enhance sharing food together with technology and virtual experiences.

This ‘outside’ approach offers an opportunity, not only for urban regeneration, but for community regeneration as well.

Can a shift to seasonally-conscious outdoor dining contribute to a reconnection with the rhythm of nature that is so desperately needed?

In the UK, Nomadic runs an outdoor dining experience in a woodland outside of London from April to December. Since 2018, their holistic approach to a ‘restaurant without walls’ has been exploring ideas of eating together in nature, “reconnecting people with the world around them”. Founder Noah Ellis emphasizes that food and nature are inextricably linked, and Nomadic’s events help reconnect participants to the bond that has been broken by our food supply chains. Throughout the year they trace the edible seasons: in spring guests are surrounded by bluebells and enjoy wild garlic and sorrel; summer brings its floral scents and berries; autumn is a fungi foraging feast; and in winter, the preserved produce harvested over the year is celebrated.

Could temporary pavilions enhance the “third space” we need in order to break bread together?

Designing performative experiences with food in both urban and rural landscapes—ones that facilitate relationships with nature, seasonality and community—is a field with both huge potential as well as many challenges. I spoke to Anna Maria Fink of Atelier Fischbasch, whose interdisciplinary design and research studio explores new methods and rituals to connect with space, place and landscape. Their project this past summer, ‘Im Fluss’ (In the River), created site-specific interventions in a river bed, including building an oven made from the river’s stones. This collective activity allowed the group to prepare and enjoy food together, and at the end of the project the oven naturally washed back into the river. Similarly, an open-source stove for construction in urban environments was created by Bits to Atoms for local Beirut residents. Their CAD file allowed for ‘Revolution Stoves’ to be easily cut and assembled, used by protesters to keep warm and make tea during the protests of 2019.

In our discussion, Anna also emphasized fire as a significant tool in creating a gathering place. In Vienna, public fire pits (made of large concrete plumbing pipes) in designated areas create a space where communities can cook and share together. These ‘unconfined spaces’—whether urban or rural—‘help facilitate spontaneous encounters and strong feelings of being in a place’. Though preparing and cooking together in public space can present logistical challenges, at least gathering, eating and sharing should be achievable. It is a problem so often dependent on municipalities, and their willingness to see the value in changing and adapting to new needs of the community. In German there is a phrase, Konsumfreier Raum, which means to consume space for free—something we may need more of to gather as communities to share food outside.

Recently I made a food pilgrimage for Uyghur cuisine in London, for both daily constitutional exercise and sustenance. Banned from indoor dining, a friend and I perched on a curb to share our meal in the dead of English winter. In the new normal, our space for eating was the urban environment, and there was hardly a functional seat or surface amongst the concrete. The experience made me consider the idea of pavilions, the celebratory yet practical nature of these structures for outdoor community gathering and exchange. If governments can’t commit to permanent fixtures for social exchange in our communities (and their constant paranoia of inhabitancy by the homeless), perhaps a temporary pavilion model could be applied to provide the space we need to break bread together. A notable example is the Serpentine Galleries’ program of dynamic pavilion commissions run for the past twenty years, creating a temporary shelter, space and place for meaningful exchange. More small-scale pavilions populating the city could alleviate the need for a commons in which to share food, and encourage moments of celebration and exchange within communities.

Dining outside in public space can be an inclusive experience, bearing in mind that not everyone can afford to dine indoors in the first place. For example Citycookbook.org has been promoting the use of public spaces in this way for years. Ray Oldenburg, who defined the essential ‘third space’ outside of home and work wrote, “The development of an informal public life depends on people finding and enjoying one another outside the cash nexus.” This ‘outside’ approach offers an opportunity, not only for urban regeneration, but for community regeneration as well. As Atelier Populaire wrote on their 1968 protest poster, ‘La Beauté est dans la rue” (The beauty is in the streets), eg beauty and truly meaningful culture and exchange comes from the action on the streets, rather than from inside bourgeois institutions or spaces. Herein lies the idea that outside of an exclusive indoor restaurant experience, is the potential for exchange between different members of communities in this ‘third space’ of the commons outdoors

Could multi-time zone virtual dinner parties be the new supper club?

Another approach is thinking outside of the box – outside of the takeaway box, into our imaginations and multi-sensory exploration. We have an opportunity to elevate these moments with meaningful or surreal experiences. Think of Salvador Dali’s surrealist gala dinners, the imaginary food in Disney’s Hook (1991), a Futurist dinner, an elaborate tea party from Alice in Wonderland. Or what if a virtual flying restaurant boat visited you for a chat and takeaway, like Corbin Dallas in The Fifth Element (1997)? Ironically in early 2020 before the pandemic shut down all restaurants, the mixed reality dinner party had already been tested at James Beard House by Aerobanquets. The eating experience incorporated virtual reality enhancements for the food consumed.

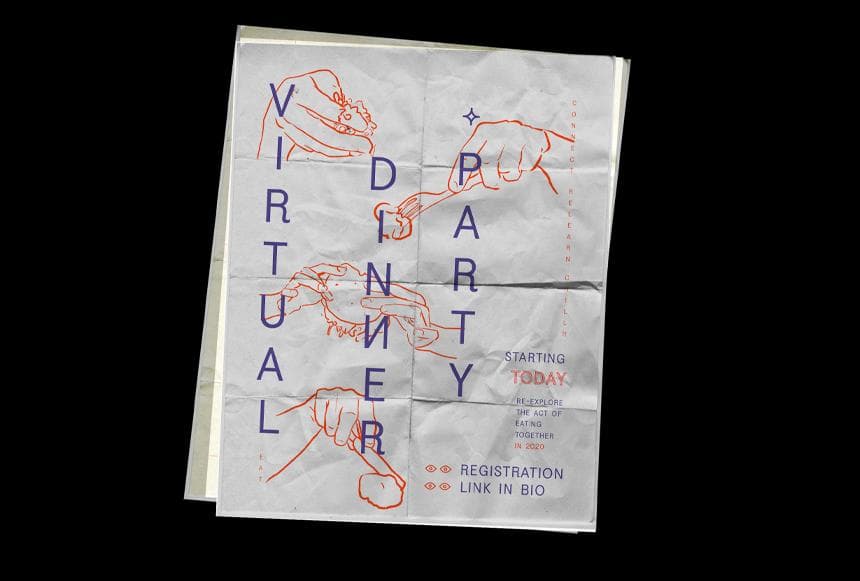

Headsets aside, a more attainable approach is available in virtual gatherings, such as the Virtual Dinner Parties as a place for exchange, initiated by Neeraja Dorde. These intimate gatherings connect people across the world who share food together, exchange stories, describe their cuisines, ingredients, rituals, context, and sometimes debate specialist topics. Neeraja said that of course you can’t always fly across the world to have dinner, but the exchange is easily facilitated online. It is possible that dining with people across the world could be more convivial than with your group of friends.

We’re going to need different speculative dimensions to share food, to get through the next decade of change in our eating spaces and habits post-COVID. And it’s not a question of looking inside, but out.