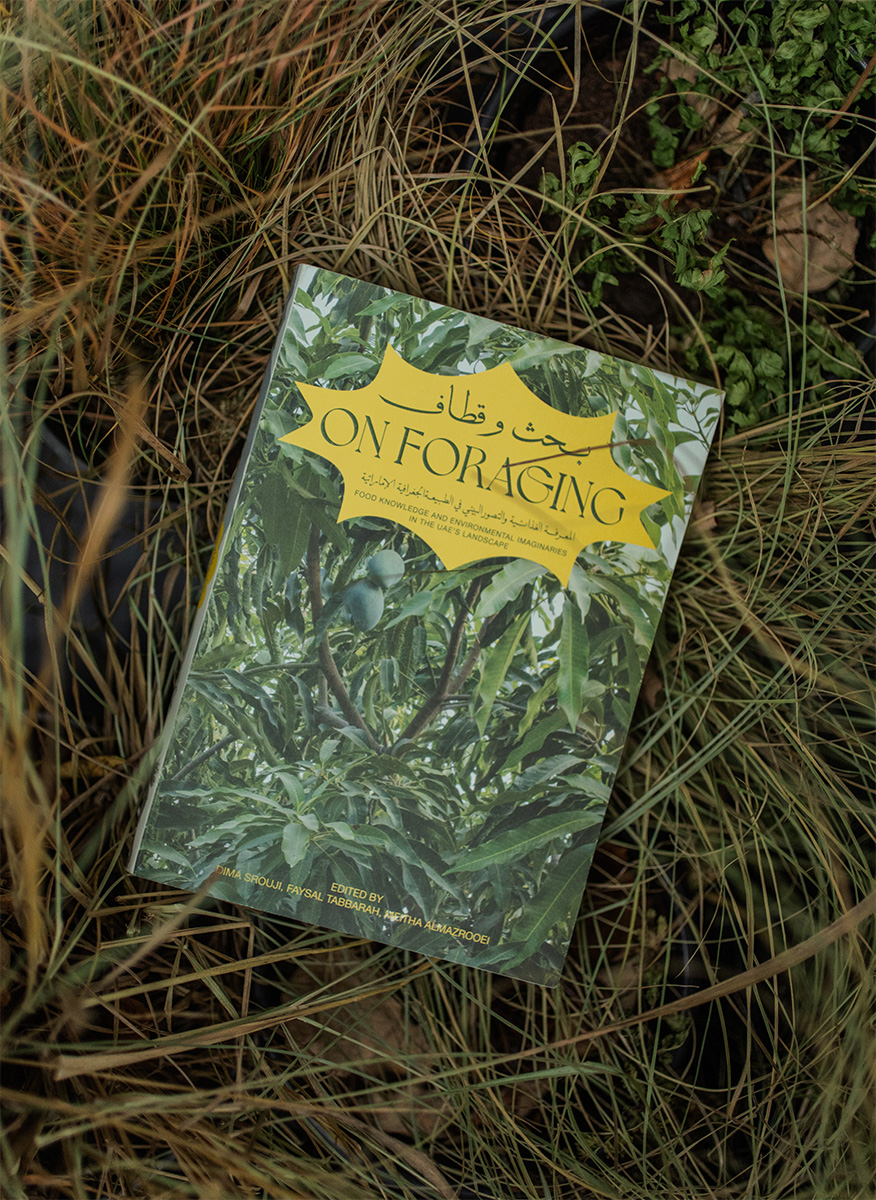

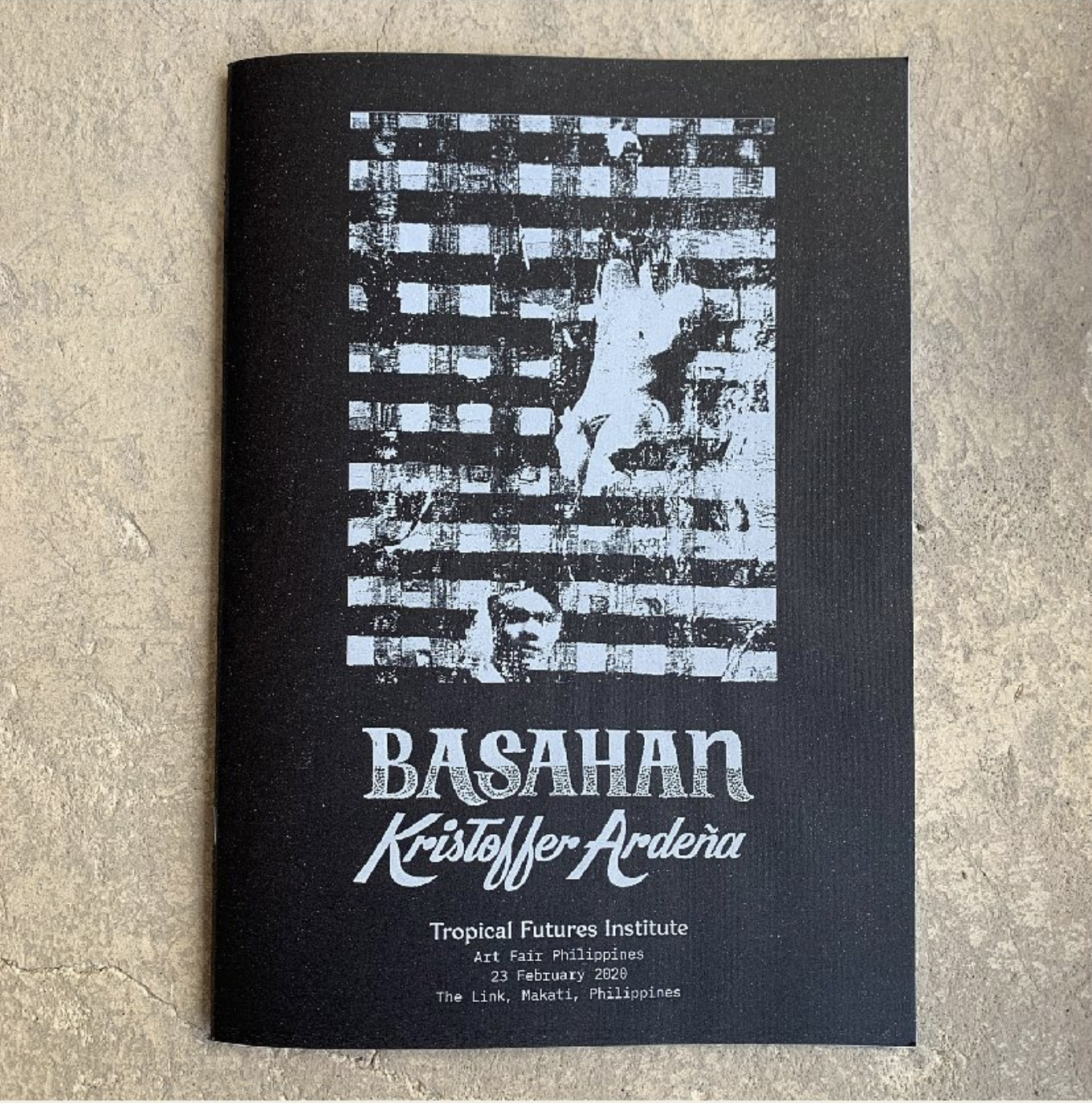

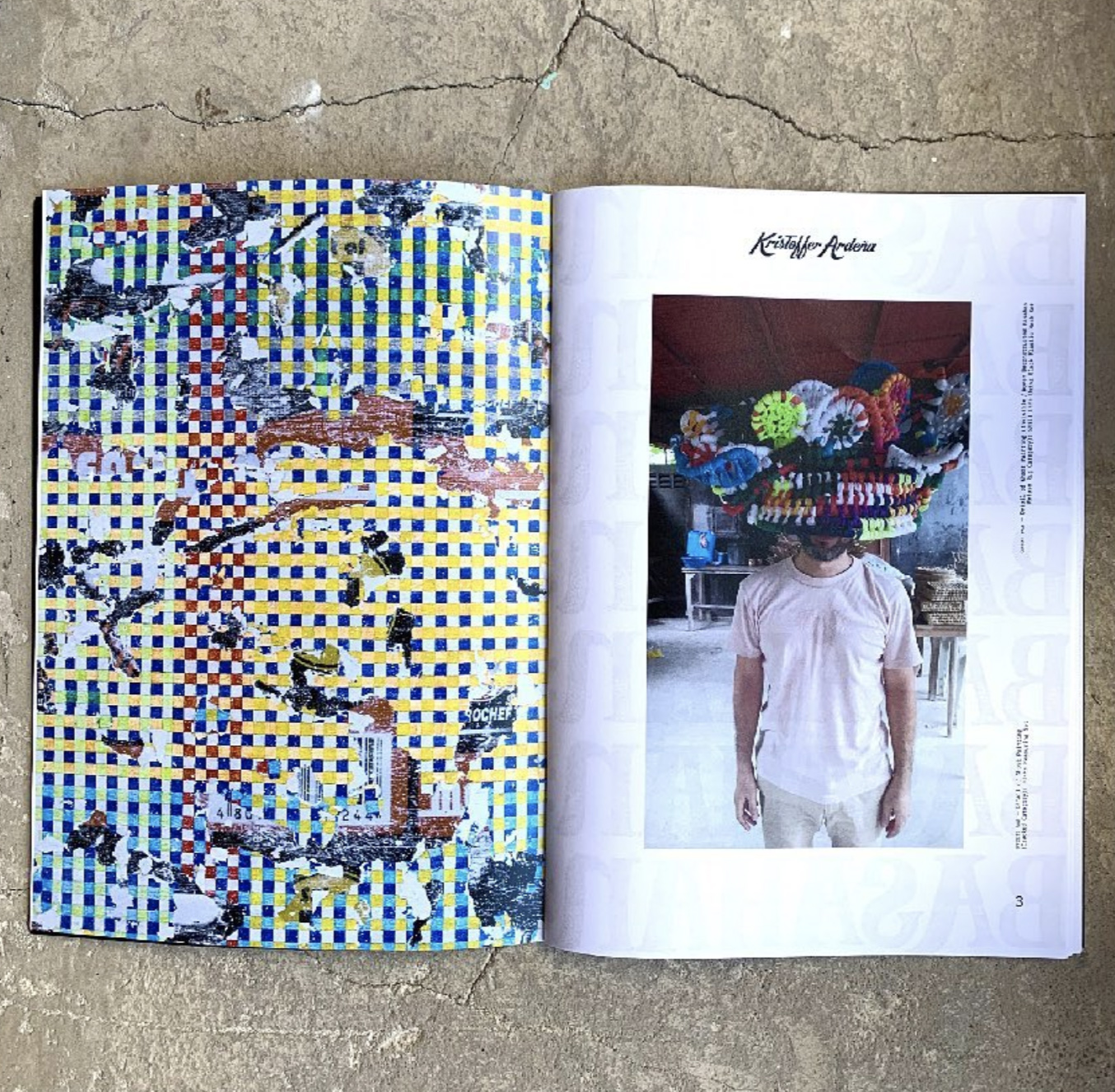

Tropical Futures Institute is the design strategy studio of Chris Fussner, who founded it in 2015 in Cebu, the Philippines. A Chinese-Filipino designer who grew up in Singapore, Fussner worked for six years in New York before moving permanently to Cebu, where he started Tropical Futures partially as a way of connecting to the local cultural scene. As such, the initiative has been defined from the beginning by its collaborations, curations, and gatherings: group shows in Fussner’s mother’s gallery in Cebu, 856 G; the annual Cebu Zine Fest; a residency program for people researching contemporary visual culture in the Philippines; and joint projects with local artists and collectives.

