It’s early August in Lessac, France. This far into the dog days of summer most are lounging in shady parks or taking a day trip down to the beach, but in the middle of Domaine de Boisbuchet’s 150-hectare campus nearly 50 people are working diligently to lay thousands of bricks.

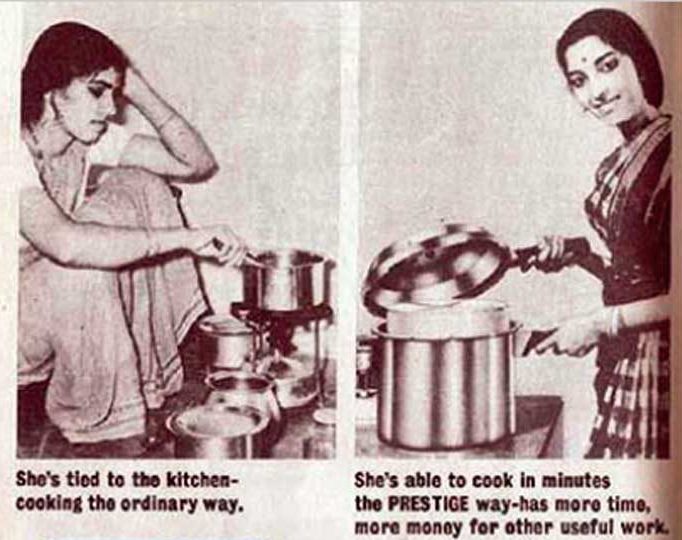

Domaine de Boisbuchet is an international research center for design and architecture in the southwest of France. Each year, Boisbuchet hosts several week-long workshops taught by architects and designers from all over the world, ranging in topics from solar energy usage to seaweed as building material. This August, Sam Chermayeff taught a workshop at Boisbuchet on the production and usage of ovens. Sam is an architect and designer whose work engages in a wide range of projects from furniture to multiunit housing projects; but, as he told me, he also has a special interest in kitchens and appliances and the opportunity to engage in haptic conversation with objects and spaces. So when Sam was invited to lead a workshop at Domaine de Boisbuchet, he asked “Hey, do you guys need an outdoor oven?”.

This week I sat down with Sam to speak about this project at Boisbuchet. We spoke about collective design, the appliance as a body, and the trouble with purity in the built environment.

Madeleine Young:

Tell me a bit about how you and your students came to the decision to build an outdoor oven.

Sam Chermayeff:

At first, we decided to create an event in the middle of the forest and build an oven. In my mind I was thinking about making one out of natural clay we could dig out from the river nearby, but very soon we realized we could build a tool to be used regularly on the property. So, my students, who quickly became my colleagues, decided, “Let’s make a proper oven”.

We had some real limitations because we only had a week and had to get to work. So we all began drawing and collaboratively designing, figuring out how to move forward. We ended up designing and building a pretty large brick oven. It’s a dome, the inside wall has a diameter of about a meter. It turned out that we laid about 3,500 bricks in four days. All of us had very different levels of experience, too. Some people were designers and architects, others were bakers and chefs. And we ended up staying up all night in shifts. We had music playing, and it became a nightclub/bricklaying/baking party all at the same time.

MY:

It’s interesting because in your independent work you’ve mentioned that you’re designing kitchen spaces to celebrate human-to-appliance relationships and become places of gathering, but here the production of work is a gathering and point of interaction with appliances in and of itself.

SC:

Yes, and it was so awesome in that regard! The oven took on the character of the party we were having as we built it. There were certain moments where the heights [of the brick structure] didn’t exactly meet, and I think I would redo it to make the door bigger and the chimney detail slightly better, but that’s not really part of the story…

“It was so good this collectivity, it really worked. I’ll be clear, I’m not saying it’s perfect but part of it was that we did it all together— so certain considerations were made and others were not.”

We just had the floodlights and the stereo, and we laid bricks until 5AM in the morning. We saw the sun rise and then sparked up the oven. It was a really small fire, because you need to cure the oven first, but we started a little fire and cooked some things and roasted some marshmallows. We finished it and closed it—it felt very ceremonial.

MY:

I think it’s also very poetic to be lighting the oven as the sun is rising. It’s as if you are giving the final breath of life to the body you have been collectively working on.

SC:

Absolutely. And bricks are a great thing to build with because they are all about the body and hands. The reason why they are the size they are is so that one person can lift and lay them. Everybody can lift one and lay one right there, and even though they’re all over the world in giant things, they’re actually starting from a very economical place.

MY:

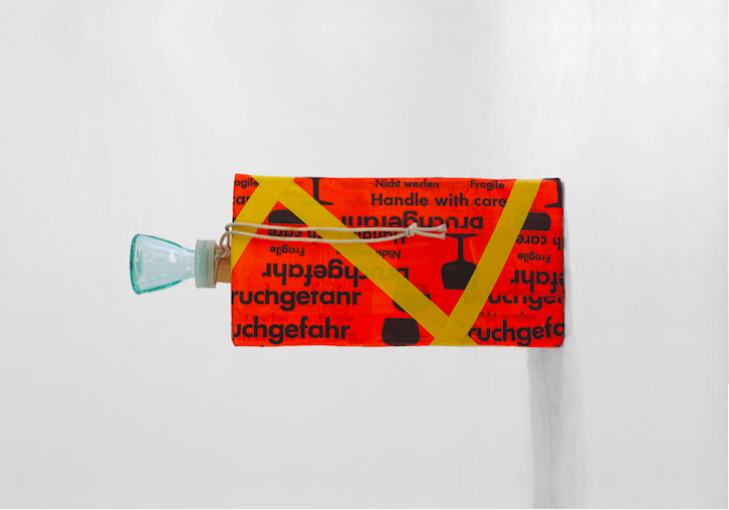

When you described the workshop, you quoted Mary Douglas in ‘Purity and Danger’, where she wrote “Where there is dirt there is system.” I find the conflicting interests of cleanliness and purity great grounds for work in my own pursuits, but I’m also considering how you were laying bricks outdoors, in the mud and dirt.

SC:

I think that it starts from the basic idea that once you start thinking of things in a rougher way, and free yourself of [the pressures of] perfection, you’re able to make things that you can relate to better. Cleanliness and systemization separates you from the human-ness of these kinds of processes. We think we can’t make or understand an oven, but you can take ownership over it and it makes that process much more accessible and potentially more meaningful to you.

MY:

Yes, and when we think about the oven at Boisbuchet, I imagine there’s some fingerprints in the mortar, since you were laying these bricks with your hands.

SC:

Yes, I mean there’s more than fingerprints, there’s actually wonky bricks and the whole oven is full of funny moments like that. These moments wouldn’t exist if this project had been done differently, but it makes it more beautiful and relatable.