The Visuality of Mutuality is a column about the ways graphic design can help support local restaurants, establish deeper roots for food sovereignty, and nourish local food ecologies.

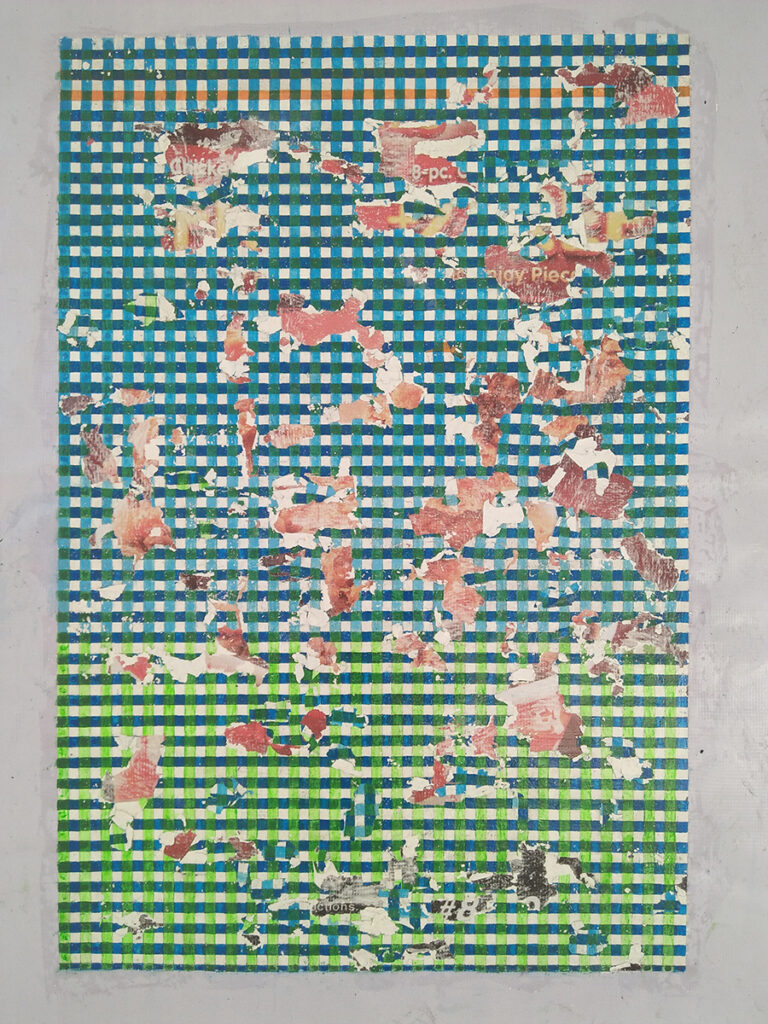

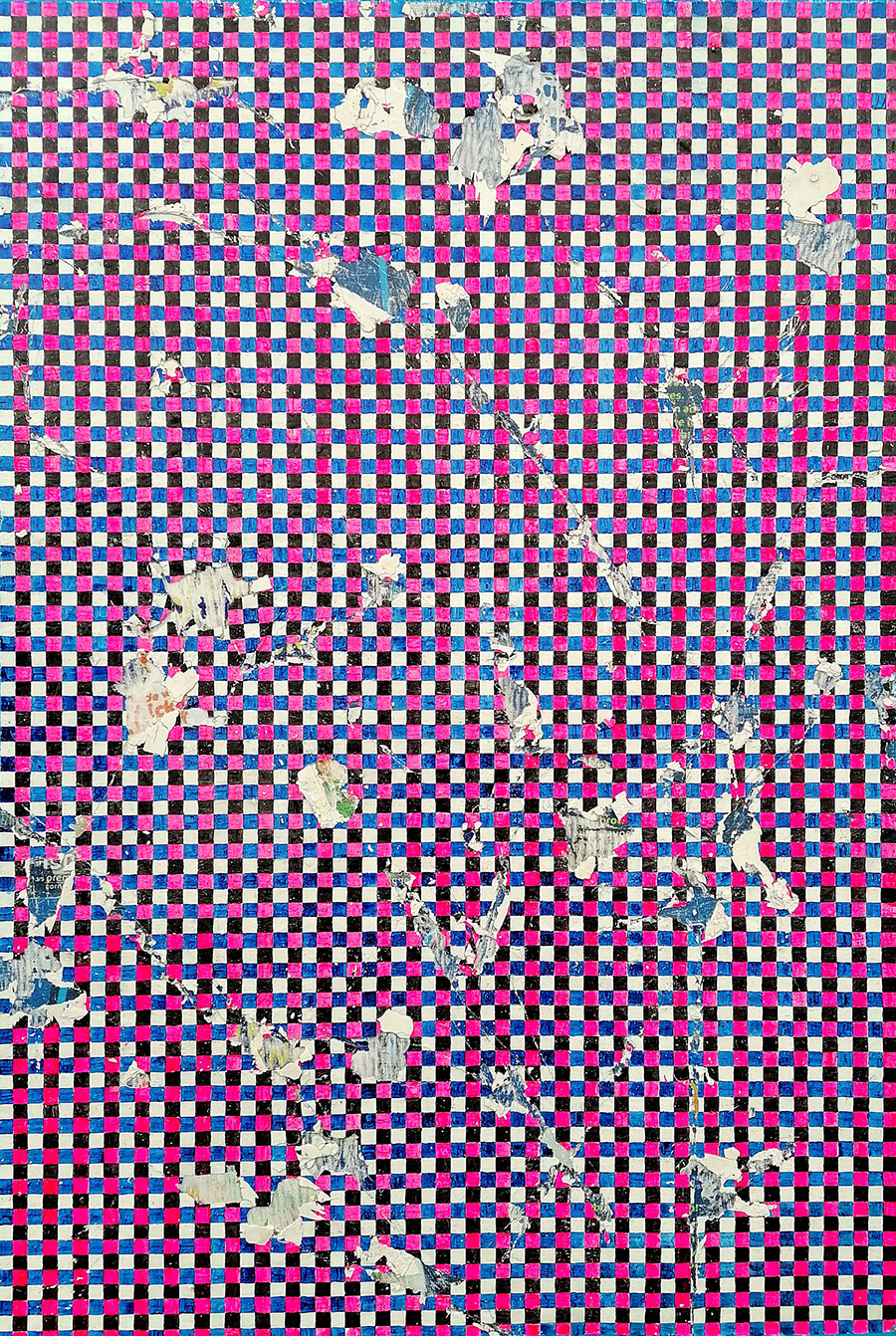

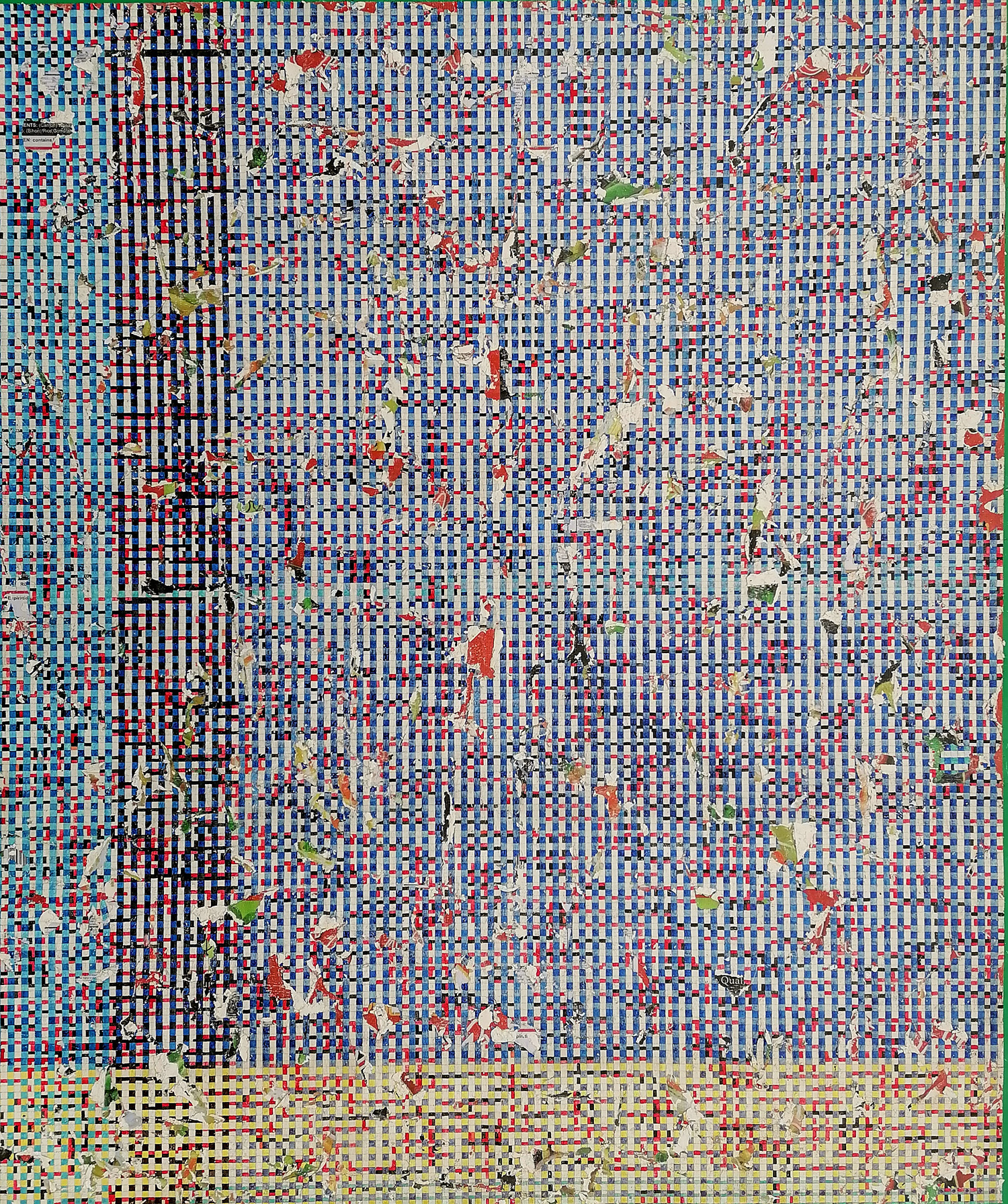

