There is a new, increasingly popular object in urban Indian kitchens that’s hard to miss. Large, sleek, and visually at odds with almost anything else that it typically sits next to—usually heavy steel pots and pans coated in patina — it is the Instant Pot. I’ve even seen it sitting on spotless marble counters, half clad in decorative fabric. When modern technologies have sartorial style in India (TVs in the 80s and 90s, and bulky desktops had mini wardrobes of their own) it indicates a simultaneous worship and alienness of the newfangled appliance. These sentiments are folded into the practical narrative of preventing them from native dust.

The current treatment of the Instant Pot indicates that the technology is here to stay, much like its ancestor, the pressure cooker, that came before it. The pressure cooker until very recently, was something no Indian could do without. Chinmay Tumbe writes about it as an essential element of the migrant suitcase, despite the parsimonious weight allowance for international travelers. I know from my personal experience of living in the US, that my cooker’s daily whistles were an audible confirmation of an Indian in the building. Sometimes a source of fascination and at other times an object around which a racist discourse would ensue, the warmth —both emotional and gustatory—the cooker provided always came at a cost. The risk of a burn, thanks to an erupted dal or sambhaar, was no doubt, the most severe.1

The Instant Pot is everything the antiquated pressure cooker is not: efficient, electric, safe, sleek and silent. There are even Facebook groups, where Indian women participate in large numbers, to praise its life-giving forces: primarily more leisure time for the main cook. They say you can make Texas-based Urvashi Pitre’s onion-free, keto butter chicken while watching Netflix.

Everywhere it is found, the Instant Pot conjures up the idea of being in with the new. The owners, are in turn, marked with a progressive modernity which aligns with views prescribed by Western global culinary trends. In 2019, the food writer Vikram Doctor made the link between the technology and modernity official. “Goodbye, pressure cookers: It’s now time for electric Instant Pot to dominate Indian kitchens” he wrote in a piece for the Economic Times. Although the technology was invented a good nine years earlier, and subsequently embraced by thousands of Indians in the West2 —including the culinary goddess Madhur Jaffrey —urban Indians in India, Doctor noted, were finally catching on.

- 1.Pressure cooker burns are the highest ranking kitchen accident, disproportionately affecting Indian women.

- 2. The chef/author Priya Krishna even wrote about her aunt “ceremoniously throwing out her pressure cooker”—a family relic—to make room for the new tech.

