This story is part of MOLD Magazine 02: A Seat at the Table, exploring how tableware and furniture can shape new dining rituals. Order your copy of the magazine here.

Looking beyond the horizon of this decade or even the next, the future of food and how we will eat it seems obscured by a curious paradox. On the one hand, humans possess unprecedented power to shape Nature to our appetites as science and technology deliver untold abundance, convenience and delight to the mouths of large swathes of the global population. However, our continued alimentary prosperity is simultaneously uncertain—ecological side effects of our success as a species place increasing strain on the delicate systems that sustain us. So an age-old arms race continues in the form of self-inflicted threats to human survival slowed only by our ability to interfere our way out of impending disaster.

London-based BurtonNitta is an interdisciplinary art and design studio that revels in grappling with the potential and limitations of human culinary evolution. The duo’s growing body of speculative work provides a provocative glimpse of possible worlds shaped by nascent scientific discovery, often through the lens of food futures and the rituals that could arise from these design objects.

One of their earliest proposals, Algaculture, points to a radical departure in the way we fuel our bodies. Without dwelling too much on the likely causes for such a shift (Ecological disaster? Sustainability efforts? Plant-based eating gone mad?), the project imagines a world in which humans have developed elaborate wearable tools that allow them to live symbiotically with algae. Inspired by a New Scientist article on ‘plantimals’ (animals, both naturally occurring and genetically modified, that live in symbiosis with plants, making them ‘semi-photosynthetic’), the designers Michael Burton and Michiko Nitta imagine a world where food production becomes reintegrated with daily human life. The head-mounted “Algaculture Symbiosis Suit” enables the wearer to feed the waterborne superfood with both the carbon dioxide from their own breath and sunlight—producing edible algal delights when nurtured sufficiently. The work also considers how such a food revolution would shape daily existence and includes a full-size solarium—in which the Algaculturalists would bask in nutritious sunshine—as well as audio recordings of future-fiction conversations in which people discuss where to catch the best rays and the politics of buildings blocking out precious sunlight.

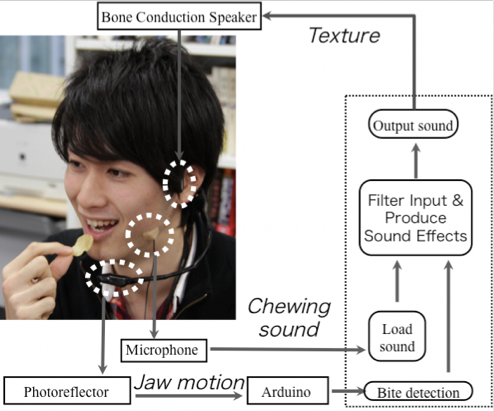

Another fascinating example, Gutscape, proposes a future in which eating becomes as much about augmenting our brains as sustaining our bodies. Informed by growing scientific understanding of complex nerve networks that link the human gut and the central nervous system (the ‘gut-brain’), the designers suggest that people might don devices—like their bizarre balloon-like “Vagus Nerve Stimulation Helmet”—to increase nerve connectivity between the gut and brain whilst dining. Gutscape enhances a diner’s eating experience and ameliorates one’s mood in a bid to cope with life’s daily stresses. As scientific endeavor and ecological uncertainty continue to accelerate, the speculative objects created by BurtonNitta confront us with the dramatic possibilities for shifting dining rituals and our relationship with food.