Methods & Provisions is a series documenting the memories, rituals and soundtracks of people who love food.

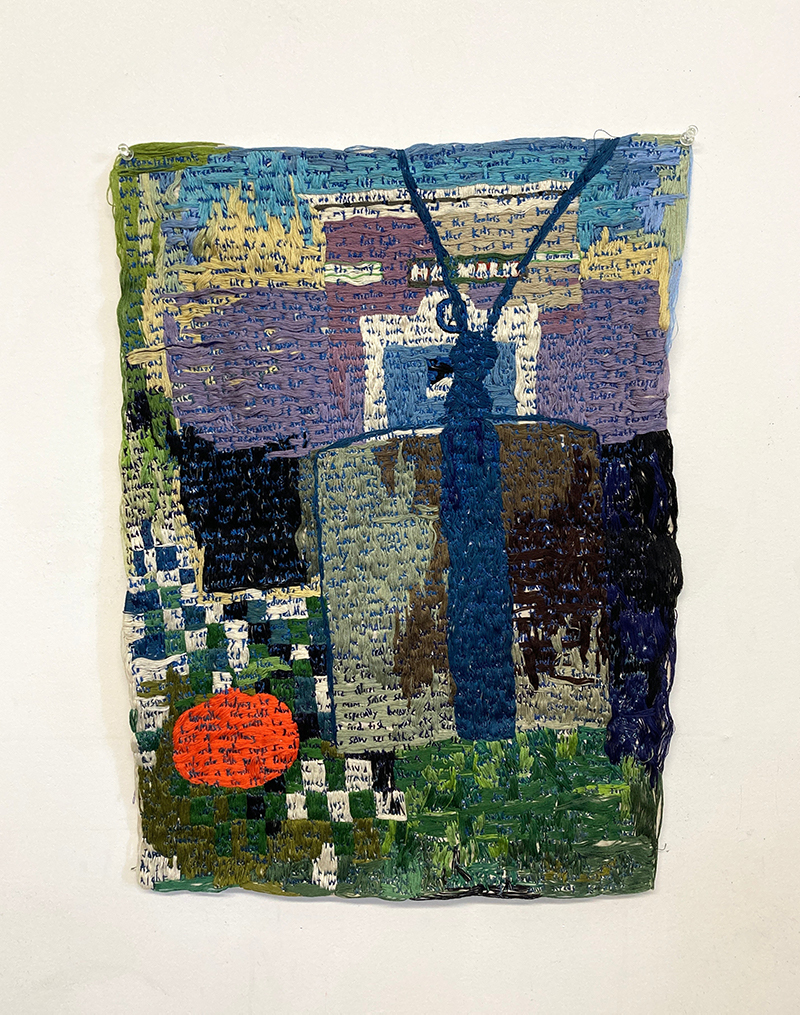

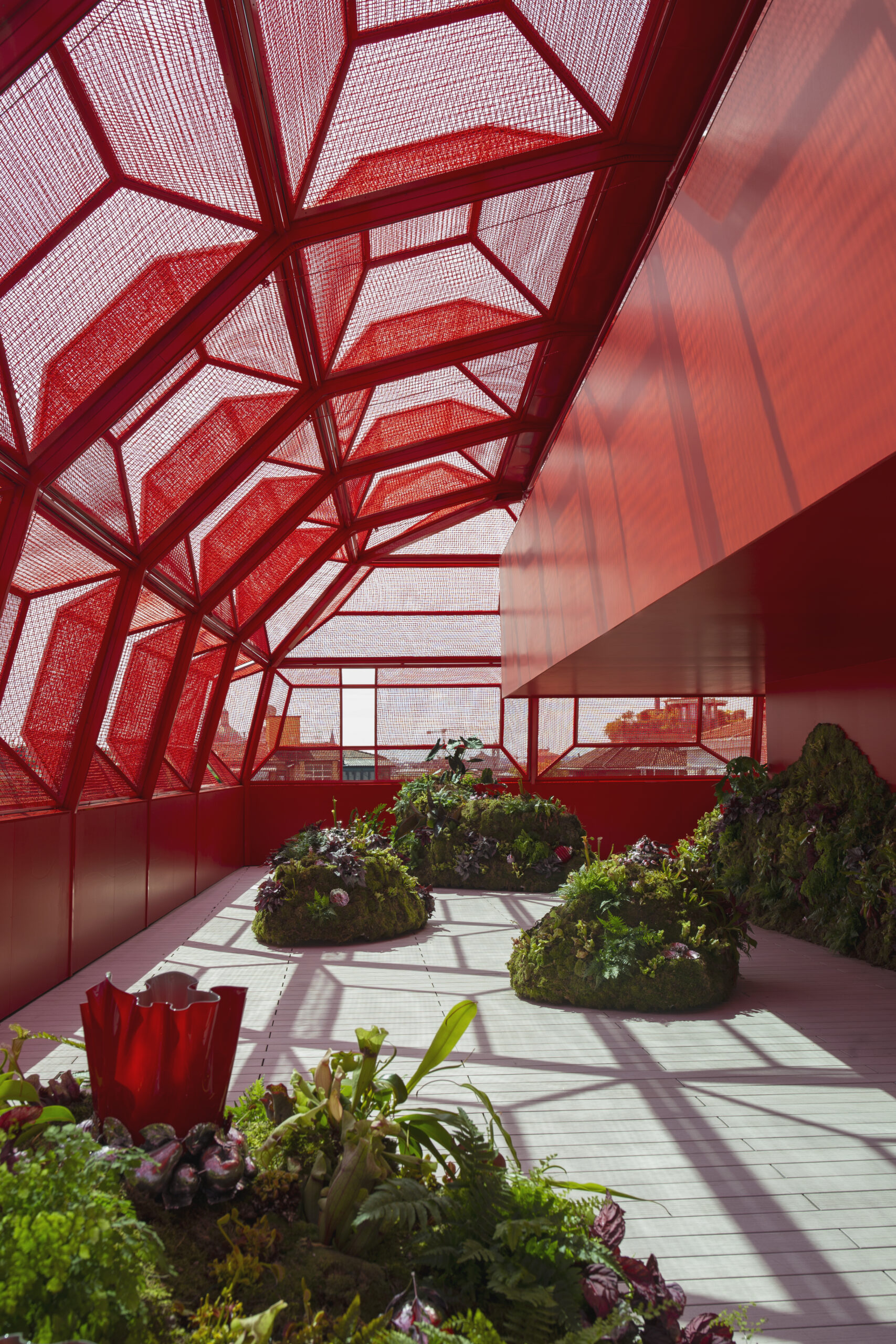

Lily Kwong creates portals of communion with the natural world. Sometimes this looks like a shock of red blooms meandering across the main thoroughfare of a bustling Taipei night market, in another instance, it can look like rugged, mossy hills rising out of Grand Central Station’s tiled floors to envelope harried commuters. The botanical artist and landscape designer draws from the unexpected, carving out space and time through her installations and facilitating moments of reconnection with nature in the otherwise dense, urban environments she often works within. Most recently, Lily designed the New York Botanical Garden’s Orchid Show, constructing a lush landscape to reflect the story of her own family heritage. In this conversation, I spoke with Lily as she was preparing to install an exhibit of carnivorous plants on a rooftop in Milan. We talk about the power of native plants, what it means to be a landscape designer in the midst of a climate crisis, and how ritual grounds her plant practice.

Isabel Ling:

You’ve been working with plants for more than a decade now. Tell us about how you came to your practice.

Lily Kwong:

One of the great privileges of my life was that I was born essentially surrounded by the redwood trees of Muir Woods, which are the tallest trees in the world. They’re these ancient giants and have this cosmic, powerful, and very spiritual resonance. They were really the backdrop of my childhood. You know, Muir Woods has been called a cathedral — the way the light comes through the trees. My science and art classes were always outside in the woods. I started my first nature club in first grade building forts and foraging for plants. I worked with my grandfather at the farmers market, who would volunteer his time every Sunday.

