Methods & Provisions is a series documenting the memories, rituals and soundtracks of people who love food.

Orysia Zabeida is a designer, artist, and educator currently based in New Haven. Her work explores the intersections of identity, food and the social dynamics of dining through graphic representation. A graduate from the Yale School of Art, she also studied design at Université du Québec à Montréal and Haute école des arts du Rhin–Mulhouse in Strasbourg, France. We catch up with Orysia to learn how her rituals and routines triangulate her practice.

Isabel Ling

Tell us a little bit about yourself and your practice.

Orysia Zabeida

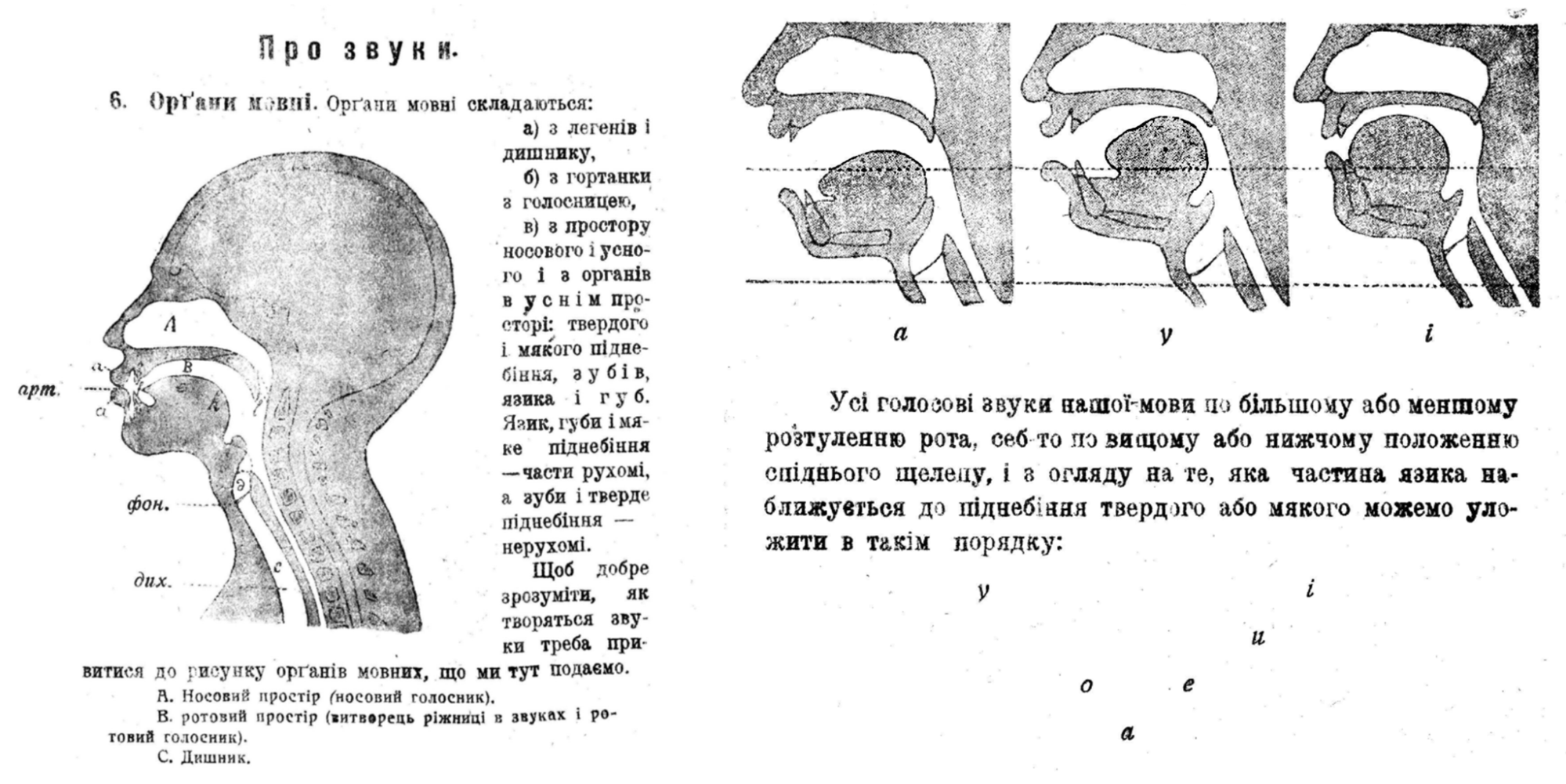

The meaning of my name–Orysia, stems from the Ukrainian word Oрати which comes from ancient agricultural jargon and means to plow the field. I find this fact quite amusing since my work has a lot to do with digging, mapping, and research–it’s very close to preparing land for seeds. I work with ideas. My practice involves visual didactics and illustration and explores images in teaching and learning processes. In my practice, design thinking is a process I’ve been using a lot. We are naturally inclined to think convergently and look at problems through a microscope. Design thinking encourages you to think divergently. It enables you to look at things through a telescope, see the big picture, and see how things work and connect from a holistic perspective.