There’s also the studio’s merch line, which is how a lot of people from outside of the Philippines have been introduced to Tropical Future’s work. The “Philippine Love Songs” shirt, for example, was inspired by the design of a 1965 album by Pilita Corrales, which Fussner found in a music museum in Cebu. That visual reference, combined with the use of vernacular typography, celebrates a tropical graphics aesthetic that can also be seen in TFI’s t-shirt collaboration with designer Kristian Henson, and the sarong patterns by Fussner and Zeus Bascon. Or really, in any of Tropical Future’s work — their own output as well as the artists and projects they choose to support and collaborate with. As Fussner puts it in our interview, the overarching idea behind Tropical Futures is to bring attention to the cultural and aesthetics movements currently happening in the tropics, so that the people doing the work within these movements can define them for themselves.

That effort continues today, in various forms and iterations. Fussner worked on the digital section of the Art Fair Philippines last year, and is curating the Art Dubai digital section this year. The pandemic upended some of the projects underway in 2020, but this year he and his team at Tropical Futures will continue supporting projects like the architectural work of Soft Spot in Bohol and community-building non-profit Lokal Lab in Siargao, and showing the work of artists in the tropics. Below, I spoke with Fussner over video call about the cultural and ecological aspects of the new tropical movement, vernacular typography, communal art and agriculture practices in the Filipino countryside, and web3 in the tropics.

Meg Miller:

You started Tropical Futures Institute seven years ago as your own personal practice, and it has evolved quite a bit from there. What was your idea for it at that time, and what has it become?

Chris Fussner:

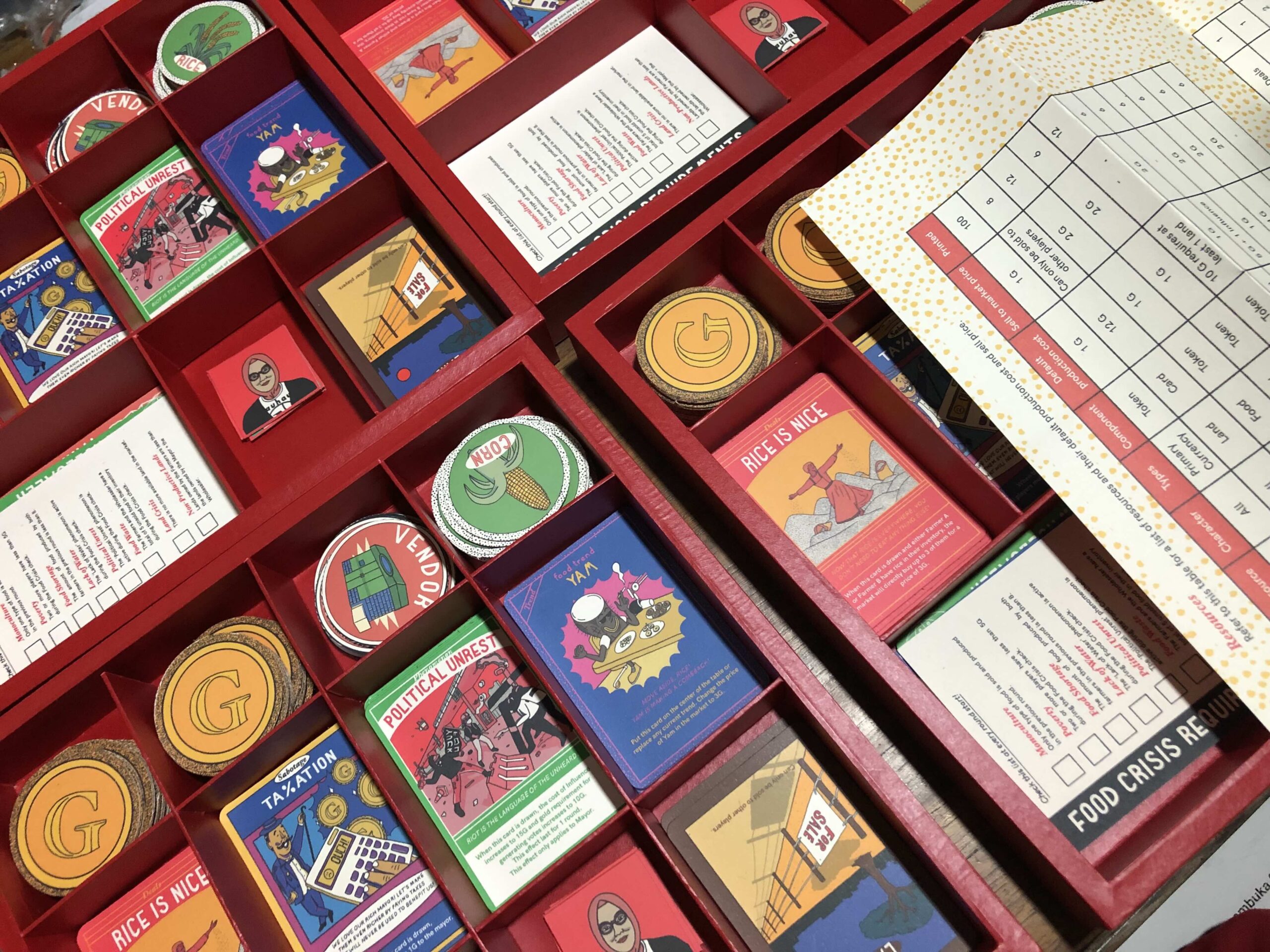

It started when I spent some time in the Philippines with two of my studio mates. We had a studio called VSOON Research Unit from 2013 to 2015, and we did speculative design projects — like, for example, Sari Suki 2050, an installation that used the idea of a bodega store to create and host different futures. We decided to go to the Philippines together and travel as friends, and after that, my focus started shifting more towards the tropics and understanding my own identity related to the tropics. I realized there wasn’t a lot of futuring, or discussions of the future, around the tropics.