Then I moved to New York when I was 18. Going from a place that was wild and full of nature to a really urban environment, you become a bit disconnected from your needs. At that time I was so enraptured with culture, art, fashion and design and I just got so far away from that wild, inner child. In the end, I ended up at Columbia, studying urban design, where it was more focused on urban theory and policy. And then, just out of pure coincidence, my first job out of school was at Island Planning Corporation, which is an urban design firm that happened to focus on landscape. The company specialized in working in really remote, very logistically challenging areas, so we were working in the Bahamas, and in Gabon in Central West Africa, Careyes, and more. As soon as I got out into nature again, into the woods, my whole body and spirit came alive again. I just felt so much more present and so much more myself. A lot of the more neurotic side effects of living in a city, like insomnia and anxiety just kind of faded away when I re-synced with the rhythms of the natural world.

When I left the company to move back to New York, a lot of my community and world in New York was very creative. So even though my intention was to start a traditional landscape design firm, the type of commissions that I was getting were more like ‘Here’s a warehouse space and we’re doing a fashion show and I want a ton of plants.’ Through my community, I started developing this kind of non-traditional approach of using plants as an artistic medium, really merging plants and culture in a unique way.

IL:

Across the past 10 years so much has changed in terms of climate and how we relate to our natural environment. Restoring harmony between ourselves and our environment seems more important than ever. How has that affected your approach as a landscape designer?

LK:

My mission is to reconnect people to nature. The mission hasn’t changed since day one, it remains my driving purpose. But I do think the effects of the climate crisis are so much more visceral and so much more intense [now]. These things we’ve been talking about since the beginning — sustainability and climate – are much more present in the public discourse now. Now it feels like a very mainstream conversation. So there’s a lot more resources and collaborators available to me, which I find really exciting.

