Pre-order your copy of SEEDS, MOLD Magazine Issue 05 here for a pre-order price of $18USD. Expected ship date is March 22.

With the COVID-19 outbreak in New York City, we were alarmed by the seismic effect the quarantine had on our already food insecure city. The pandemic amplified systemic inequities in our current food supply chain and the failures of our globalized approach to feeding ourselves and our communities. Inspired by the rise of local mutual aid groups and the Little Free Library movement, MOLD commissioned seed libraries from our favorite New York designers and chefs with the hope that their approach might inspire others to freely share seeds and stories within their communities and beyond.

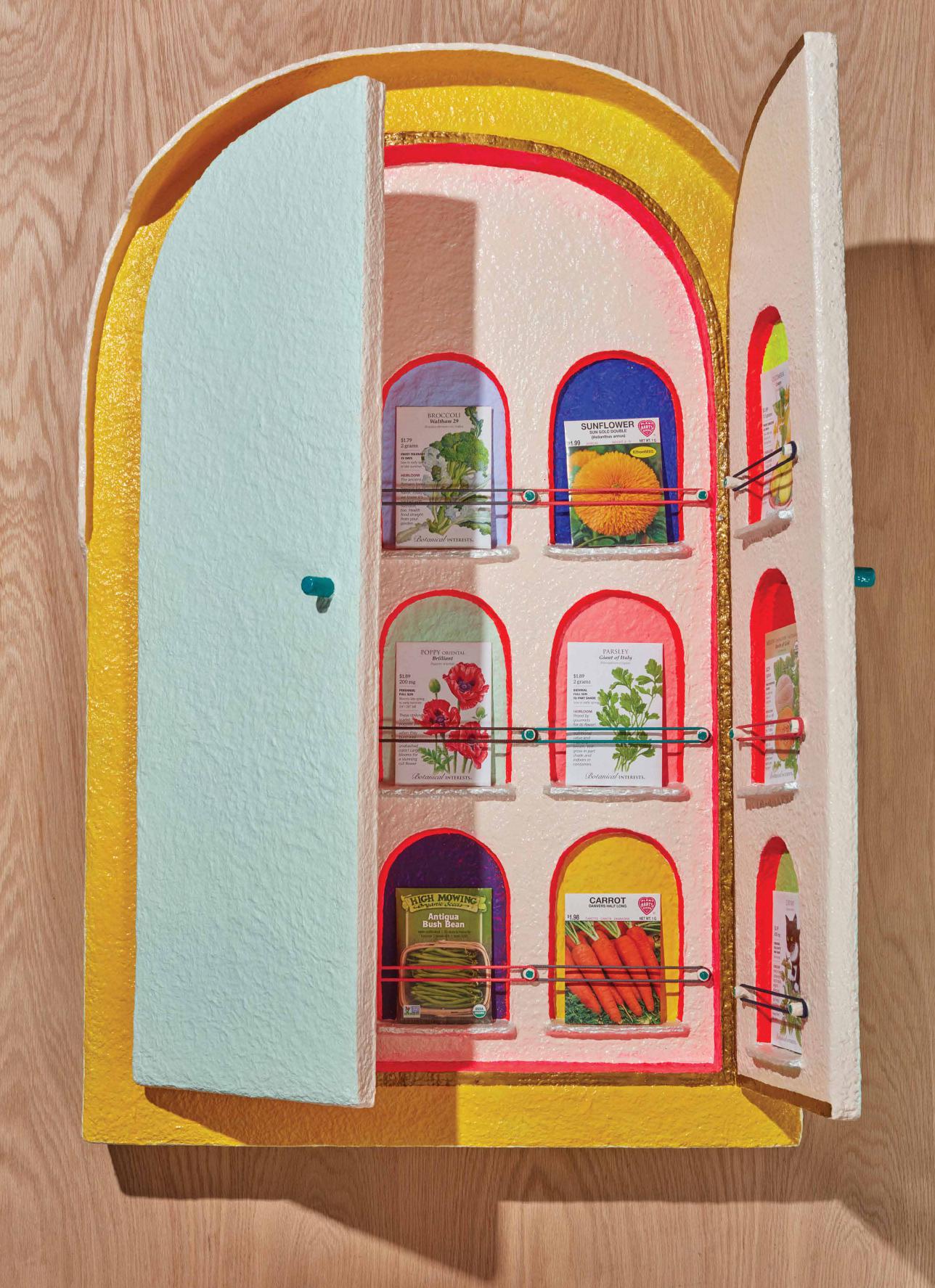

Artist statement by Chiaozza.

