From MOLD Magazine: Issue 02, A Seat at the Table. Order your limited edition issue of MOLD Magazine here.

If we’re being totally honest, our idea to create a timeline of iconic dining objects for this issue didn’t initially spring from any grand pedagogic ambition to illustrate the history of design through the lens of one of humankind’s most universal rituals. It sprung, rather, from a chance late night encounter with a particularly nostalgic bit of pop culture: the Beetlejuice dinner party scene. Strange as it may seem, it was rediscovering that scene — with its amazing granite-slab table, ROLU-esque animalpelt dining chairs, and Memphis-style shrimp bowls — that eventually made us think about what other great dining-related moments and designs have made their mark on history, from Meret Oppenheim’s conceptual fur teacup to one of the most recognizable (if useless) lemon squeezers of all time. This list was driven by the idea that the most iconic objects aren’t necessarily the most functional or intellectual ones — they’re the ones that are ultimately the most memorable.

— SIGHT UNSEEN

Text by Tiffany Lambert.

C. 1878

TOAST RACK – CHRISTOPHER DRESSER

Designed a full four decades before the influential Modernist program at the Bauhaus, the British designer Christopher Dresser created pared down, sparse, geometric objects that were quite radical for their time. But unlike many of his contemporaries who embraced craftsmanship and abhorred industry, Dresser’s silver-plated metalwork are among the earliest celebrations of an industrial aesthetic meant for manufacture, as evidenced by the simple elements with exposed rivets. After a trip to Japan in 1877, Dresser denounced decoration in favor of more sober forms.

C. 1910

WIENER WERKSTÄTTE TEA SERVICE —JOSEF HOFFMANN

A collaborative association between the public, designers and craftsmen, the Wiener Werkstätte celebrated craft through industrial production. Founded by Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser, and Fritz Wärndorfer in 1903 in Vienna, the Wiener Werkstätte placed emphasis on quality, including lavish materials such as hand-formed silver, semiprecious stones and ebony. This tea set illustrates the synthesis of all aspects of a design, from the decorative to the structural components, and symbolizes how the Viennese avantgarde sought out a utopic vision for a total work of art, or gesamtkunstwerk, in their domestic objects.

C. 1926

FRANKFURT KITCHEN — MARGARETE “GRETE” SCHÜTTE-LIHOTZKY

In the first quarter of the 20th century, there were turbulent debates about women and their role in society. The design of kitchens became a place for this debate to play out in the pursuit of greater efficiencies and domestic hygiene. Grete Schütte-Lihotzky’s Frankfurt Kitchen was a low-cost solution for municipal housing built in the late 1920s in Frankfurt, Germany. With approximately 10,000 units produced, Kitchen was an early step toward creating a more egalitarian world, and an early work by a female architect.

C. 1936

OBJECT (LE DÉJEUNER EN FOURRURE)— MERET OPPENHEIM

Inspired by a conversation while dining with Pablo Picasso and Dora Maar at a Parisian cafe in 1936, Swiss artist Meret Oppenheim created her famous Surrealist piece, known in English as Breakfast in Fur, when she was just 23 years old. Her fur-lined teacup, saucer and spoon instantly became an icon— the Museum of Modern Art in New York quickly acquired it — transforming a stereotypically feminine object into sexually charged tableware. Oppenheim went on to be productive in jewelry, furniture, costumes and poetry in an oeuvre that eschewed the Modernist need for unity, instead embracing a constantly evolving methodology in her artistic practice.

C. 1960

SERVING CART FROM THE FOUR SEASONS — GARTH AND ADA LOUISE HUXTABLE

Generations of powerful clientele wined and dined at the Four Seasons restaurant, which opened in 1959 through a design partnership between architects Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson. The storied modernist vessel was known to regulars for its rosewood bar designed by Johnson, large-scale brass rod sculpture by the artist Richard Lippold, banquets and furniture by Knoll, and bar cart and glasses designed by Garth and Ada Louise Huxtable, the first full-time architecture critic of The New York Times.

