Methods & Provisions is a series documenting the memories, rituals and soundtracks of people who love food.

In New York-based artist Wen Liu’s practice, crafting nature-inspired ceramics are a way of surfacing that which is lost in translation between language and the corporeal. Originally from Shanghai, Liu’s recent series of sculptures, titled Inarticulate Trace, examine how we communicate pain, grief, transformation, and healing, embedding herbal medicine prescriptions in ornately modeled frames. Liu draws inspiration from processes found in nature like molting or fire, emulating these in her own art-making practice to create works that bridge between our natural worlds and that which language cannot reach. In our conversation at Liu’s studio last month we talk about rituals of herbal medicine, what draws her to mold-making across her work, and the routines that ground her practice.

Isabel Ling:

Tell us a little bit about your background and your practice.

Wen Liu:

I graduated from The Art Institute of Chicago and stayed in Chicago a few years after graduation. Around two years ago I moved to New Mexico for a year-long residency in Roswell. It’s been a lot of moving lately, and I finally moved to New York last August and am settled here.

IL:

Oh, interesting, alien territory.

WL:

Yeah, it was an amazing year. I could focus on my work and was able to try a lot of different things. One benefit of the residency is that you have a solo show in a museum, so you have something to work towards. Making mistakes is an important part of my practice, so it was nice to have a long term goal, but still be able to play around and experiment. A lot of the works I am making now are evolutions of that solo show and extensions of what I was exploring in New Mexico.

I started working with herbal medicine right after my father’s passing. He used to tell me that I was born because they had been drinking herbal medicine for a year. So when I heard that I was upset and thought, ‘Oh, I wasn’t created naturally.’ [laughs] But, after growing up, I realized this is the most natural thing.

I have a long history of drinking herbal medicine. As a kid I had a very bad appetite and wouldn’t eat. My mom needed to chase me to feed me, I remember the medicine being very bitter but it was always followed by a sweet candy. That’s my recollection.

IL:

Was it presented to you as tea?

WL:

Yeah, they give you a huge paper bag with a combination of different herbs. You boil it and drink it three times a day for a week, and the doctor will adjust when you see them the following week. Do you have experience drinking herbal medicine?

IL:

I don’t have experience with seeing a doctor or drinking tea. But my family is from Hong Kong, and my one memory with herbal medicine is drinking this soup made out of turtle shell at a medicine shop there to help with acne in high school. Because turtle shells are cooling and acne is an expression of a heat imbalance.

WL:

Well, when you go to a doctor of Traditional Chinese Medicine it’s a very interesting process. You don’t need to do any lab tests. They just look at you, and diagnose you off of the feel of your pulse and how you describe your symptoms. How accurate the treatment will be really depends on how well the symptoms are described. So I felt some frustration, because it’s difficult to articulate the pain I was experiencing, and it’s hard to measure my pain up against the pain described by others. This experience reminded me of the frustrations when using English as a second language. Similarly, I need to understand what people are saying in a second language, measure against it, and use it to express myself.