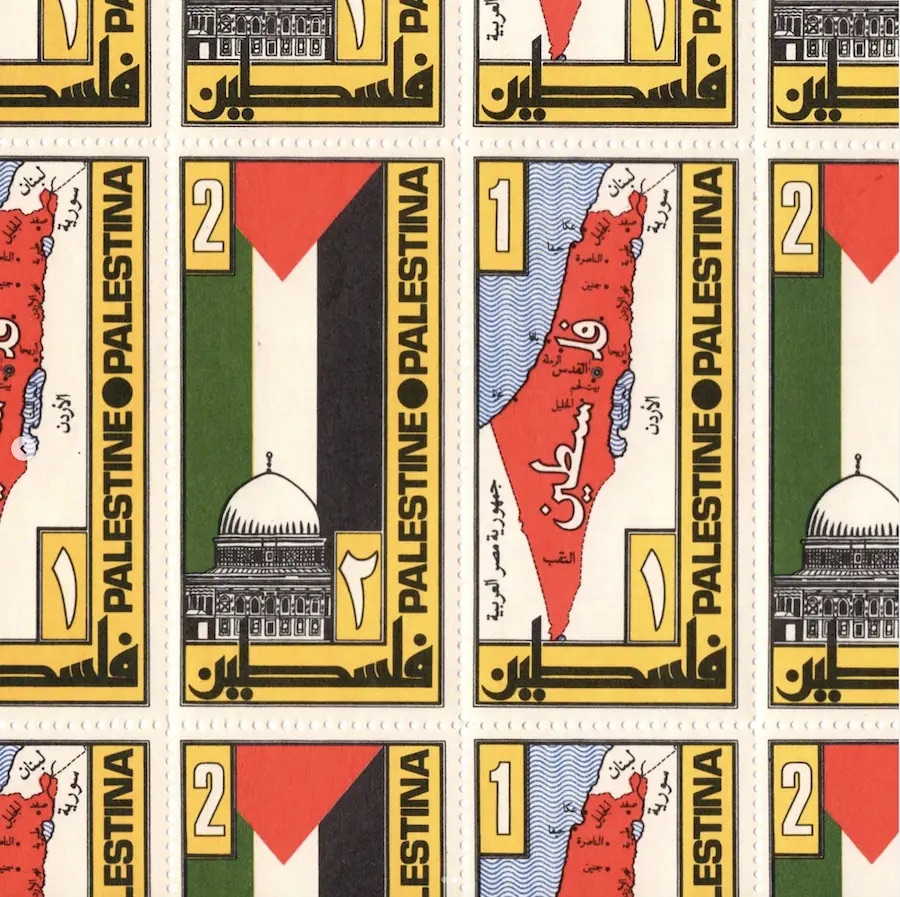

This was during the time when Lawrence Lek’s Sinofuturism video essay had just come out, and there was of course already a lot of interest in Afrofuturism. Now there are all sorts of derivatives, but at the time there wasn’t a lot on tropical futures, so I decided to start the project and call it Tropical Futures Institute. Basically, I just put together three buzzwords, and I used the word Institute because I was a bit frustrated with the lack of contemporary cultural capital in the tropics. The tropics feel very much on the cultural periphery. There isn’t a lot of media coverage and there’s a lack of institutional power; there are great museums and cultural institutes, but still not as many as a Western landscape. And not as many that can make a career, like a solo exhibition at PS1 or MoMA can.

So Tropical Futures started just as a critique on there not being enough talk about the future in the tropics, even though there are a lot of different visions or scenarios that occur within tropics that hold certain views of the future in them — global warming, scarcity issues, rapid urbanization. I also wanted to break away from certain stigmas in terms of how the tropics are aestheticized and exoticized from a vacation perspective. This relates to the Tropical Modernism movement from almost half a century ago, which sought to reinterpret, or own, the contemporary tropical aesthetic at the time. There are contemporary cultural and aesthetic movements in the tropics happening right now, and I thought it was important that the people in the tropics who are doing work about the tropics define those movements for ourselves. Before the Whitney [museum] has a tropical group exhibition or something, and they just land a spaceship and pick and choose what defines tropicality.

MM:

Can you talk a bit about what that looks like in practice?

CF:

In the early days, I was collaborating a lot with friends who were curators, artists, and designers in Cebu. Part of that was me trying to understand what’s going on culturally in the Philippines — I’m Chinese-Filipino, and I grew up in Singapore. After I moved to Cebu and started Tropical Futures, we would organize group shows and put them on at my mother’s gallery there, and organize the Cebu Zine Fest. We’ve hosted so many different events, parties, hip hop concerts, exhibitions. We also have a residency program for people researching the tropics or the Philippines.

The other side of Tropical Futures Institute is my personal design practice. I don’t do graphics so much nowadays, but earlier I was making these graphic T-shirts that were about trying to unlock or understand my own relationship with Singapore and the Philippines.The plan was to use the merch as a bait and switch, but I think it’s still how a lot of people outside of the Philippines know us. It became a way to hold ideas, aesthetics, and stories about the tropics, and reach a wider community beyond the local activities.

