Methods & Provisions is a series documenting the memories, rituals and soundtracks of people who love food.

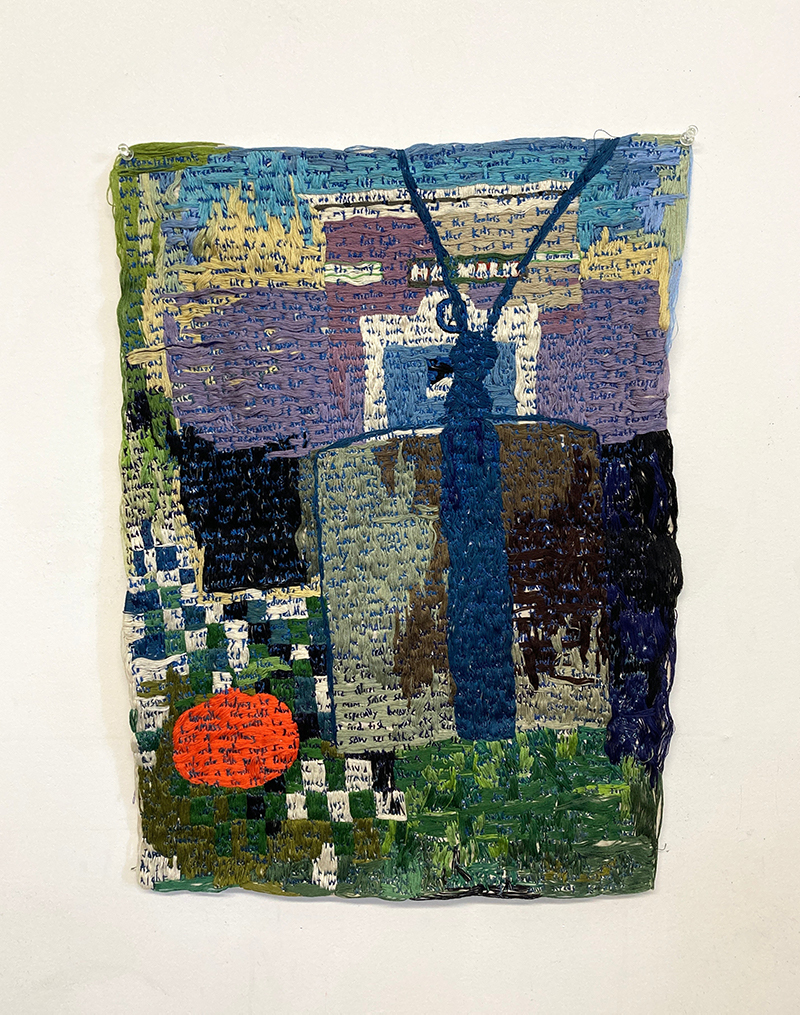

quori theodor’s medium is mess. For the artist, writer, and experimental chef, disorder and decay are an opportunity to investigate questions around why we eat and how. Their most recent endeavor is Gnaw, a multisensory exhibit that transforms Performance Space’s gallery into a kitchen, diner and stage. Here, the delectable and the disgusting intermingle, encouraging visitors to come closer, and peer into the mess that is gender. In Gnaw, food is designed to defamiliarize. Magnified, fermented and leaking, food becomes a cheeky challenge to conventions of normalcy and desire. On view until June 15th, the space has provided a home for a spate of programming that has ranged from Asian American farming collective Choy Commons’ Spring Opening, to a laughter meditation featuring transcendental musician Laraaji, to a slimy performance from experimental collective Young Boy Dancing Group. Earlier this month quori and I posted up at a booth in their installation to talk about carving out institutional space for community, digestion as performance, and the freedom offered within the structure of rituals and routines.

Isabel Ling:

For Gnaw, your medium is, in some ways, space and the different ways it can be used and adapted. How has the installation turned out differently than what you imagined it to be?

quori theodor:

I think it is working in a lot of ways how I had hoped it would. It really is a space people use, which has been a nice surprise. Social practice is such a big part of what I do, but so rarely do installations inherently get to facilitate that in this way. So we’ve had [programming] stuff, but it’s open to the public usually. People are even studying here. Activists have used it for meetings. That was really something I was trying to encourage, especially with how the year has unfolded. But overall, both the programming and day-to-day usage of the space has been really flexible, and that’s been a real gift to see in action.

IL:

I first learned about your practice when I interviewed you a couple years ago for the work you were doing through the queer cooking collective Spiral Theory Test Kitchen. Even then your practice was rooted in this social practice you speak of. I’m curious to know how it has evolved in the past couple of years.