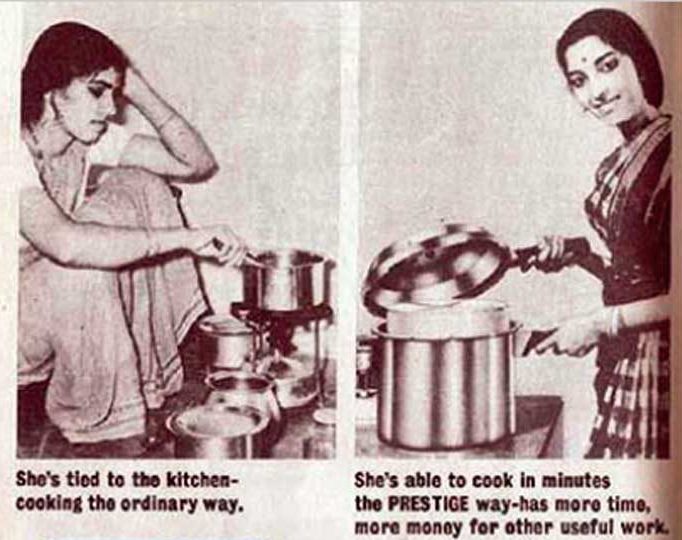

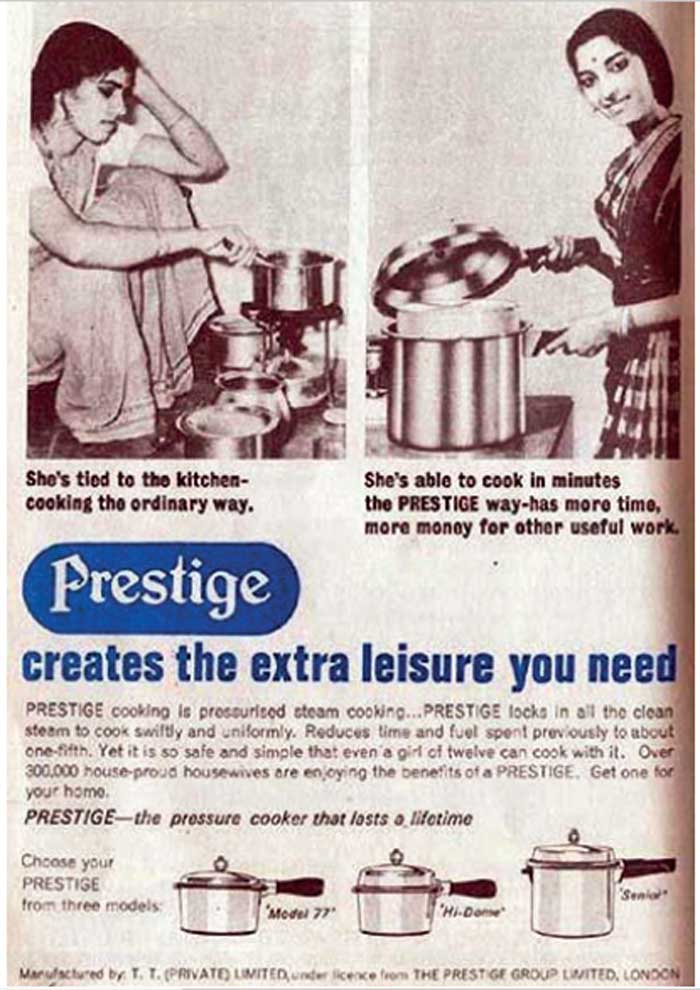

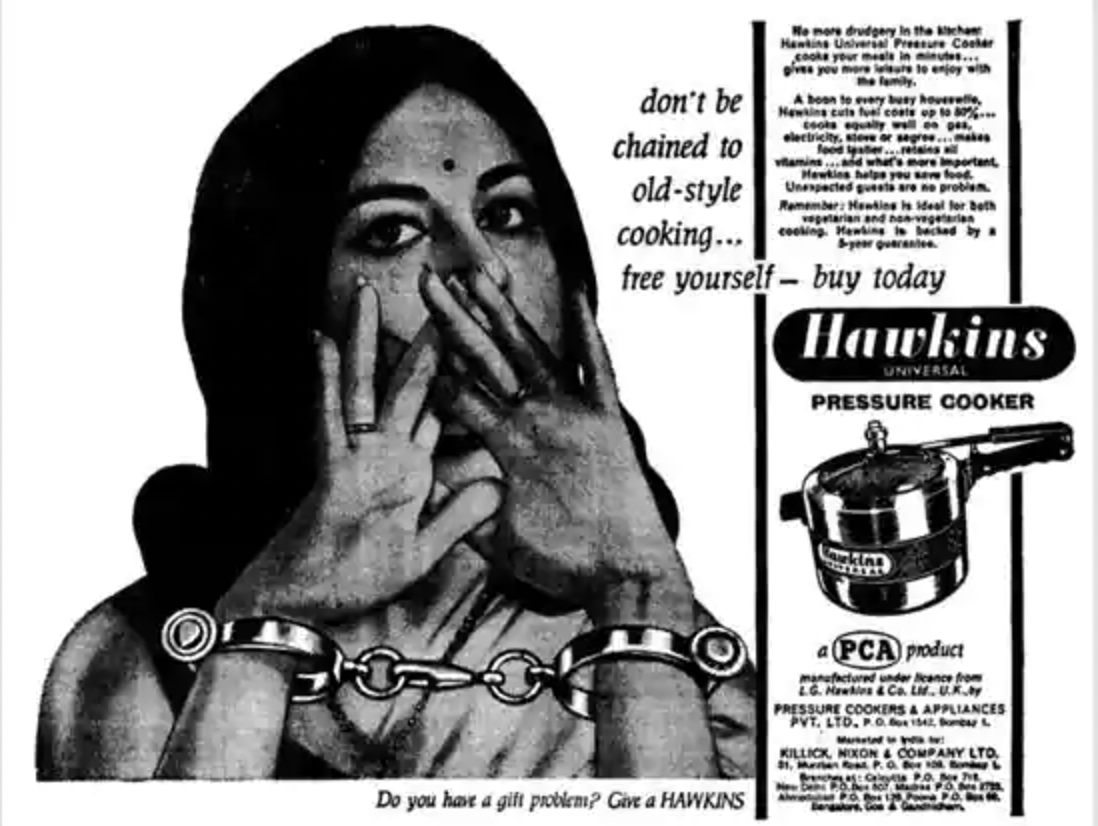

While the frenzy surrounding the Instant Pot largely focuses on newfangled innovation, there are overlaps between this technology and its ostensibly dated ancestor: the pressure cooker. A brief overview of pressure cooker advertising, for example, shows us how the language of advertising for the two technologies, though decades apart, is strikingly similar. In these ads, efficiency of labor and the resulting increase in leisure time is always touted as the main benefit. For example, in a 1980s Hawkins ads, women who are assumedly sister-in-laws share the time-saving secrets of pressure cookers with each other in culinary solidarity. In another, a benevolent mother-in-law signals her hard-earned approval for her daughter-in-law by revealing what can be done with the gleaming Hawkins or the Prestige, designed to release real and metaphorical steam. “Creates the extra leisure you need”, promises one vintage Prestige product print ad, which depicts a woman not yet privy to the wonders of the pressure cooker as “chained to the kitchen”, while her tech-inducted counterpart is shown to have “more time for useful work”4. Through the decades, women in these ads appear to have internalized the pressures of labor; the ideal woman emerges as docile, attractive, and not only capable of doing round the clock back-breaking work, but delighted to be doing it too.