Photography by David Brandon Geeting

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic we decided to go to our friend’s family farm in Vermont. It’s an apple orchard on 300 acres of land with multiple units for living. When we first arrived it was scary as no one really knew how to manage the virus. We were all holed up on the farm like it was an isolation chamber. It was a surreal place to experience the early days of quarantine, but it was a nice place for our daughter Tove to get outside and run around and for us to experience a little bit of nature during a weird time.

Being on a farm, and an apple orchard specifically, at the end of winter/beginning of spring, there is the sense of life in the soil being part of the atmosphere around us. Then to be invited to think about seeds while in an environment of those trees felt like a really strong, poetic connection during the process. There was a little embroidered artwork on the orchard that said, “He plants a seed, the fruit of which he may not see.” It was a poetic reminder about the gift of work, the gift of toil, and the idea that we might not benefit directly from the things we do now. It was also about recognizing how much work goes into cultivating and providing food for the world and each other and how that work is so important to our survival.

This vibrancy is hope for magic, hope that the seed might lead to something even more than what it claims to do.

At the farm, we didn’t have many of our tools or materials with us. There was also a feeling of material scarcity, especially in the spring and early summer when we weren’t really going out to get things and many shops were not open. So we started our own little recycling plant in Vermont, saving and organizing everything that would generally get recycled or thrown away. Almost all paper products were saved—food and delivery boxes, toilet and paper towel rolls, and because it’s an old farm, we discovered these piles of huge, old Vermont phone books that became part of our material supply.

