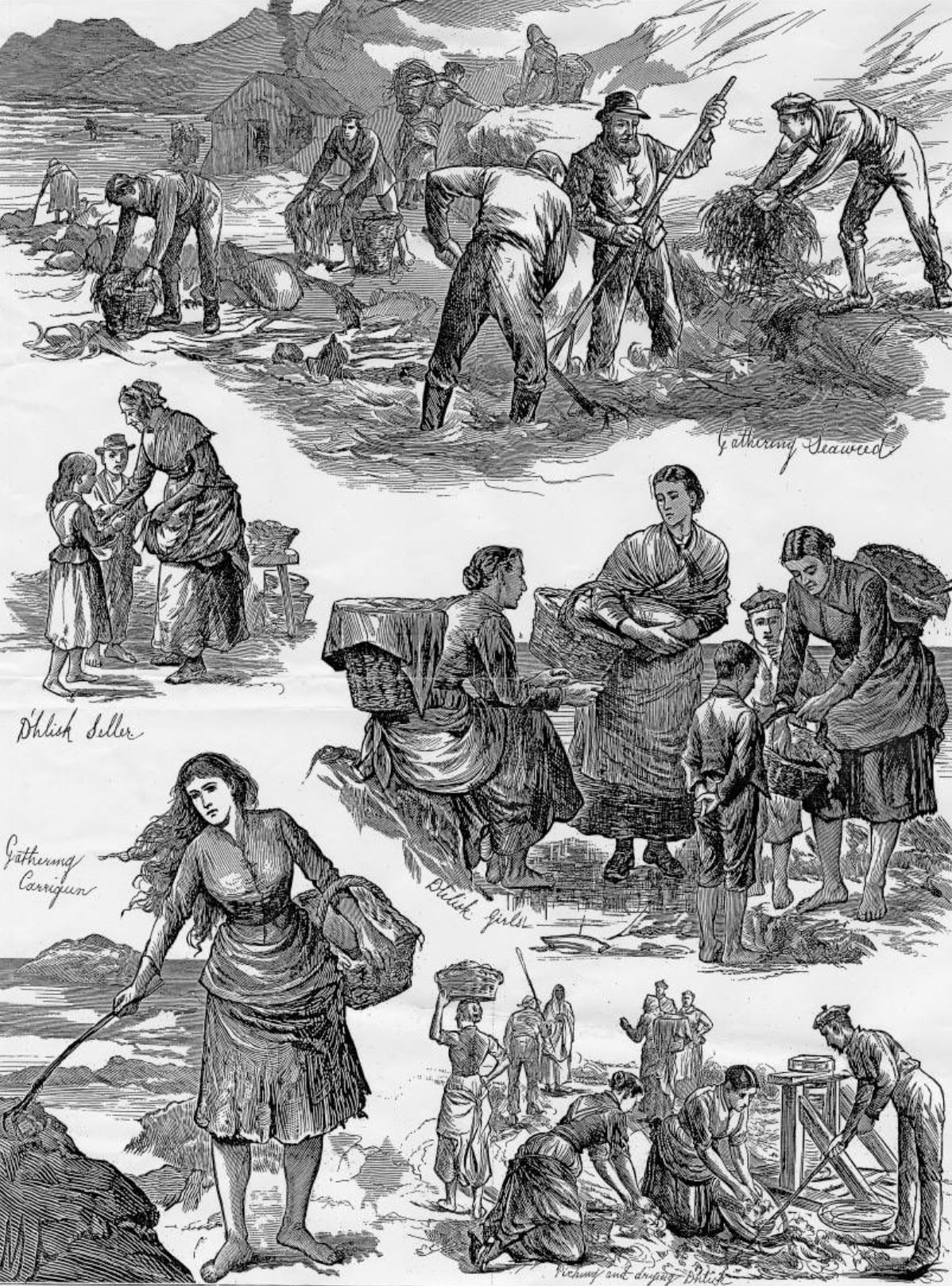

Recently, there’s been a lot of chatter about the nutritional benefits and sustainable possibilities of seaweed. Here’s a roundup of some projects that are jumping into the wide ocean of opportunity of underwater plants. But first, some seaweed facts:

Kelp vs. Seaweed

Seaweed is a broad name for marine algae (note, despite its name, seaweed is not a plant). Kelp is a subset of seaweed—a brown algae that grows in underwater forests. Most of the seaweed we consume is actually kelp, including Japanese kombu, seaweed salad and alginate (a thickener used in ice cream). We also eat red algae in the form of nori and Irish moss.

Seaweed drying for the Terroir project (below). Photo by Emil Thomsen Schmidt.

Seaweed drying for the Terroir project (below). Photo by Emil Thomsen Schmidt.

Nutritional Benefits

Seaweed is a decent source of vitamins A and C and some varieties can contain more protein than soybeans and more calcium than milk. It’s also a great source for iodine—a gram provides your daily recommended intake.

Because they require no fresh water, no deforestation, and no fertilizer—all significant downsides to land-based farming—these ocean farms promise to be more sustainable than even the most environmentally-sensitive traditional farms.

Ocean Farming

In 2011, The Atlantic published a great look at the state of ocean farming as a way to mediate climate change. Although there have been some start-ups, including this Kickstarter expansion project from Long Island-based Thimble Island Oysters, there are few large-scale seaweed farms in the United States. With the good news that came in at the end of 2014 that shellfishermen and seaweed farmers are now eligible for U.S. Aid, and the government itself promoting seaweed farming, the space seems ripe for expansion. Want to start your own seaweed farm? Consult the UN’s Food and Agriculture handbook.

Now that you have the basics down, here’s a deep dive on the history of the “kale of the sea” on Edible Geography’s podcast, Gastropod. In this episode, the team visits Dr. Charles Yarish’s lab at the University of Connecticut to learn more about the science behind seaweed farms, explores seaweed as a “superfood,” and cooks seaweed-centric recipes with chef Elaine Cwynar.

An Isreali-startup has created a countertop farming kit to grow and process a type of seaweed called khai-nam or duckweed, most commonly consumed in Southeast Asia. Inspired by 3D printing, the GreenOnyx grows and liquifies fresh duckweed at a push of a button, allowing consumers to get the benefits of the nutrient-rich algae without the hassle of processing it.

Terroir, or the land and environmental conditions that produce a flavor profile in produce and food, has long been an obsession of oenophiles. Increasingly, the term has been adopted by farm-to-tablers, locavores and foragers, to describe everything from coffee to cheese, pork to tomatoes. Designers Jonas Edvard and Nikolaj Steenfatt have designed a collection of seaweed and paper-based furniture and lighting under the name Terroir as a sort of exploration in local materials.

The material uses a combination of seaweed harvested along the Danish coast and recycled paper to create a tough and durable material. As the designers describe, the material is, “a warm and tactile surface with the softness of cork and the lightness of paper, which can be used for products and furniture. The color of the material is determined by the different species of seaweed—ranging from dark brown to light green.”

The seaweed is dried and ground into a powder and cooked into glue—utilizing the same thickening properties of alginate that food scientists and ice cream lovers enjoy. The resulting viscous paste is then molded into forms for lighting pendants and seating. See the process of creating the collection below. All photos by Emil Thomsen Schmidt, courtesy of Terroir.