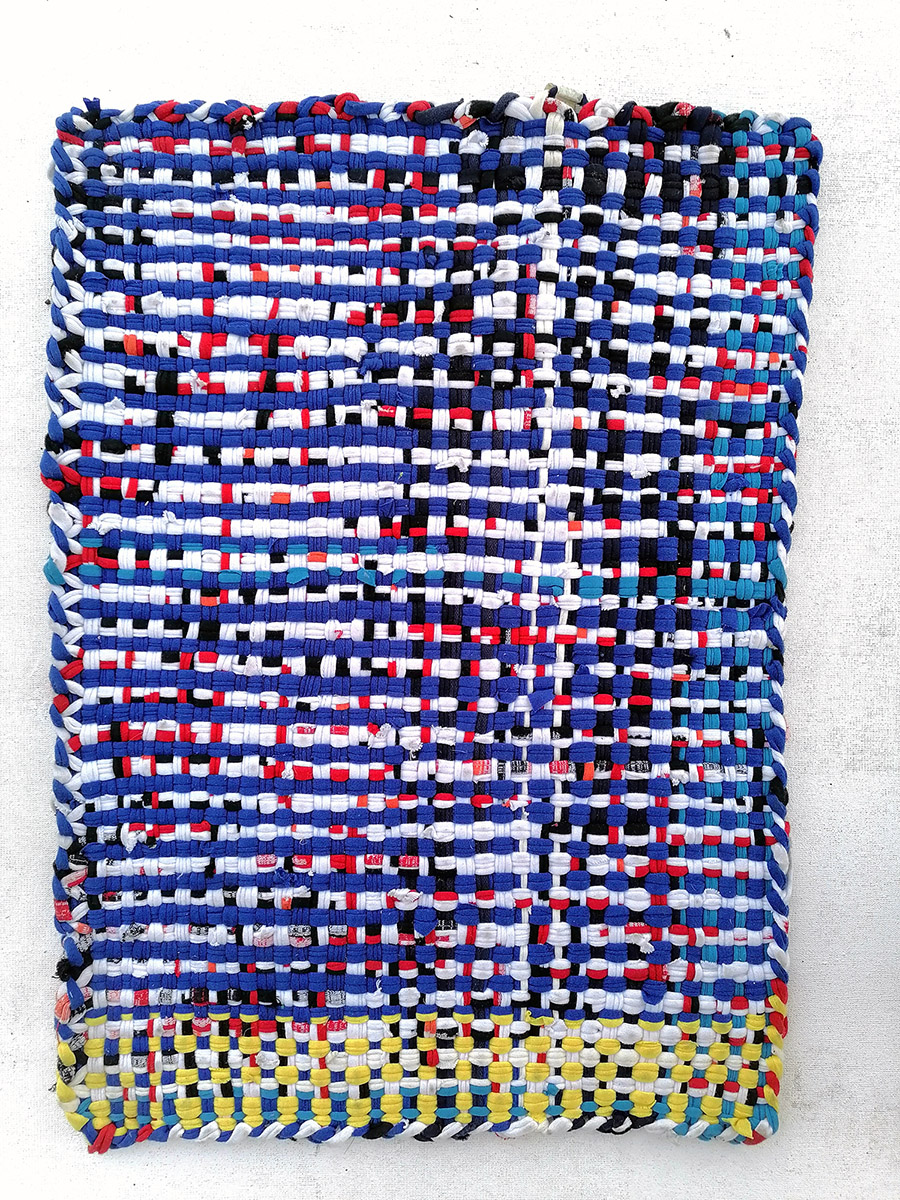

Every material used in Kristoffer Ardeña’s Ghost Painting series is gleaned from the artist’s immediate surroundings. For canvases, he uses tarpaulins, commonly seen in the Philippines, where he lives, as the surfaces for advertisements or announcements. The paintings’ gridlike pattern and bright colors mimic the basahan retaso rugs found in many Filipino households. He buys the thick elastomeric paints from a local hardware store, where they are always in stock, since it’s the best type of exterior paint for withstanding tropical humidity.