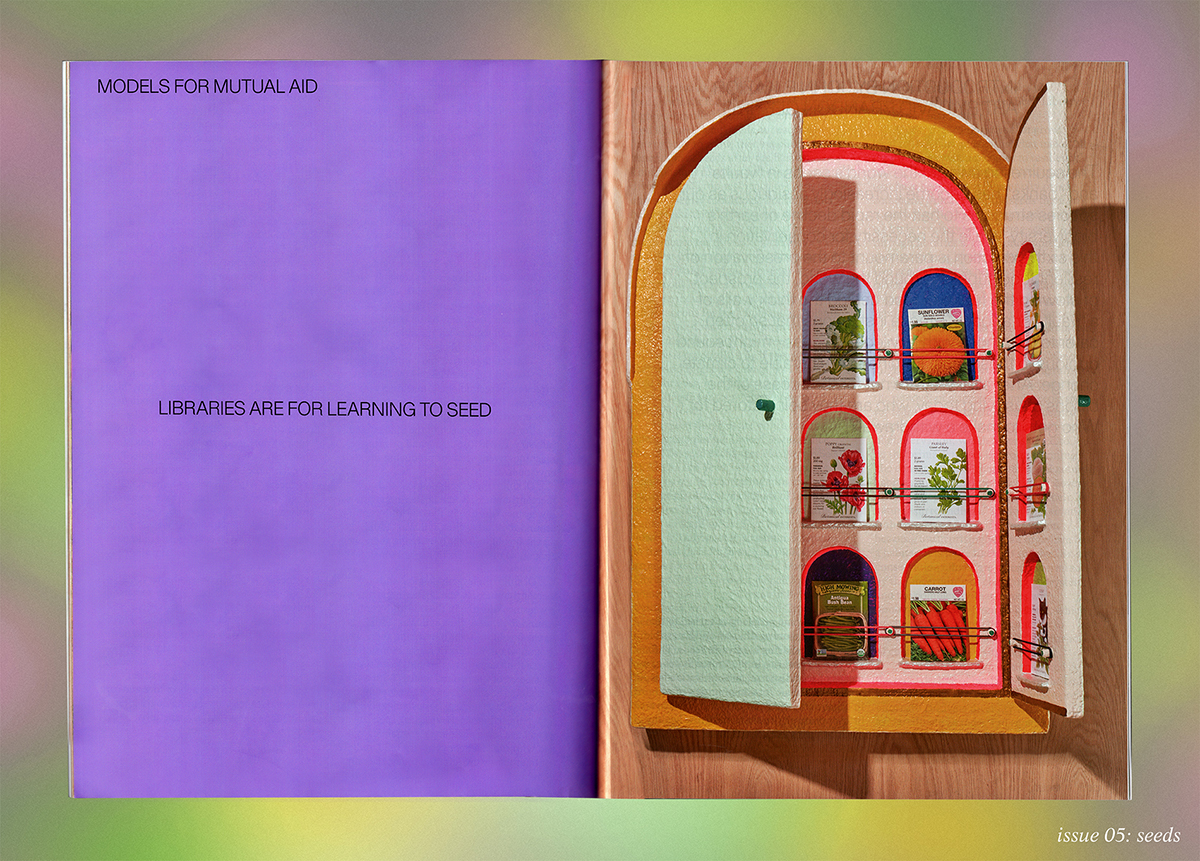

We’re used to having some tools and materials to fabricate and build things, and we were in this interesting place where we were really using what was around to build the seed library. It ended up being quite a large object—more than three feet in one direction, and the armature was pieced together using cardboard boxes, which was its own challenge because we discovered that there weren’t often boxes that large. Not to mention that cardboard is easily susceptible to the wet environment of the paper pulp process. The cardboard armature would start to bow, and trying to force something to become a solid, rigid object was an interesting challenge. We learned that we could use packing tape as a resist. So every time we had a panel built for the armature with cardboard, we covered the cardboard with packing tape to kind of prevent it from getting all soggy and wet with the paper pulp. The level of construction was like making furniture with trash.

We made all the paper pulp for the seed library out of recycled phonebook pages. It took a lot of time—Adam would be pulping while all of us were watching a show or reading a book, pulping during Zoom taco nights with friends. It was a lot of work. It seemed like we worked on the Seed Library for a month, anytime we weren’t doing something else like taking walks by the river or doing activities with Tove.

The form started with these great drawings of architectural structures that we thought of as houses or huts. Some designs looked like archives, files or card catalogues. We thought about the times we’ve approached a Little Free Library on the street—there’s one on the corner of our studio building—and there’s often a little door for what looks like a house. Over time and with use, these little libraries and even a catalog might start getting messy, or things might start getting lost inside. You can’t necessarily see everything at once.

We liked being able to see most of what’s in there all at once and encourage a neat treatment where it’s not just throwing a seed packet in, grabbing one back and then going. We wanted a thoughtful, considerate touch and a place for trade. We also liked the arch shape that was showing up in some of the sketches. Then we got onto this idea of a “seed sanctuary” and thinking of it as a sacred space for seeds—each seed packet would have its own little archway, almost like votives in a Catholic church.

We were also trying to be thoughtful about where the seed library could go and how it would need to be outside, so somewhat weatherproof. Our seed library has a little cap bill and the seed packets are inset a little. Each seed packet has its own archway and we used elastics to hold each packet in place. We imagined it being a wall object. Instead of a poster it could be hung on a community bulletin board. There was a food co-op that we frequented in Vermont, and we were using their entryway as a model for where the seed library could go. They had a Little Free Library, a garden with a picnic table and a wall of community flyers that people would leave. We also liked the potential that it could be strapped to a tree or pole, but we didn’t end up pursuing that direction too much because of construction challenges.

We’ve been watching more and more things with Tove, and one of the things we all love watching is Pingu, a show about a little claymation penguin. There’s no language but there’s sound—a lot of chirping and flapping. The design of the interior spaces is so beautiful, minimal and playful. Some of those shapes, like the chairs and the cabinets on the wall, have this beautiful rounded arch. So as we were building the seed library, it was like we were building a Pingu furniture object.

We like the idea that the library might conceptually exist in a cartoon or fantasy world. Riffing off the idea of “Jack and the Beanstalk” magic seeds and the plant aspect of our work, there is also a hopefulness, a sort of unknown in planting a seed. The cartoon fantasy world of our art is permission for us to explore the ridiculousness of nature and how bizarre it can get. Although the exterior of the library is somewhat subdued—there’s a lemon-lime, sunbleached vibe going on the outside—when you open the library doors, you get a textured, bejeweled, vibrant interior. This vibrancy is hope for magic, hope that the seed might lead to something even more than what it claims to do. When you open the doors, it should feel like there’s a singing voice coming out!

Cartoons are also a beautiful expression of minimalism where they show just enough so you understand the picture of what’s going on, and they’re often restrained because you’re literally drawing thousands and thousands of things over and over again (like in cell animation) or moving whole objects around (like in claymation). Every object in the scene has significance—there’s nothing extra. The aesthetics of cartoons is inspiring because it’s a way of looking at what’s essential to get a narrative or a feeling across. The form and the colors, the shapes and the references are accessible, something that people can immediately connect with. It’s like an invitation. The seed library is about the curiosity of opening a door, peering through and discovering a little world inside.