With another World Water Day come and gone, the majority of us will go back to enjoying the pleasure of running the tap as we brush our teeth, taking extra long showers each morning or grabbing a bottle of water at first thirst. Within the context of the United States, access to safe drinking water is always framed as a problem for distant others. But as recent events ranging from the ongoing Flint water crisis to the California droughts and the aftermath of Texas’ hurricane flooding have shown us, our own water security is really just a disaster season away. And as Dr. Upmanu Lall, director of Columbia Water Center, illuminated last night at the A/D/O Water Futures kickoff symposium, 2-4 million people in the United States don’t have access to drinking water. And if that’s not enough to make you sit up, consider that the water infrastructure in the United States is in a dire state of neglect, receiving an average “D” rating. To put that into perspective, in 1950 the average number of water mains breaking was one a year—that average is now one a day.

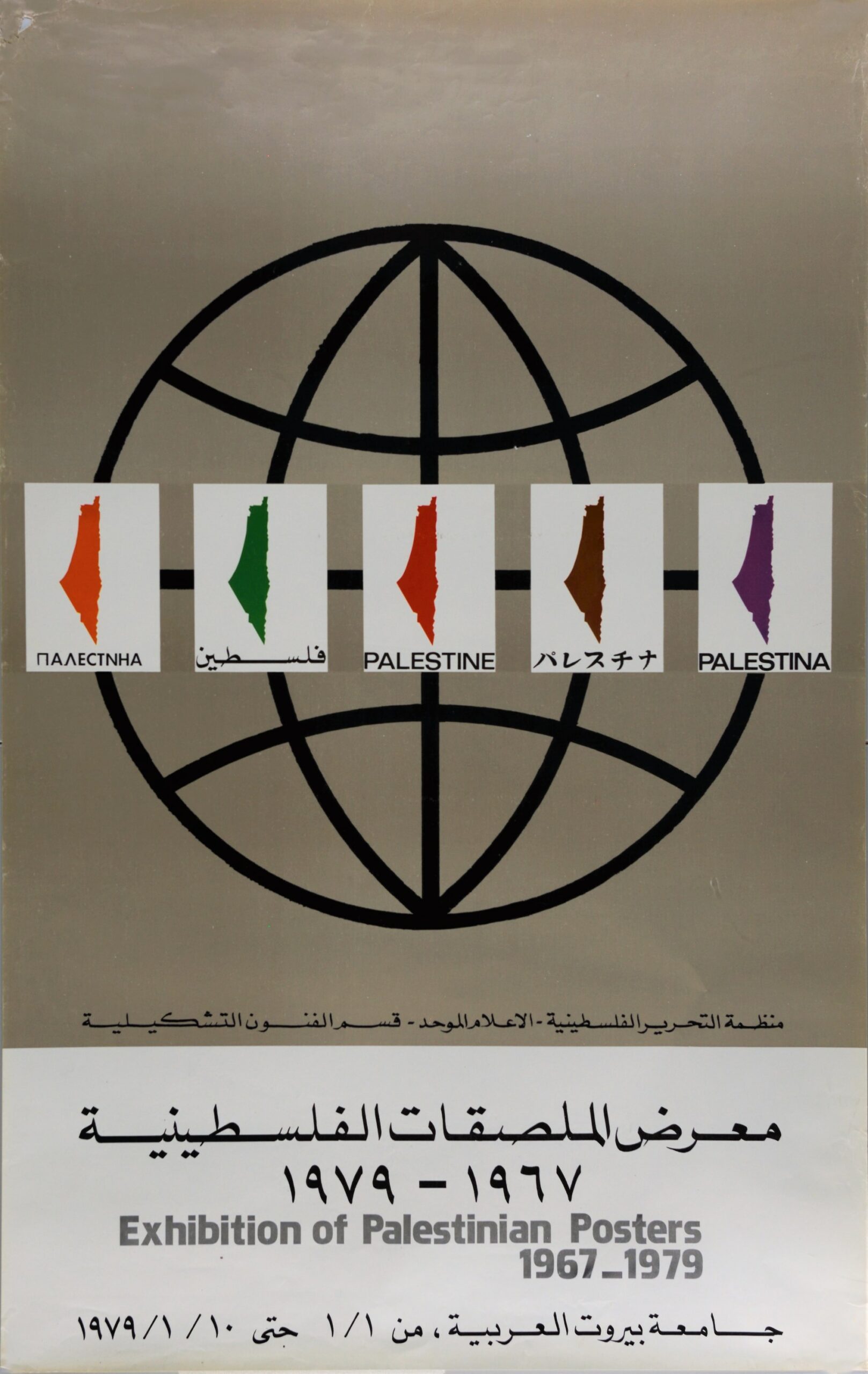

Water library collected from freshwater sources in and around Belgium from the Z33 exhibition, 1% Water and our Future

Water library collected from freshwater sources in and around Belgium from the Z33 exhibition, 1% Water and our Future