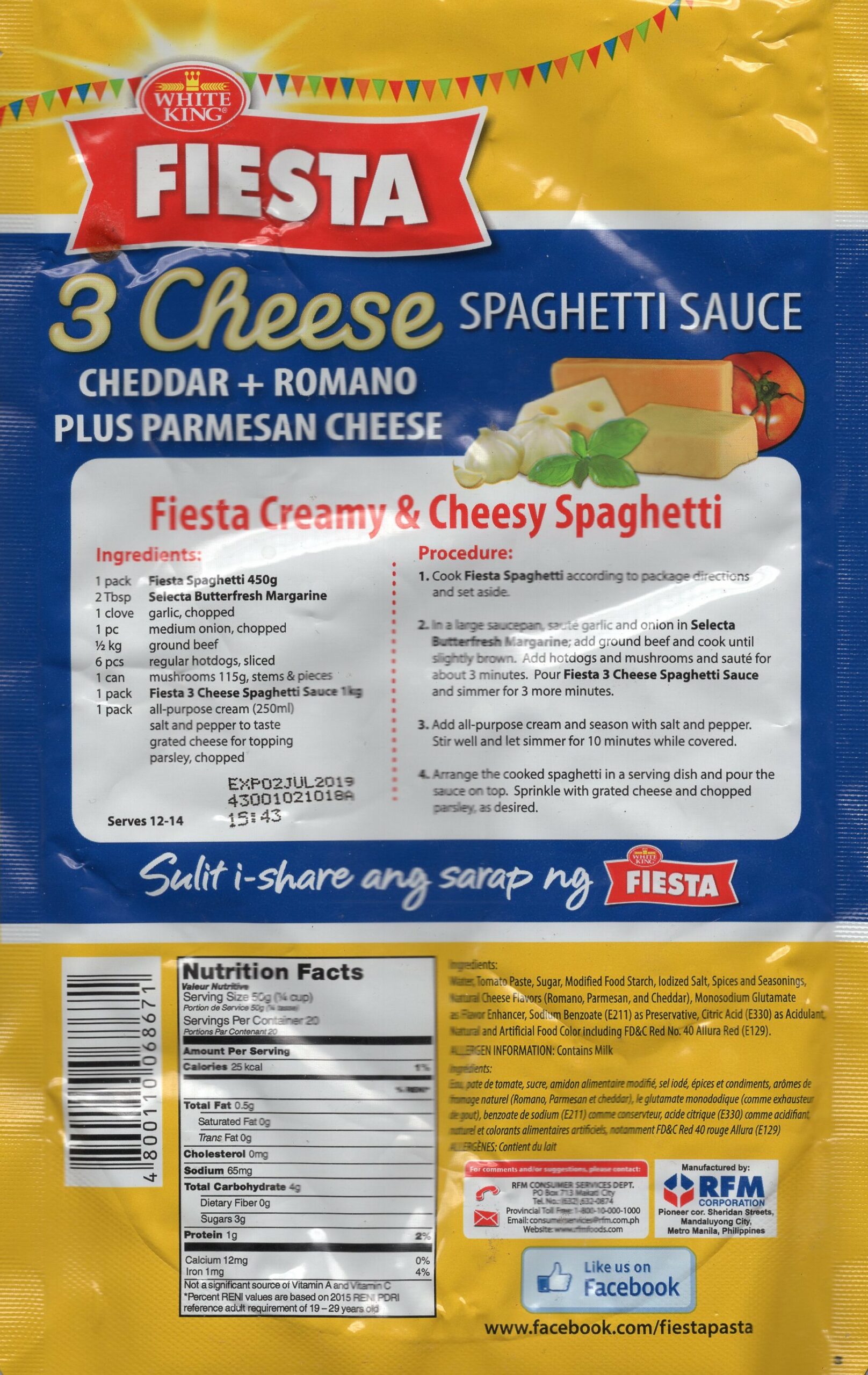

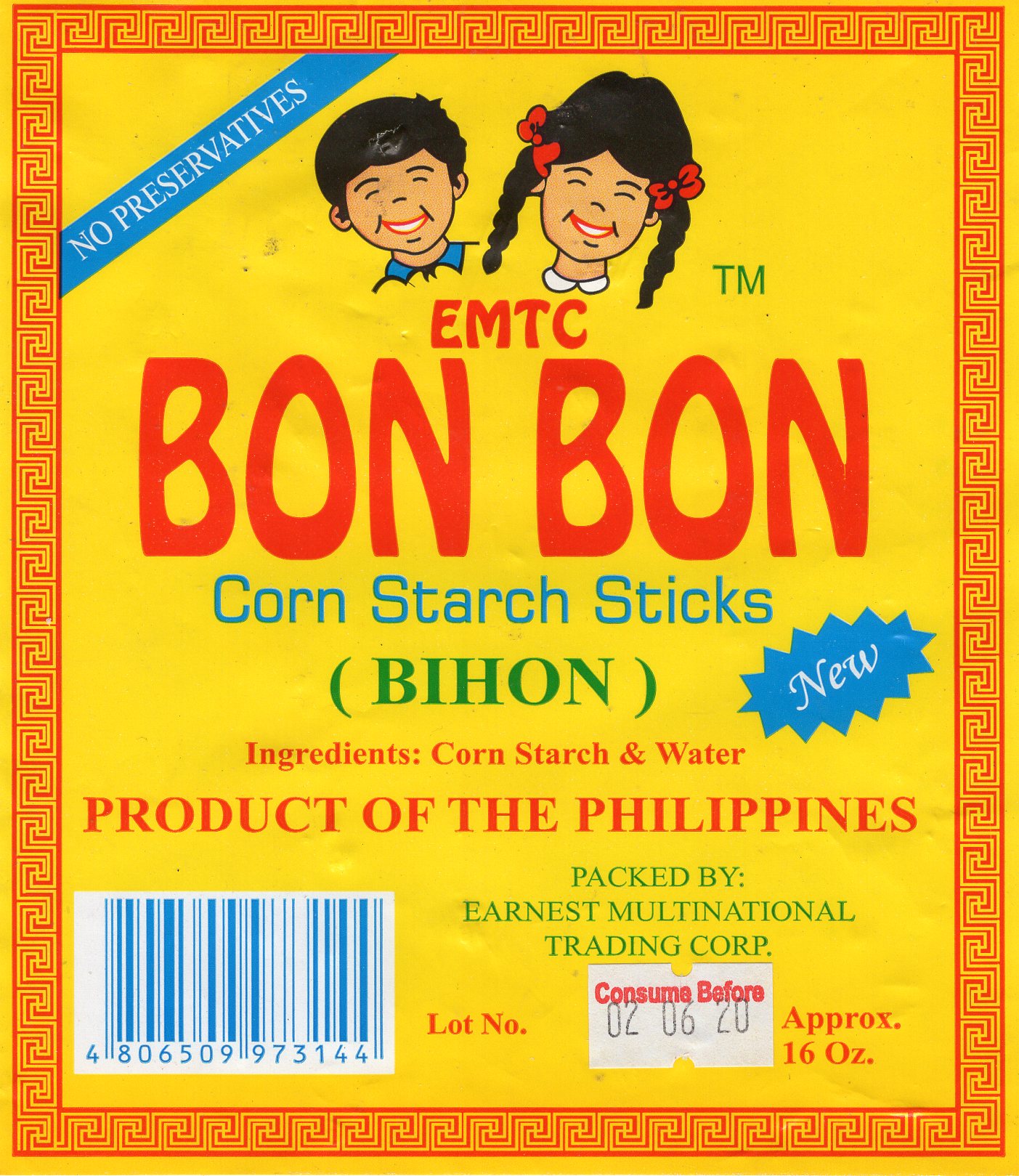

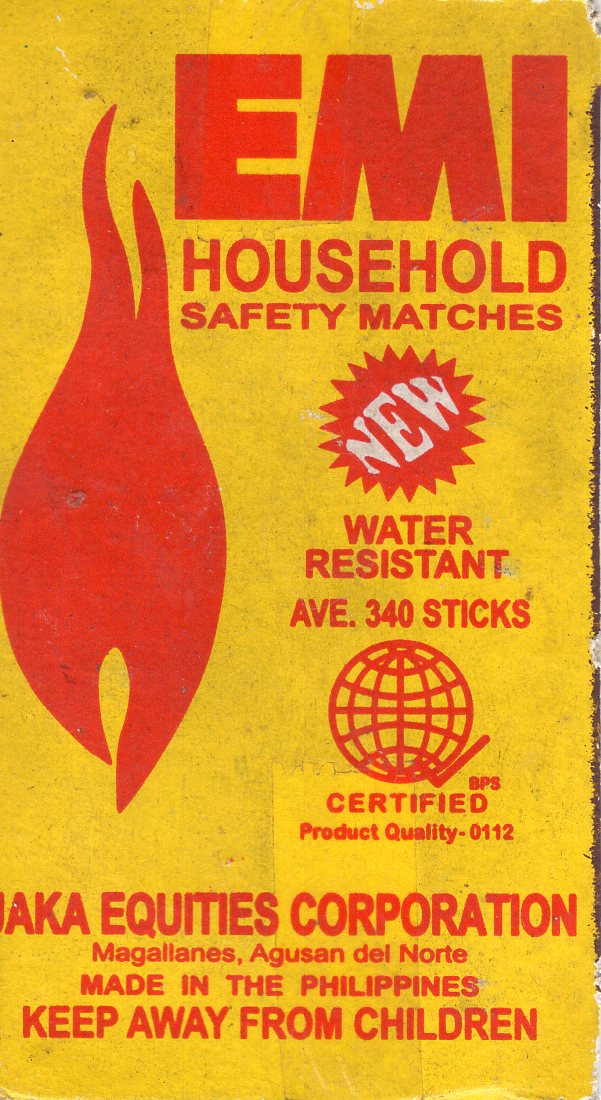

Then there are the pieces of packaging that form the basis of the paintings, just peeking through the cracked and distressed paint, and revealing the food and products that punctuate Ardeña’s everyday life. Ardeña collects the labels of commonly used brands—555 Sardines, Chippy corn chips, Fiesta Three Cheese Spaghetti, Bon Bon bihon—scans them, enlarges them, and prints them onto the tarps, before painting on top of them. “Material, even material you can find in different places, becomes part of the culture,” says Ardeña. “It invades the cultural landscape, and that’s the reason why I use them.”

Ardeña has been making his Ghost Painting: Cracked Category series since 2015, when he moved to Bacolod, on the island of Negros. After growing up in the Philippines and then living in Europe and the U.S. for a number of years, Ardeña was struck, on his return, by the fact that tarps are everywhere, and used for so many different things. “It’s a universal material, but it’s extremely pervasive in both the urban and in the rural landscape in the Philippines,” he says. “Tarpaulins are used to advertise products, but also by families when there’s a funeral or graduation.” During the pandemic, some people would announce via tarps strung up in front of their house that they didn’t have Covid.

