Pre-order your copy of SEEDS, MOLD Magazine Issue 05 here for a pre-order price of $18USD. Expected ship date is March 22.

Who is part of our assemblage? Who is the other that co-determines or co-constitutes what is of importance? What provokes this pre-subjective process of communization? With this set of questions, the Futurefarmers, a group of diverse practitioners with a common interest in creating frameworks for exchange, have instigated projects over the past 25 years that sketch new narratives around soil and systems, and land and place, to destabilize logics of “certainty.”

In 2016, the Futurefarmers set out on a late-19th-century rescue boat to return seeds from an ancient grain field they established, back to their place of origin. This reverse migration of a set of seeds that ranged from the formal (seeds saved during the Siege of Leningrad from the Vavilov Institute Seed Bank) to the informal (Finnish rye recovered from an abandoned Norwegian sauna) charted an ancient route between Europe and the Middle East, which the project page describes as “combining human and non-human initiative by which wheat was domesticated from the wild, then slowly made its way through gifts, trade, winds and sea currents from the highly cultured Middle East to the barbarians of the north.” MOLD spoke with Amy Franceschini, founder of Futurefarmers, about the roots of the project, lessons from seeds about time and ritual, and the politics and poetics of rebuilding a grain-based society.

MOLD:

Starting with the Flatbread Society, how did it then evolve into Seed Journey?

Amy Franceschini:

Flatbread Society was a name that Futurefarmers gave to our working group toward a permanent public art project in a “common” area on the waterfront of Oslo. We chose a site within this new development that was as close to the waterfront as possible. We established an ancient grain field, planting seeds that were uncertified and had fallen out of production in the late 1800s and were then re-found in various places and brought back into production by farmers. We started with a collection of nine different grains. These grains were a symbol of the commons.

One grain is a Finnish rye (Svedjerug) that was grown by Forest Finns, who were a nomadic people moving around Norway up until the late 1800s when they were pushed out because of political reasons. In the ’70s, an amateur historian/archeologist thought, “This rye is pretty special. If we could find some we should just start to grow it again.” So they found an old sauna that the Finns had used to dry their seeds, got permission to take apart the boards of the roof, and found nine grains of rye. They planted them and grew these beautiful, tall, resilient plants, bringing them back into production.

We tried to collect seeds that have stories of resilience, returning them back to the soil and growing them in Oslo. As we were establishing this grain field to become a permanent farm, the harbor had this fleet of 1895 rescue boats that were established about the same time these seeds went out of production. They were built by the great boat builder Colin Archer, who also built the Fram, a boat that became famous for traveling the farthest north at one point in time. The Fram has played a role in our work in the past. It was interesting to discover that these boats are still around.

The project was gaining momentum and we got permission to build a permanent structure to go on this farm. We proposed to make a bakehouse, a traditional meeting place in rural towns. We worked with boat builders to build the structure fashioned after the Colin Archer rescue boats. During this process, in an informal exchange with our commissioner, we said, “Wouldn’t it be great to sail these grains back to the Middle East where they were domesticated and unravel their histories?” Our commissioner said, “Fantastic! Let’s do it.”

Almost the next day, we had a meeting with the captains who owned one of the Colin Archer boats. They owned RS 10 Christiania, which was the 10th number of this rescue fleet—Christiania is the original name of Oslo. It seemed perfect—a bit too perfect. To make a long story short, they agreed to do it. In our initial meeting they said, “In this journey, we can’t be stuck on time. There can’t be a schedule because it’s just not fun and it will become like a tourist project.” We wanted it to truly be an adventure and journey and be able to stop where we need to stop and consider that the wind will not always be in our favor. We needed to be able to move with the elements.

MOLD:

It’s interesting that Seed Journey situates seeds inside and outside of time, time being something that is quite flexible, i.e. seeds are not on human time. How did time play a role in the work?

AF:

Some of the seeds we are growing fell out of production in the late 1800s. Modern wheat was domesticated and selected until only the criteria that was good for the market was in place. The exciting thing about these ancient grains is that they have traits that weren’t selected out. They have this genetic memory still embedded in them: for example, if it rains heavily one year, a genetic or metabolic switch tunes them to how to exist in this situation. It also registers as a sort of adaptation to the changes in the weather.

They’re an archive of many things. They’re an archive of atmospheric change and a register of social change because farmers were choosing which seeds to grow based on their taste. Aesthetics plays a huge role in how seeds are saved and selected, which I didn’t know until I went to a gene bank. I realized one man gets to choose all the seeds and sometimes it’s about how beautiful a head of grain is.