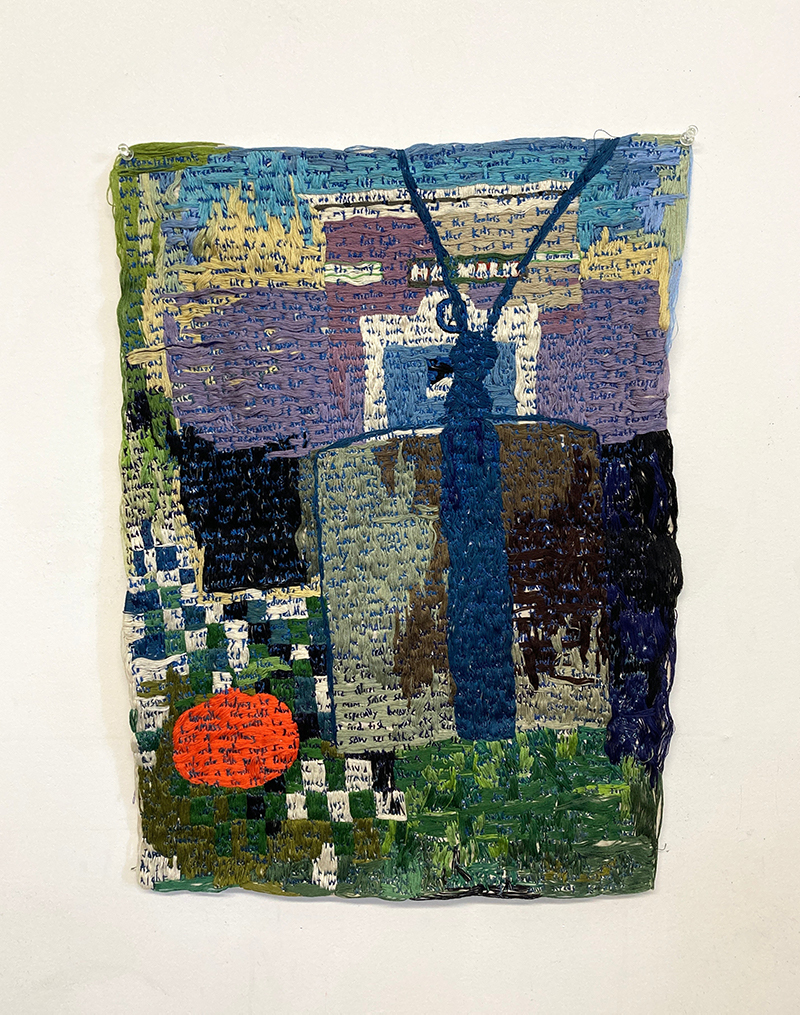

So I decided to embed and preserve a dose of my prescription in sculpture as a representation of the frustrations of inarticulation. I call these works Inarticulate Trace. I am always joking that if someone knows herbal medicine, they can see my work and decipher that I have insomnia [laughs].

IL:

I’m curious about how these like ceramic forms that you’ve encased the medicine in reflect the prescription as well.

WL:

I got inspiration from stained glass windows and incorporated bone (the structure of the body) to make the structure of the sculpture.

IL:

Tell me more about your artmaking process, what goes into one of your pieces?

WL:

I start with ink sketches. I can do it very quickly and it’s very satisfying. I create these ink drawings and fold them in half so they become symmetrical, like Rorschach tests.

When I do it over and over again, I start to see the different forms and get inspiration from them.

When I want to develop a sketch, I will start with a clay sculpture and make a mold.

IL:

What draws you to molds?

WL:

I think mold making is like the molting process in nature. Insects, spiders, snakes and scorpions all shed their skin so they can grow bigger and stronger. So after making a mold, I press clay into the mold to make the sculpture.

IL:

A lot of your sculptures evoke organic forms. What is the influence of nature on your work?

WL:

I love being outside. I made a piece where I connected tree bark to a pine cone, representing my relationship with my dad after his passing. As a traditional Asian parent, we were not very close. I don’t remember him holding my hand growing up. But whenever I go for a walk in the woods, if I see a pine cone, I always pick it up. I love the feeling of it in my palm.

When my dad passed, I wasn’t able to see him – I was here in the U.S. and didn’t have anything to remember him by. I had a mold of his hand that I made a couple years ago when I visited. I didn’t plan to use it for anything particular. When I brought it back home, it broke into several pieces. After repairing it, I pressed clay into our palms and made two pine cones, connected by a slouching tree bark. And [in Chinese] we always say, ‘Fallen leaves nurture the tree roots for the next generation.’ So I made that piece for us. I always get inspiration from nature. I think nature is the greatest artist.

IL:

You talked earlier about language’s role in your work, but in a sense, you are creating your own language as well here.

WL:

I think it’s a very nice way to put it because I feel like sometimes I cannot say it in words, so I make works. There’s something language cannot reach. For example, the prescriptions are important because I don’t think pain is shareable. It’s hard to describe pain. And it’s hard to understand until you feel it. I have always thought that language has a limitation.

IL:

I’m interested in what drew you to ceramics as a whole though. Like, do you have a point where you remember being drawn to this medium?

WL:

I was in the sculpture department [in school], clay is the first material I found familiarity with. I love that the material has a simultaneous response to my body.

I started to seriously work with clay after graduate school, and wanted to use fire as an element in my work. I remember when I was very little I went to a small town with my family. There was a neighbor who passed away and the family hired a group of people to make a house out of paper. It was human scale. There was no printer or computers and every decoration was made out of paper. They made motorcycles and embroidery blankets by cutting the shapes out of paper. And then they burned it all. They gathered the family and the relatives, burned everything they made out of paper in honor of the dead, and had a ceremonial dinner afterwards. People believe that through burning, their loved ones can use these items in the afterlife. I felt like that was so beautiful. It’s maybe a little superstitious, but I love the idea of people investing their money and time and effort, and burning it as a way to relieve themselves. To grieve.

Every culture has a different understanding of fire. Ceramics use fire. Clay changes after firing. I am interested in absence. What is burned leaves imprints and what is left is a mold.

IL:

Earlier you were speaking about the limitations of language and what gets lost in translation. From your experience, I’m curious to see what different ideas of health get lost between Western and Eastern medicine.

WL:

They both have their good and bad. I think they should work together as a team, I go to both. I’m interested in the balance that could happen between the two.

IL:

Are there any rituals or routines you incorporate into your practice?

WL:

The process of mold making is like a ritual, especially when the material is time-sensitive / has a pot-life. Need to be very strategic and focused.