Subject to Change is a series about the anarchitecture of New York City foodscapes and the makers that are designing new ways of working.

Free food fridges have been popping up all over NYC since March as a grassroots response to the COVID-19 crisis. While community refrigerators have been around for some time, strict regulations in New York City have curbed their introduction in New York City. When it became apparent that wide-spread unemployment caused by the coronavirus outbreak would lead to even more severe food insecurity among communities already most affected by years of food apartheid, the Department of Health turned a blind eye to the community response.

Anyone is allowed to stock the fridge. Anyone may take food from the fridge. People can take as much as they need and give back when they are able.” – In Our Hearts NYC

The contents of these fridges vary and are dependent on the needs of the community that they serve. Some of the “Friendly Fridges” activated by In Our Hearts NYC, an anarchist network that is known for Grub Community Dinners and Bushwick Food Not Bombs, are stocked with more than just produce and provide prepared foods, packaged products, and pantry items. However, Zenat Begum, founder and owner of Playground Coffee Shop in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, believes that community fridges have potential beyond hunger relief. These fridges could encourage healthier eating habits and increase opportunities for folks who have been denied access to nutrient rich foods. “Being able to give people [fresh produce] as an option gives them power in choice and more tools for thinking about and making fresh food in their homes. Produce will go farther than a sandwich as far as nutrition and yield. Having a produce fridge, the yield is a lot larger than anything packaged or prepared,” explained Begum. That’s why the Brooklyn fridges serviced by Playground Coffee Shop only offer fresh produce.

Playground Coffee Shop not only serves coffee and a small food menu, it has acted as a community and programming space focused on social awareness since it opened four years ago. Past programming includes the Communion: Black Art Fair, a weekend-long event highlighting the work of Black artists, DJs, and creators, The Playground Writing Workshop, a recurring gathering focused on fostering an open writing space for self-love, boundaries, and refreshment, and Playground Youth’s Dinner With Us, a dining series centered around food justice education, food access, and imagining new food acquisition methods. The space itself, a neighborhood cornerstone, has been in the Begum family for over 20 years. For the last two years, the team at Playground have hosted food justice events that include educational community dinners and a waste brunch, where produce is rescued from groceries and markets and turned into delicious sliding scale meals available at Playground. Now, the community fridge initiative is a crucial organizing effort in a neighborhood where one out of four residents is food insecure and where there is only one supermarket for every 57 corner stores.

IOHNYC’s The Friendly Fridge Instagram appeared in April and has steadily found a following. By June, Begum and her friend, and chef, Priscilla Aguilar joined the fleet of organizers in the city wide dissemination of these community fridges. The two womxn of color took to Twitter and Instagram, asking for volunteer drivers, monetary support, working fridge donations, and bilingual community members. Within days, they sourced enough donations for the first of four working fridges supplied by Playground. The pair collectively pooled support from a network of friends and allies, second hand kitchen equipment retailers, and even Craigslist. Their efforts and the speediness in which they were able to get up and running is crucial for the community. “There are people who are still unable to receive benefits, and are having to choose between paying rent and feeding their families” Aguilar said.

Due to stay-at-home orders leaving many out of work and worried about getting food on the table, Begum stressed the importance of those of use who are healthy and cautious to make mutual aid connections and fill in the gaps where government aid has failed to provide nutritious options. “We owe it to the people who are staying home,” she said.“There is great privilege in our mobility.”

Playground installed the first of their community fridges in front of the coffee shop on June 11th. By June 19th, neighboring businesses such as Sincerely Tommy, a Black-owned coffee shop and retail boutique, and Yafa Cafe, a Yemeni coffee shop, have partnered with Playground to maintain and replenish fridges now stationed outside of their storefronts. And this past week, a new fridge was established at the vegan wellness space, Beauty Strike.

Zenat herself ensures that all of the fridges are subject to a strict protocol. They are routinely cleaned, accessible 24/7 to anyone, and stocked daily with fresh produce often donated from Brooklyn farmer’s markets. She believes access to produce is key to sustaining healthy diets and choices. Providing a way for people to explore new ingredients in this low-risk, no-cost structure encourages experimentation, learning, and hopefully increased ingredient literacy.

“I think that for me, as a person who’s wanting to create a space just for produce is very hard,” Begum said. “Not everybody knows what to do with produce. Not everybody knows how to cook. But can you start somewhere if you see something? Yes. Can you fuck up and try again? Yes. If it’s free, the possibilities are endless. And I feel like when it doesn’t come at a cost to you, there are more things you can learn.”

Increasing access to unfamiliar ingredients excites Begum and is something that everyone from young Bed-Stuy creatives to long-time residents can get excited about. “As a person who grew up on bacon, egg and cheese sandwiches and deli food, I can’t tell you how many times I was envious, or wished I knew how to cook food earlier,” she said. With three weeks in action, Begum reports the fridges are getting completely cleared out, including the ingredients that people are most unfamiliar with.

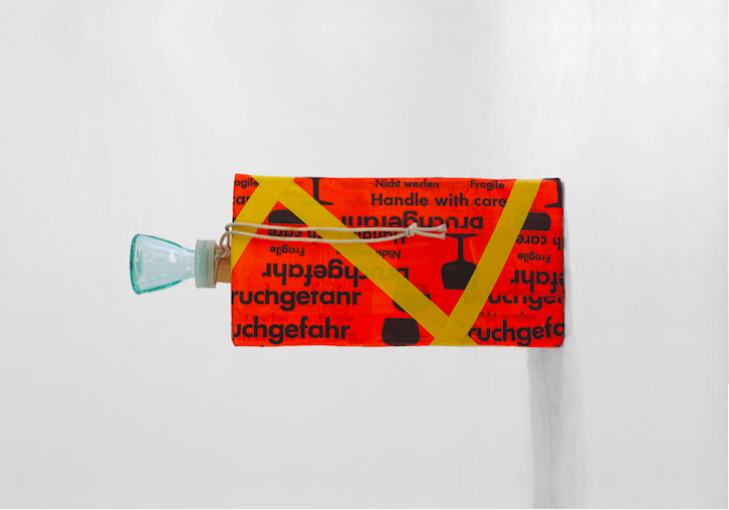

Begum and Aguilar believe their cultural sensitivities to be incredibly important when addressing the politics around free products. The duo has addressed concerns around the spread of the virus and overall safety of sharing products with a vehement dedication to cleanliness and temperature control and a vigilance against spoilage. And most importantly, they are conscious of the ways that power dynamics and histories of gatekeeping in food play a role in the accessibility and potential hesitancy surrounding free food in poor, Black and Brown communities. “Just because it’s free doesn’t mean it has to be ugly,” Begum said. With this mantra in mind, the fridges are stationed in plain sight, and free of any locks or obstructions. They have been given colorful makeovers, don cheerful expressions thanks to the work of local artists, and even have notes in Spanish and English explaining their purpose, upkeep, and contents.

The community has responded with great feedback and visible excitement for these fridges. Which is not to say the needs of the community can’t change. Begum’s confidence in herself, her team, and a communicative feedback loop is vital to ensuring a cooperative ecosystem of trust and aid. As for those activators who are just becoming involved in community work for the first time, there is a list of things to do before assuming any roles within a larger community: contacting established organizers with existing programs, asking how you can help before acting, and considering monetary support if you have the means.

When asked how she plans to maintain the momentum for the project, Begum emphasizes that this isn’t a new concept to her and her team. “You put the necessary systems in place, and keep your mission clear. These are community practices we’ve had for so long now that are coming out to play. This isn’t a new concept for us. It’s not a trend that is going to just die out. We’ve been caring for our communities like this before this moment.”