Pre-order your copy of SEEDS, MOLD Magazine Issue 05 here for a pre-order price of $18USD. Expected ship date is March 22.

Can design empower community? The founders of the North Philly Peace Park (NPPP) believe the answer to that question could be a resounding “yes” for the legacy of the community in Sharswood. A historically black neighborhood in North Philadelphia, Sharswood has been ravaged by urban renewal projects over the years, along with the crime and poverty that has beset it since. Amidst rapid gentrification, the NPPP has a clear mission: to cultivate the potential in abandoned land and food apartheids to create productive sources of food supply and community building. To reach its goals, NPPP is establishing a new paradigm for ethical redevelopment—starting with the people and building up.

The North Philly Peace Park began in 2012 when founder Tommy Joshua Caison and his neighbors turned a couple of vacant lots into a community garden. After losing that land to a Philadelphia Housing Authority redevelopment plan, NPPP moved to its current location along Jefferson Street in 2016. Located in one of Philadelphia’s food apartheids, the garden has helped tackle issues of food insecurity and health disparities within the neighborhood. In North Philadelphia more broadly, about 30% of residents face food insecurity, and in some parts of Sharswood, residents have to walk upwards of 20 minutes to reach the nearest grocery store.1 Such a lack of quality food—particularly fresh produce—can lead to health conditions like heart disease and diabetes, which studies have shown tend to disproportionately affect black communities. Indeed, health issues are a major barrier for people living in the neighborhood, with about 35% of residents citing health issues as part of their difficulty in finding and retaining employment.2 Through its fence-free eco-campus, the NPPP has the potential to transform the physical space in Sharswood while also radically shifting the way local residents think about and approach their relationship to food.

