Methods & Provisions is a series documenting the memories, rituals and soundtracks of people who love food.

According to apparel designer turned textiles researcher Rosie Broadhead, probiotics are not just for the gut. Our skin, the largest organ of the human body, plays host to its own ecosystem of bacteria and microbes. After stints working for menswear brands that ranged from Thom Browne to Rapha, Rosie pivoted into scientific research, interested in what it might look like to design on a more granular scale for the skin microbiome. Her research focuses on how biomaterials might help to not only optimize the body, as is the focus in performance wear development, but also heal the body. Currently, under her textile research and development company, Skin Series, Rosie creates sleek, body-hugging basics infused with probiotic technology that help to cultivate healthy bacteria in the skin microbiome, tackling body odor, encouraging cell regeneration, and improving the immune system overall. Recently, I sat down with Rosie ahead of the opening of Superpower Design, an exhibit hosted by Belgium’s CID Grant Hornu Museum currently on view, where she has contributed a series of designed objects that imagine how textiles might be used to hack our hormones. In our conversation we talk about crafting performance wear in communion with nature, the power of fashion as a tool for scientific communication, and the mantras that ground her across her interdisciplinary practice.

Isabel Ling:

As a textile scientist and designer your work lies in studying the interface between skin and material. How did you arrive at this practice?

Rosie Broadhead:

So, my background is in fashion and design. I was a menswear designer and I worked in the sportswear industry, really focusing on functional performance-based garments. It was very much following this idea that form follows function and obsessing over the material. Questions like, ‘Where can you place seams on clothing to make an athlete more aerodynamic? or ‘What colours make you visible in low-level lighting?’. Really focusing on the functionality side of clothing. I think that’s often what menswear or workwear was about originally, and that’s how I started my practice as a designer.

Since working in sportswear or performance wear and knowing that your clothing can influence your body, I became especially interested in clothing where the textile is directly in contact with your skin. I became conscious of how your clothes can affect your body. Asking, ‘Aren’t our bodies enough?’. And exploring, ‘What is already existing on our bodies that is functional?’ Do we really need these extra layers of performance to make us feel cool, or not smell or whatever it might be. In addition to that, I was also noticing at the same time that a lot of these textile finishes were often synthetic or using chemicals. I wanted to see, or look at nature to find performance. That’s what really drew me to looking at the body and the skin, and the skin and textile microbiomes— and how you can manipulate these two kinds of different surface ecologies.

I really started to focus on understanding what the skin microbiome is, and why it is so important to the health of our body. I then began a collaboration with a microbiologist, Dr Chris Callewaert, who I’m actually still working with now, after five years. He’s a Belgian skin microbiologist. This is why I’m now living in Belgium, actually. I moved from London to Belgium, for this collaboration, and I started working at Ghent University to start understanding more about the relationship between this skin and textiles, and this microbiome between the two. But maybe I haven’t really explained what the microbiome is..

IL:

Yeah, what is the skin microbiome? And how does your research engage with it?

RB:

The skin is quite similar to the gut, which means its surface is covered with bacteria, fungi, viruses — these living organisms on the skin are fundamental to its health. We often think of ourselves as individuals, but actually, more than 50% of our own cells are actually non-human. We’re living in this synergy with other microorganisms, which I really love as an approach to consider identity. Normally these bacteria on our skin are working for our benefit, so as long as this ecology of bacteria on our body is in balance, then it’s beneficial to the skin, health and immune system.

Often, in more urban or Western environments, we’ve undermined this microbial ecosystem through what we’re putting on our skin, what we’re eating, or cleaning products we are using. The understanding that bacteria is bad has meant that there has been a higher increase in certain immune system disorders, like asthma or psoriasis. Things that have meant a compromised ecosystem, and it sometimes can be traced back to the fact that the skin, my skin, or gut microbiome has been compromised. Which is why I focus on stating the importance of the skin microbiome, healthy bacteria, and trying to encourage probiotics on the skin through clothing.