Honestly, it was the lockdown that really affected me. All of my major public art pieces had gotten put on hold. I was suddenly in Los Angeles, staring at my backyard. And that became my project — learning about the immense benefits that native plants can provide to support habitat, restore ecology, reduce water waste, and create a sense of place. I became intensely passionate about native plants and their power to heal our landscapes. And so, that was something that I was always exploring, but has been much more at the forefront of what me and my team are doing today.

IL:

Yeah, I’m curious, how has the material nature of working with plants changed for you as you became more climate conscious across your practice? Like, what does the climate crisis look like for someone who is stewarding plant life across the world in this way?

LK:

In terms of our research and sourcing process, we’ve always had a policy of developing an exit strategy post-installation. We try to use sustainable materials where possible, and after an installation — especially if it is a temporary installation or exhibition — we find a second home for the plants, whether it’s a community garden or gifting them to the public.

Right now, we’re working on a piece in Milan for Salone and both of the fabricators that we’re working with are taking the plant material back and taking the built materials back to their fabrication studios to reuse for their next projects. So we really try and think of the whole life of the project. For this Salone show ecosystemic designer Lily [Tagiuri], came up with this genius idea to do a survey of carnivorous plants. Since the piece is only up for a week, we have the flexibility to do this incredible exploration of this one type of plant that’s not necessarily native to Milan since we’re not affecting the local ecology. If we’re working on a permanent piece, we really prioritize working with native plants and creating habitat.

Another approach is how we build knowledge. I personally always start at nurseries, I find nursery men, women and horticulture people to be the most wise and generous people. I’m always humbled by how much wisdom they’re willing to share with us as artists and designers, and how invested they become in our projects. And I find that people who run nurseries and especially native plant nurseries, they’re the ones that have the on the ground knowledge that is going to elevate a project to the next level. We can do research online and in books, but it’s the people who are handling plants day to day and have dedicated their lives to horticulture that will give us the inside information on what’s best adapted to that climate. How are certain species handling urban traffic or changes in habitat due to climate change? Or any tips of the trade — I find it’s really horticulture folks and nursery people that give you the keys to that information.

IL:

Right, I wanted to learn more about your creative process and the tons of research that must go into it. How do you execute an idea into a landscape?