Today, A/D/O launches a year-long research program and design challenge on the future of fresh drinking water organized by the British design curator and educator Jane Withers. For over a decade, Withers has been exploring the challenges and richness of water culture. After leading her students in a project around bathing culture at Design Academy Eindhoven, Withers realized, “how little awareness there was around water,” she explained to MOLD. From this realization, Withers began exploring the myriad implications of water culture through projects like an exhibition co-curated with Ilse Crawford on the water crisis for Belgian design gallery Z33, infographics installed around Beijing’s hutongs asking diners, “How much water do you eat?,” and a Water Bar (and accompanying exhibition) to amplify Selfridges’ decision to stop selling single-use plastic water bottles in their stores. For A/D/O, Withers will be programming a series of talks and workshops around three themes (water harvesting, pollution & purification, refill culture) to engage multi-disciplinary teams in a design challenge to shape the future of drinking water in the urban environment.

Withers cites our “disconnect from the essential source of water,” as a primary reason for our continued disregard for water. “We just treat it as this kind of industrial liquid that comes out of the tap and we don’t really think too much for what isn’t there anymore,” she explains. “We’ve lost a lot of the closeness that allows us to use water both more responsibly but also more imaginatively and enjoyably.”

Researchers working in the Tule Valley in Mexico believe that cilantro could provide an inexpensive alternative to activated carbon filters. When dried, cilantro can be inserted into a tube for use as a filter, or placed into tea bags in a pitcher of water for a few minutes to absorb water impurities such as the presence of heavy metals. Other plants, like dandelions and parsley, may also provide similar capabilities.

Researchers working in the Tule Valley in Mexico believe that cilantro could provide an inexpensive alternative to activated carbon filters. When dried, cilantro can be inserted into a tube for use as a filter, or placed into tea bags in a pitcher of water for a few minutes to absorb water impurities such as the presence of heavy metals. Other plants, like dandelions and parsley, may also provide similar capabilities.

Sparking this sense of imagination and delight is at the heart of the Water Futures research program. The Water Futures design challenge not only comes with a $72,000 prize pool, but also a year of promotion and support from the A/D/O team as the challenge runs. We spoke to Withers ahead of the launch of the program and challenge on why its critical to engage designers in shaping the future of drinking water. Below are excerpts from our conversation:

