Read more from In Service, our monthly look at the future of hospitality from innovators around the world.

When Indonesian entrepreneurs Ronald Akili and Jason Gunawan created Potato Head, they figured it a one-off restaurant project—hence the “joke” of a name. But with a serious talent for providing good times, they now have an array of hospitality projects spanning four cities across three countries in Asia, with more on the way. On a recent trip to Bali, we spent an hour chatting with Akili to learn more about drawing inspiration from the team behind their organization, Potato Head Family, the power of simplicity and where they’re headed in the future.

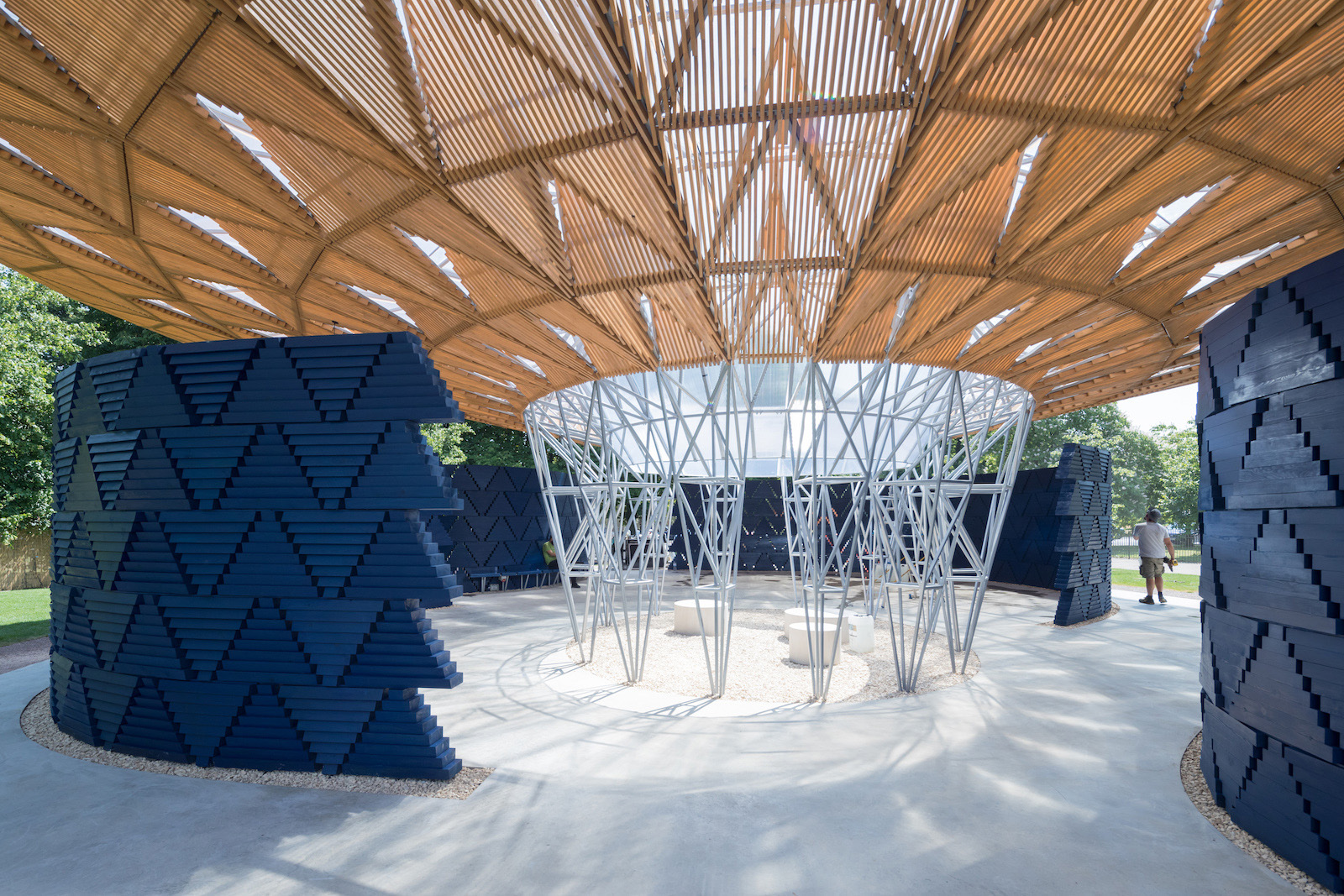

Outer envelope of Potato Head Bali

Outer envelope of Potato Head Bali

Karen Day: When did you start Potato Head Family?

