Pre-order your copy of SEEDS, MOLD Magazine Issue 05 here for a pre-order price of $18USD. Expected ship date is March 22.

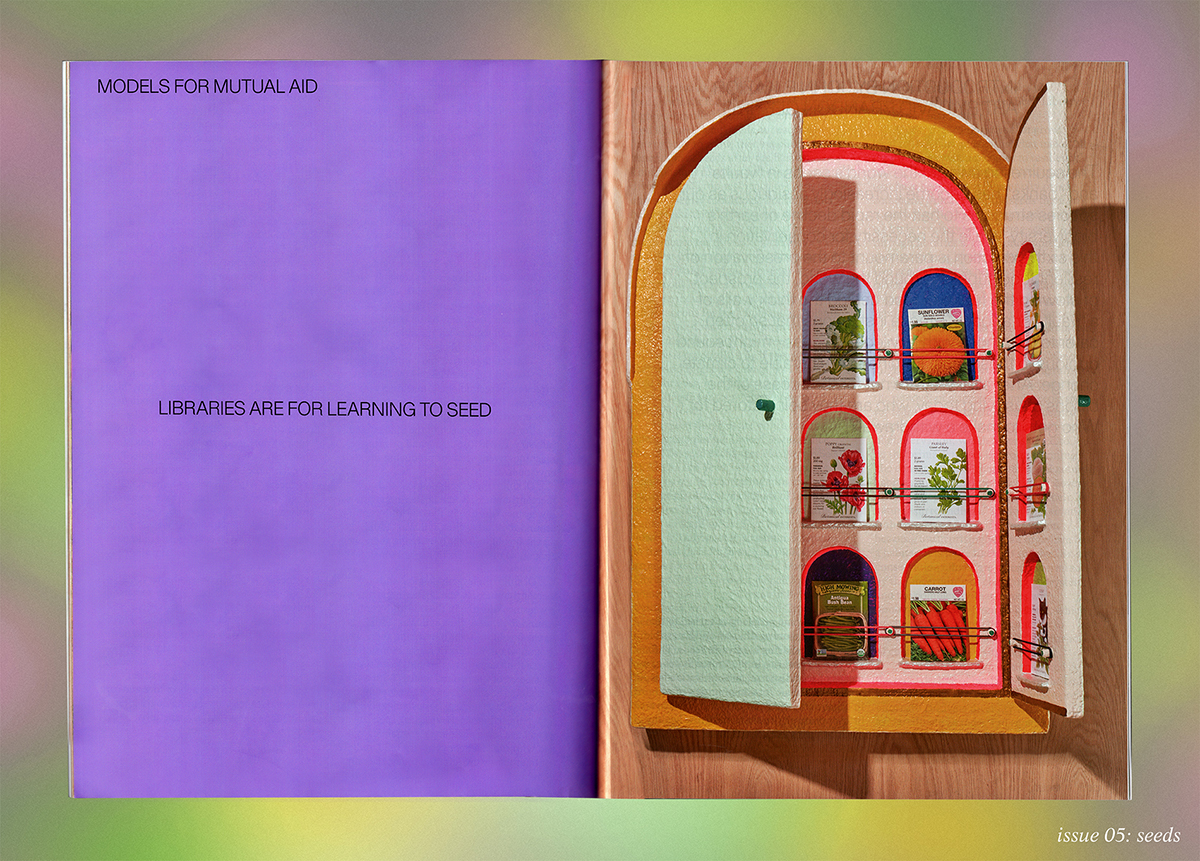

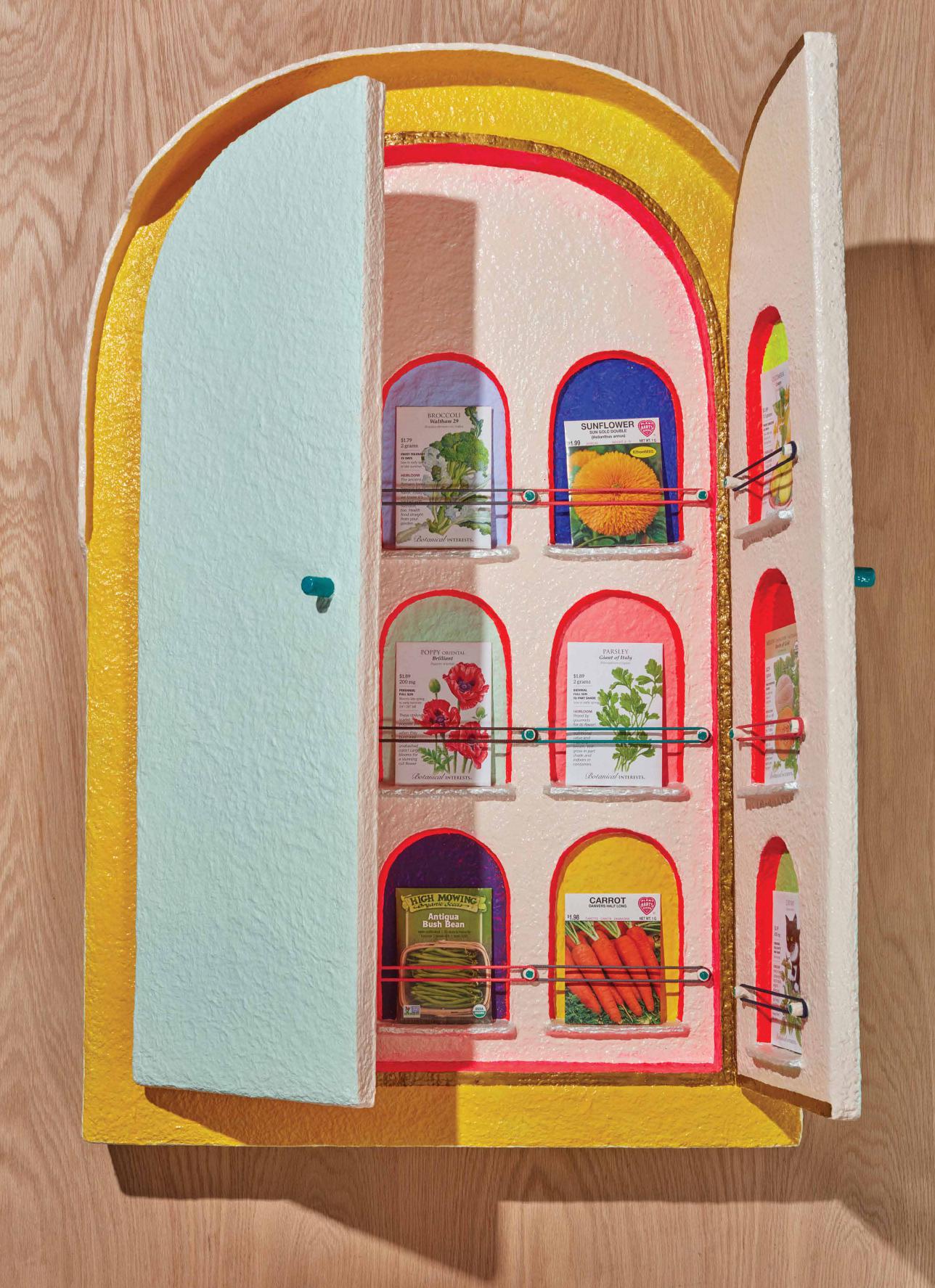

With the COVID-19 outbreak in New York City, we were alarmed by the seismic effect the quarantine had on our already food insecure city. The pandemic amplified systemic inequities in our current food supply chain and the failures of our globalized approach to feeding ourselves and our communities. Inspired by the rise of local mutual aid groups and the Little Free Library movement, MOLD commissioned seed libraries from our favorite New York designers and chefs with the hope that their approach might inspire others to freely share seeds and stories within their communities and beyond.

Artist statement by Angela Dimayuga.

Photography by David Brandon Geeting for MOLD Magazine.

