The Visuality of Mutuality is a column about the ways graphic design can help support local restaurants, establish deeper roots for food sovereignty, and nourish local food ecologies.

In 2018, which truly feels like a lifetime ago, I ran an interview series with Laurel Schwulst from the kitchen of our shared apartment in Brooklyn. The idea was to invite people we were interested in speaking with to cook a meal together and have a conversation, which we would transcribe and publish to Are.na’s blog (where I am an editor). One of the last ones we did, also one of my favorites, was on the subject of restaurant websites. We spoke with Toph Tucker, a developer whose tweet inspired the topic, and Jasmine Lee, a writer and cook who, about three-fourths of the way through, said something that shunted us out of a discussion mostly about website aesthetics and into one about labor: “So far we haven’t discussed the ‘who.’ We’re talking about these websites, but not the labor behind them. Who do you think is updating a restaurant website?”

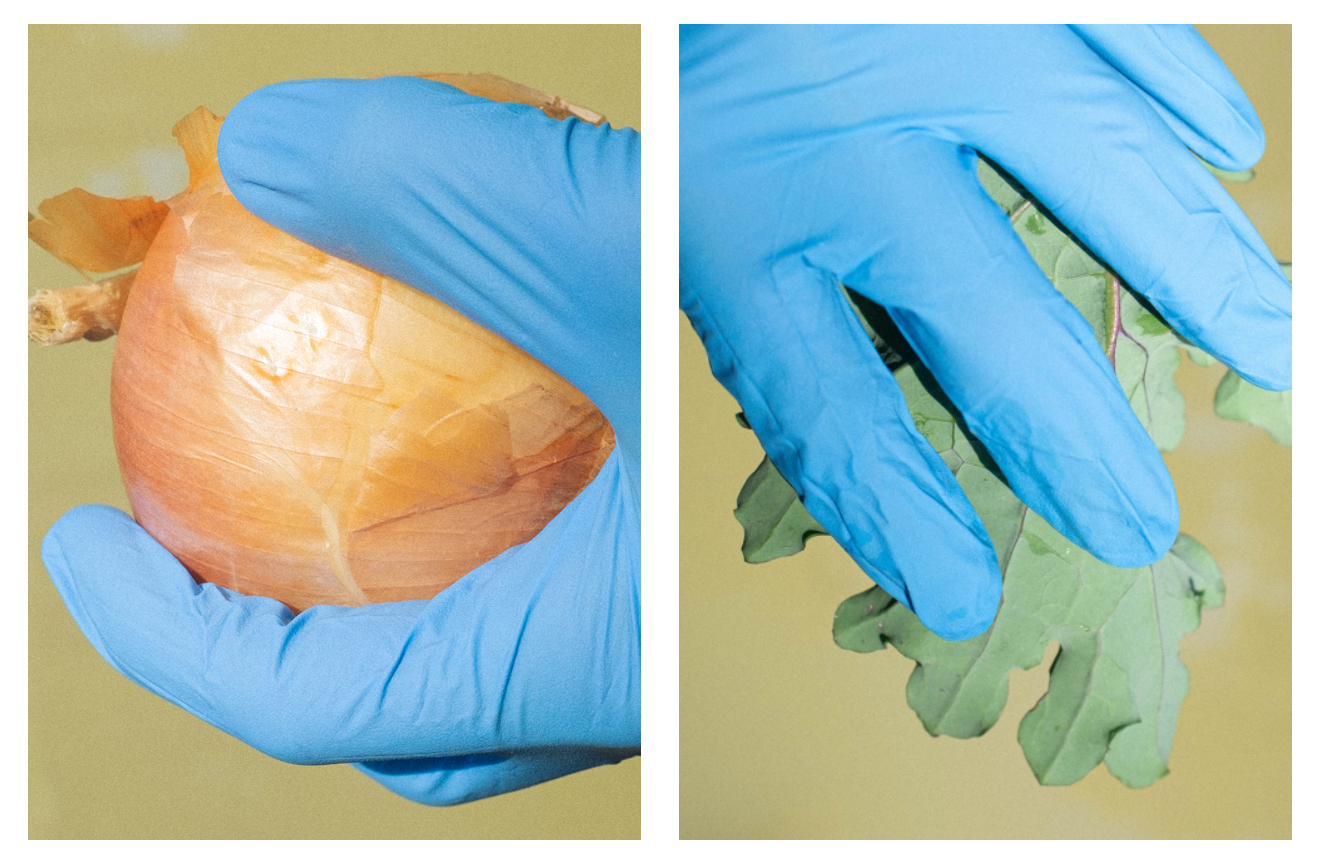

Artwork by Companion-Platform for MOLD

She went on to describe something that will be obvious to anyone who’s worked in a restaurant, but can be easily forgotten on the other side of a well-designed website or curated Instagram page. While a designer or studio may have done the original design work, it’s usually a restaurant manager who’s doing the posting and the updating in addition to the rest of their job, which is to say, running a restaurant. And then there’s social media, which can be “a blessing and a curse,” as Lee put it. “While it reaches a much larger audience, restaurants also become dependent on it to convey their mood or spirit.”