QT:

I definitely think that it’s congealed a lot more—especially in the sense of its theoretical underpinnings and poetic trajectory, as well as the food itself, and how those components come together to make a social environment. I don’t feel that I draw as heavily on food customs, I think because I’ve learned more about how people respond. Like, the works have stopped having to rely on what people bring to the food or its functionality as heavily.

Spiral Theory always did have this kind of multi-component flexibility. So I have definitely brought that into my solo practice with food. Currently, I’m writing a lot, publishing, and creating visual works, in addition to the more performative stuff. I also work in fashion as a creative director sometimes. In a broader sense across these disciplines, I’m interested in giving food within an art context more room to breathe. [I think] to not include food-based work in a canon of, like, art history, is an oversight, not only because lots of artists have already worked with food but also because food is an extremely effective and affective medium that is really rich.

In terms of how this can look for me, this can be one night performance-based installations, a lot of times surrounding a table or incorporating food. They usually are theme-based or have something to do with a the setting or publication I’m working with, which I think is really fun too. The themes can range from sabotage to the political subjectivity of animals to niche fetishes.

IL:

You are also an educator, can you tell me a little bit about how that has shaped Gnaw?

I think teaching has been a huge benefit. For me right now it’s kind of a test site for a lot of my performance work. [In my practice] I’m moving a lot more into performance in a more explicit way. And, leading movement workshops has been really helpful. I’ll provide food-related prompts to these dancers and non-dancers, and see where they take it.

IL:

What are these prompts?

QT:

A broader prompt for some of these movement workshops is the question: is digestion (already) a dance? We have these internal, non-voluntary systems involved with digestion. But the general idea is that food is an internal process, but how can we externalize that which is internal? And there’s also social customs around eating, of course. How you sit at a table, and how you use a fork or knife, or choose not to use a fork or a knife, that is also movement practice, a choreography.

IL:

Right, it reminds me a lot of etiquette, and the performance of dining.

QT:

Totally, it’s a lot of unspoken, personal & cultural stuff. There isn’t a “normal” way for people to sit at a table or to eat dinner, it’s really for the most part people learning from how their families eat, or what’s around them. Often there’s some atmospheric pressure to get to some kind of “normal” eating practice. A lot of my work lies in the politics of that assumption, how we think about normalcy. In eating we make a lot of assumptions that are politically and culturally loaded, and to me I guess that’s what I also consider to be dance.

Is digestion (already) a dance? We have these internal, non-voluntary systems involved with digestion. But the general idea is that food is an internal process, but how can we externalize that which is internal?

IL:

I feel like you really encapsulated your practice well when you were talking about this desire to externalize the process of eating and our relationships with food. How did that factor into some of the specific design decisions that went into creating the space behind Gnaw?

QT:

The first thing that comes to mind [for design] is impulse control, doing the thing that maybe you’re not supposed to do with food. That’s always something that has appealed to me. The visual language in this room is information for the body, it considers the grotesque. We have literal decay here, encased under the glass flooring. And I see it as an invitation to connect food to the body in a different way than eating. You see these decaying foods, and they are these sort of carnal grounds that help us situate our own bodies in a greater cycle of decay.

With the construction of the space itself, the first and foremost thing I wanted to do was put a functional kitchen into an art institution. That was a big goal of mine. And I would like to do that more, because it just sort of changes an installation to have an inbuilt future product. And it changed how the institution functions. We’ve used it so many different times through programming, or even when I’m here I can just whip something up, which I can’t do at most galleries. There’s a lot of other aesthetic decisions that went into it as well. Like one, you know, is referencing the American diner and its fraught history.

We’re also working a lot with gender in this space. I just had a new gender affirmation surgery this week, and this [room] is how I kind of imagined the OR to be lol. I’m kind of nasty like that, like trying to clean up an open wound by putting a bow on it. It’s kind of like how my surgeon cut my bandages into little hearts!

You know, this room is a bit of a punchline about gender. It’s literally leaking and like it can’t be contained. It’s also very much a “girl room,” to me and references my own childhood bedroom. It’s very saccharine: in the glass floor installation, most of the decaying foods are pretty much sugar-based, very sweet-heavy, there’s only really one noodle in there, no protein, no veg. But also, like, you know, a lot of what’s in there are mothers (fermentation starters), so it’s fermenting but also really slowing down the molding process, because this is a nine month piece. I didn’t want it to go so crazy right at the beginning. I really wanted it to develop slowly and have something be in a sugar syrup. You know, it is essentially a preservation technique. But it’s obviously not anaerobic. It’s supposed to do its thing. But yeah, you can definitely make a metaphor out of that and interpret gender to it, you know?