Time, in another sense, came up with one of the farmers who helped us find this first ancient grain. When Johan Sward came to the farm, we talked about the farm as a museum without walls, and he talked about how he now gets these old (aka “farmer”) grains that have been saved in gene banks but haven’t been planted in 50 or 60 years. Once these seeds are planted, he gets them adapted to the current conditions and then sends a few of the seeds back to the gene banks, as a sort of update. He said to us standing amid a tall field of Finnish rye, “We don’t need museums to preserve varieties. What we want to do is grow them.” We carried that phrase with us in Seed Journey. Johan’s words really resonated with us as artists in terms of time and presence because we often do projects with museums where it’s sort of a Petri dish and things are presented under very strict conditions. We always try to push out of the museums and into the public realm where things are a bit more messy and you have to adapt in real time.

MOLD:

The quote you shared brings us to the “Seed Ceremonies” that became a narrative for bringing the seeds from the farms onto the boat itself. I loved these collective rituals that included farmers, artists, but also the stories themselves of the seeds. Can you speak a little bit about why this was so important?

AF:

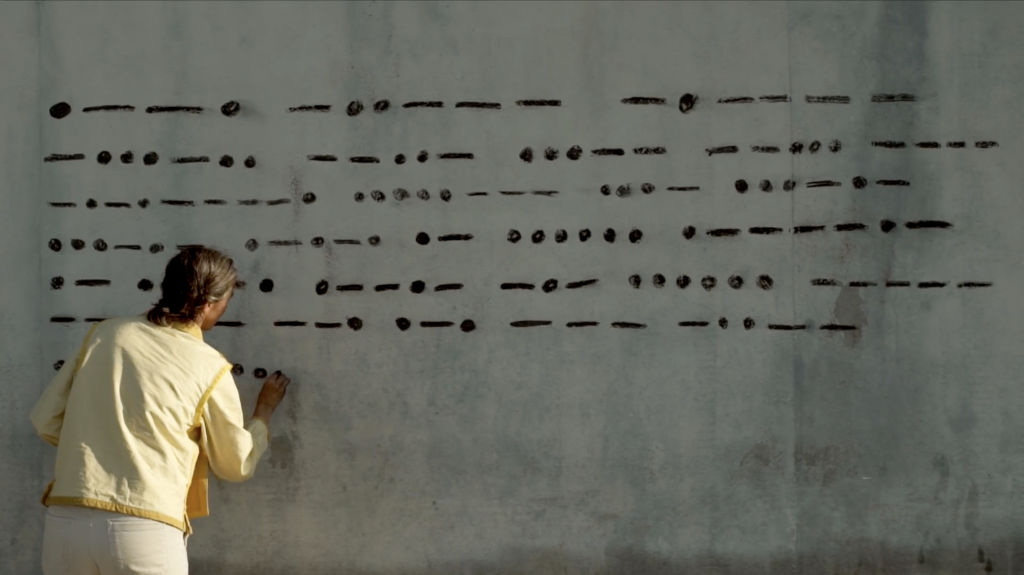

Ritual is kind of a heavy term and I try to shy away from it. I haven’t found the right word yet, but rather than just go to the farm and ask the farmer for seeds and trade seeds, we tried to amplify that exchange literally and figuratively. We would invite other farmers around the region and invite local media. We would also bring a message from the previous farmer to the current farmer and we translated these messages into Morse code and then into smoke signals. Upon arrival in a harbor we would send out the message of arrival and the notes from the farmers as smoke signals from this little oven we had on the ship.

These acts animate the imagination of the people we were visiting. Through the ceremony we would arrive as Seed Journey but also arrive as the poetics and aesthetics that came with it. We also had a suite of sculptures that came with us. The “Seeds of Time” is an hourglass with the Finnish rye inside that we carried all the way from Oslo—we would bring that to the table. It also had such a strong story that farmers and people were quite touched with this form of resilience.

We had a protocol for the “Seed Ceremonies.” One was to turn the time piece [on its side] so that it didn’t flow. It was a way of saying that, during this “Seed Ceremony,” our kind of mechanical time has stopped and a different time will unfold. It allowed us to be present with each other in a different way.

MOLD:

Seed Journey was called a reverse migration for the grains. This idea of returning seeds to their point of origin is something that continues to come up in conversations—the seed activist Rowen White calls it rematriation. The language is not only poetic but it’s also political. What are some of the themes that emerged from Seed Journey that you are continuing to explore in your work now?

AF:

The farmers that we met were mostly small scale farmers dedicated to getting ancient grains, or what they call “farmer grains,” back into production by getting these seeds out of gene banks and growing them. It’s something that surprised me, though quite obvious.

