With New Year’s celebrations behind us and Valentine’s Day just a few weeks away, we thought we’d focus our first column in the Drinking by Design series on a sound we have recently heard quite often: the pop of a champagne bottle as it is uncorked. It’s a festive, spontaneous sound that actually represents several hundred years of innovation.

On Bubbles

The design of the pop begins, of course, with the bubbles that give champagne its celebratory nature. Winemakers in France first noted this effervescence at the end of the fifteenth century, when unusually cold winters halted the fermentation process in the fall. A second fermentation began in the spring, when the wine was already stored in containers, causing a build-up of carbon dioxide that created bubbles. For centuries, this was considered a defect, and efforts were made to eliminate the effervescence.

The English, however, were huge consumers of wine, and they developed a taste for these bubbles, beginning in the seventeenth century with the decadent and fun-loving court of Charles II. They even started created bubbles on purpose: in a 1662 paper, English scientist Christopher Merret noted the practice of adding sugar to wine to induce the second fermentation. In the early eighteenth century, the French court of Phillipe d’Orléans, nephew of Louis XIV, began drinking bubbly wine, and the French winemakers finally reversed their stance.

The Truth of Dom Pérignon’s Cork

Now the problem was how to keep the bubbles in the bottle, and the stopper from coming off. French monk Dom Pérignon has often been given credit for innovating the use of cork, tied off with string, for this purpose. Though he was certainly responsible for a number of improvements in winemaking during his tenure as cellar master at the Benedictine abbey at the end of the seventeenth century, both cork and string were in use much earlier in wine storage. Cork bark had been used as a bottle stopper in Roman times, and became popular again around the end of the sixteenth century. In the 1630s, the English courtier Sir Kenelm Digby developed a sturdy glass bottle with a “string rim,” that allowed you to tie twine over the bottle to keep the cork in place.

Champagne workers had to wear facemasks to protect themselves against exploding glass bottles.

Dom Pérignon was, however, responsible for developing a more efficient and hermetic cork. While this kept the bubbles from leaking out, the resulting build-up of pressure in champagne bottles made excursions to the champagne storage dangerous. Champagne workers reportedly had to wear facemasks to protect themselves against exploding glass bottles.

Marketing the Pop!

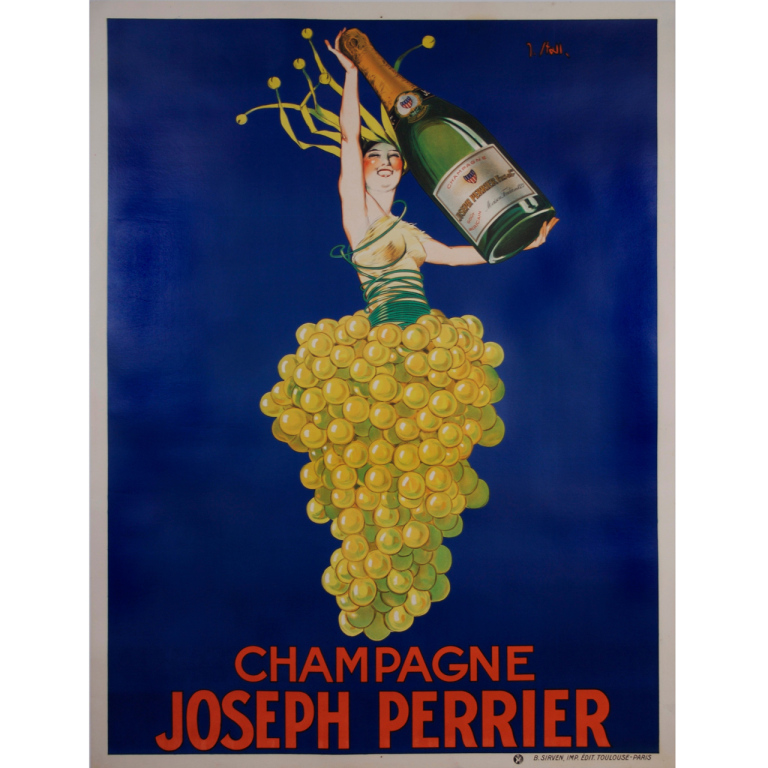

Throughout the eighteenth century, champagne increased in popularity, becoming the drink of royalty across Europe, largely because of the marketing efforts of the great champagne houses such as Ruinart (established 1729), Taittinger (1734), Moet (1743) and Veuve Cliquot (1772). Veuve Cliquot, under the guidance of the window (in French “veuve”) of the founder’s son, became particularly important during the nineteenth century for innovations in champagne production.

But the house of Jacquesson & Fils (founded 1798) was responsible for a final development in the design of the champagne pop. In 1844, Adolphe Jacquesson invented the muselet, or champagne cage, which held the cork onto the bottle securely with steel wire. Finally merrymakers everywhere could celebrate without fear of getting a cork in their eye.

So the next time you open a bottle of bubbly, raise a toast to the many people, from princes to monks, who gave that bottle its pop.