IL:

How do you see the design of the space influencing how people use it?

QT:

I mean, it just functions [as a kitchen]. It’s also made to facilitate performance, so we’ve enforced the diner countertop so that it can be a stage, and of course, people use the space in the traditional sense, where you can sit at a four-top and share a meal. Different performers have played or not played with this format. In terms of how people engage with it, it’s more so about the artists, some of whom that I’ve invited, have already worked in food.

Recently Performance Space had a gala, and Indochine activated it with like this art installation, which was like this big floating disco ball, and I thought that was interesting because I had had no conversation with them, they just took the room and its facilities and activated it in that way.

That just affirmed to me that the room is doing a kind of facilitation, and provides space for people to have a more conceptual approach to food in a general sense. Like it’s prompting people to do that, who aren’t even being asked to do that. We’ve also had performers that aren’t specifically programmed to this space use it, like Young Boys Dancing Group, where they activated the bar. They’re an amorphic group that I’ve been working with that does a lot of like lighting shit on fire and putting things up their ass in a poetic way.

IL:

I last came to this space for a Palestinian community meal hosted by MOLD contributor Amanny Ahmad. Since then you’ve also invited other organizers to use the space. Tell me more about that.

QT:

Yeah, I’ve been really pushing for it to be used in that way. Amanny’s dinner was definitely a highlight in the program for me. In one sense, it was a way to bipass the slowness of an institution signing on to PACBI, and just do what I can with the program, fast. But eating food together in this way was also incredibly intimate, and highlights what drives me politically. But also when you bring organizers together, they organize. Recently I invited my friend Kaija Xiao who runs Gentletime Farms [to use the space], and they connected to their broader collective Choy Commons. They held an event in the space and hosted this amazing drum crew, like an all trans Korean drum squad. But definitely all met up before to talk strategy! In terms of thinking about it from an organizing perspective, the idea is just make the space and connections will be made, real connections, and things will evolve from there.

IL:

I’m interested in this idea of utility and space because our context is specifically in New York City where there’s famously not a lot of it, and it affects how we make and commune together. After staging this exhibit what kind of spaces do you think we need more of for artists, communities and organizers to flourish?

QT:

I won’t speak to that on a broader level. But what feels meaningful to me, and the thing about installing somewhat functional spaces, is that they’re going to be used and have a life of their own. And it’s not that I don’t see value in artworks that are non-usable. Not everything has to be, like, a refrigerator. But for me, I really appreciate my own work that can have these other lives. You don’t have to stop with a particular kind of conceptual function. It’s allowed me to ask, ‘What can happen here?’ And people poke in here and are curious, and you know, we did have a sex party here organized by my partner Bobbi [Menuez]. Yeah, so I wanted a space where organizers could meet people and gain access to resources. I wanted people to have sex here. I wanted people to cook here. You know? And that is the topic of food for me. Because of its somatic factor, its social factor.

IL:

Along the back wall of the space you have a sort of fermentation library, tell me about it.

QT:

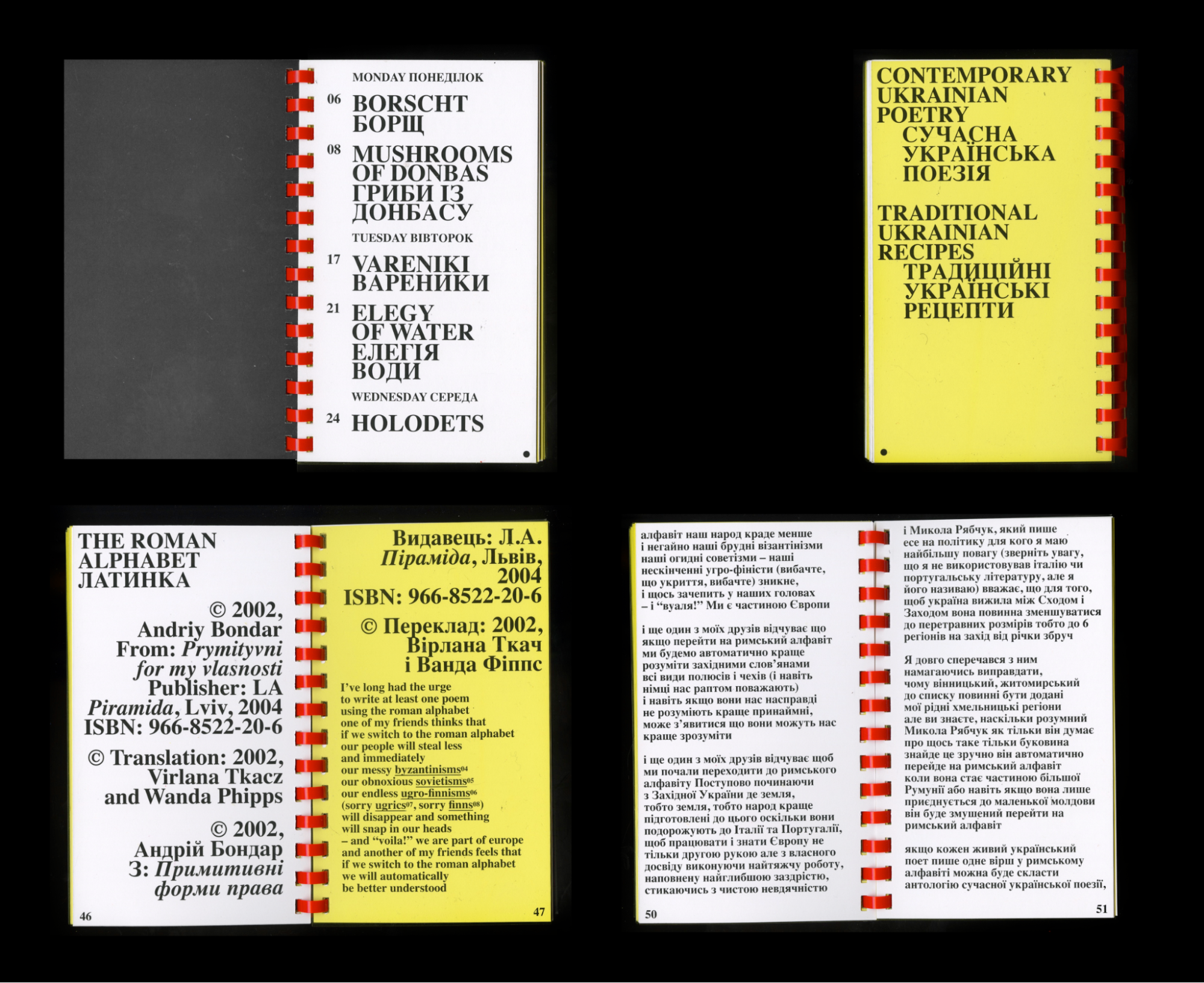

These are community submissions! They’re crowdsourced. With this exhibit we wanted to bring in this leakage of a participatory process, and include our communities’ own stories. Some of them are directly related to gender, because people knew the room had to do with that. So there’s like home-grown T, which is based on the idea that pharmaceutical testosterone is derived from soybeans [by Nico Coppleman]. And then there’s also peoples’ family recipes. So we have this kind of lineage, and people are welcome to submit through the year. Some of them are from my own collection, like that bottle is from the place where I taught in Iceland where one of the organizers of this experimental university had people bring honey from different regions of the world, and they made wine from it. We’ve also got detritus from different performances, like cheese rinds from the exhibit’s opening performance, Tell me when with Bobbi Menuez, Isa Spector, and Samuel Delany . It’s like an archive of the space in some ways too. It’s not really a format of a library in the sense of like, we’re trying to keep these foods delicious, but it’s just to have snapshots of the period. Some of which will be edible at the end and many of which won’t. Of course we’re looking to pull conceptually and literally from it at the end and make a meal out of it.

IL:

I’m sure over time the space has accumulated its own routines. But, what are some of the rituals and routines you rely on in your own artistic practice?

QT:

I’m a longtime meditator, so lots of routine with that. and am on the board for the trans courses in the tradition I practice in. Food has always been a big part my personal rituals. I cook a lot at home for New Yorker. I also have other kinds of service work that I do.

I do think that a big part of me having these kinds of rituals is so that I can make space for letting go and spontaneity. A lot of my work is about creating a structure that can support more of that letting go. It’s like you’re offering constraints for experimentation, and then you get to see what happens. I think that it bodes true for my life, where I have a lot of structure so I can live more wildly. I’m sober and have a lot of these grounding practices, but it means that I can offer a lot more of myself, and be a lot more expansive in how I show up not only as an artist, but as, a friend, and a person existing in this world.