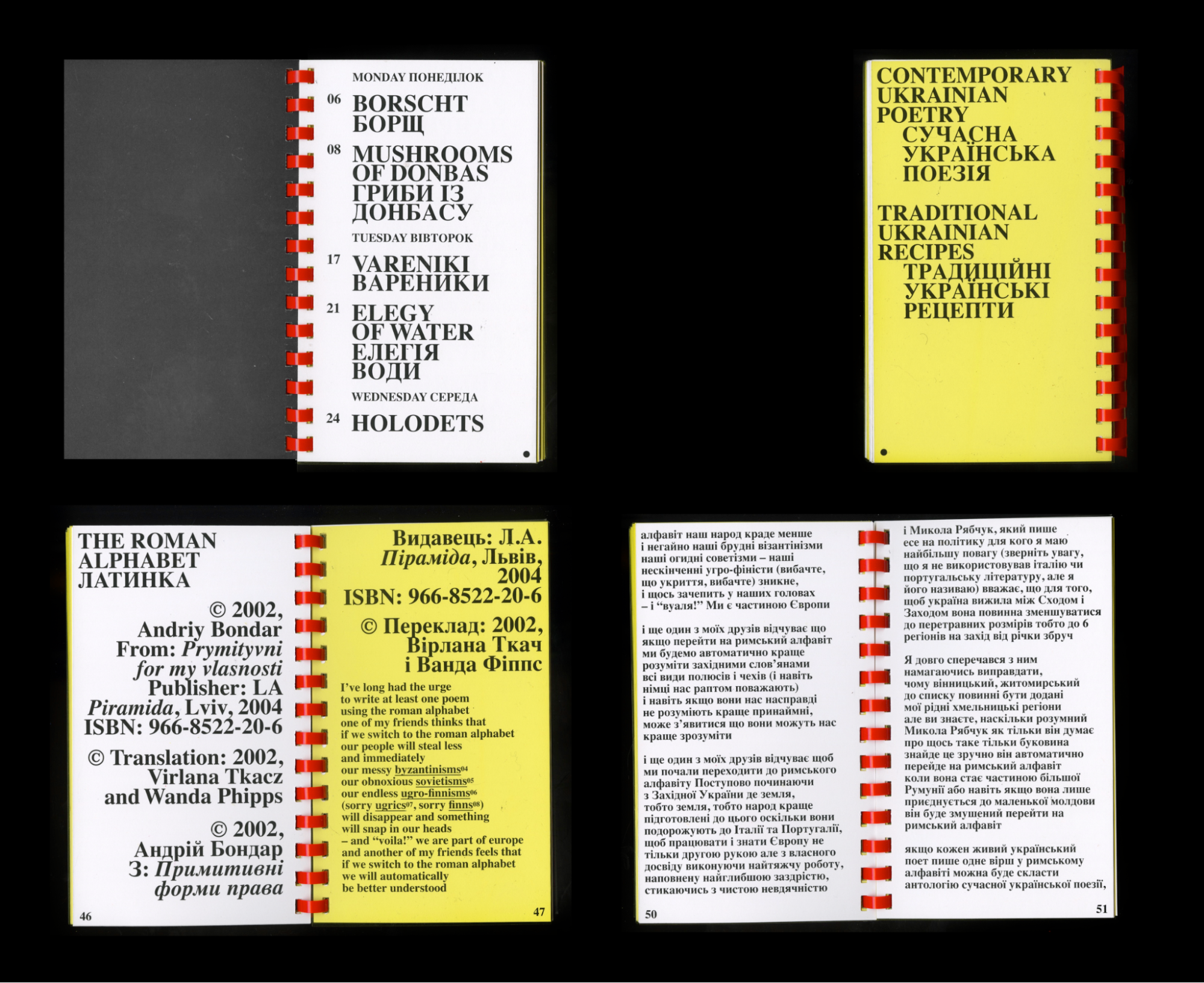

Well, here, I really want to call out my collaborator Lily Consuelo Saporta Tagiuri and my project manager Shannon Lai. Lily has an academic background and is an industrial designer that loves doing deep dives into research. As a result, a lot of our research is not just on the biological and botanical properties of these plants, but also the cultural information that surrounds them — especially in the myths, traditions, and folklore. Something I learned from our experience with the New York Botanical Garden is how powerful narrative is. As humans, we are drawn to stories. For millenia across all human cultures, plants have always been at the center of so much storytelling. So uncovering some of that ancient information and bringing that to the forefront of our projects is a really joyful process for all of us.

Then there’s Shannon, who brings a background in urban farming, she was a project manager at Brooklyn Grange and brings a really strong hands-on tactile experience. She’s the one going to the nurseries, talking to plant people, amassing local oral information. We do a pretty robust site analysis where we’re looking at the site conditions, the sun shade, the climate, seasonal cycles, what view corridors there are, and then themes emerge from brainstorming and sketching. And then a concept takes shape and keeps getting refined in collaboration with whoever our partner is, whether it’s an institution or a brand, or a client. Then, we start sourcing and fabricating our vision.

IL:

Do you have a dream project?

LK:

During the lockdown, we launched Freedom Gardens. It was a project from our studio between me, Lily, and Shannon that was a way to share open source information, largely based on Shannon’s many years of working as an urban farmer on how to grow food. During the pandemic, food inequality came to the forefront. Even though our centralized, unjust food system was already very volatile. The project was a way to ask ourselves how we could be of service to our community. The result was very beautiful to watch, first-time growers came together with us to start their own at-home gardens using our educational resources. It was very empowering to see people grow their own food as a way to regain autonomy and participate in a practice that is so central to human existence. So, I would love to build an urban farm that is founded on mutual aid, public access, beauty, and knowledge sharing. A lot of that work is already happening in LA with incredible leaders like Ron Finley or Jamiah Hargins. Realizing Freedom Gardens as a physical project feels very connected to our values and vision for the next step for our company.

Elevating the mundane to the sacred is something I want to explore more in my work

IL:

Do you have any rituals or routines that you incorporate into your practice?

LK:

The New York Botanical Garden show was the first project where I deeply incorporated ritual into the piece and I envision growing this even more. I have a very dear friend and collaborator who’s installed many projects with me, Sandra Sears, who studies plant medicine and indigenous cultures. This was the first time that I flew her out specifically to do a ritual, and it was right before we opened the NYBG piece. It was so moving and made me realize that it’s something that I want to do for all of our pieces. Not only infusing a piece with our intentions, but elevating the mundane to the sacred is something I want to explore more in my work. Sandra has also led a couple of cacao ceremonies at my house, for friends and family. Cacao is so powerful, it has incredible abilities to detoxify the system, and boost immunity and energy flow. It also serves as a creative and meditative tool. I find that I can go much deeper in my artistic practice after we’ve done the cacao ceremony, so I’ve asked her to lead them for my team and my community. I would love to embed these rituals centered around plants in a thoughtful and respectful way into our work in the next chapter.

As a part of the Methods & Provisions series we always ask our interview subjects to provide a playlist of the music that soundtracks their practice. For her contribution, Lily has included a playlist curated by her best friend Jessica Cross (@flyhendrix), whose playlists she often listens to in the studio.