Despite the problematic gender norms perpetuated by pressure cooker advertising, the imagery is always sociable and communal. The gendered body is always shown to be living with others, feeding many mouths and negotiating a life of complex kinship. This portrayal is in contrast with that of the Pot, which, in ads and Youtube reviews, imagine the solo woman as the appliance’s target audience. While time-saving is privileged, it is through the schema of individualized labor, and for a woman who is busy with other things outside of the kitchen.

- 4. The same ad also problematically states that even a twelve-year-old girl can use the technology.

The argument for more leisure time for women is, of course, welcome in any context. But what gets occluded in this simplified discourse is a neo-colonial assumption: like the pressure cooker, technology brings innovation, and innovation opens up the possibility of free time for the primary cook. However, such designs for a better life are predicated on the premise that the cook is assumed to be cooking alone, and desperate for a certain type of leisure, one that is often pre-packaged for her as a capitalist consumer.

This raises some questions in the Indian context. What happens when cooking for the home is a full-time profession? What happens when the kitchen is shared by multiple people, many of whose livelihoods depend on perfodrming manual culinary tasks? And finally, what is at stake when sociality and innovation are themselves realized through the collective performance of traditional culinary labor?

While time-saving is privileged, the Instant Pot is marketed through the schema of individualized labor, and for a woman who is busy with other things outside of the kitchen.

The tension surrounding the Pot was laid bare for me at a dinner I was recently invited to. My friend Priya was excited to use the new technology, and promised me that she could make cocktails while “the Pot was doing the dirty work.” Her home was one where I have dined many times, and enjoyed the excellent food she and her staff jointly prepare. But this dinner was different: in the middle of the kitchen was a shiny new outsider, one I jokingly remarked seemed like a distant American cousin we had just met; Priya laughed, as we collectively recalled the familiar, mixed whiff of wariness and curiosity NRI’s (Non Resident Indians) would historically carry.

While Priya pressed “sauté”—the first step of three in her Paneer Makhani recipe—she began telling me how much better her life has been since the Pot entered it. “More time to chill,” was her declaration of liberation, but most of all, she said, the tech allowed her to produce the same flavors as the much romanticized “haat ka khaana” (literally, handmade food) that most domestic gendered bodies are simultaneously celebrated for, if not enslaved by. The love for “haat ka khaana,” is most often expressed by men. Though often used as a genuine appreciation for the cook’s talent, it is tokenizing when you add up the many hours of culinary labor that go into achieving the ephemeral feeling. In counting its additional benefits— like safety and silence—Priya expressed that she was “sold” on the Pot, but had to maintain her classic Hawkins cooker because her “staff refuse to accommodate.”

While I was intrigued by Priya’s summary of her staff’s sentiments, I suspected it was not the whole story. I asked them about their relationship to the technology in private. While they expressed a novel intrigue, they were skeptical. The Pot required a stable electricity supply, which they never felt they could count on. The silence was a source of suspicion, and made them question the food’s “doneness”: a state that is usually determined via a combination of tactile, visual, and gustatory senses. But most of all, the main cook, Kishan, did not share Priya’s conclusion that “haat ka khaana” flavors were being replicated; for him, this was only possible by “bhunoing” (rigorously sautéing) the masalas and vegetables over an open flame. Moreover, while Kishan did not make a direct case for his expertise, I understood from our conversation that he did not believe technology could ever take the place of a seasoned cook’s hand. This was also, possibly, a way of saying that his labor, and the labor of the other staff were not dispensable.

I was curious about whether Kishan cared about saving time, and whether using the Pot could free up his day to do other things, or even work in multiple homes. His response pushed me to question the neo-colonial assumptions often embedded in arguments for modern technology. “All life is work. “Free time has no arrival or departure date, it comes, and it goes,” he said.5

His poetic response was revealing. It told me that for someone like Kishan, who like many domestic workers in India work between 12-16 hours a day, “saving time” was an unthinkable privilege. Free time, when it “came and went” was not a quantifiable thing. It was, for sure, at odds with the gleaming digits on the Pot, that happily beeped to tell Priya she could come back to the kitchen, inadvertently interrupting our conversation.

Her paneer makhani was ready.

- 5. This is a translation.