This interview is part of our editorial series, Work in Progress on design and restaurant labor.

Telly Justice and Camille Lindsley are partners in life, business, and most importantly camp. The duo’s most anticipated collaboration is HAGS, a “restaurant for queers, by queers.” While Telly and Camille have been collaborators for over six years, HAGS will be their first (mostly) permanent installation where their combined creative histories in food and beverage will expand in a space dedicated to nostalgia, futurity, and play. The couple, along with an eager team that I have the pleasure of being a member of, are excited to invite you into a world building mapped by relational investment and community preservation. HAGS is a “fun attack” on the status quos of traditional fine dining, and a recasting of normativity as perversion. With a slated June opening HAGS will soon actualize as an alchemical primogenitor of an era of careful, inclusive, and shapeshifting restaurants to come.

Lo Alalay:

Describe the perfect meal.

Telly Justice:

My fondest food memories are potlucks. They were so informative to my finding of myself in community. The perfect potluck meal is shared among a mix of strangers, close friends, chosen family – everybody oftentimes brings a representation of themselves, often surprises – I love surprises – and a mixture of skill levels. The best meals for me are ones that are less focused on place or cuisine style, but more so the circumstances and the moment.

Camille Lindsley:

Often, my biggest source of ire with meals is the aspect of choice. I hate choice. If I could take a month off of choosing what to eat; I would be so happy. A perfect meal for me is one I don’t have to make a decision about. The perfect meal for me would be something surprising or chosen for me.

LA:

HAGS plans to feature a tasting menu. Why a tasting menu? Describe your relationship to a tasting menu.

TJ:

The oppositionality of not getting to choose from an a la carte menu is embedded in this trust dynamic with the people who cook our food. When it’s someone that you love and trust you’re more comfortable with leaving it in their hands. As chefs, we’ve totally disrupted the trust relationship in restaurants by taking the attention away from what the diners’ needs are to making it about us [chefs] and our artistic expression. Food can be seen through an artistic lens, but the work that we do is a larger diorama of many functioning parts, and building and honoring a trust relationship is a part of that art.

CL:

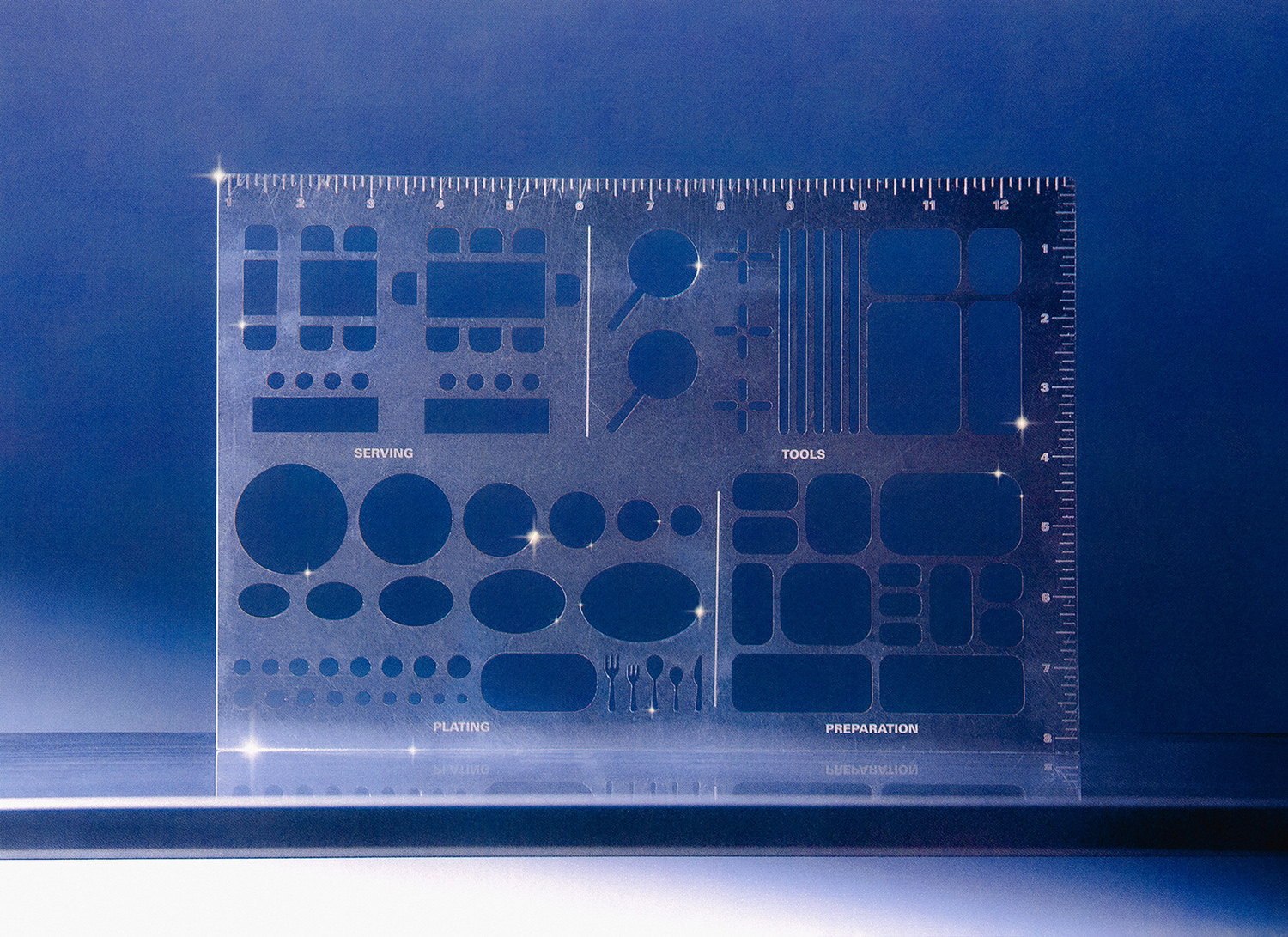

It also cuts down on food waste in an incredible way because you know how many reservations you have in the books every night, and there are x many vegans and x many omnivores you know exactly how many of each menu to prepare. You have a crystal ball into what the night will look like in terms of volume and determining what you need to do for prep. Whereas, for a la carte dining, there is a whole amount of chaos involved that is unpredictable.

There is definitely such a thing as too much chaos in a restaurant, and you are at the mercy of the guests and their whims.

LA:

A tasting menu as potluck!

TJ:

Yeah! You don’t make demands of the host, you show up and are fed what is prepared. And not in an egotistical way, but in a caring way. I totally get why there is a scrutiny toward our tasting menu concept. I think a lot of people might have us pigeonholed into this eurocentric space of the experience being the “chef’s artistic expression.” We really agonized in the very beginning about whether we would call it a tasting menu at all. There’s this pretentiousness of when you try to rename something that already has a name. Liberals and leftists have this bad habit of changing the word but not the praxis. We are focusing more on changing the praxis and letting the word stay.

LA:

What are some things you consider when feeding someone?

TJ:

We’re starting with a “five-course” [menu], in heavy quotation marks. We want to make sure we are not taking up three hours of someone’s night, but we also don’t want it to be so brief that people are in and out. Taking too much time can be unreflective about the way people live. Five courses feels like a good amount of time, and the right amount of food to feel well fed without the portion sizes becoming miniscule. I want the plates to feel full. I want them to know from the first course that they’re going to be taken care of, that they are going to leave full and the plating and plate sizes are not representative of their fears of fine dining. I like to imagine that a lot of people that come to HAGS will be having their first “fine-dining” experience, so there is a great responsibility in assuaging people from their fears and hesitations of what a night of fine dining can look like.

CL:

There is a level of deservedness of the reputation of fine dining menus being small portions accompanied by copious amounts of alcohol that can leave you feeling sick at the end of a meal. It’s honestly a pretty tricky balance in making sure people are fed enough, but not over feeding people

LA:

And how does the format of tasting menu benefit the labor structure of HAGS?

TJ:

Since the space is really small, it limits the amount of laboring bodies that fit in HAGS comfortably. Which has an innate relationship to the amount of labor that feels executable and in our control as professionals. I believe that tasting menu concepts really put a fine point on the daily structure of the work. There is no over exertion.