MM:

The “Philippine Love Songs” shirt feels like a good example of that — I know you’ve said that it was your way of contributing to a growing awareness of a contemporary tropical aesthetic. I was wondering, how would you describe that aesthetic?

CF:

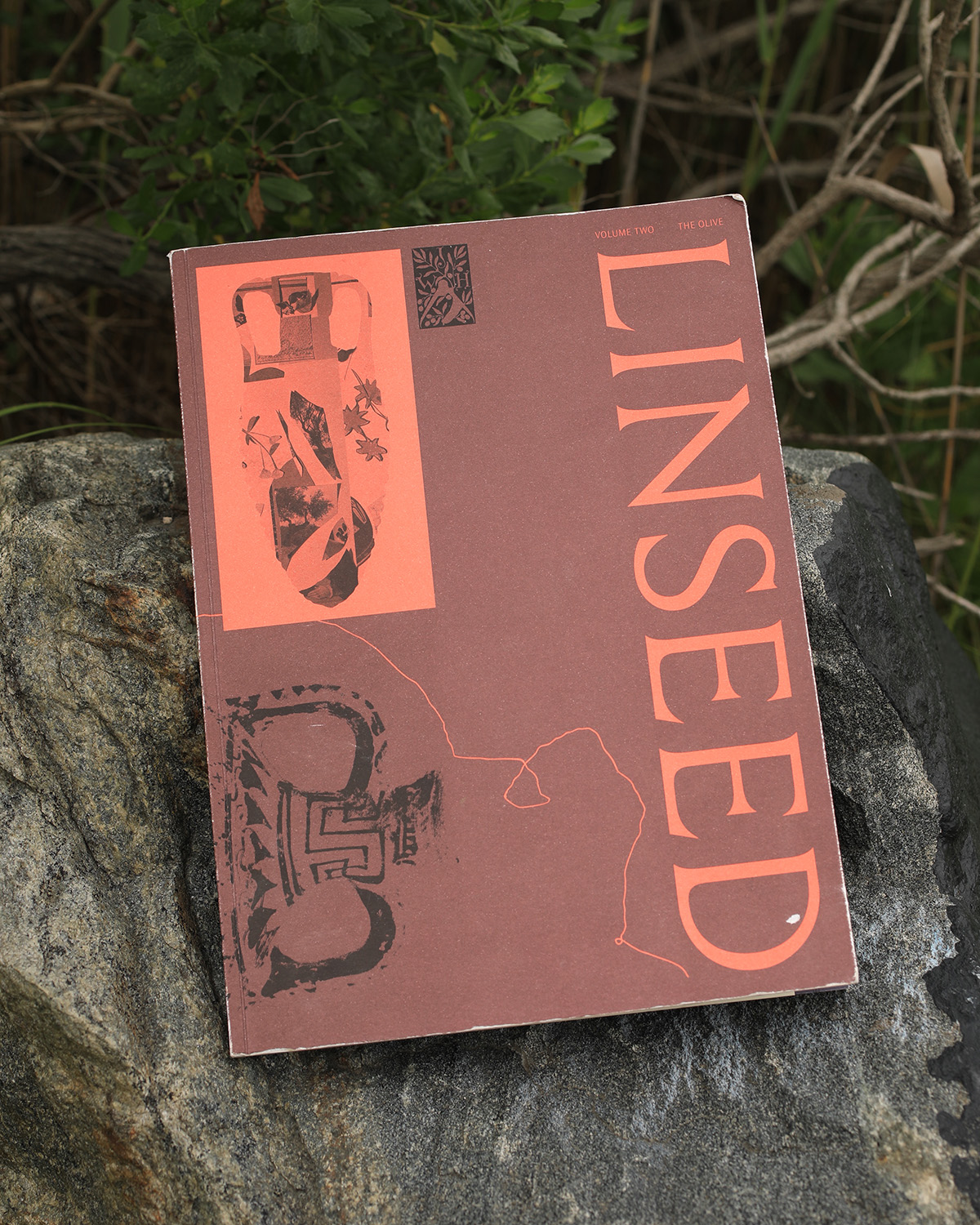

It’s hard to define, but you see more and more designers employing a more vernacular design. In general, there are more fonts now that have a very local flavor and certain graphic styles that celebrate local design, aesthetic, or cultural traits. I was really inspired by Kristian Henson and Hardworking Goodlooking [Henson’s publishing and design practice with Clara Balaguer], and in particular a book they put out called Filipino Folk Foundry. It’s really a celebration of local graphics, whether from sign painting or food packaging, or a reinterpretation of certain historic scripts. Our Philippine Love Song shirt was me trying to understand my Filipino side, and a lot of people resonated with that and found a similar sort of voice in that garment.

MM:

I’ve also seen the term “neotropical” attached to Tropical Futures Institute. What does that term mean to you and the work you do?

CF:

Honestly, I was just sort of taking the piss with these words — with Tropical Futures Institute, for the longest time people thought we were an official Institute and I was getting applications for postdoc research in the Philippines. I’d have to be like “Hey, it’s just me.” [laughs] But “neotropical” is just another way of saying “new tropical,” and it’s pretty broad in terms of what it represents. You’ll see very literal representations of the tropics in juxtaposition to man-made or digital images. You’ll see a dialogue between human and nature, and human and the built environment. I’d also file climatic issues — like how a city is addressing rising sea levels through terraforming, for example — under neotropicality. There are peer-to-peer disaster networks manifesting in Indonesia and the Philippines, which could be looked at as neotropical. Same goes for food security in Singapore, or developing supply chain resiliency in various places. Or even aesthetics like Vaporwave or Seapunk. I would say it goes across that spectrum: from visuals; to looking at the tropics from a historical, post-colonial perspective; to more structural, systemic, and ecological issues.