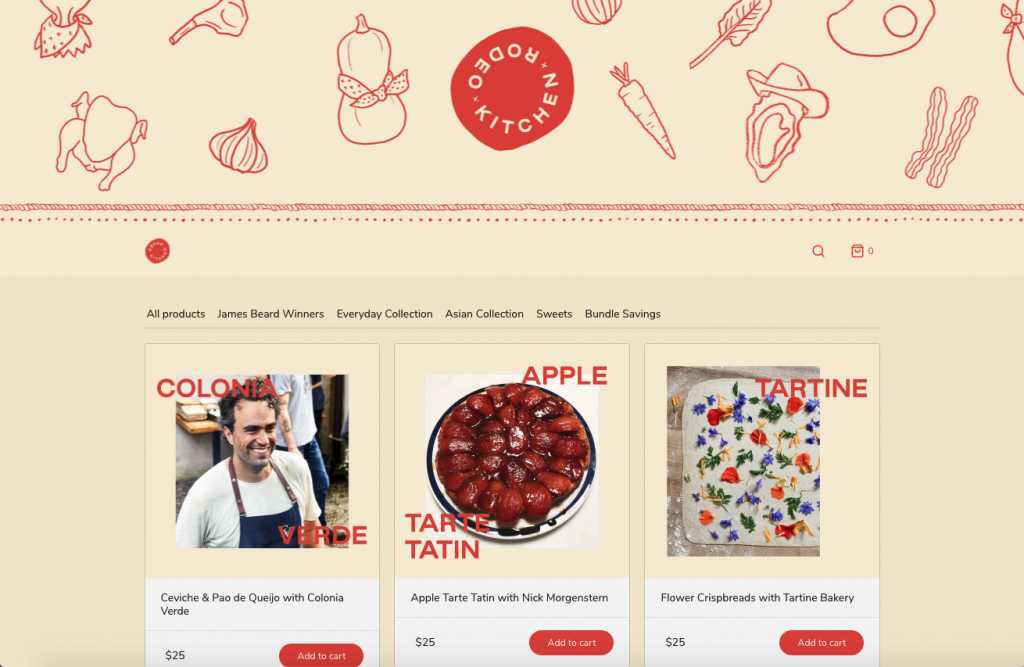

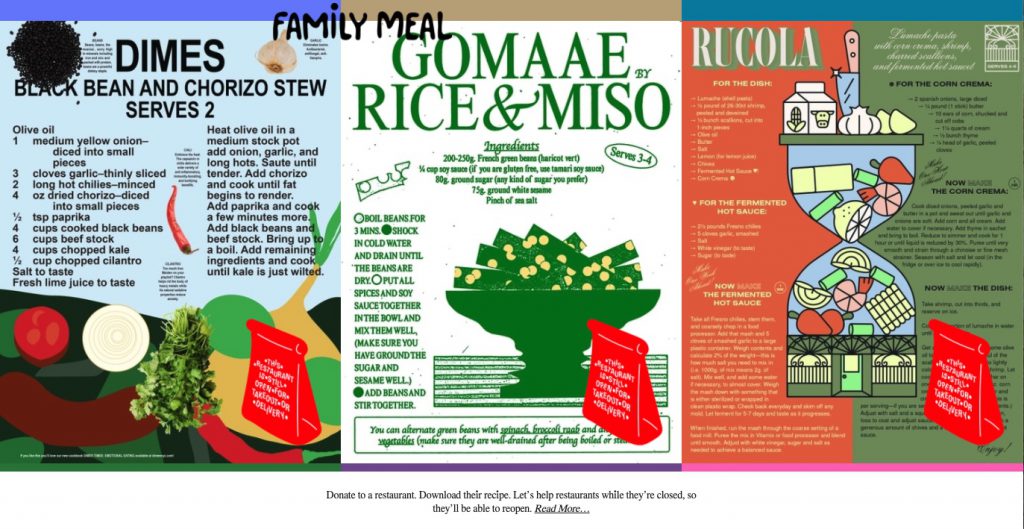

I’ve been thinking about that conversation a lot lately, as the pandemic has shuttered many restaurants and is shifting the normal modes of operation for many more. In today’s context, restaurants have become even more dependent on connecting with people through their websites, social media and newsletters, where they can reach customers, communicate new hours for curbside pick-up, or announce a pivot to delivery. Restaurants have created new revenue streams with finish-at-home meals, Zoom cooking courses, specialty groceries, and merchandise; they’ve banded together to form their own delivery platforms and subscription services. For businesses that are usually so tied to physical, tangible space—lighting, atmosphere, smell, taste—all of that “experience” has had to be translated into digital space and flattened into visuals. While this type of sense-to-sense translation is nothing new for restaurant design, the pandemic has undoubtedly evolved it, expanded it, and necessitated that so much more of a restaurant and its food be communicated digitally, visually and from a distance.