CL:

Restaurants are always in some sort of struggle with chaos and trying to be as consistent as possible. And if you can’t be consistent then you sort of betray the trust and expectations of the guest and it creates a more difficult work environment to be in. One of the many reasons I wanted to do a tasting menu is that it certainly makes the labor more streamlined and optimizes the quality of work we can offer. More chaos and moving parts often requires more bodies and labor to help put out fires and solve problems that arise that are part and parcel to having a variable work environment.

LA:

What does sustainability mean to you?

TJ:

We have this shared history of being restaurant workers in the South, which has a very different internalization of sourcing than here in New York. We have a more personal and direct relationship to our farm contacts. When they had a bad year, they could dialogue with us in the kitchen, and we could help them in so many different ways like buying an entire crop, or buying them seeds for the next growing season. These are ways of sourcing in the South that I would love to inspire up here. These things are not really a part of the conversation in Manhattan dining in my experience. We want to get to a point where we are working with our farmers like how I was working with farmers in Atlanta. It’s a long con. There’s a lot of relationship building to invest in.

CL:

Sustainability is a provocative term because it can be interpreted in so many ways. In a beverage sense, my background in wine lies both in the conventional wine world and the natural wine world, and I feel frustrated by both. Both worlds have dogmas that are fiercely held but not examined. For the classic wine world it is an unquestioning adoption of traditional, classic, eurocentric, and often boring ideals. Whereas the natural wine world can place a lot of dogmas that seem driven by the same capitalist values of marketing – really driven by the product of wine rather than the espoused traits of natural wine making that center sustainability, low intervention etc etc. People are more concerned about whether there’s SO2 in a bottle over whether someone is using fair labor practices in their vineyards. Both sides of the wine world forget to see a forest for its trees. Wine is first and foremost an agricultural product. My philosophy is centered around if the winemaker is a good steward of the land. In many ways these generations old, classic winemaking families have interests of sustainability more a part of their practices than a “new jack” natural winemaker because they have this long history and investment in making sure their vineyards can stay in their families for the next ten generations and beyond.

TJ:

Our vision of sustainable sourcing practices is more relationship based and with the individuals working the land and the land itself than it is based on a dogma of right and wrong.

The highest luxury is being included

LA:

When did you know it was the right time to partner in business?

TJ:

Before we started dating. I know we’re such weirdos.

CL:

We tried so hard not to date right away because we were coming out of some pretty nasty breakups respectively. We were hanging out smoking one night and we were like we should open up a haunted bed and breakfast in Savannah.

I can’t tell you how many schemes that we’ve come up with together.

TJ:

At this point [in knowing one another] we were attempting to build a surrogate for a romantic relationship. From the beginning we were working at the same restaurant together and we were both very jaded about the work. We weren’t being treated very well. We were talking a lot, being creative together, and also radicalizing over labor stuff. And all of it came together. So HAGS has been a very long slow planning process over the entire 6 and a half years we’ve been together.

LA:

What does it mean to own space and activate it?

TJ:

We have complex feelings about ownership. In a way we are just leasing space. We don’t actually own the space. We own the concept of HAGS.

CL:

I don’t believe in intellectual property.

TJ:

I hope people steal everything about HAGS. If I see HAGS open next door to HAGS, I would bring them a cake. IDGAF. Our personal relationship to intellectual property and the intellectual property of HAGS is that: we don’t care. It’s not something that we want to hoard.

CL:

None of the ideas we’ve had are original. I mean, Pay-What-You-Can Sundays is our homage to Food Not Bombs, Free Breakfast for School Children, soup kitchens, and Queer Soup Night. People have been doing pay-what-you-can forever.

TJ:

We’re not even the 100th people to think of this. Even the name HAGS is from this yearbook culture thing, is pop cultural canon. There’s nothing about HAGS that I feel like we own, and we’d certainly never hoard it or call people out for “stealing” an idea.

Opening and building queer space is an act of preservation of community especially as I see rainbow capitalism take root and queers losing a sense of place, identity, and radicalness. I’ve seen so many places disappear over my years and not be replaced. We have to do the work of having space for us or we will lose everything that is important to this community.

CL:

It makes me sad that fine dining is starting to die a little bit. I want fine dining to have a place in our lives and to prove to people that it doesn’t have to be some classist vestige. There are so many different ways that you can have a fine dining experience.