It was important that the people in the tropics who are doing work about the tropics define those movements for ourselves.

Chris Fussner

MM:

Are there any projects relating specifically to that ecological aspect that you mentioned that Tropical Futures is engaged with or collaborating on?

CF:

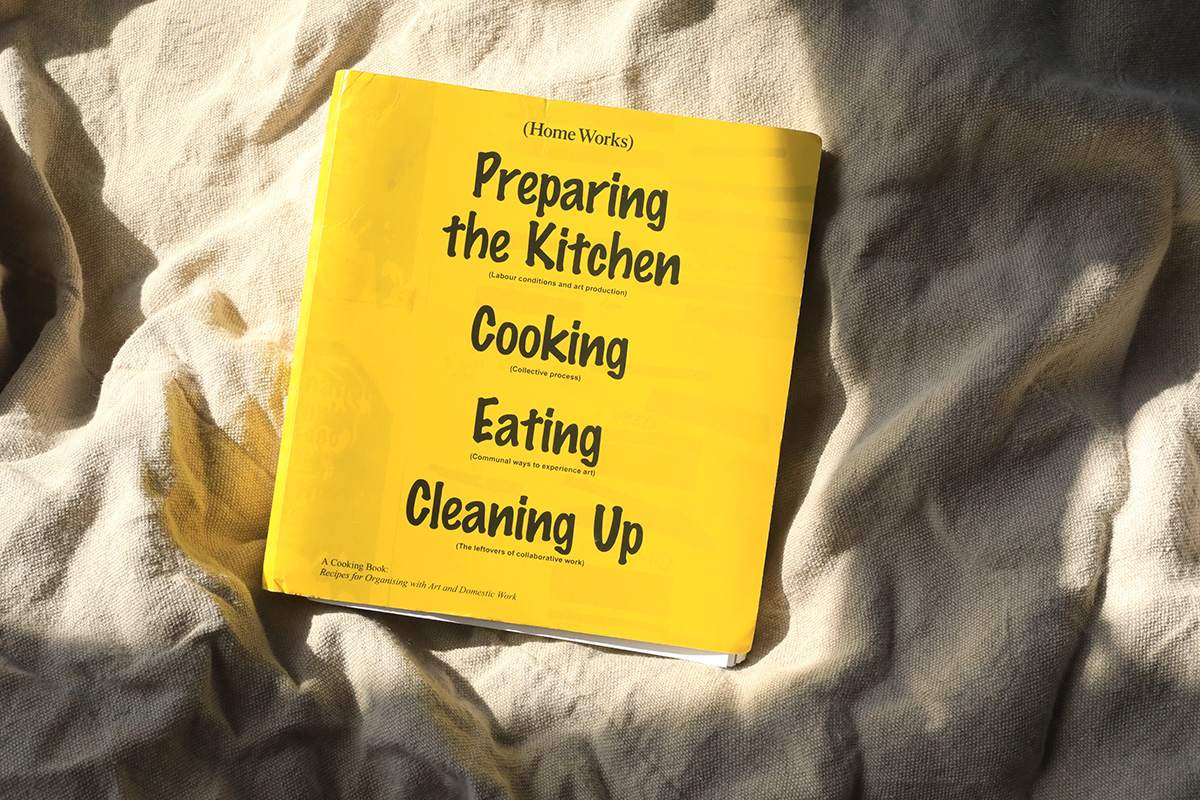

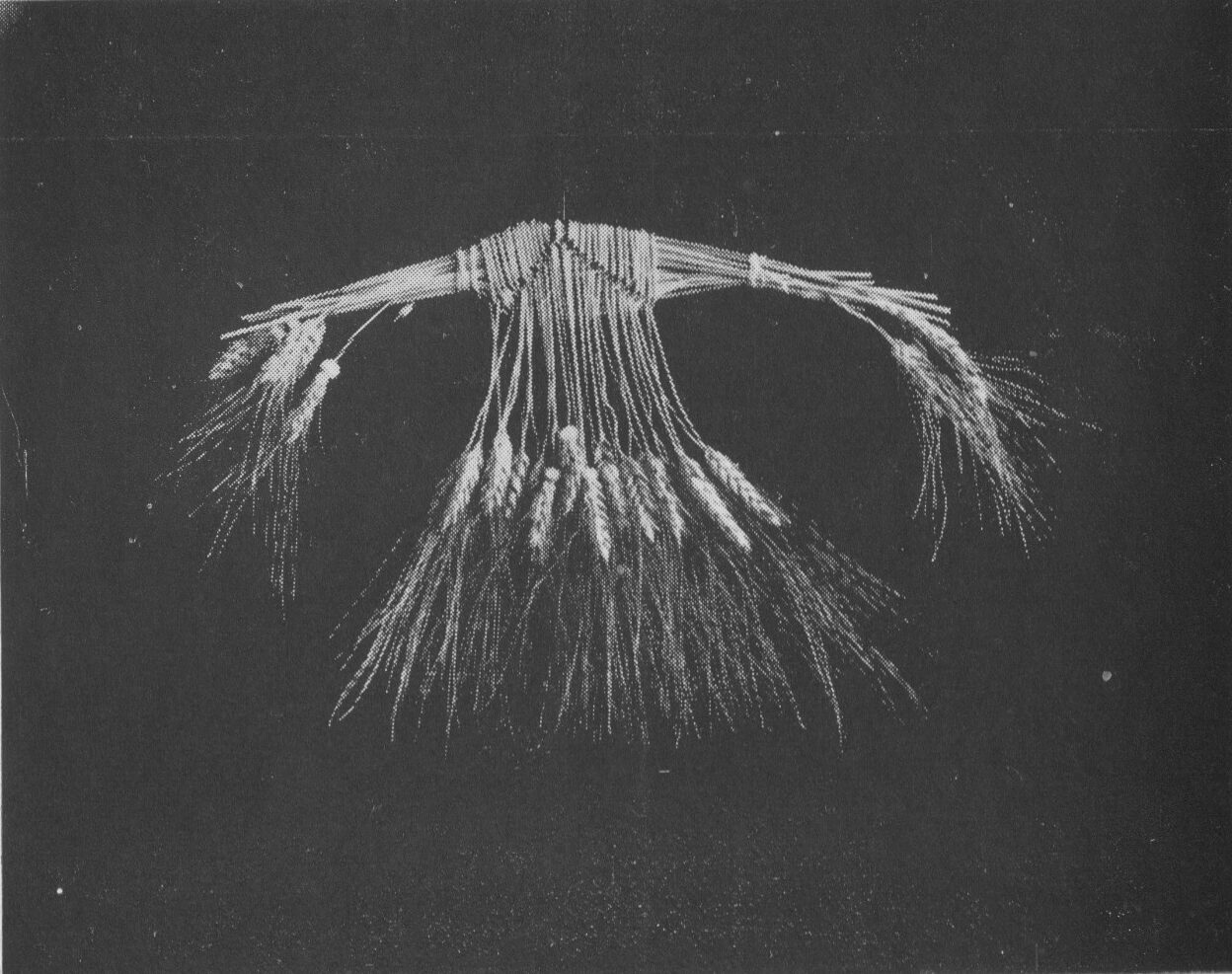

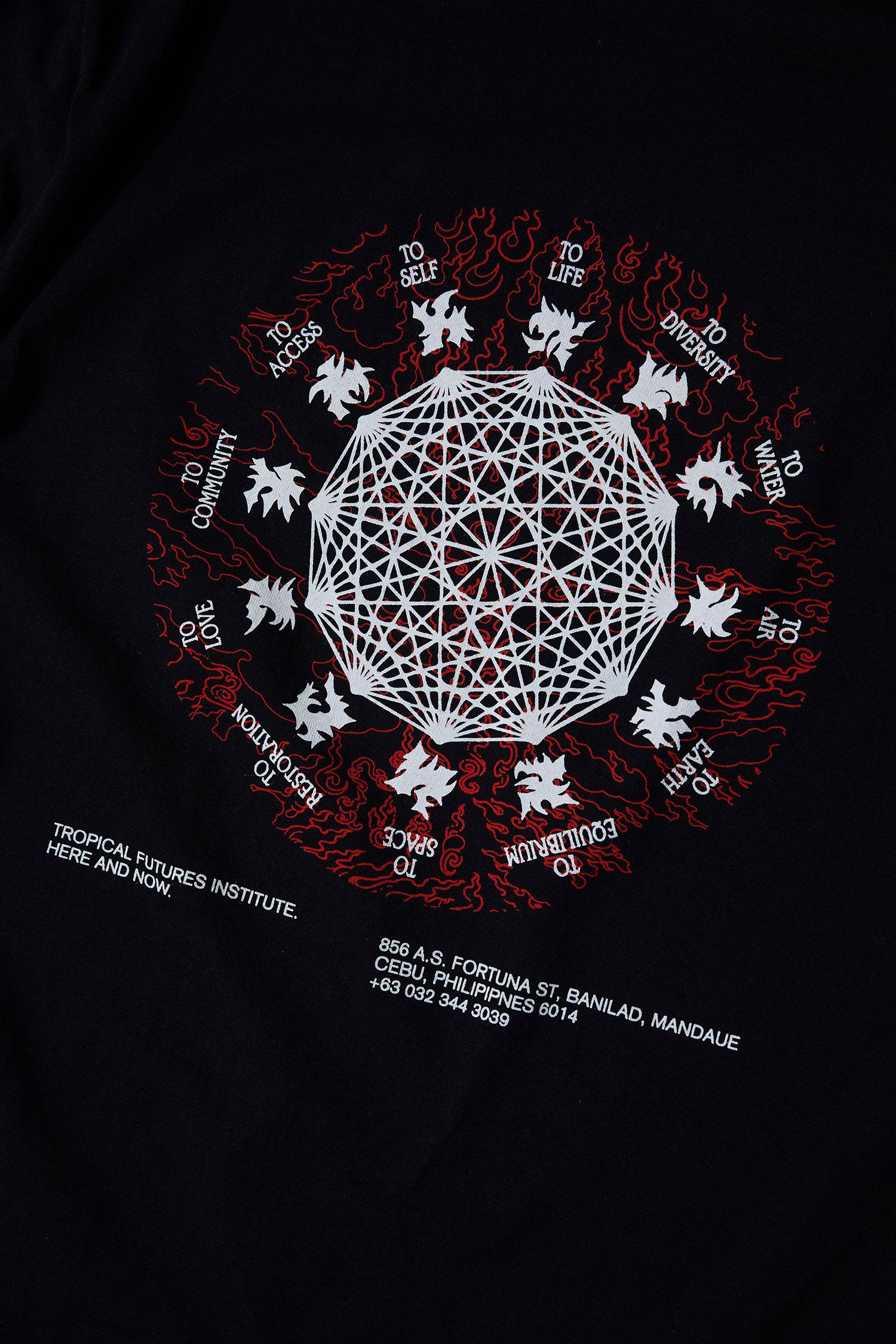

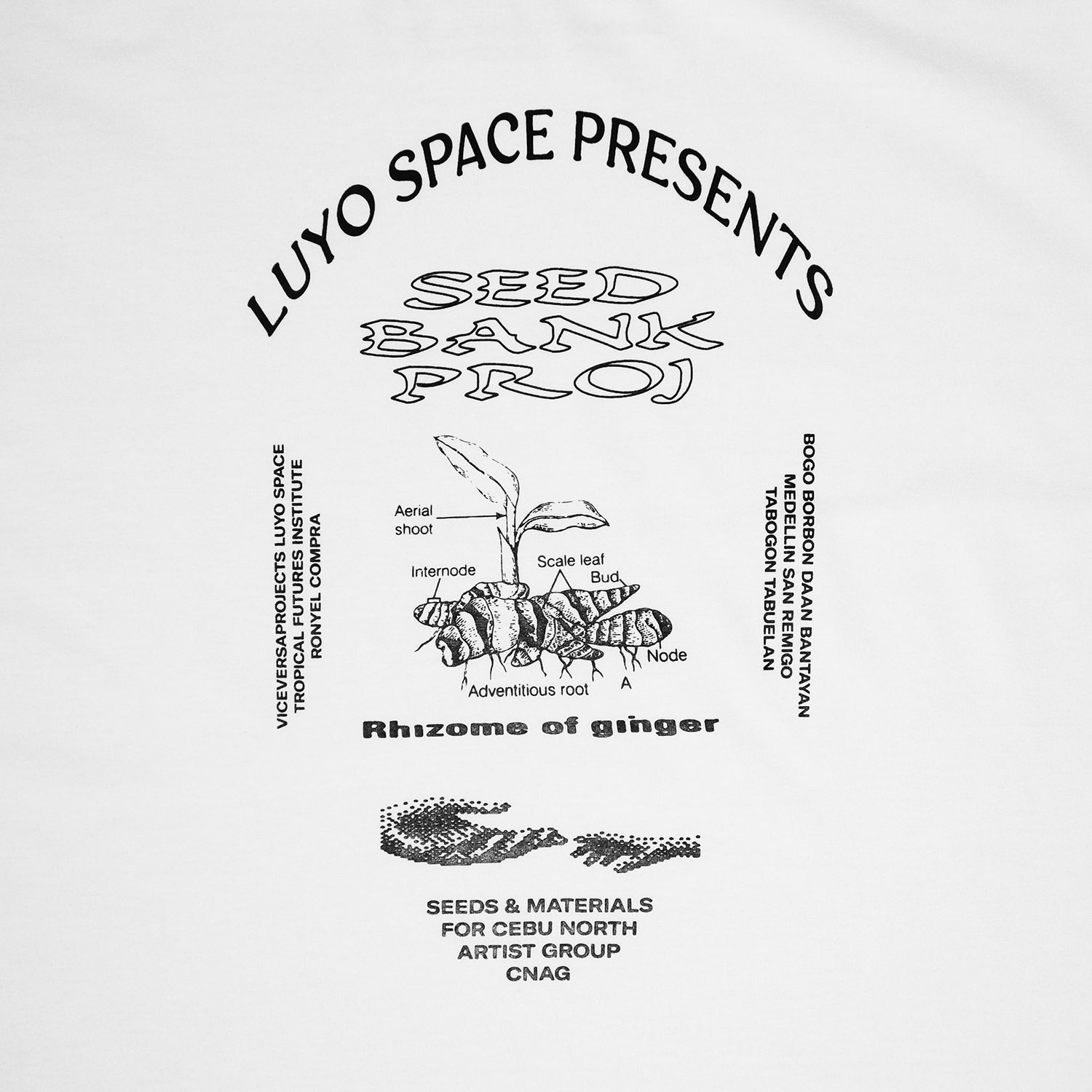

In 2020, during lockdown, we helped raise money for Luyo Space, which was started by artists who, because of COVID, moved from the city back home to the countryside. Their projects deal with permaculture and with disentangling themselves from the global food supply chain.

We had some other projects in the pipeline that related to this area, which ended up falling through because of COVID. One of those is istorya-istorya, a project by Alexis Covento, Jay Carlon, and Angeline Meitzler. And our 2020 resident was supposed to be Mark Pintucan who runs Local Lab Siargao. They work with farmers and local agriculture, do regenerative work, plant nurseries, among other things. The things that Mark is doing are amazing.