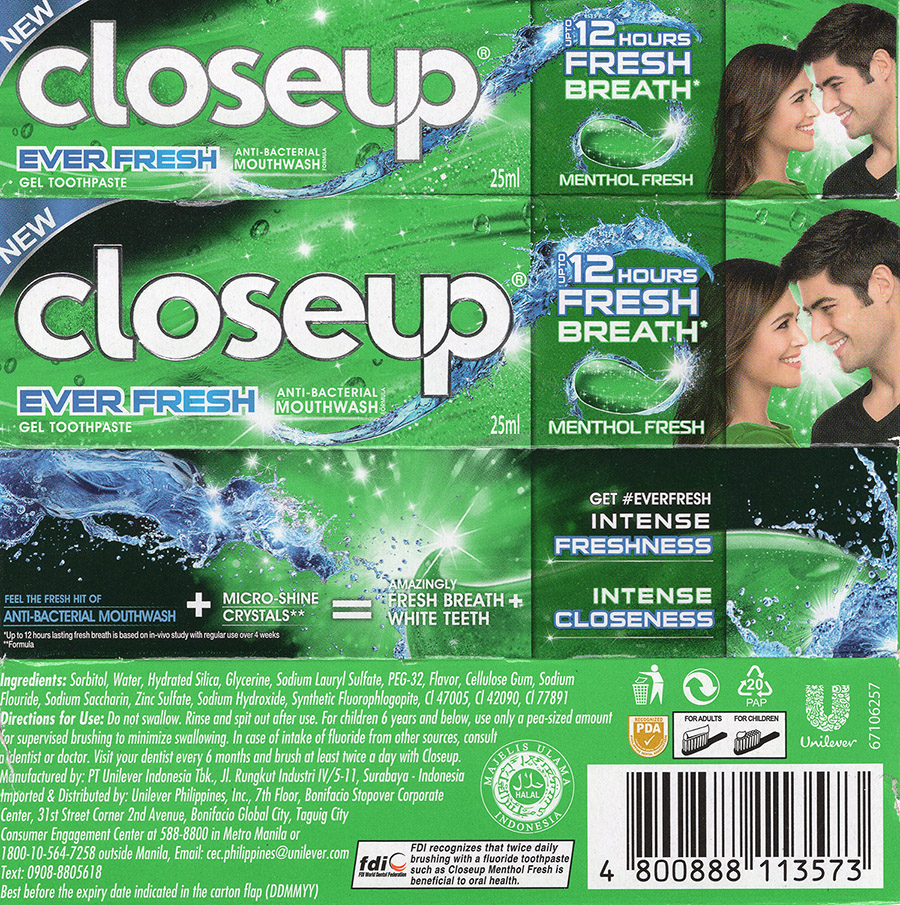

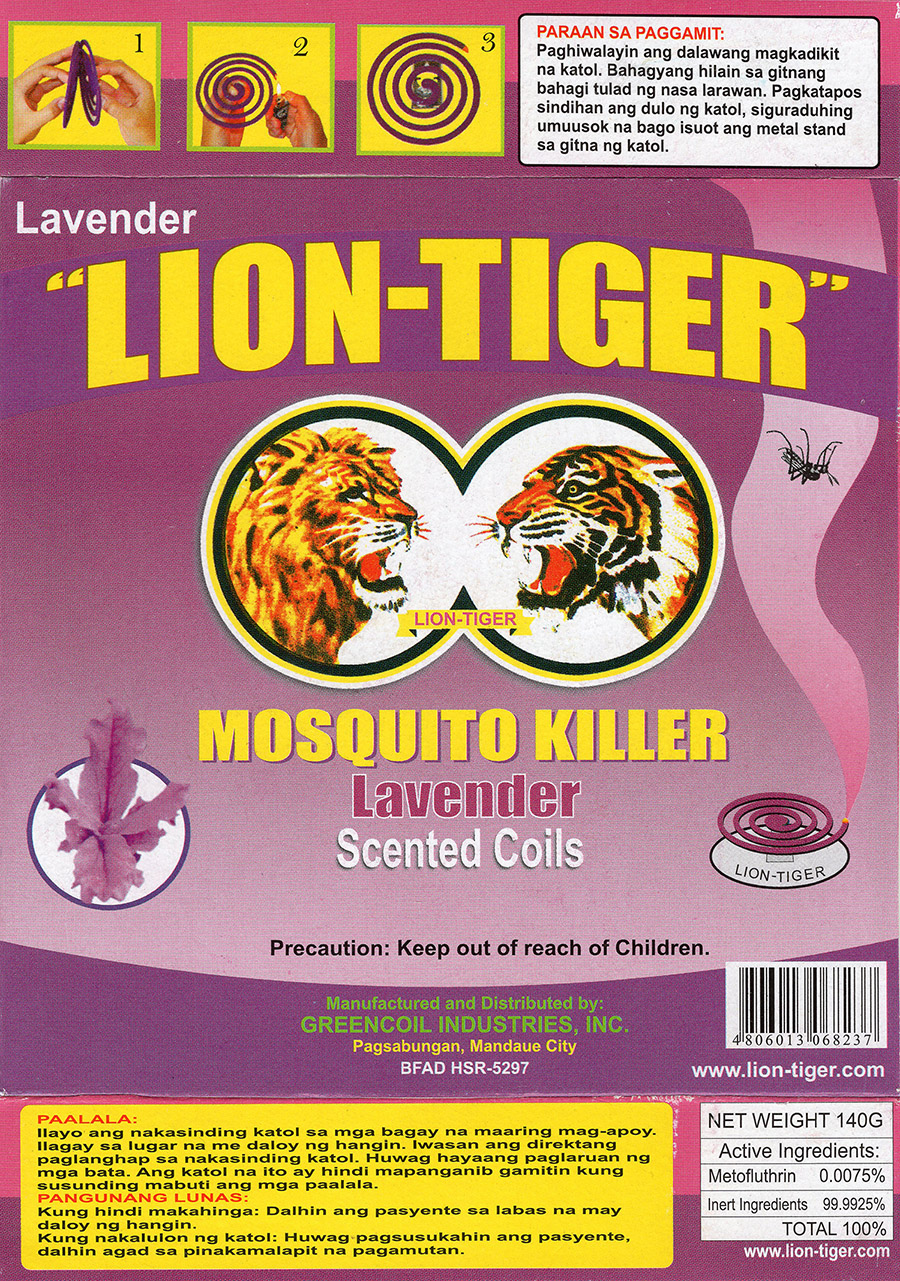

Ardeña first started collecting tarps from the street in the lead up to the country’s 2016 presidential elections, when they were frequently being used as campaign posters. “At some point, I started scanning the products that I’m using at home,” in place of the political images, he said. Ardeña takes the scan to a facility close to his studio, where they print them onto the tarps. The packaging he uses ranges from toothpaste to kitchen appliances, but the bulk of them are food labels.

For his painting Ghost Painting (Cracked Category): HQE Rice Cooker, for example, Ardeña scanned the label of the rice cooker he has in his kitchen. Another painting uses the packaging for the six piece Chickenjoy bucket from Jollibee, which Ardeña describes as the McDonald’s of the Philippines: “everyone loves it here; we all grow up with that chicken.” The Fiesta brand spaghetti used in another piece is eaten on special gatherings like birthdays or Christmas, and the 555 Sardines “is such a Filipino brand,” he says. “It’s not personal, it’s cultural — from your grandmother to the kids, everyone knows the 555 Sardines.”

In the nearly seven years that Ardeña has been accumulating an archive of these scanned images, he’s observed certain patterns in the packaging design — like that the color red is used the most, and the color purple hardly at all. Or that products with a more minimalist design and Latin typefaces are the more expensive ones. But these things don’t influence what he chooses to use; for Ardeña, the only criteria is that they are popular products, the kind you would find on supermarket shelves and in kitchen cabinets. “I think it’s dangerous to romanticize design coming from a place of nostalgia, especially when it comes to cultural identity,” he says. He’s not interested in conveying a specific local aesthetic, cultural history, or quality of design, but rather the material that makes up contemporary life where he lives.

In the Philippines, where “the socio-political and the economic are very much heightened, adaptive reuse is a form of cultural construction; it’s something that’s inherent in people.”

Instead, he chooses material because it’s there, on the streets of his neighborhood or in his own household, ready to be repurposed. And this process of adaptive reuse is something that Ardeña does consider to be an important part of Filipino history, culture, and identity. Unlike recycling, which has a dimension of morality or social consciousness, adaptive reuse is “not a strategy,” he says. In the Philippines, where “the socio-political and the economic are very much heightened, adaptive reuse is a form of cultural construction; it’s something that’s inherent in people, I would say, to just make use of certain things.”

This practice of reuse is something that Ardeña says adds complexity to material culture in the Philippines, from design to visual arts to the everyday interventions. “If you see it from a Western perspective, you might not think it’s as sophisticated, but I think we have to make a paradigm shift,” he says. “The materials that are available to us, the way we use them, how that evolves through time and generation, personal use and circumstance — it’s totally different [than in the West]. And it’s one of the reasons why I love living and making work here, because it’s exciting. There’s so much to see creatively.”

Kristoffer Ardeña will be showing at the Tropical Futures and Rubber Factory booth for Future Fair New York, May 5-7, 2022 at Chelsea Industrial in New York City.