TJ:

There’s this trap door in radical politics that says, “If I don’t value it then you shouldn’t either,” and there is a homogenization of priorities and a homogenization of the luxuries that are right and wrong to indulge in, which is not reflective of how vast and diverse and multi-talented this community is. I would love to see indulgence shared for other priorities and cultural practices akin to the way that individuals value nightlife, concert-going, theater, and hopefully fine foods too.

CL:

It’s really easy to inflate status symbols and associate them to class, and they’re not the same thing.

One of the many reasons I wanted to do a tasting menu is that it makes the labor more streamlined and optimizes the quality of work we can offer

LA:

How do you plan on cultivating space without the connotations and formalities of fine dining?

CL:

When you are in a space, there are lots of cues. There are lots of little things that can make people feel their needs have been anticipated in a way that doesn’t make them feel like they’re in a stuffy environment.

TJ:

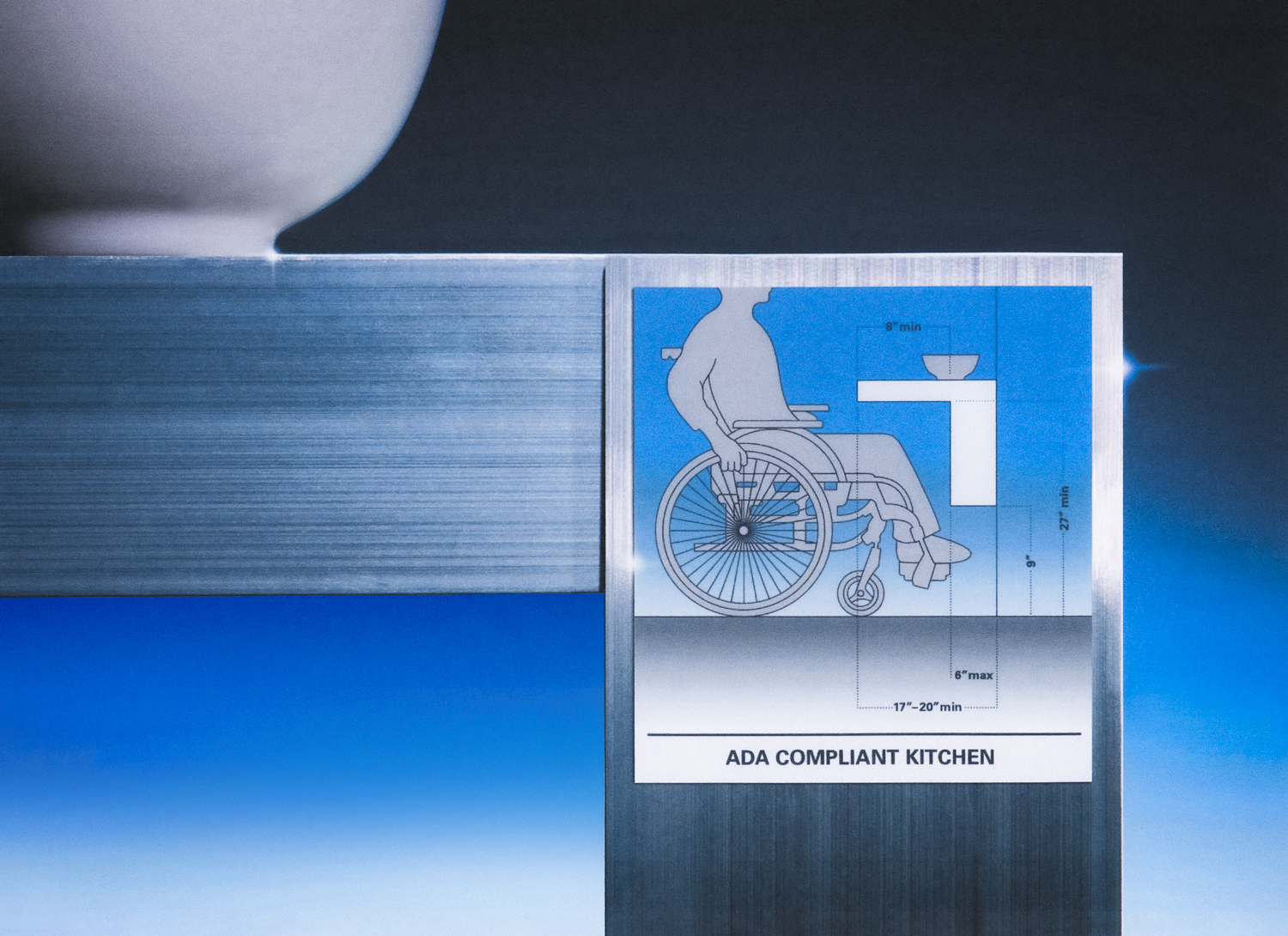

I see it from how space is going to be interpreted by the diner and how space is going to be interpreted by the staff, and can we convey the space as a space of comfort, luxury, and inclusivity. The highest luxury is being included. This comes from my lived experience of always feeling incidental to the scene. Having things like pronoun pins available immediately alleviates pressure of self-advocating. We recently had someone attempt to make a reservation for their recently out teen. Imagine being that teen and feeling anxious about what HAGS is going to be, and you’re offered this opportunity to choose your pronoun, and have the awareness built from the moment that you walk in that you are going to be respected in this space as you are. We are inviting people that aren’t often invited. The front door is very visibly ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) compliant, the playlist is full of queer canon from all generations, the bathroom is stocked with comfort products, narcan, and sharps containers. There are things that we have to do that communicate that it is as inclusive of a space as we say it is.

LA:

Why the East Village?

CL:

We looked at a lot of different neighborhoods. None of them made sense. We looked at a space in Park Slope and we were like why are we here? We could not have considered a worse neighborhood. We also looked at places in the West Village and it also was not for us. Imagine HAGS not in the East Village…. and it begins to make a lot less sense. It’s a really interesting neighborhood too when you think about the restaurants that have come up out of the East Village. They tend to be restaurants that push boundaries and are very niche concepts. Also, there is a big history of radical activism in Tompkins Square and the neighborhood surrounding it. The more that we thought about it, we had to open in the East Village. We feel really lucky to be a part of the culinary heritage of the East Village.

