Pre-order your copy of SEEDS, MOLD Magazine Issue 05 here for a pre-order price of $18USD. Expected ship date is March 22.

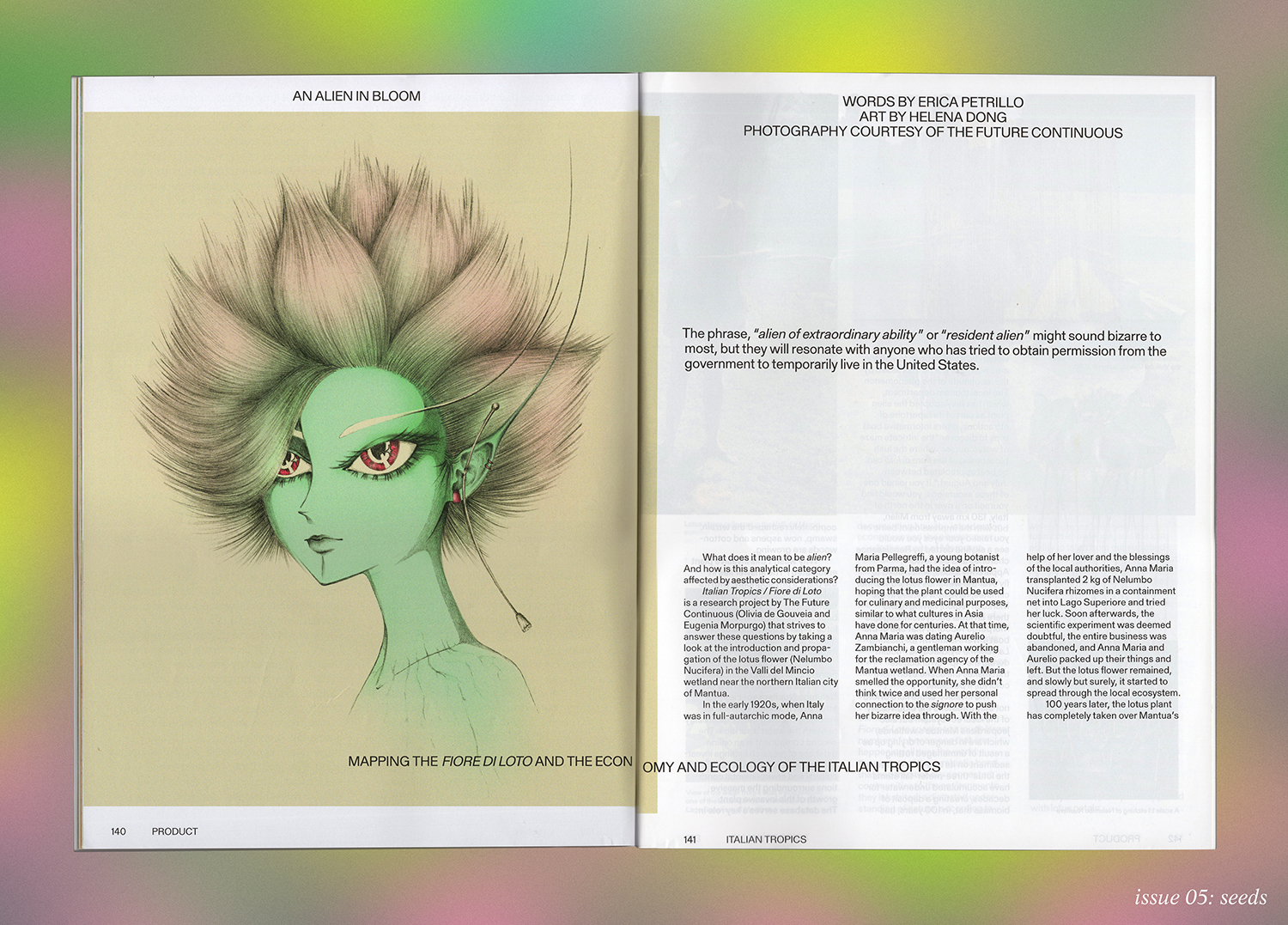

The phrase, “alien of extraordinary ability” or “resident alien” might sound bizarre to most, but they will resonate with anyone who has tried to obtain permission from the government to temporarily live in the United States.

What does it mean to be alien? And how is this analytical category affected by aesthetic considerations?

Italian Tropics / Fiore di Loto is a research project by The Future Continuous (Olivia de Gouveia and Eugenia Morpurgo) that strives to answer these questions by taking a look at the introduction and propagation of the lotus flower (Nelumbo Nucifera) in the Valli del Mincio wetland near the northern Italian city of Mantua.

In the early 1920s, when Italy was in full-autarchic mode, Anna Maria Pellegreffi, a young botanist from Parma, had the idea of introducing the lotus flower in Mantua, hoping that the plant could be used for culinary and medicinal purposes, similar to what cultures in Asia have done for centuries. At that time, Anna Maria was dating Aurelio Zambianchi, a gentleman working for the reclamation agency of the Mantua wetland. When Anna Maria smelled the opportunity, she didn’t think twice and used her personal connection to the signore to push her bizarre idea through. With the help of her lover and the blessings of the local authorities, Anna Maria transplanted 2 kg of Nelumbo Nucifera rhizomes in a containment net into Lago Superiore and tried her luck. Soon afterwards, the scientific experiment was deemed doubtful, the entire business was abandoned, and Anna Maria and Aurelio packed up their things and left. But the lotus flower remained, and slowly but surely, it started to spread through the local ecosystem.