Ronald Akili: We started with Potato Head—a restaurant and bar—in Jakarta in 2009. It was a coincidence actually. I was working for a real estate company and created my own housing project to showcase contemporary Indonesian architecture. Art has always been a passion as well, so I started a gallery with my partner now, Jason Gunawan. Then I met my wife, who was a chef that came back to Indonesia from London and wanted to open a restaurant. I called Jason and was like, “Let’s open up something with Sandra.” He was doing some F&B projects before, so when my wife came back we opened up Potato Head.

We started Potato Head based on what we like about design, food, music, art, fashion—all those things. That’s how we grew the company, as a lifestyle brand. When we expanded to Bali I knew we didn’t want to create just another restaurant so we did a master plan for the whole compound: create a beach club, get some industry recognition and make a name out of Potato Head. Back then, no one in the world was interested in anything out of Jakarta. Bali gave us that stepping stone for international recognition.

How many projects do you have now?

About 10 projects in total now, between restaurants and currently two hotel projects. We have projects in Jakarta, Bali, Singapore, Hong Kong, next year Melbourne and Los Aneles in 2019.

Potato Head bar and restaurant in Hong Kong.

Potato Head bar and restaurant in Hong Kong.

How many people work for Potato Head Family?

We have almost a thousand people. To help us foster our culture, this year we’re launching our own academy. We’ll dedicate 70% of the academy to training our internal team and 30% will work with external NGOs to empower people within our immediate surroundings by providing training and jobs in all of our establishments. We believe that unless we invest in fostering the culture it’s almost impossible for you to get that culture when you’re here. It’s easy to do in one restaurant or one hotel, when you’re there everyday with the team and you can eat together in a staff meal. But as you grow in different geographic locations with different cultures, we believe that a stronger effort, a more productive infrastructure is needed.

What are the first steps in your design process?

I think we’re very fortunate that we’re still privately controlled and can do things based on what we’re passionate about or based on the people that we meet; our friends, our communities, that’s how we initiate every idea. For example, I’ve always loved the Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto and when the Hong Kong project came up we thought he would be the perfect person for it. We have a local person in Hong Kong so it would not be a “Sou” project and it would not be a “Potato Head” project. It’s a combination of what our local partners are envisioning for the space, what we envision and what Sou envisions, and we collaborate based on that.

Inside and outside the four-storey Potato Head hospitality hub in a historic building in Singapore.

Inside and outside the four-storey Potato Head hospitality hub in a historic building in Singapore.

How do you describe Potato Head Family’s design ethos?

We always look at the old because we don’t believe in trends, we believe in timeless design that relates to our heritage. And that relates to our group—the people that run Potato Head, it’s like the United Nations. Every single project that we do, we brainstorm together based on all of our heritages and experiences and then take that local approach in specific directions and combine it. We try to do things as sustainably as possible, but not for the sake of LEED certification, we just want to do our part and help to our maximum potential. Every project that we do we try to help bring up the local community and sustain specific industries that are dying out. Our approach is always internal inspirations and old traditions that we interpret and put in a modern context.

What’s the process like for an internal brainstorm session?

We take expertise from many different industries and a lot of people that work on the team have never worked in hospitality. It allows us to have a fresh approach and the freedom that we don’t know any better! As we grow we bring in professionals from the industry, but people that can take what we have and assist that rather than change it. We have our own architecture and design team, creative team, a team that sources everything about artisans and craftsmanship. We’re adding another team that will focus on how we can make sustainable stuff that’s as modern as we are. We do a lot of R&D.

Before we built Katamama, we did a whole year of research about all of the materials found in Indonesian temples, old houses and funicular architecture. In terms of the hospitality of it, we have notes from our travels and things that we hate, like asking for ice all the time or depressing mini bars—like why don’t we just make that pleasant? Or the check-in process, why do we still have to check in? Why don’t we make peoples’ lives easier?

