From MOLD Magazine: Issue 03, Waste. Order your limited edition issue here.

My phone dings with the arrival of a message. It’s my fridge. The tomatoes nestled within it are expiring. Three more days, it tells me, and they’ll be mush. They would, however, be perfect in a ragu and I’ve most of the other ingredients needed: the carrot, the celery, the onions, although not the beef, which it offers with one button-click to have delivered to my home tonight, or tomorrow, or the day after. It goes on: it suggests reordering tomatoes and displays via my phone the optimum place to store them, but fewer this time, given that I’ve left my last few purchases get to this state and had to transfer one recent moldy bunch to the composter.

Text by Johnny Drain. Photography by Corey Olsen.

Since the 1950’s, fridges have helped households keep produce fresher and more nutritious for longer and extended the life of leftovers. However, the fridge has also remained somewhat one-size-fits-all: one cavity, one temperature, one humidity. In essence, a big, fairly un-nuanced, cool-box. For instance, to keep vegetables tip-top requires a certain amount of moisture, but many conventional fridges are on the dry side, especially if they share an air supply with a freezer compartment. In contrast, meats might benefit from that slightly less humid environment. Eggs don’t mind humidity, but they do absorb odors—good and bad—from produce around them. The challenge, then, for designers and engineers is to build fridges that provide flexibility and the best conditions for preserving a range of foods.

For fruit and vegetables—50% of which grown globally gets lost or wasted—“spoiling” is merely part of a timeline that also includes ripening, the passage along which, and that of their neighbors, is hastened by the ethylene gas that many of them give off. A number of companies like OXO and Whirlpool have products equipped with replaceable sachets or panel filters that claim to absorb ethylene while premium refrigerator models from brands like Bosch, GE and Sub-Zero offer built-in technologies that absorb, break down or inhibit ethylene. Sub-Zero’s airconditioning-like unit removes ethylene via a set of chemical reactions, along with various microbes. As the company’s VP of design engineering Paul Sikir clarifies, “we developed it with a local university who had worked with NASA to demonstrate how they could preserve food longer on space stations. These same basic principles were then used by food suppliers to avoid spoilage in warehouses. We just scaled it down to a very compact system that fits in a fridge.” Perhaps the ethylene extracted from one fridge compartment might one day be pumped into another where fruit could be intentionally ripened quicker; no more waiting around for hard pears and plums to sweeten. And the sensors that detect tell-tale emissions of certain gases to alert us to food turning bad might also let us know the optimum time to eat our avocados based on our personalized preferences for firmness.

Besides whizz-bang sensors, filters and internet-of-things integration, much cutting-edge research goes into making fridges and freezers more energy efficient. While less exciting, it will be these developments that start to benefit those most in need of food security in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa and the world’s expanding middle classes. One beautifully simple, inexpensive refrigeration solution that is already helping rural communities is the clay pot cooler. Consisting of two clay pots separated by a cavity packed with wet sand, it uses evaporative cooling to keep food cool without electricity. It has been shown to reduce diseases due to spoiled food, create work for local pottery-makers, and increase school attendance of young produce sellers by extending the window over which their products can be sold.

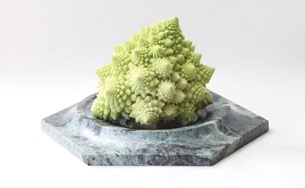

Such evaporative cooling systems have also appeared in designs by those questioning whether our reliance on electric refrigeration is entirely a force for good: by allowing us to delegate food preservation— increasingly out of sight—do fridges make us lazy and more wasteful? In 2011, industrial designer Péter Gál collaborated with Philips on a conceptual “domestic ecosystem”, The Microbial Home, that featured a vegetable-storing evaporative cooler built into the middle of a dining table, bringing fresh produce center-stage rather than buried at the bottom of a fridge. Gál’s work also probed how putting home food waste to good use can be made more accessible (although the prime focus should always be on preventing food waste) with a kitchen island that contained a bio-digester for turning organic waste into methane gas for powering other home appliances like the stove top. Similarly, Jihyun David’s Saving Food From The Fridge features five kitchen tools for storing foods outside the fridge in a bid to preserve them better and celebrate their form and beauty. In one, root vegetables are kept fresh by being stood vertically in dampened sand and in another, Symbiosis of Potato+Apple,the ethylene given off by apples actually suppresses sprout growth in the spuds that sit beneath them in a darkened maplewood tray. This modular approach of tools with more specific tasks is being echoed by conventional fridge developers too.

Moving away from bulky, white or chrome carbuncles in the corner of kitchens, there is a trend towards smaller, but multiple, below-the-counter refrigerated pull-out drawers. These offer a more tuneable system of holding temperatures and humidities for produce with different requirements and make it less easy to neglect foodstuffs in those hard-to-reach fridge corners. Although there will always be people who want centrepiece appliances, for the most part people want them to be less visible: in many ways the fridge as we know it is disappearing.

Indeed, as a recent inhabitant of a houseboat on London’s canalways when my fridge broke—I shorted it, playing DIY—I chose not to replace it. A 30-liter Thermobox, instead, allowed me to keep things entirely chilled during the winter and early spring months (one benefit of the British weather) and modified my purchasing and eating habits in not entirely unpredictable ways. Six months into the experiment, I buy more fresh vegetables more often, more cured and fermented products (yogurt over milk, charcuterie over fresh meat), cook more precise portions to ensure fewer leftovers, drink more red wine over white, and, regrettably, eat less ice cream. Already fairly hot on not wasting food, I squander even less now and am more mindful of what I buy and how it will be used. (Boat life is conducive to this anyway: what is brought aboard must be taken ashore, in some form, at some point!) As the weather has warmed up, the cool box isn’t quite as effective: milk doesn’t keep much more than two days. But if I do buy a fridge-freezer, I’ll get a small one, largely for drinks, ice, and, obviously, ice cream.

Whatever form they do take, and whether they have the ability to message us and organize our shopping, the challenge remains for designers and engineers is to build food storage solutions that provide flexibility, in keeping with changing lifestyles, and to help us develop habits that ensure we eat more and waste less of the food we bring into our homes.