As a design and visual culture writer, I’ve been following with interest the ways restaurant workers (in many cases, still the ‘who’) and designers are using aesthetics and graphic design to sustain restaurants during such a massive upheaval. I’ve also been interested in how our relationships to food more broadly is changing, and I think strengthening, while we’re more or less stuck in place in our homes and kitchens and in our local communities. We’ve seen neighborhood-led initiatives fighting food insecurity, fundraising efforts for local restaurants, an increased interest in growing our own food, community gardens and land trusts. To me, this signals that alternative systems for living together are emerging out of the wreckage of a global pandemic, built on nourishment, sustainability, and care. These are new models and concepts for many people, at the very least they’ve been made new by circumstance, and visuality helps aid our understanding of them. Design allows us to communicate with each other as we build and expand these concepts, even while kept apart.

All of which has led to the central question around which this column will unfold: In what ways can we use communication design to support one another, establish deeper roots for food sovereignty, and nourish local food ecologies? It will be a column about food and graphic design, but it won’t focus as much on packaging and branding as it will on design as a response to a changing sense of community and focus on locality. This is inspired in part by a prompt to designers by John Caserta in an article for Eye on Design (which, disclosure, I also edit):

“If design is a response, there is much to respond to in public. Take a one-hour walk every day (your commute?) to understand the materials, the natural phenomenon, the deeper human relationships that play out in public. Leave the office every day with some cash in your pocket and don’t return until you’ve spent it. Read a book on a park bench. Ask to join someone at their table. Check in on people. Take a phone call while walking as a way to check in on plants, animals, materials, sunlight. Much of this influences or replaces desk work, and rather than connecting you to those far away, being in public helps to knit you into a community that is in continual need of your creative attention.”

I love the idea of community as in continual need of your creative attention. Which brings me back to the restaurants so quickly and creatively responding to a changing situation. The flip side to that are the restaurants that don’t have employees who are brand literate or Instagram savvy—neighborhood establishments that have long relied on foot traffic and word of mouth, and maybe aren’t as nimble to change. As useful as visual design has been to many restaurants in the pandemic, I wonder if it’s also creating a bigger disparity within the industry. And if so, can design be intentionally leveraged to do the opposite?

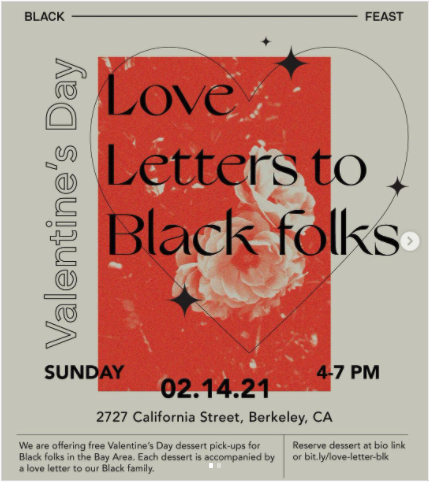

I’ve seen some indications that it can, in the form of mutual aid organizations like Welcome to Chinatown, whose volunteers use design and marketing to help small businesses in their neighborhood connect to customers and sustain themselves during this time. I also think of new initiatives like Salimatu Amabebe and Annika Hansteen-Izora’s Black Feast, and their recent spin-off project, Love Letters to Black People, which offers care packages of desserts—works of art themselves, wrapped in visual art, the whole thing beautifully branded—to Black folks in their communities in Portland. You’ll hear from the founders of both in future columns.