IL:

I think these days knowledge around maintaining a healthy gut biome through things like fermented foods and probiotics is pretty widespread, but how is maintaining a skin biome different from maintaining your gut biome?

RB:

It’s actually easier to discuss in terms of what bacteria we don’t want on our skin. There’s been a lot of studies recently on Staphylococcus Aureus, for example, or Corynebacteria, bacteria that have been associated with psoriasis, eczema, body odor — culprits for these kinds of skin immune system disorders. So it’s about increasing neutral or healthy bacteria on the skin to try and counteract these unhealthy bacteria like the ones I mentioned. It’s the same way that you would take probiotics for the gut, where you’re trying to increase healthy bacteria, like Baccili, Lactobacillus. It’s the same route, same methodology.

I wanted to see, or look at nature to find performance

IL:

So how are you infusing your clothes with this bacteria?

RB:

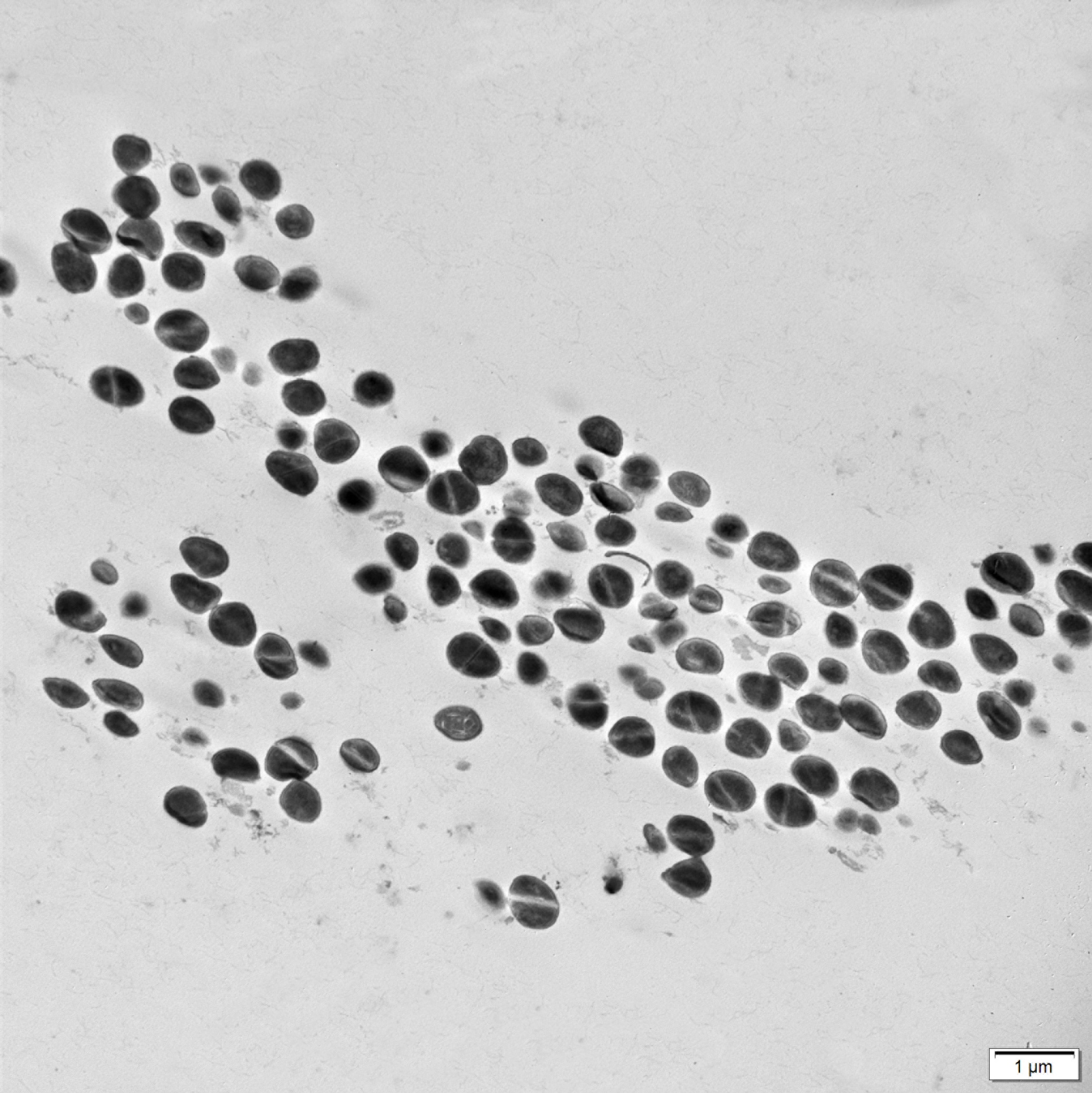

I developed this technique at Ghent University in the microbial department. It’s quite challenging to include healthy bacteria into clothing because often the ones that are considered healthier are a bit more sensitive to heat and water. It became a technical challenge to try and include this bacteria in textiles. I had to create a very tiny shell around the bacteria to hold them and keep them dry and protected. The idea is that when you rub your clothes, these little microcapsules break open and release the bacteria onto your textiles. And as long as it’s in contact with your body then it can grow and influence your skin microbiome.

I focus on therapeutic textiles and that includes healthy ingredients and their benefits to the skin. So it’s not only just bacteria, but I’m also interested in the healthy properties of algae, for example. In the same way that you think about skincare or your nighttime routine is similar way [to think] about textiles like how can we include something that is healthy for the body and provides these natural health benefits?

