From MOLD Magazine: Issue 02, A Seat at the Table. Order your limited edition issue of MOLD Magazine here.

Often the seed of a great idea begins with a simple list. In this case, it was a grocery list. In 2012, Martin Kullik decided to become vegan. After visiting a number of organic grocery stores in Amsterdam, where he and his partner Jouw Wijnsma are based, Kullik noticed that most of the legumes sold were sourced from China. This troubled Kullik. He knew that The Netherlands produces a variety of beans. In fact, some significant varieties produced in Friesland, where Jouw’s family resides, are included in the Slow Food Ark of Taste.

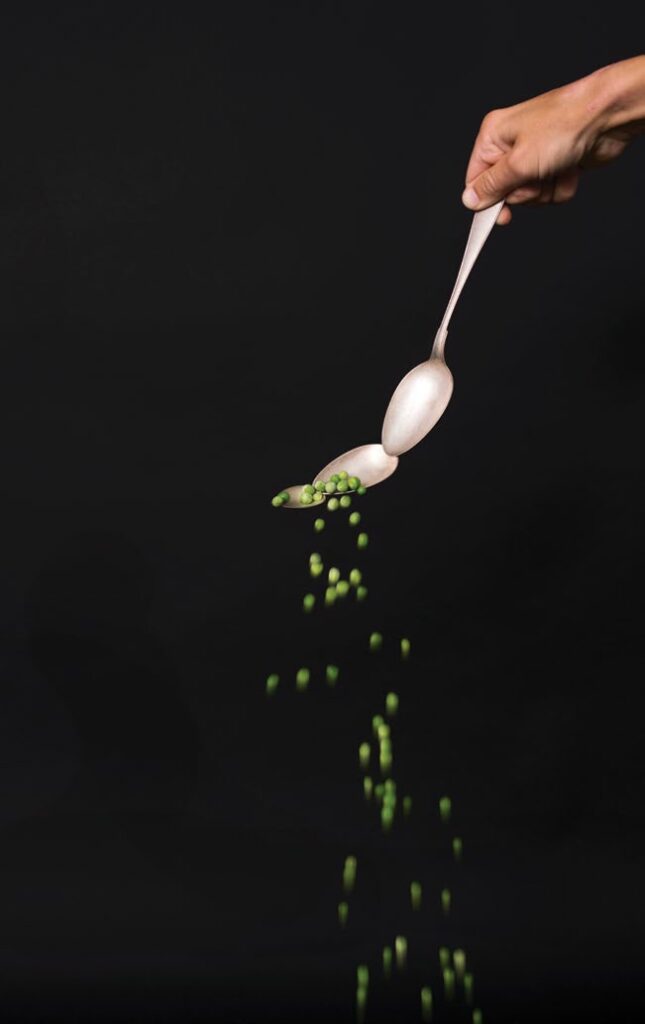

Photos by Annegien Van Doorn.

So Kullik and Wijnsma, who had also been curating experiential projects combining fashion and jewelry design with performance art under the name Steinbeisser, began to compile a list of local food producers. The logical next step was an event that combined their professional expertise with their personal passion. In 2012, Steinbeisser invited a local chef to develop a vegan dinner using only biodynamic ingredients sourced from local producers. They also decided to continue their curatorial work by commissioning the jewelry designer Maki Okamoto to design innovative utensils and tableware specifically for the occasion. From a small dinner with 27 guests priced at 27 Euros for a five-course meal, Experimental Gastronomy has become a celebrated international event with pop-ups in Basel, San Francisco and Berlin. On the heels of celebrating five years of Experimental Gastronomy, Kullik reflects on fusing function and aesthetics, the importance of designing with found materials, and how utensils can cultivate mindful dining rituals. — LinYee Yuan

***

Martin Kullik: We hosted our first dinner in July 2012, and it was quite a small—we had 27 guests. We created the project to invite chefs to explore vegan cuisine using 100% locally-sourced, biodynamic ingredients so, in Amsterdam, they can’t use olive oil, vanilla, avocado or mango—focusing only on what’s here in The Netherlands and seeing what one can do with that. Because our background is in curating, we wanted to invite artists, of course, to participate. So we invited the jewelry artist Maki Okamoto to create the cutlery for the event—she’s the one that made those connected fork-spoons.

When we first started working in fashion, jewelry and applied arts as Steinbeisser, we noticed that function and aesthetics were drifting apart. Functional objects would not be very aesthetic, or something aesthetic would not be very functional. And that really got on our nerves. As we defined the concept for Experimental Gastronomy, we wanted to create pieces that are aesthetic, but they have to be functional. That means that although the artists reinterpret the cutlery and dishware, the objects have to be able to serve food. Some objects manage to fuse both—to be aesthetic and functional at the same time—while other objects are more experimental.

When commissioning tableware, our first design parameter is the piece must be made from natural materials. Then, we ask the artists to recycle, upcycle and reuse materials as much as possible. If 100% of the pieces created are made of recycled, reused or found materials, that would be perfect. We focus on reusing materials because there’s already a lot of garbage in the world. By taking objects that have fallen into disuse, we can reshape it and give it a new life—a new purpose.

In our experience, we like working with jewelry designers and artists. A lot of designers know how to project ideas, sometimes using software or sketching, but they aren’t making the objects themselves. That’s not how we want to work. We aren’t making mass products—we like the handmade and the feeling of the artist’s hand. One can shape pieces like Maki Okamoto, where she cut cutlery pieces apart and then fused them together. There’s also Nils Hint who reused old Soviet tools. As a blacksmith, he reshaped them and connected tools with cutlery or melted cutlery out of tools. Stuart Cairns used a lot of found materials because every morning he walks along the beach and finds things like driftwood and plastic. He takes those pieces and asks: What kind of element should I connect to these found materials so that they can become a spoon or a vessel that can be used?

Most of our dinner guests are really excited to have a go at the pieces. They take their time. They explore how one might use the pieces, so the whole process of eating becomes much slower. While they’re eating, they look at the pieces, and they’ll put the piece down in between bites. Some people might say, “Oh, no I demand a standard spoon.” But then I sit down with the guests and I say, “You’ve come to this dinner, and it’s a special experience. It’s only one night, and you’ve come here on purpose. After all, it’s called Experimental Gastronomy.” We haven’t had a guest go for the standard spoon yet. People struggle with it, they might get angry or frustrated with the pieces, but in the end, they still try to have a go at it.

If guests understand that these pieces were created specifically for the evening and for their use, they feel really appreciated. This same feeling can be achieved if you were to pay the same attention that goes into preparing a dish into creating the cutlery and the dishware that you use to serve and eat food. The cutlery and the utensils we use every day can inspire people to be more conscious about what we eat. Our daily habits feed us and we should pay more attention. With the right tools, routine is much more precious.