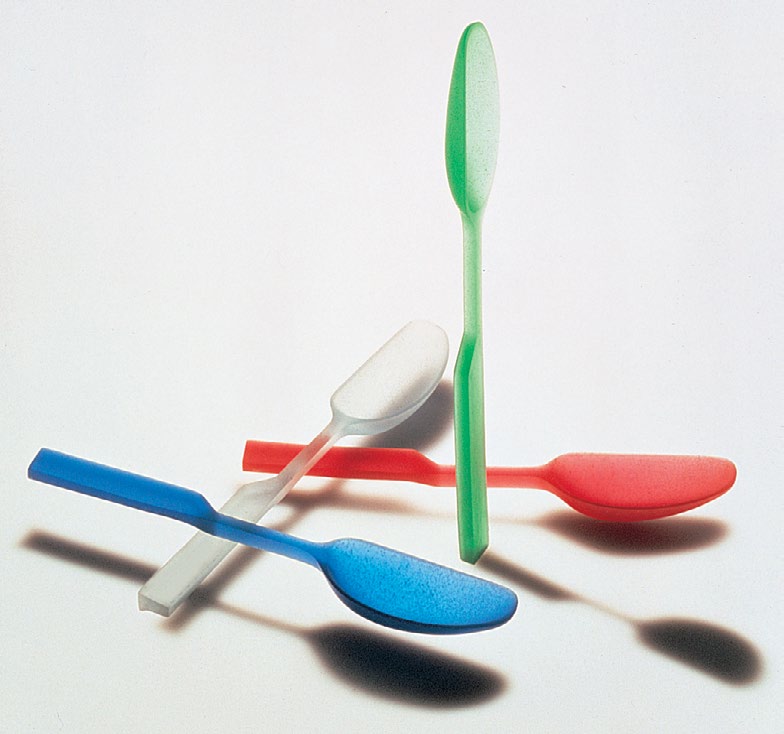

C. 1962

SLEEK SPOON FOR JARS — ACHILLE AND PIER GIACOMO CASTIGLIONI

Originally created for Kraft Foods in 1962, Italian design titans Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni’s Sleek spoon for jars embodies their whimsical, playful approach to functional, everyday objects. Sold by Alessi since 1996, the design was developed by casting the inside of a standard mayonnaise jar to determine the exact curvature for the spoon to remove every last amount of a condiment.

C. 1968

SPOON STRAW — ARTHUR A. AYKANIAN

Part drinking straw, part spoon, Arthur A. Aykanian’s striped spoon straw is an innovative rethinking of two useful objects and an exploration in plastic. Developments of injected molded polymers in the 1960s paved the way for a less rigid, more reliable material. Since then, designers have experimented with plastics to transform the built world. The disposable spoon straw is generally associated with Slurpees.

C. 1958

PEG BOARD FROM JULIA CHILD’S KITCHEN

By introducing French cuisine to an American audience, the chef and television personality Julia Child was the leader in a gourmet revolution. Not only did Child create the bible of French cookbooks, she brought stylish organization in the form of her now iconic pegboard: painted blue and adorned with 30 French copper pots, with a mapping system for every item. The entire kitchen of the maven of American cookery’s Cambridge, Massachusetts home was donated to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

C. 1973

CIBI WHISKEY GLASSES – CINI BOERI

For many years, Cini Boeri has been a leading figure of Italian design, but she also contributed to the seminal Postmodern sci-fi film Blade Runner, where her CiBi whiskey glasses were featured prominently. Handmade and mouth-blown by Arnolfo Di Cambio in Italy since 1973, the glass was selected by director Ridley Scott and reappears in the 2017 adaptation of the film, Blade Runner 2049.

C. 1968

9093 TEA KETTLE FOR ALESSI — MICHAEL GRAVES

After finishing school, Michael Graves worked in George Nelson’s office from 1959-60 where he learned about the work of Alexander Girard. Girard, best known for his colorful textile designs for Knoll, was likely to be an early inspiration for Graves’ own interest in color. In his Whistling Bird tea kettle for Alessi, Graves uses red to signify the heat of the steam whistle while the blue handle relays that it is cool to the touch. Historically Alessi’s best selling product of all time, the kettle symbolizes the Postmodern notion that, beyond functionalism and formal considerations, objects can be poetic.

C. 1988

TABLE FROM BEETLEJUICE

Cinema and design have long held a dynamic relationship. Beetlejuice, a haunted house comedy from 1988, had an aesthetic all of its own that might be described as matter-of-fact Surrealism. A pair of ghosts—a recently deceased young couple— haunt their former home in an attempt to scare away the new tenants. The characters of the living inhabitants mesh with the set designs. Particularly memorable is the granite slab dining table, which evokes a deadpan sense of otherworldly derangement.

C. 1990

SALAD SUNRISE OIL AND VINEGAR BOTTLE FOR DROOG DESIGN – ARNOUT VISSER

Conceptual Dutch design of the 1990s and early 2000s used irony as a device, often with a sparing use of resources, recycled materials and a deliberate, makeshift lack of style. Taking advantage of the natural properties of the oil and vinegar used to make a salad dressing, Arnout Visser worked in this conceptual style letting the liquids drive the overall aesthetic and form—oil naturally rises to the top, creating a distinct visual separation between the two.

C. 1990

JUICY SALIF LEMON SQUEEZER FOR ALESSI — PHILIPPE STARCK

The epitome of the art object, French designer Philippe Starck’s work of the 1990s emphasizes form over function and a predilection for a biomorphic aesthetic. Starck’s Juicy Salif highlights narrative more than considerations of use: it is the object’s sculptural quality that stands out.

C. 2016

PORCELAIN EGG CUP FOR THE THING QUARTERLY — RICKY SWALLOW

Egg cups as a typology have existed since before Pompeii was buried under the ash of Mount Vesuvius. Since then, they have been made in a variety of materials—silver, ceramic, wood, glass, melamine— and styles. Martha Stewart has a vast collection of them (collecting egg cups is termed pocillovy) and in 2016, the Australian sculptor Ricky Swallow created one for The Thing Quarterly. Based on a peg designed by the Shakers, Swallow used ordinary materials such as cardboard and glue to interpret the domestic form.