MM:

You worked on the digital section of the Art Fair Philippines last year, and are curating the Art Dubai digital section this year. Both of these roles involve education around web3, which I see on the website is now also a focus for Tropical Futures Institute. What is your interest in web3 and how are you incorporating it into the work you’ve been doing?

CF:

I’ve always been into the internet and data — before moving to the Philippines, that had been my focus. I was interested in mesh networks, urban futurism, and data economies, and through that I was introduced to Bitcoin. It was always an interest I kept separate from Tropical Futures Institute, but lately, with this latest crypto cycle, there’s been more cross-over. COVID forced me to rethink how I sustain my practice, and consulting gigs in the web3 space have helped me support the more cultural work for Tropical Futures. The web3 work has been more behind the scenes, but now I’m trying to be more public about it. I’m very much still in the educational space with it; I do my best to answer artist’s questions and connect them to resources.

MM:

What does the crypto art space look like right now in the tropics? Have you noticed anything distinct about it?

CF:

I think there’s not as much techno skepticism in the tropics as in other places, and there’s been pretty fast adoption. Right now it’s still really early, but I’ve seen some cases where artists have had an easier time of breaking out — there’s a lot of red herrings in crypto, but there is also the opportunity to circumnavigate some traditional, very ossified power structures. The crypto art space does exist with its own sort of guidelines and rules outside of the traditional art and design systems. Obviously, there are also artists adopting it to largely their own benefit, but just like with any sort of new technology — whether you’re using it as a medium or as a structure to sell your work — it is definitely creating more space.