100 years later, the lotus plant has completely taken over Mantua’s wetlands. If you happen to visit the area now, you will be impressed by the magnitude of the phenomenon. The local tourism department, which has fully adopted the alien plant as part of its repertoire of attractions, offers informative boat trips to discover “the intricate maze of watercourses, where the lush blossoming of the fiore di loto can be best appreciated between July and August.” If you joined one of these excursions, you would find yourself on a river in the north of Italy, 130 km away from Milan, but with the impression of being on the Mekong River. You would be surrounded by water lilies, but if you raised your eyes you would see a skyline dotted by Renaissance churches and bell towers. Apparently ibises, which used to fly over the wetlands toward warmer climates, have now settled in the Mantuan region, having found there an ideal ecosystem. Eugenia Morpurgo recounts that one of the boat drivers is known for blasting La bohème by Giacomo Puccini during the trip—an anecdote that makes the scene even more colorful, if possible.

The invasion of the fiore di loto not only threatens the biodiversity of the local ecosystem but also jeopardizes Mantua’s wetlands, which are in danger of drying up as a result of unmanaged rotting sediment on its bed—the detritus of the lotus’ three-meter-tall stems have accumulated underwater for decades, creating a deposit of biomass that, in 100 years, has completely reshaped the terrain, bringing it from 4m to 20cm of depth. Where once there was swamp, now aspens and cottonwoods are growing

Why wasn’t this invasive plant eradicated? The answer lies in the plant’s physiognomy, with its delicate blossoms and gorgeous fleshy petals that seem to wink back at you. In other words, the lotus remains there undisturbed thanks to (or masked behind?) its aesthetic appeal.

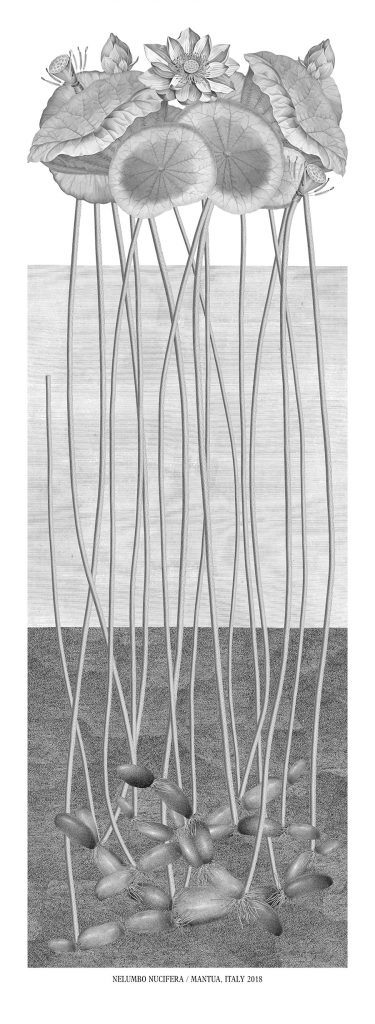

The project Italian Tropics / Fiore di Loto has two components. The first is a scale 1:1 etching of the Nelumbo Nucifera species—an attempt at making the invisible visible by showing the hidden reality beneath the water’s surface. The second component is an online database of research findings investigating the historical, economic, cultural and environmental conditions surrounding the massive growth of this invasive plant. The database serves a key role in documenting how the introduction of the plant has contributed to a rupture in the equilibrium between local economies and the environment.

In the words of Morpurgo, “The database was used to make the communities around the Valli del Mincio aware of the story of the lotus in that region and of the entangled relationship between the general local management of farmed land and the impact that the lotus is having on the Valli ecosystem. Before proposing any action, it was fundamental for us to engage with an informed local community.”

By diving into the folds of a situation that is specific to a particular geographical and historical context, in reality Italian Tropics / Fiore di Loto speaks to a much larger number of phenomena that are happening all over the world: the rupture of the symbiotic bond that had traditionally connected communities to the environments they inhabited; a distorted understanding of nature, according to which humans are somehow removed from it; a strong disconnection from embodied, unmediated forms of knowledge and the lost ability to learn from our surroundings. And also, crucially, the project reveals the nefarious effects created by the dominance of the tourist economy, the short-sighted management of natural resources, protected areas and farmlands alike, and the impact that climate change has on our lives. Finally, the “lotus story,” recounting the vicissitudes of a flower that arrived in the Mincio area in the form of 2kg of rhizomes, which now occupies 80 hectares of land, is emblematic of the power of “aggressive beauty” in shaping our understanding of alienness. Italian Tropics / Fiore di Loto reminds us that what divides the two equations “alien = invasive species to be weeded out” and “alien = welcome addition to the local ecosystem” is a very thin line, one possibly paved with lotus petals.