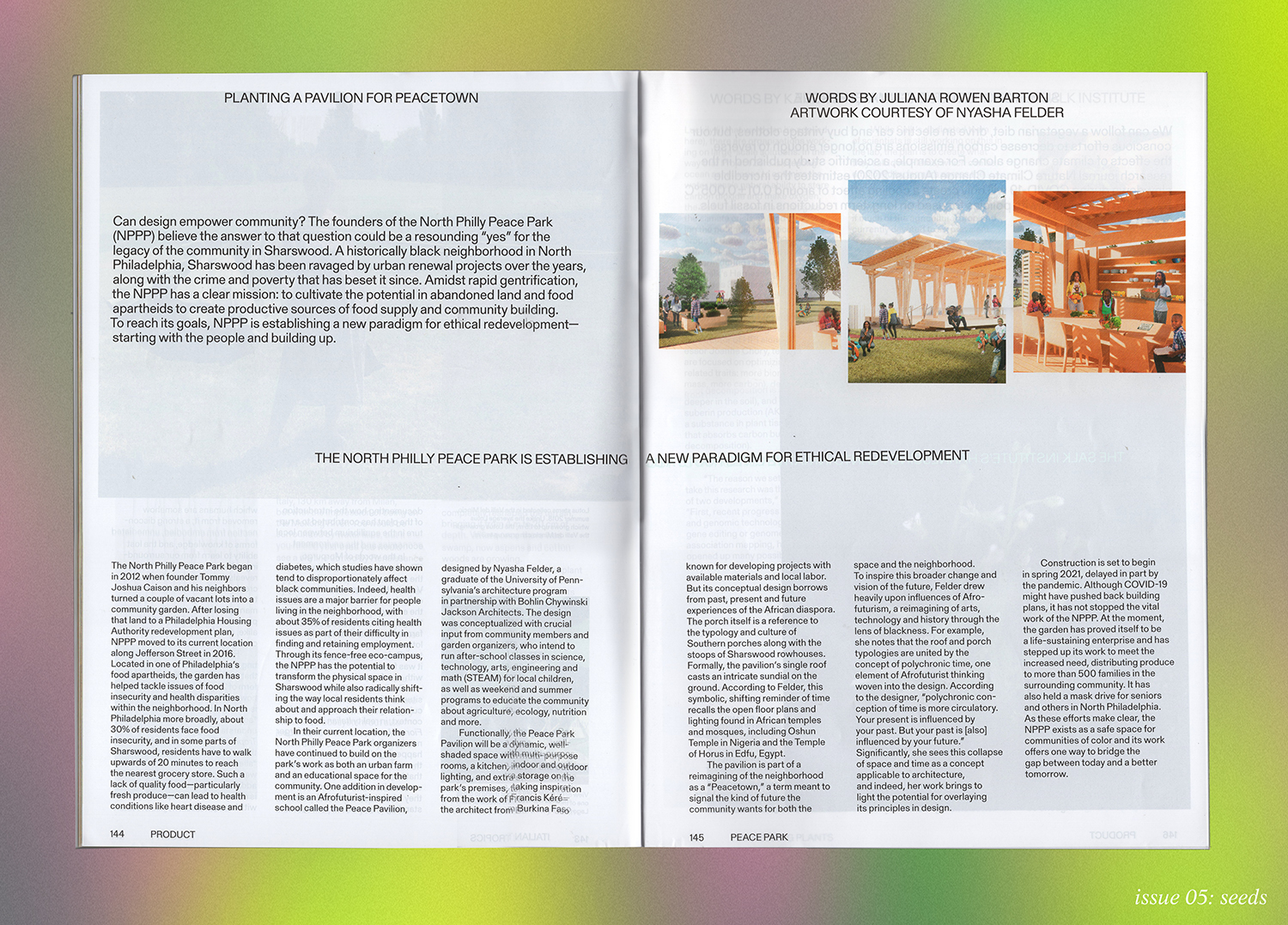

In their current location, the North Philly Peace Park organizers have continued to build on the park’s work as both an urban farm and an educational space for the community. One addition in development is an Afrofuturist-inspired school called the Peace Pavilion, designed by Nyasha Felder, a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania’s architecture program in partnership with Bohlin Chywinski Jackson Architects. The design was conceptualized with crucial input from community members and garden organizers, who intend to run after-school classes in science, technology, arts, engineering and math (STEAM) for local children, as well as weekend and summer programs to educate the community about agriculture, ecology, nutrition and more.

Functionally, the Peace Park Pavilion will be a dynamic, well-shaded space with multi-purpose rooms, a kitchen, indoor and outdoor lighting, and extra storage on the park’s premises, taking inspiration from the work of Francis Kéré—the architect from Burkina Faso known for developing projects with available materials and local labor. But its conceptual design borrows from past, present and future experiences of the African diaspora. The porch itself is a reference to the typology and culture of Southern porches along with the stoops of Sharswood rowhouses. Formally, the pavilion’s single roof casts an intricate sundial on the ground. According to Felder, this symbolic, shifting reminder of time recalls the open floor plans and lighting found in African temples and mosques, including Oshun Temple in Nigeria and the Temple of Horus in Edfu, Egypt.

The pavilion is part of a reimagining of the neighborhood as a “Peacetown,” a term meant to signal the kind of future the community wants for both the space and the neighborhood. To inspire this broader change and vision of the future, Felder drew heavily upon influences of Afrofuturism, a reimagining of arts, technology and history through the lens of blackness. For example, she notes that the roof and porch typologies are united by the concept of polychronic time, one element of Afrofuturist thinking woven into the design. According to the designer, “polychronic conception of time is more circulatory. Your present is influenced by your past. But your past is [also] influenced by your future.” Significantly, she sees this collapse of space and time as a concept applicable to architecture, and indeed, her work brings to light the potential for overlaying its principles in design.

Construction is set to begin in spring 2021, delayed in part by the pandemic. Although COVID-19 might have pushed back building plans, it has not stopped the vital work of the NPPP. At the moment, the garden has proved itself to be a life-sustaining enterprise and has stepped up its work to meet the increased need, distributing produce to more than 500 families in the surrounding community. It has also held a mask drive for seniors and others in North Philadelphia. As these efforts make clear, the NPPP exists as a safe space for communities of color and its work offers one way to bridge the gap between today and a better tomorrow.