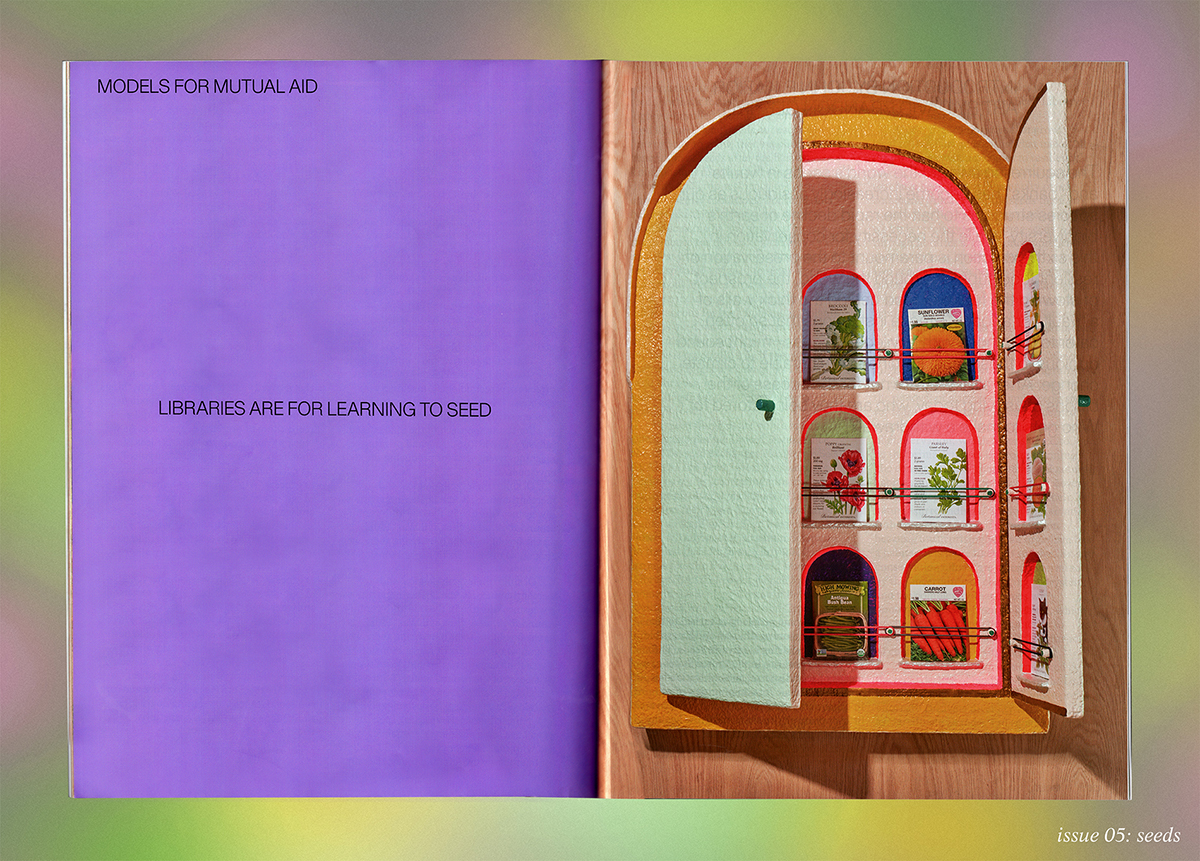

The other fact is that if we were to transition to a nonindustrial agriculture, let’s say overnight, we don’t have the seed stock to grow these non-certified seeds. We need to amplify production and get these seeds growing as much as possible. There are collectives and different networks that are working together in regional areas to get these very local grains back into production. What that looks like in Wales and England, and then Belgium, is creating regional economies to rebuild old watermills or windmills. The infrastructure of a grain-based society, once rebuilt, helps animate the grain farmers, the brewers and the bakers, and it gets people in a dynamic around the mill. It’s exciting because the establishment of regional economies seems ever more important right now.

We are often cautious when working with museums—we’ve questioned if museums are the right place for us to be working. But museums and cultural institutions were super important in terms of broadcasting our project, and we kept thinking of them as amplifiers.

MOLD:

Looking forward, what can seeds teach us about imagining a new paradigm for the future, a future food system?

AF:

I think hyper-locality, a hyper-idea of place because the seeds are really a portrait of a place on a wide span—socially, environmentally, geologically. Seeds demand different types of attention to what they produce and the conditions around it. If you’re growing seeds, especially the farmer grains, it demands a certain social contract to keep these grains and the knowledge connected to them circulating. The idea of having the seeds in the hands of many, rather than the hands of the few industrial corporations is where we hope the future will go. Many of the farmers we met told us that seeds are their social media.