IL:

Well, I was curious about the choice to use algae. I know different types of materials also hold different types of healing properties, as well as plant-based dyes like indigo, too. So I’m curious how you landed on algae, and what sort of healing properties are specific to that material?

RB:

Yeah, I mean, I think even organic cotton is quite underrated because often that’s what I would recommend someone to wear if they have psoriasis or eczema or something bio-based, because it’s very breathable, natural and it’s unlikely to cause any irritation. The same with wool. It is interesting because wool has natural antibacterial qualities as well. So often, you can wear it for like a whole week and you don’t need to wash it… I don’t ever really wash my wool, really.

IL:

I don’t either, so I’m glad it’s scientifically backed.

RB:

Yeah, it also ruins the fabric if you wash it. Sometimes I like to spray it with this probiotic deodorant one of the collaborators in the lab is working on instead of washing it. Dyes are also really interesting. Indigo is a beautiful way of developing color because it’s also a process of fermentation, where it is green initially and then through the oxidation process it turns blue. It also has antibacterial qualities to it and it has a history in Japanese workwear as being something that you could wear next to your skin, with these healing properties that prevent any unwanted bacteria. Logwood, too, which has this very beautiful deep purple color is known for its anti-inflammatory properties for the skin as well as wound healing.

Algae is interesting because it has an antioxidant property for the skin and can encourage cell renewal and it’s also rich in vitamins and minerals. It encompasses a lot of natural health benefits, essentially in this one ingredient. So that’s why I like it.

IL:

Where do you source your algae yarns from?

RB:

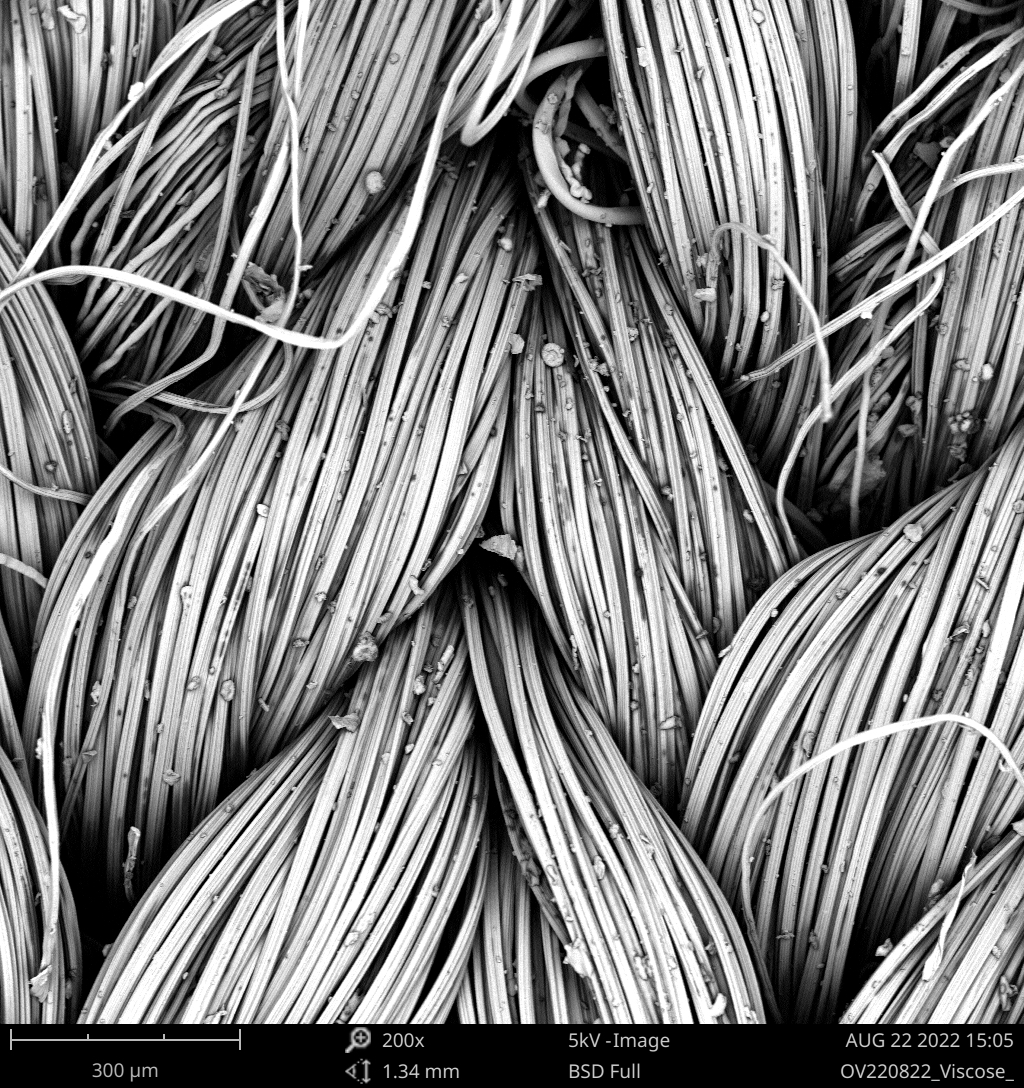

The algae is sourced from Iceland, but the fiber is made in Germany. It’s a cellulose process. The algae is added to a yarn at the wet spinning stage, where it gets embedded into a fiber, and then these fibers are twisted into a yarn. There’s been testing on it that proves that you can still get the benefits of this ingredient even when it’s inside the yarn. It’s a slightly different technique from what I do with the probiotics, which is a microencapsulated treatment on top of the fabric, which takes place at the end of the textile development process, between finishing the fabric and making the clothes.

IL:

I’m curious, you said that the probiotics are released through touch. As someone who is always playing with my clothes, I want to know if it’s a one-time release or a sustained release?

RB:

We want to make the Probiotic Treatment in a way so that it’s as durable as possible. When it comes to the treatment the bacteria are enclosed inside, many bio-based microcapsules on the fabric surface, so it’s a durable process that can last between 30 and 50 washes.

IL:

I’ve seen a lot of news come out about how the textiles that are used by fast fashion brands are correlated with cases of eczema and psoriasis. I’m interested in how you contextualize the clothes that you’re making within a wider fashion industry with its attitudes toward consumption and manufacturing?