IL

A lot of your work has to do with mapping and visualizing food graphically. Can you speak more on how the act of categorization factors into your practice?

OZ

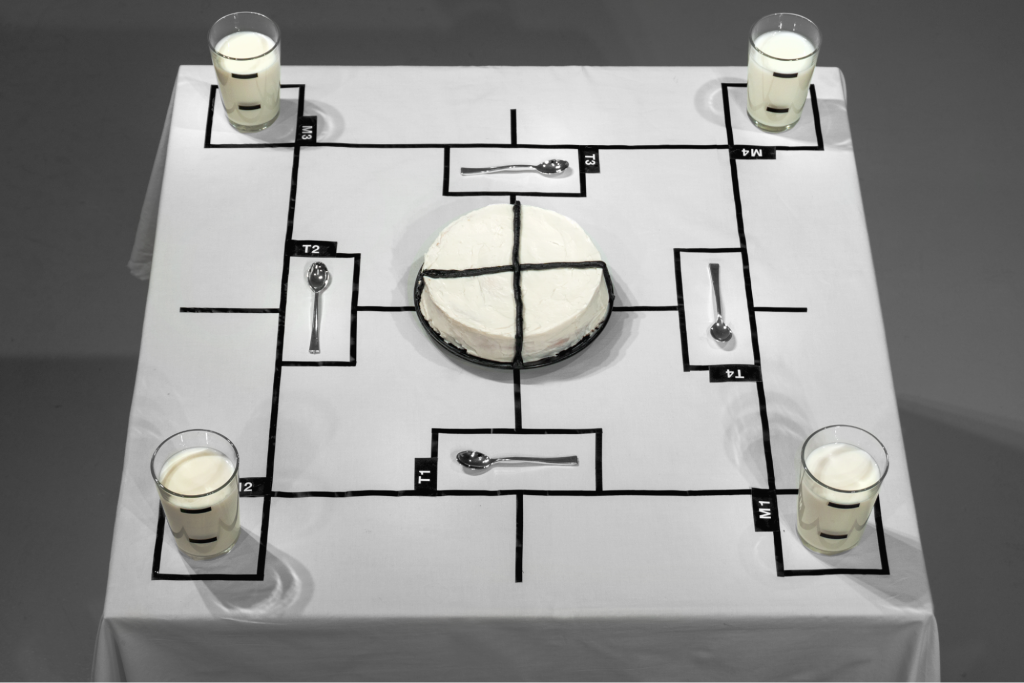

I’m interested in languages and translations–how abstraction can be defined and vice versa, how something very concrete can exist in a more poetic and abstract form. I’m fascinated by those kinds of shifting borders and definition overlaps. Categorizing helps me define parameters. I love imagining my project and framing my research with schematic drawings and words. It helps me visualize the construction of my piece. I have been doing a lot of participative design work, and the process involves creating parameters. Those have to be simultaneously rigid to guide the participants but also quite flexible to allow people to explore and create something unexpected within that imagined space. For example, I recently designed a generator that helps slow eaters and avid talkers get an equal chance at a cake by moderating the dessert eating experience with random behavioral instructions. I often invent or misuse tools to orchestrate scenarios and create spaces that allow diverse audiences to collide in unexpected ways. Similarly, I use that kind of approach even for projects that are not intended for explicit interactive participation. I give myself and others rules and space to play.