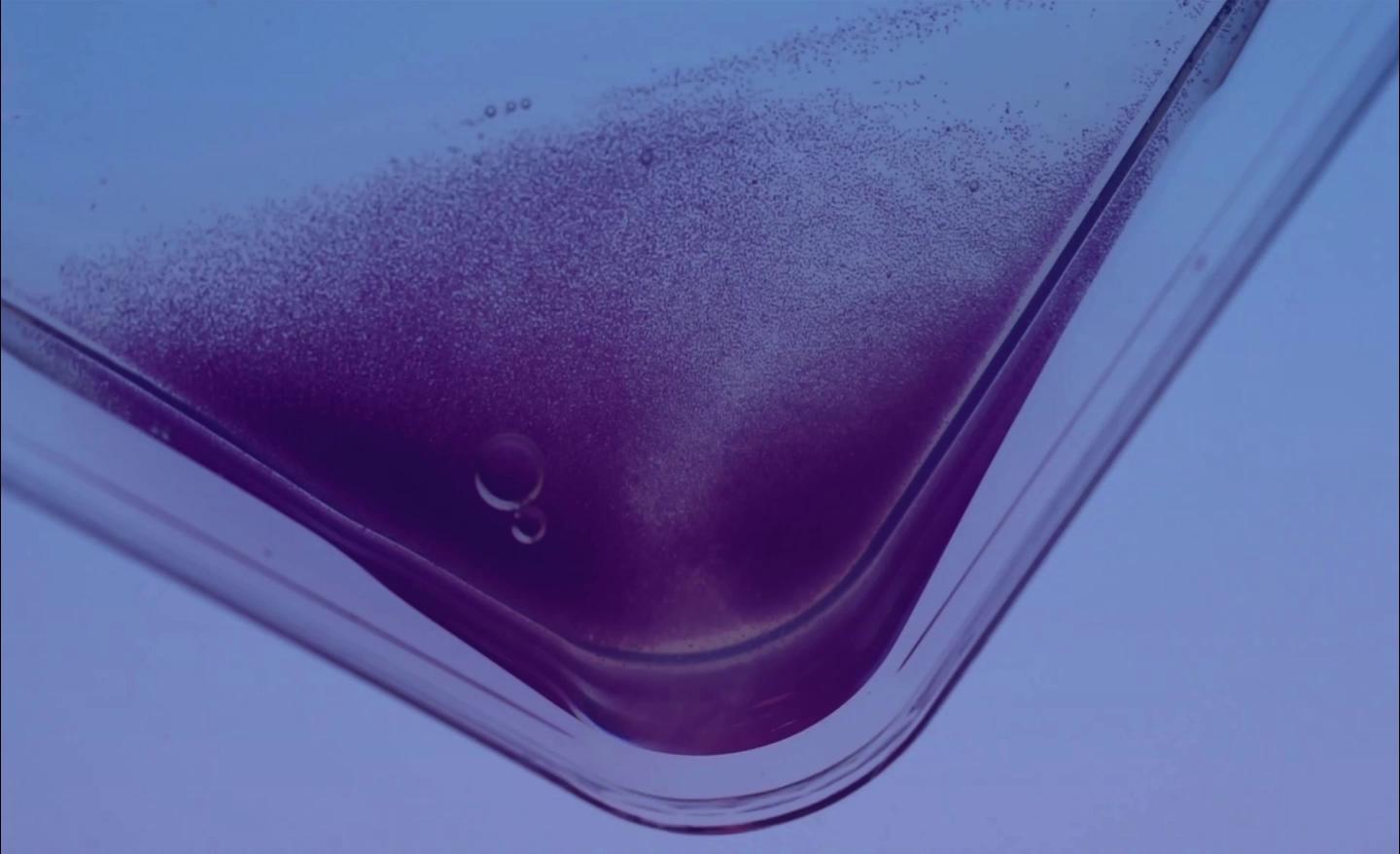

From Toilet to Tap

Jane Withers: Design can be very practical but it can also be the magic that helps engage people. I was talking to a leading water scientist a few days ago and we were discussing the A/D/O Water Futures symposium. He was very open to the engagement of designers because he said that waste water cleansing is going to be, at a local level, a very important issue. But he was saying that his engineers had some up with the phrase “from toilet to tap” which isn’t very appealing. If there are to be waste water cleansing systems on a local level what should those be? Can they be part of a pocket park in your neighborhood? What else can they do? Can they grow vegetables? You know, how do you make these into imaginative things?

1973 and Drinking Vessels

There is such a long history in every culture of storing, transporting and containing water. Since its been industrialized and comes out a tap, we’ve lost that kind of connection. Since 1973 and the arrival of the plastic bottle, it’s made our [visual] language even more monosyllabic. But there are, historically, so many great solutions. You used to have earthenware, terracotta, leather water skins—a whole rich design lineage around water and we’ve just reduced it to a plastic bottle. Because the culture was so rich and informed by so many centuries of use that often by going backwards, not in a retrospective way, the seeds [of culture] could be taken forward again.

Binchō-tan charcoal, produced in Japan for centuries, naturally absorbs toxins from tap water such as chlorine, lead, mercury, cadmium and copper. The charcoal has the added benefit of releasing useful minerals like calcium, potassium, magnesium and phosphates.

Binchō-tan charcoal, produced in Japan for centuries, naturally absorbs toxins from tap water such as chlorine, lead, mercury, cadmium and copper. The charcoal has the added benefit of releasing useful minerals like calcium, potassium, magnesium and phosphates.

Storytelling and Water as Living Element

The idea that in the 11th century Fatimid rulers would drink their water from rock crystal ewers. It’s quite extraordinary. Very often a museum label refers to the materials and craftsmanship but they miss out on the sort of stories, myths and associations that are perhaps a little more speculative, but quite informative too. But of course there’s a big culture around crystals and water today and energizing water. And then there is also the idea that through that, we should care about waters quality and think of it as a living element.

I think we sort of lost a bit of that. We were recently looking at a map of wells in central London, there were about 100, and imagine a time when people gathered by a well and knew which water was good for a laxative, which was for the liver… So there is that connection we’ve lost and I think it comes through in history. Very often, it’s about how you simply tell the stories about things.

On Refill Culture

One thing that is rather extraordinary is that your water [in New York City] is effectively Catskill’s spring water, but people aren’t aware of this. They prefer something that sat in plastic bottle for ages. So how can you influence mindsets and also make the behavior easier and intuitive? That’s one sort of cultural challenge for designers at work.

Pine trees contain sapwood (xylem), a porous tissue that serves as the tree’s filtration system that can also trap bacteria and micro particles. In 2014, an MIT research team found that freshly cut pine branches used as a filter to pour water through, remove 99% of E. coli bacteria.

Pine trees contain sapwood (xylem), a porous tissue that serves as the tree’s filtration system that can also trap bacteria and micro particles. In 2014, an MIT research team found that freshly cut pine branches used as a filter to pour water through, remove 99% of E. coli bacteria.

On the Plastic Water Bottle

Understanding the marketing power and the sort of functional genius of the plastic water bottle, the challenge will be to find something that can supersede that and make people want to change their behavior. Or inspire them to. These are big challenges which you don’t normally win by just saying “don’t use” and so on. You have to find an alternative that will be equally engaging.

Meet Me By the Fountain

In London at the moment there is a call for other systems, such as drinking fountains, for accessing water in the city. We’re beginning to see the arrival of lots of fountains, but they’re rather serviceable and functional rather than a beautiful addition to the city. Why can’t we have sort of have both? How else will you access water in the city? How can it be enjoyable? How do you make drinking fountains that people actually want to use rather than being afraid of hygiene issues? How do you make them something, perhaps, with an urban romance? You know, “Meet me by the fountain.”

The A/D/O Water Futures Design Challenge is open for submissions from now through June 21, 2018.