RB:

One of the main things I explore from a sustainability perspective is the supply chain issue from the material manufacturing and construction stage. From growing the crops of cotton, for example, to dyeing and finishing the fabric, there’s chemicals at nearly every stage of the production process. The solution I’m providing looks to nature for performance attributes, to try and replace these toxic processes. Aside from the capsule collections that I develop, and the editorials that I produce, I’ve positioned myself as a material supplier rather than a brand that is putting out a seasonal output. Because I don’t want to fall into that category that I have to create multiple colorways or winter, spring, and summer collections. It’s more about creating a new supply chain by providing materials that I want other brands or designers to be able to make use of so they collectively can make a bigger impact.

IL:

You’ve had such a long history of working in menswear fashion and design, how has that sort of experience of making might translate to your current processes of making? What are the differences and similarities between the disciplines?

RB:

It was actually a really big jump for me to go from working in the fashion industry to working in research. As a designer you’re constantly thinking about what’s next on this seasonal production roller coaster, but then, in academia, or research, the focus, or value, is really put on testing, experiment design as well as on the data. The scale is also completely different. From a design fashion perspective, the question is often, ‘What is the image?’, and about how it looks. But here, when I was researching these material developments, the scale that we’re working on is a one by one centimeter swatch of textile. The outcome is reports and Excel formulas, and graphs, which was completely new for me. It’s a completely opposite way from communicating from a design perspective.

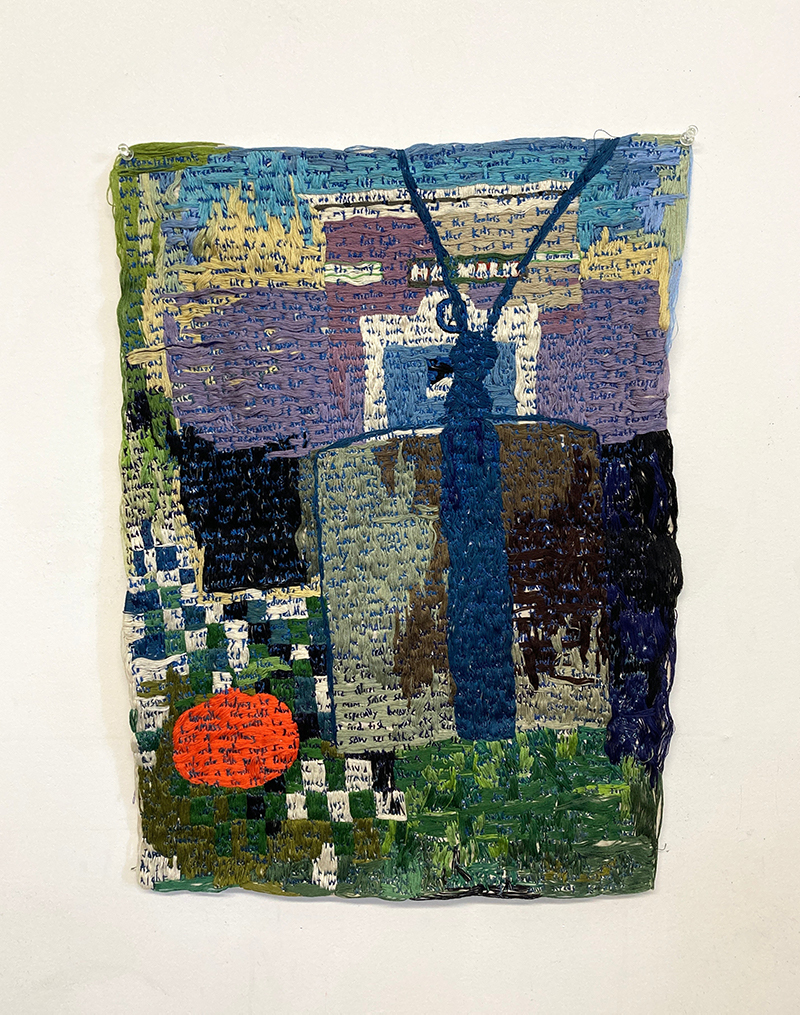

I think that was why it was so important for me to make this research tangible, and tell a story through the material. For example, what does bacteria look like? Can I visualize that on the textiles? Or how did the pieces make you feel? What should these garments look like to emphasize their benefits to the body? So I think it became a communication challenge, conveying this research in a fashion context, because I feel like that’s what makes people excited at the end of the day.