IL

Works like Mother Tongue seek to create a bridge within your lived experience. Could you speak more on how your work with food deals with heritage?

OZ

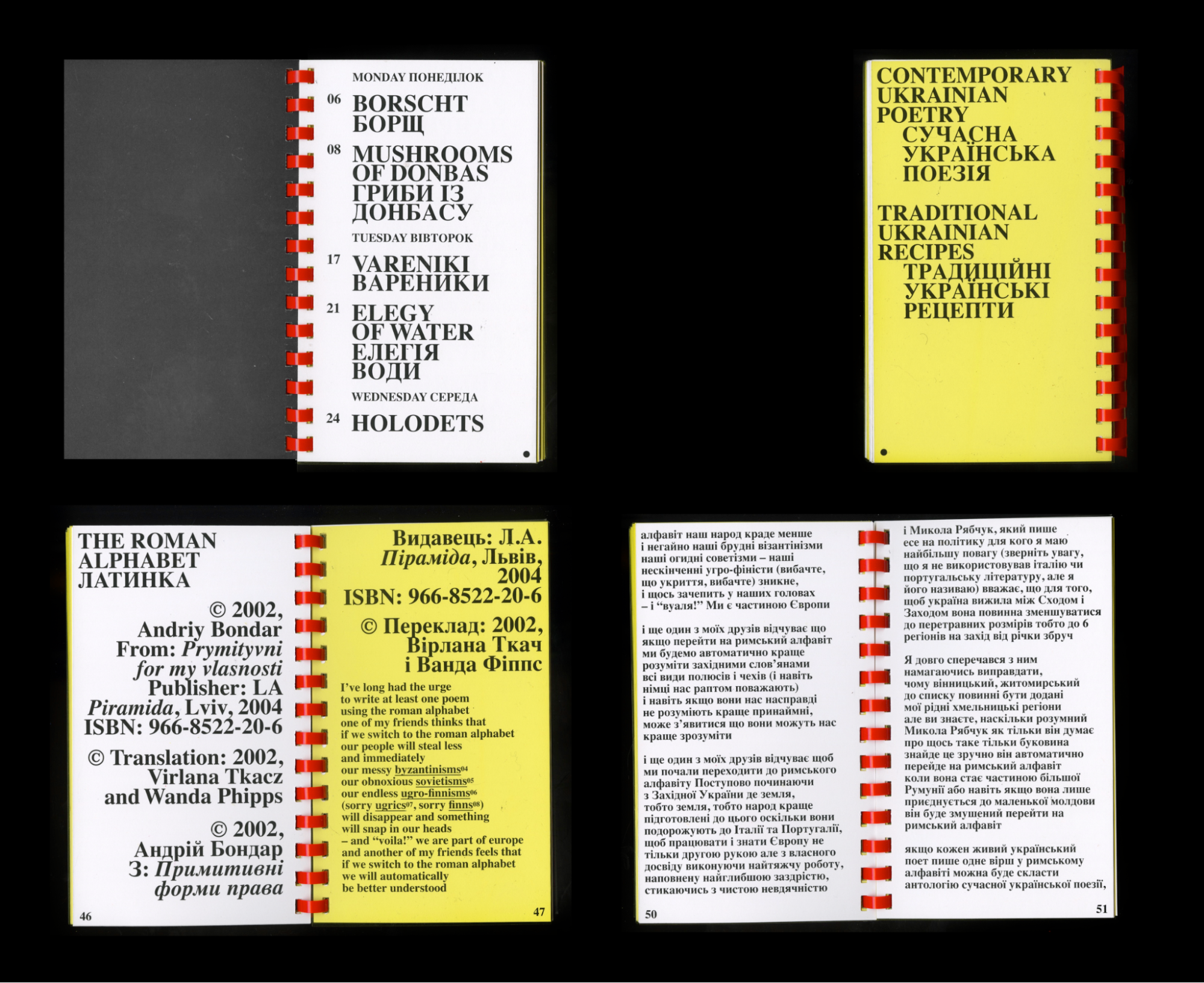

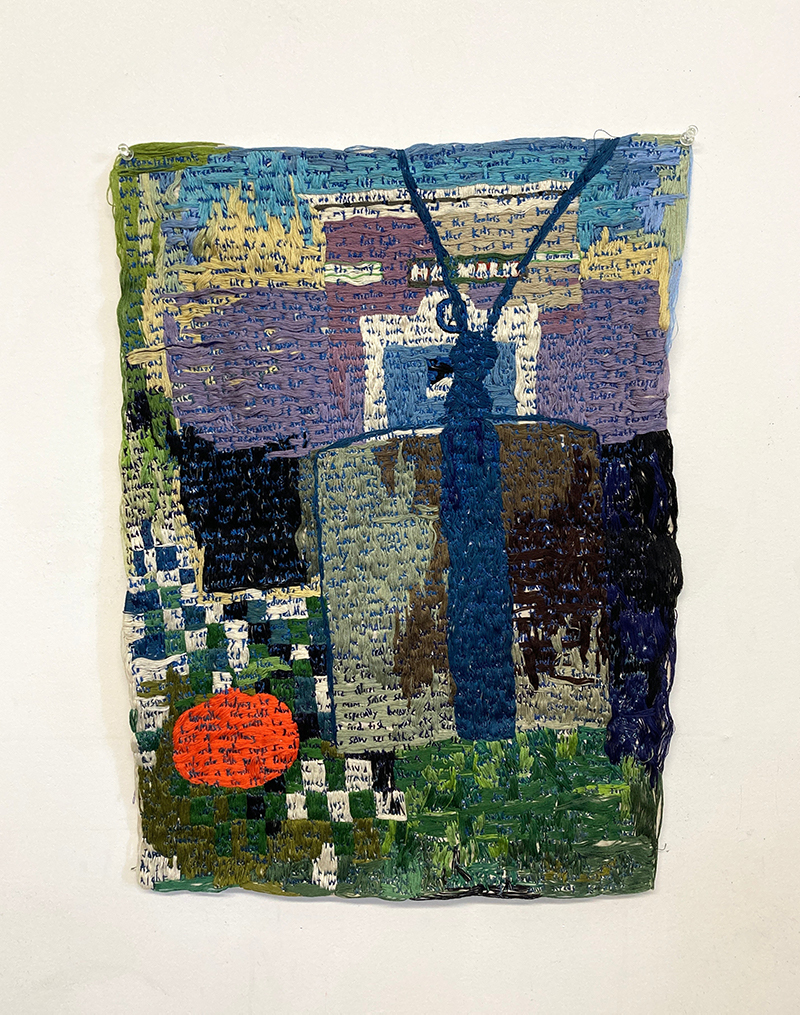

Mother Tongue was conceived while I was returning from Ukraine before starting my master’s. I felt powerless and shaken by the ongoing war and the international inaction towards Russian aggression. In response, I created this anthology combining seven traditional Ukrainian recipes and seven contemporary Ukrainian poems. It’s a sort of silent resistance piece celebrating the people I love. The table of contents matches one recipe and one poem for each day of the week. By mixing traditional recipes and contemporary poems, I wanted to bridge the past with the present and make something that would help me imagine a positive future. A language, just like a recipe, is passed down from generation to generation and is a way to preserve culture. Ukrainians, over centuries of Russian assimilation and occupation, have slowly lost their identity. Our language lives in dispersed pockets of immigrants that fled political instability and corruption. Even though my parents moved to Canada after Ukraine’s independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, most of my family still live in that reality.

IL

What is your earliest food and music memory?