The newly opened Katamama boutique hotel in Bali. Potato Head Family used over 1.5 million hand-pressed Balinese bricks to create the structure.

The newly opened Katamama boutique hotel in Bali. Potato Head Family used over 1.5 million hand-pressed Balinese bricks to create the structure.

What is most important when designing any project?

We feel like we wouldn’t be able to create a space unless the soul is there and the soul can only be there by the people that are running it and by the community that’s surrounding that space. If you see our project in Hong Kong, we took a space that was still very raw and we chose a location that was up-and-coming rather than an established.

We still have mom-and-pop stores underneath our building and on top is still residential. We chose a pattern that was used on old shop houses, modernized it and covered the whole building with it. If you see it, it looks like the neighborhood, but once you go inside we have a lot of personalities. We brought in our Indonesian cuisine but worked with local chefs and purveyors, and we created a music program [for the listening space] but instead of running it based on us, it’s run by a music director based out of Hong Kong. We gather similar-minded people in one community and connect all those dots.

How do you define hospitality in your work?

Our mission in the group is to provide good times and good in the world. And we treat every establishment like our own houses. The way we were brought up in Indonesia is like, any guest that comes to our house, before they come we prepare our house: the best bottles, the best food. If you go to the most remote villages in Indonesia that’s the culture. Even people that are underprivileged would still provide tea for you. This is the philosophy we take as a company, hence why we put the name of family on the back just to remind us. Our mission is to make sure every single guest that steps inside our home will have a good time.

What is the most significant element that influences good times?

Good, genuine service. Service from the heart. Forget about the skillset, people will always forgive you if you serve people from the heart even if you don’t have the necessary skills. And good food and drinks. We make it as simple as possible, as comforting as possible, as relevant and delicious as possible, and then the chef and bar director get the best produce as possible and prepare it as simply as possible. The more simple it is, the more difficult, but that’s what we want. Make dishes that are nostalgic, dishes that you eat and feel like, “Wow!” Good design, good atmosphere—all the human senses. Good service, good food and drinks, make it welcoming, accessible, fun.

Rooftop bar at Potato Head Singapore

Rooftop bar at Potato Head Singapore

Does social media affect what you do?

I think it definitely impacts every single industry, you’d have to be a fool to say it doesn’t. Personally I don’t have any social media accounts, I’m an old-school guy. I turn off all my technology when I go on holidays or when I go home because it’s impossible to shut off otherwise. In business I encourage and embrace technology; if we don’t evolve accordingly there’s no way to survive. With social media we used to be able to touch 100 people and now we touch thousands, some that have never even been to our places or people that have been here, we’re still able to communicate with them. I think that’s the best thing.

Whose work inspires you?

There’s so much! I love what Roy Choi and Daniel Patterson did with Locol. For them to have the conviction to open in Watts and go into that kind of concept? It’s real and genuine. And then I love every single Oscar Niemeyer work, I look up to him as an architect. I love what Massimo Bottura did with his soup kitchen project. Will Goldfarb of Room 4 Dessert—he’s from New York and was quite a well known chef, worked with Ferran Adrià and all the big names but got cancer and had to stop and heal himself so he moved to Bali. I went there and it was such an amazing vibe. Back then it was just dessert but he always had a staff meal at the back of the restaurant so he would welcome [visitors] like, “Hey if you want to have a meal first why don’t you join our staff meal? Just donate whatever you want.” I was like, wow these are the type of people that inspire me.

How do you see the future of hospitality?

The reality is the world is changing in a way where people are much smarter, much more conscious, much more aware. It’s not easy to sell something that doesn’t have substance, and that substance can build a certain community of similar-minded people. It will create that authenticity, it will create that genuine feel and I believe this is why people are merging, people are buying one another out, the industry is getting disrupted, because people want something much more real. People want to be surrounded in a community that’s not based on loyalty programs. Like Sweetgreen is building a strong community, it’s just for one defined purpose and Whole Foods has a strong community for one defined purpose. That’s how hospitality can move on. I always believe hospitality is based on heart rather than technology. I believe in comfort, simplicity and soul.