IL:

You’ve recently released a new collection. How has your research evolved? What are working on now?

RB:

I’ve been working on a research project about hormonal changes and female health. It’s about how physical and mental health are really connected to hormone health, and the natural ways that you can hack your hormones using, in this case, your clothing. As you get older, as a woman, the symptoms of menopause are really associated with lower estrogen levels. It can’t be completely boiled down to just that point, it’s more complex than that, but a lot of symptoms are linked to this. Your estrogen starts to deplete and then often you have some side effects like osteoporosis, and bone mineral density can be affected. Then, you have disruptions in your vaginal microbiome, so you might be more susceptible to infection, for example. Cortisol levels are quite linked to your reproductive hormones as well. So a part of the ideas was how your stress or cortisol levels and thus increase your estrogen levels.

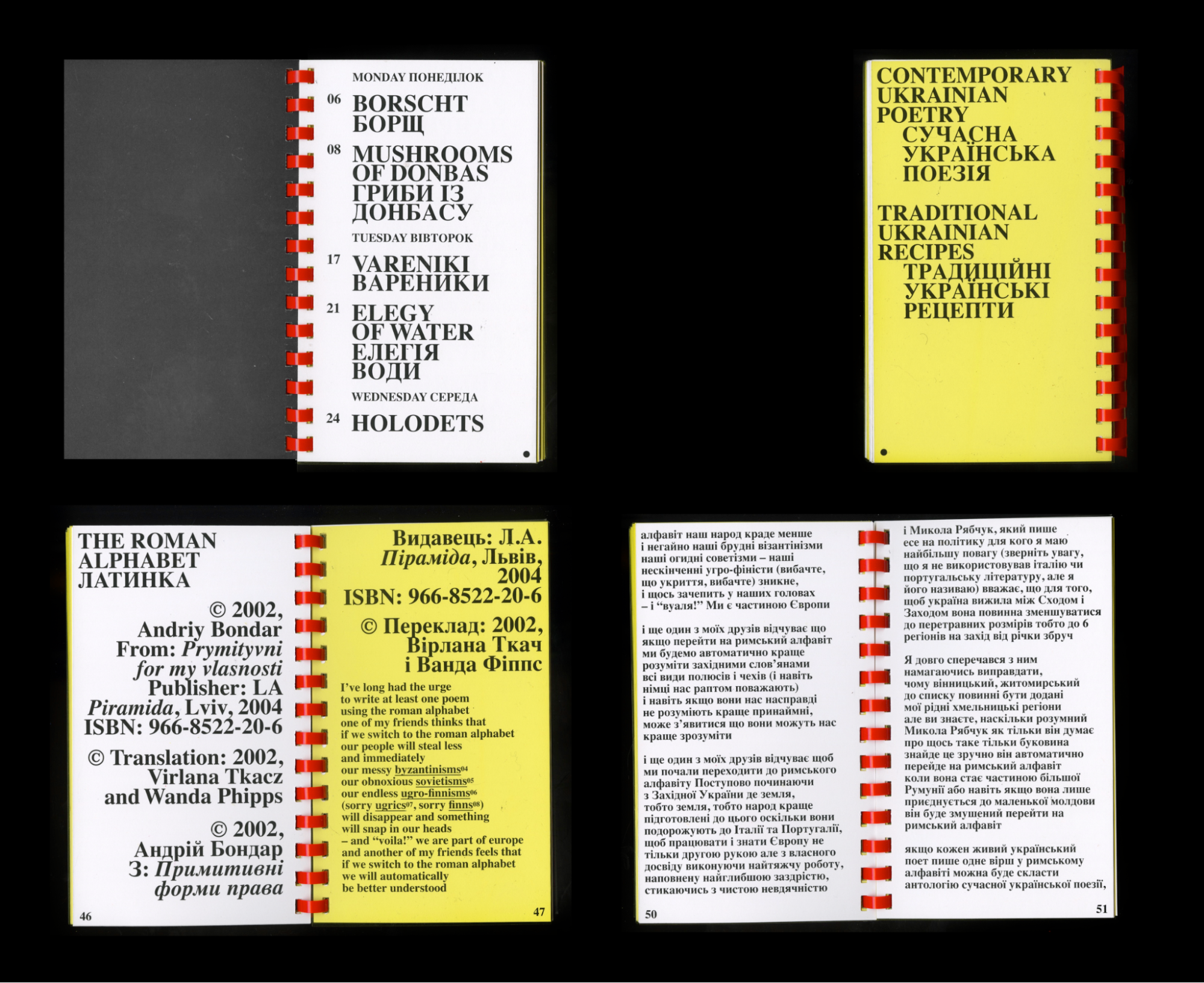

The research is now part of ‘Superpower Design’ exhibition at CID Grant Hornu Museum, Belgium. These pieces are not commercially available, necessarily, but it’s more of a think piece about how we can discuss hormones and their relationship to what we’re wearing. Some of the pieces I included were prebiotic underwear. Not probiotic, but prebiotic, which is food for the bacteria. When we get older as women the sugars or the nutrients for the bacteria can deplete, which means that there’s less lactobacillus, which is a bacteria that is associated with health. So I wanted to think about how we can create underwear that has not just bacteria, but also food for the bacteria.

There’s also been some research on certain frequency levels or vibrations, and how they can help to stimulate hormonal health and increase estrogen. So I designed a vibrating neck cushion that you might travel with, which vibrates at 30Hz. Then there’s magnesium sulfate, which can really affect your cortisol levels and regulate your mood. And magnesium is actually transdermal, like you can bathe in it, like the salt baths, for example. So why not nourish your body with a magnesium t-shirt?