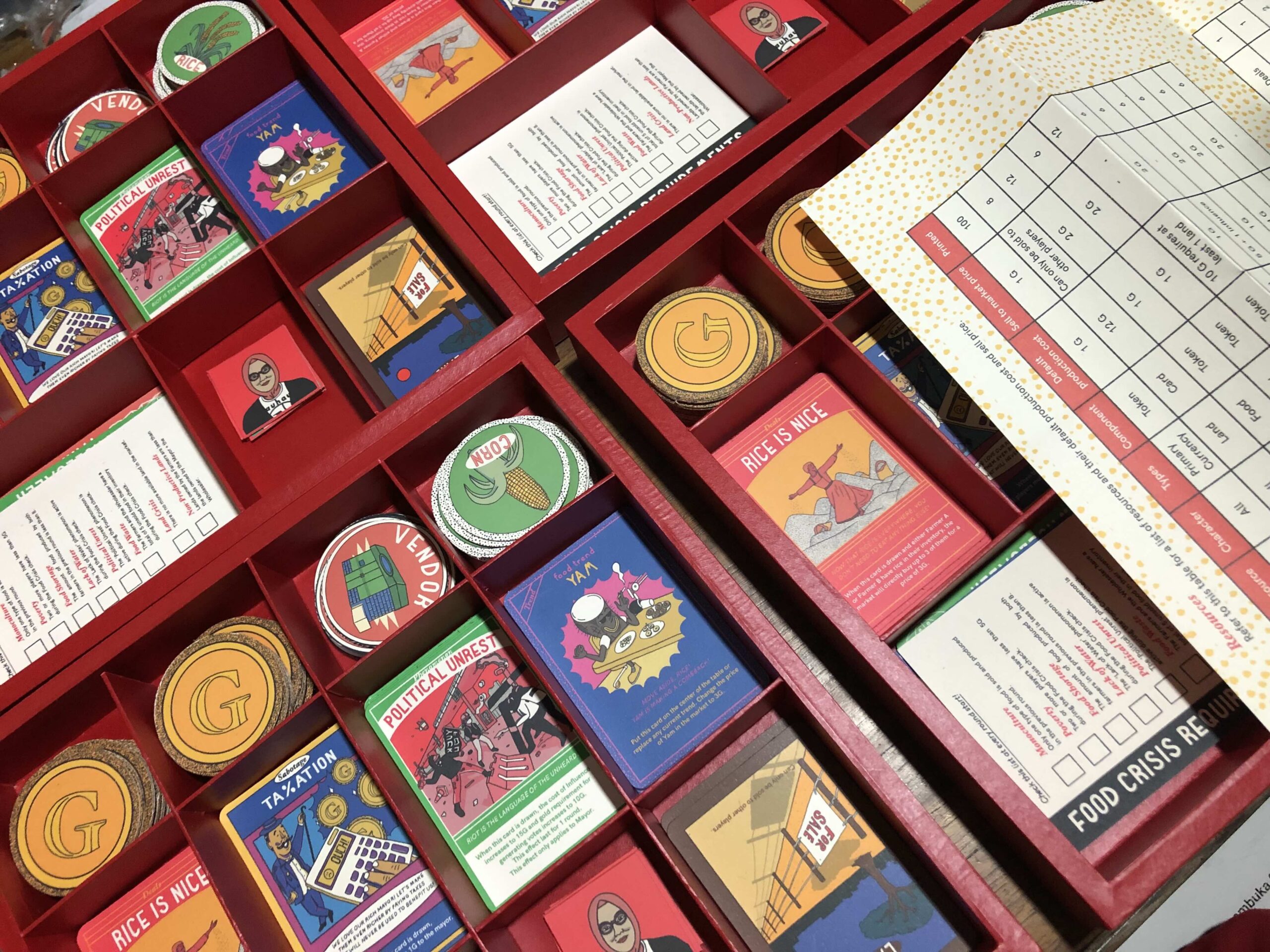

You’ll also hear from designers who are making transparent the global food systems that are purposefully kept opaque. As graphic designer Benedetta Crippa recently reminded me, there are limitations of “going local” in our present economy, which has primed us to expect to be able to eat anything we want whenever we want. In that respect, design can help highlight the effects of a global food industry on more vulnerable economies and help people reevaluate their consumption habits, a topic for another column. As artist Orkan Telhan writes, “design gives us the ability to imagine alternatives, but more importantly it helps us question the morality and ethics of our habits.”

This signals that alternative systems for living together are emerging out of the wreckage of a global pandemic, built on nourishment, sustainability, and care.

And finally (for now) I’m interested in exploring what the design world can learn from the food world—both service industries, both enmeshed in commerce and in art, both grappling with capitalism and global systems; and as a writer and editor, I’m also curious what design criticism might learn from food criticism (see: Alicia Kennedy and Vittles). While sitting down to write this, I revisited a 2017 talk by graphic designer David Rudnick in which he admits his obsession with watching Chef’s Table. These fine dining chefs source their ingredients locally, he says, “so they think about their supply chain, they think about their materials. They get to know the ecological impact of their use of materials…and they also know the ways in which that then has [an effect] on their local community.” Designers also source materials, they also work with suppliers, and they also have the opportunity to think about their craft in terms of locality. But unlike in the high-end restaurants on Chef’s Table, designers “have much more open and broadly sourced points with the public that don’t have to be ultra-rarified objects. The onus is on us to work with these parameters and to make them extraordinary.”