This story is part of MOLD Magazine: Issue 01, Designing for the Human Microbiome. There’s still time to order your limited edition copy here.

Consumption of mushrooms by humans is an ancient practice dating back at least 18,700 years to the Paleolithic “Red Lady” of Spain. Reaching even further back in history, one will find the role of fungi in making mead, the first food products intentionally crafted by humans—simple honey wines made by fungal yeasts. Fungi continue to occupy an ever-expanding role in the culinary and medicinal landscape. Leveraging complex ecosystems, fungi act as nature’s greatest stewards and healers—powerful and ancient allies with whom modern humans have only begun to recognize as critical to sustaining all life.

To the elites of ancient Egypt and Greece, mushrooms and truffles were considered broma theon, “foods of the gods,” so revered was their potent flavor and nourishing effect. In the East, mushrooms were central to the health and longevity of the Taoist immortals; in Traditional Chinese Medicine’s (TCM) foundational texts written millennia ago, the Reishi mushroom is recognized as the “king of all herbal medicines.” Above Ginseng root, Reishi is seen as the most potent of all stress-reducing and balancing medicines (adaptogens) in TCM. Carved into the entrance to the Forbidden City in Beijing and woven into the robes of emperors, this mushroom’s form long stood as a symbol to the ancient Chinese of vast power and enduring strength.