IL:

As someone whose practice spans several disciplines— from research, to a garment, to a final project displayed in a museum—what routines and rituals do you carry across the different types of making you have to engage with?

RB:

In terms of routine, the approach can be very different for all of them. But in daily life I eat the same breakfast every day, because I really don’t have so much routine and so my focus lies in the small things. I eat oats with plant-based milk and banana. It’s really simple, but there’s a lot of energy in it. I feel like it’s really grounding to just be like, this is how I’m going to start my day.

IL:

Right, speaking of cortisol levels, eating breakfast can really help you regulate cortisol levels, especially if you drink coffee.

RB:

Having breakfast gives you a moment to take your supplements. And there is something else that I’m trying to incorporate into my daily routine as well, because it’s better to do it on a full stomach. It’s kind of difficult in an urban environment to really focus on health, because we’re interacting with elements you can’t really control. Like the air the we breath, noise pollution, water quality.

IL:

Beyond breakfast, what are some of the routines that help you provide the structure to your day that you mentioned before?

RB:

My mom is quite influential for a lot of my health and body-related questions, I suppose. And when I was younger I used to go to the homeopath for example instead of the doctor for physical and any issue, emotional issues, everything. She’s also been a practicing Nichiren Buddhist for the last 10 years. I’ve taken a few notes from her routine. Like, when things seem a bit chaotic there’s this mantra that she always says and I try and think about that in the morning and, and the evening. It’s a small contribution that can keep me grounded.

IL:

What’s the mantra?

RB:

“Nam myoho renge kyo”, which is about devotion. That kind of grounds me because I’m trying to tackle so many different fields and research structures. There’s quite some chaos to it, but that’s a good way for me to find a tether of routine.