OZ

My earliest food memory is the smell of my mom’s sour cabbage soup. My dad would also help with cooking and present his original dishes in combinations of impressive sculptural assemblages. For example, he would make a sun by aligning pickles and raw garlic around an impeccably smooth mashed potato ball or place walnuts in line with a raisin in between each nut—that would be dessert. He never followed any recipe and wasn’t scared of unusual combinations. Nowadays I catch myself doing the same.

Last time I traveled to Lviv just before the pandemic, I recorded an impromptu gathering of singers in front of the Opera. They remind me of my early music memories. I was part of a Ukrainian orthodox church choir my whole childhood in Montreal. We lived next to a Haitian Baptist church. Every Sunday afternoon, after coming back from the service, I would hear joyful singing in Creole through our back alley. I remember asking my mom why they got to sing happy songs. I’d say that that mix of liturgical singing styles is the soundtrack of my youth.

IL

How did food become the preferred medium for your practice?

OZ

It’s something that happened gradually. My work is inspired by daily life. Food is a constant I’ve never intentionally explored and realized recently that it bridges a lot of my interests like preservation and memory, identity, language, and translation. Unlike anything else in life, everyone has a relationship with food; it is cross-cultural, beyond language, and a highly manipulative form of communication. The way we interact with food is very telling of our state of mind, our social status, political views, and our personality. It’s the intimate yet collective and performative aspect of food and its preparation that I am interested in–how a recipe and its content can tell a story without words but still through our mouths.

IL

What do you listen to when you are working? Is it different from what you listen to when you’re cooking for pleasure?

I love silence when I’m working. I love hearing my thoughts and tools. If you pay attention, there’s no such thing as silence. I love hearing the music of the knife chopping, the crescendo of onions sizzling in a pan, the birds and pigeons chatting next to the window–that’s bliss.

In Tchervonograd, my grandmother has a radio in the kitchen she never turns off. It was made in Soviet times, and it’s so old that the antenna can only clearly pick up one channel. I’m impressed it still works–things were made to last back then. When I spend the summer with her in the kitchen, I love discovering local music. I’m always very attentive to lyrics. If a song has a good melody but bad lyrics, it’s an automatic turn-off for me. I remember hearing this tune where the musician was singing about time and old photographs and that the only valuable thing in life is friendship and shared laughter around the table. The singer urged the listeners to express their feelings and pick up the phone to invite friends for dinner one by one.

IL

Do you have a routine or ritual you regularly use in your practice?

OZ

I take a lot of photographs. One of my favorite rituals is to actively observe. I seek and document patterns encountered in everyday surroundings. Pairs of strangers wearing similar outfits, things, or words that align through a specific perspective and how they look on different days with different light. I also try to intentionally provoke moments of awe. Like I would wake up before dawn to cycle up a local mountain and watch the sunrise.

IL

What is your favorite meal to share?

OZ

That’s a difficult question. I can’t decide between borsch and vareniki, but I think I’d have to say potato vareniki–that’s my go-to hosting meal. Vareniki translates to “boiled things.” They’re perfect for sharing.

Preparation takes time. I make the dough the night before, and the ball has to sit in the fridge overnight. The next day, I cover the table with flour, and I roll the ball into a thin sheet and sprinkle it with flour again. My favorite part is cutting out the shapes before filling them with potatoes. Like my grandma taught my mom, my mother taught me to use the rim of a glass to make perfect little circles. Then I use my fingers to scoop the mashed potato and enclose it in the circle dough sheet. It’s a very meditative process. Finally, I grill the dough after boiling the vareniki. So it turns golden and crispy on the outside and remains soft on the inside. I usually serve them with fresh shallots and sour cream. The contrast in texture and temperature is super important. The vareniki must be hot, and the sour cream must be served super cold.

The presentation also counts. I’m susceptible to how things look and the kind of plate I use. I learned that eating from a heavier bowl can make you feel like food is more filling and tastes better than eating from a lighter receptacle. In design terms, this instinctive relationship that guides and influences interactions between objects and people is called affordance. I’d love to make my own ceramic bowls one day, but I’ll share my vareniki in what I have until then. As long as they are made with love, care and attention, it always tastes good.

Listen to Orysia’s full playlist below.