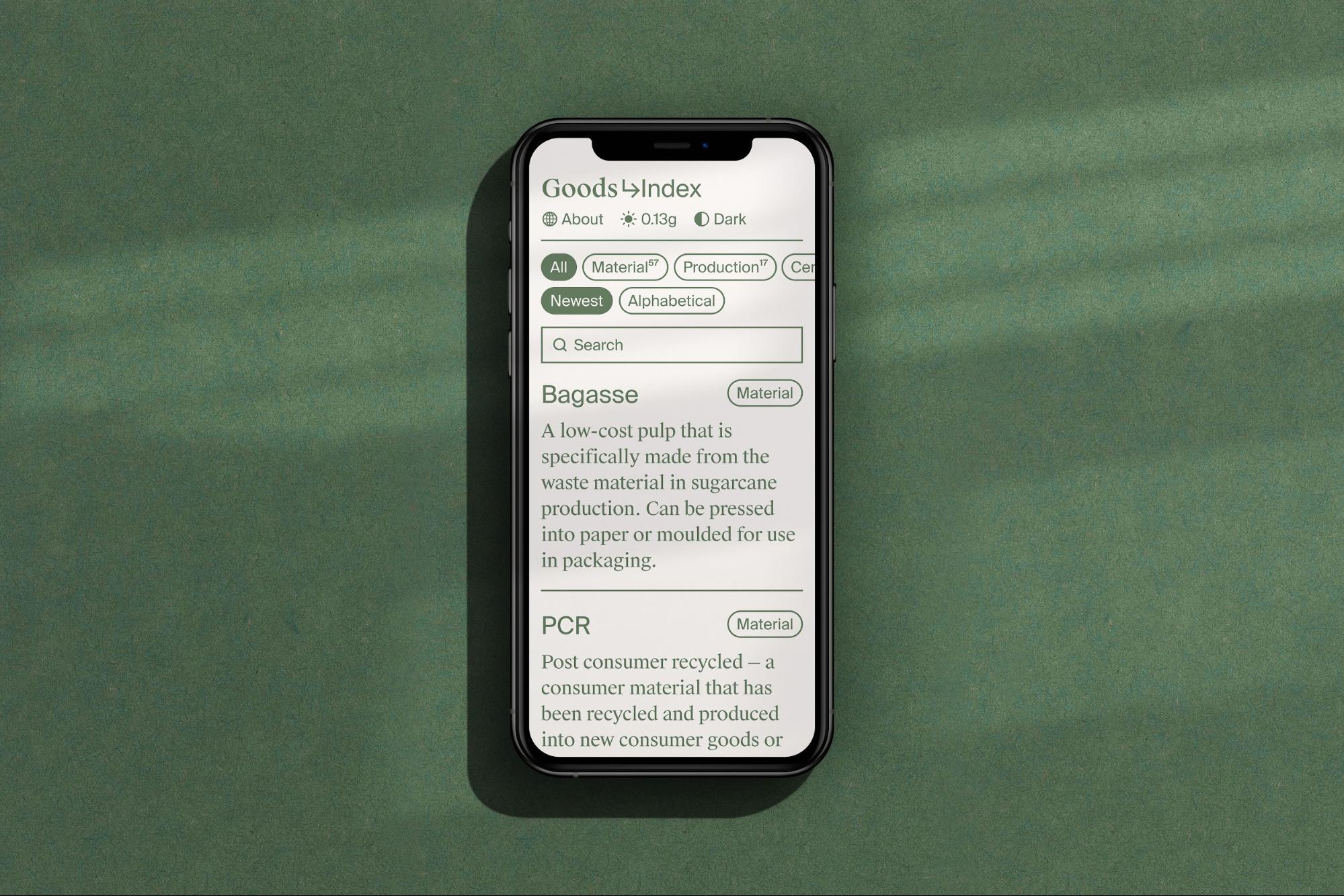

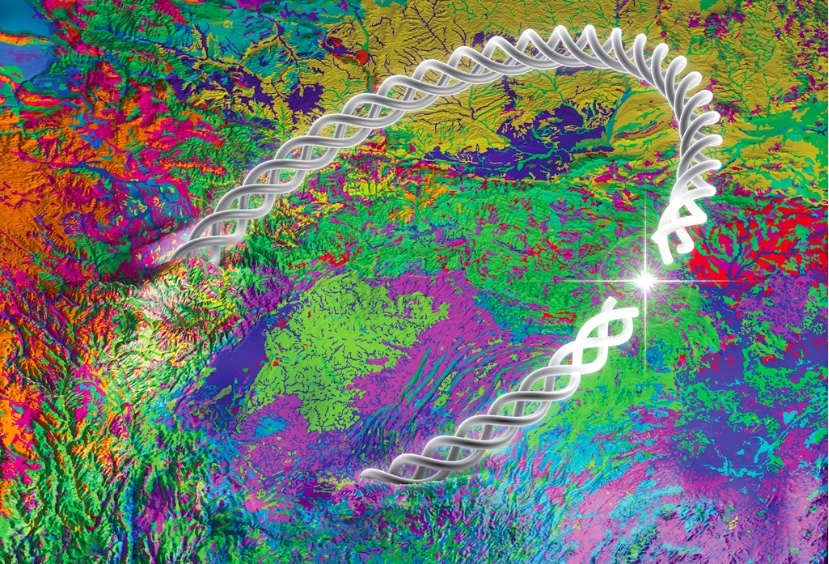

Artwork by Eric Hu for MOLD Magazine

Artwork by Eric Hu for MOLD Magazine

Along with mushrooms, various molds and yeasts have long been appreciated for their nourishing qualities. Molds are celebrated for their ability to enhance the flavor and nutritional value of plant matter, an appreciation found in many traditional fungal-dominant ferments. For generations, Aspergillus sojae has been grown on barley and rice to create koji, a moldy grain product used in the production of saké and the umami-rich condiments of miso, soy sauce and tamari. Similarly, producers of wine—itself a product of yeast—often spray grapes with the mold Botrytis cinerea to produce the “noble rot” that concentrates the fruit’s flavor, thereby creating the rich flavors of botrysized dessert wines. The alternative meat product tempeh is likewise created by growing Rhizopus oligosporus on grains or legumes over the course of a single day. During this time, the mold ferments the ingredients to enhance their flavor and nutritional value while also knitting them together into a protein-rich patty.

In all of these moldy foods, the fermentation is performed by the fungus’ primary tissue known as mycelium. Mycelium is what comprises the bulk of most fungi—it’s the white, web-like stuff commonly found beneath old logs in a forest—it’s the same tissue that lies beneath the colorful spores of molds and also the tissue that is condensed into the macroscopic structures we call mushrooms.

In all environments, mycelium critically influences the nutrient access and overall health of plants and animals. Fungal mycelium can readily digest complex animal and plant matter into simple sugars and proteins, while simultaneously releasing trace minerals from rocks and clay through the use of strong acids. Additionally, below ground mycelial networks control the movement of nutrients throughout environments, thereby influencing which plants and animals can grow in a given habitat. Nearly all wild plants are fed by fungi that associate with their roots and move nutrients between plants. The aboveground tissues of all plants are permeated by hundreds of trillions of fungal colonies that provide disease, drought and insect protection from inside.

Despite our wealth of knowledge on the importance of fungi on plant health, their positive influences on animals remains largely unknown. We know that in ruminant animals like cows, fungi are responsible for the fermentation of plant matter in the animal’s rumen, creating the cud that is re-swallowed by the animal to digest in its true stomach. Likewise, yeasts in the guts of beetles—the world’s largest group of insects—are essential for the digestive prowess of these insects and may influence their overall health. In humans we know that along with the bacterial microbiome of our mouths and digestive tract, there are also distinct communities of fungi—mycobiomes— that shift in population based on our diet and other environmental influences.

These internal (endosymbiotic) fungi may very well influence human health to profound degrees that have yet to be fully recognized. Even if this influence is minimal when compared to plant-fungal relationships, it is still likely to be instrumental in our digestion and human immunity. As our understanding of how the population, diversity and integrity of the human mycobiome is further refined, how might fungal supplements, or promycotics, of the future be designed to positively influence the symbiotic fungi inside our bodies?

Artwork by Eric Hu for MOLD Magazine.

Artwork by Eric Hu for MOLD Magazine.

Though our understanding of the mycobiome is only now developing, there are various ways to bring the health benefits of fungi into our lives. Along with the foods noted above, one area that has largely remained unexplored is the consumption of mushroom mycelium as its own unique, nutrient-dense food. Just as the mycelium of beneficial molds can be grown on grains, so too can the mycelium of mushrooms be grown on a wide range of products—from herbs to grains and legumes, animal tissues to mineral sources, and their innumerable combinations—to create products with a range of flavors and nutrient profiles and, more notably, an abundance of medicinal compounds found only in mushroom mycelium.

By growing mushroom mycelium on edible ingredients, food producers can design novel products with unprecedented health qualities. This high-value fungal food has largely gone unexplored due to the slow development of reliable and inexpensive mushroom mycelium cultivation practices—processing methods that are now more readily available, yet unknown to most food producers. In the field of industrial design, companies like Ecovative are biofabricating mushroom mycelium into eco-friendly, functional products from packaging to construction panels. In fashion, MycoWorks is growing a sturdy, animal-free “leather” using the mycelium of Reishi. A future of mycelially-enhanced foods is likewise within reach. As awareness around fungi increases in the coming years, demand for fungal products will need to be addressed across a range of untapped industries, setting the stage for a new era of wellness in the age of fungal food-medicines.