TJ:

It’s very important for folks that are owning and operating businesses to do it in the communities that they live in. There should be a finger on the pulse of what the relationship of the place to the community is, and what it does both positively and negatively to the neighborhood. You have to respond to the community’s needs as they emerge because they are changing all the time. Living in the Lower East Side made it very important for us to invest in a space in the East Village. We are not the right people to open a business in Brooklyn, and I have no interest in inserting myself into a community where I can open a quick cheap business. We want to come in and support and integrate within the community from the inside rather than marketing to a community or off of a community. There is extraction like this in most central Brooklyn neighborhoods. I want to be in the East Village because the community is supportive of us and we want to be supportive of it.

LA:

What does veganism mean to HAGS?

CL:

So we are both ex-vegans. We’ve got 10 years of veganism between the two of us.. Becoming vegan used to be a political decision. I stopped being vegan because I realized I was a hedonist. It was this radical moment for me because I had developed this political and radical relationship with food by going vegan. Then it became a radical act for me to break my veganism to eat what I want when I want after considering the ways that femmes are often policed about how and what they put into their bodies. Having this very political tie to food really heightens the meaning of sharing that food in space with people that also think about food in a similar vein.

TJ:

My first relationship to radicalizing in any political sense was leaving home for the first time. Having no experience with taking care of myself, I was embraced by this very radical and queer group of people who showed me how to treat myself well through body practices and veganism. There was this center of anti-capitalism, anti-racism, and animal liberation. For these punk, queer, anarchist communities back then, we bought in to multiple praxis, and veganism was one of them. We believed in sentience and how special a life is. I still believe a lot of those things, but I internalize them a lot differently now. I started to drift from these beliefs in different ways as I started to understand and adopt a labor politic and an understanding of the relationship generational farmers have to the land, animal rearing, and slaughtering and realized these were important cultural practices to these families. I have a very personal relationship with food and farms that synthesizes potlucks, veganism, being queer, building community, and seeing a world that is larger than myself and participating in it. It’s this weird blended soup where no element can extract itself from the soup.