While in Grand Cayman on an artist residency, I decided to start saving these seeds because, at the time, everyone was working on their own Victory Gardens and doing simple propagating—putting scallion ends in water, rooting mint. The farm that I got produce from was Clarence Farm. Clarence, the farmer and owner, is originally from Cayman Brac, but his partner, Christine, is Filipino and the farmers there are also Filipino. These seeds are from his produce.

I love Clarence Farm because Clarence made intentional choices around why and what he’s farming. He’s a black Caymanian man who, as a young adult, worked in finance on Wall Street. After that bout in New York, he decided to come back home to become a developer. While developing land in Grand Cayman he discovered a natural well on one of the pieces of land he bought.

With the discovery of this natural well, he decided to pivot towards farming. Growing up in Cayman Brac, his family and neighbors were all practical at-home farmers, tending to their plots of land. Most Caymanian families have a fruit tree, like a mango tree or breadfruit tree—a direct relationship with foods that are part of the culture.

I was always getting local eggs, so in this seed library there are hibiscus, soursop and moringa seeds, amongst others. Clarence first gave me these moringa seeds and shared how you could eat them as a kind of herbal medicine. Like many Caymanian men, he eats two seeds a day, basically for a healthy prostate. Eating the seed reminds me of the effect of eating a Sichuan peppercorn, where the flavor stays in your mouth for 15 minutes. The moringa seed has a really medicinal, bitter flavor. I like it. There’s a level of sweetness, and if you drink water afterwards, the flavor lingers in your mouth.

I first tasted moringa in a simple soup in the Philippines when I was sick. I had it in Batangas, where my dad is from, which has a more jungle-y terrain. It’s a health soup, similar to what you might find in Taiwan, Hong Kong and Korea, with a light chicken broth with medicinal herbs. We also braise green papaya, chayote or green mango until it’s really juicy. Then we add a lot of moringa and pepper leaves, which has such a beautiful flavor. But every time my mom made it for me in the United States, we used what we could find, so she would put spinach or Chinese water spinach in it instead. Getting to see an abundance of moringa in Batangas and understanding that it can kind of grow anywhere was really inspiring.

There are also a few commercial apple seeds. When I was in Grand Cayman, I was craving apples off season and buying mini bags of Honeycrisp apples. Through some research I learned that even if I planted those seeds, the apples that grow would be different—they wouldn’t produce “Honeycrisp” apples. The way we have commercial apples like Fuji, Pink Lady, or Honeycrisp is from grafting. Mangoes are also commercially grown through grafting—these are things that we aren’t taught. I also learned from the internet about how the seeds of the mango are actually inside the mango pit—you can shake some of the pits and hear the seed inside. I saw a video of someone opening the pit up, putting a seed on a wet paper towel and then watching it sprout.

On the farm they have over 40 different varieties of mango. It was beautiful to spend time there during the fruiting season and to taste so many different types of mangoes! In the United States, we only get access to the Mexican mango, but there, I got to taste, like, 12 varieties of mango on Clarence Farm. My favorite mangoes I tasted were these medium-sized ones called C11s. They were so flavorful and not fibrous, so you could actually eat the whole fruit.

Christine’s favorite mango is this tiny two-inch mango called a greenskin mango, and the skin is so thin that you can actually eat it. On the island they’re called “Blackies,” a name that is not politically correct, but they got that nickname because the color of the mango is green when ripe. These green mangoes are more challenging and the yield for the fruits is quite low. They’re not commercially viable. When I tasted it, I described the experience of eating balut, which tastes like the concentration of a dozen eggs in one egg. To me, the mango flavor, even though the fruit was very fibrous, was so beautiful and concentrated.

I have friends who have problems with eating mango because, for them, it’s too fibrous, and it might get stuck in your teeth. So one of my favorite things to do as a chef is to challenge people when they say things like, “Oh, I don’t like mango.” If they understood that there were hundreds of different varieties of mangoes, and so many different ways of preparing it, we’d know that, “Well, maybe there’s a mango for you.”