In the exhibition Mushrooms: The Art, Design and Future of Fungi on now at Somerset House, curator Francesca Gavin explores the wild and wonderful world of these fruiting bodies and our multifaceted relationship with them through the work of 40 artists, designers and musicians. While imaginative minds like the artists Cy Twombly, Takashi Murakami and John Cage (read: psychedelic) satisfy a deeper understanding of the subject’s cultural context, the practical use of mushrooms—and how we can use them to better the environment—is a little more complex.

We asked architectural scientist and building technology researcher, Dr. Mae-ling Lokko, whose project “Hack the Root” features in the show, to dig in further. Here, she explains the basics, the benefits and the challenges of using mycelium as a construction material.

Mae-Ling Lokko’s mycelium panels are on view now at Somerset House. Photo by Mark Blower courtesy of Somerset House.

Mae-Ling Lokko’s mycelium panels are on view now at Somerset House. Photo by Mark Blower courtesy of Somerset House.

MOLD: What is mycelium technology, and how are you using it?

Mae-ling Lokko: Mycelium is the vegetative state of fungi that often gives rise to mushrooms. Underneath our forests or within the mass of organic substrates, they grow branch-like organisms in search of water and cellulose. They act as the most sophisticated form of nature’s glue, transporting, breaking down and feeding so many parts of our ecosystem. And in the materials I grow, parts of agricultural or food waste is fed to mycelium. Mycelia use it as food, consuming cellulose, water and other nutrients in the substrate mixture that enable it to grow into an insulation-type of material.

What properties allow it to have such a range of use?

The type of mycelium strain matter, as well as the composition of the agricultural waste byproduct itself. Typically I look at the percentage of lignin (structural stuff) to cellulose (sugar stuff) in the agricultural or food substrate and experimentally figure out the right ratio of substrate to give it the desired properties. I work with an amazing strain from our partners, Ecovative, whose main substrates are hemp, aspen chips of different sizes, and in the past, corn waste.

When I started working with mycelium years ago, we were trying to feed coconut-husk fibers and pith which have very high lignin content and relatively lower amounts of cellulose. One can imagine that hopefully you’d get a strong product because of all that lignin, but ultimately there wasn’t enough “food” for that mycelium strain to consistently grow successfully. So it’s a balance and I’m still learning a lot. Today, for growing wall-scale or small-building scale installations, we mainly add “additional nutrition” onto their proven substrates, but on a material scale we can be more experimental.

Carsten Holler’s Pilzkoffer (Mushroom Suitcase). Photo by Mark Blower courtesy of Somerset House.

Carsten Holler’s Pilzkoffer (Mushroom Suitcase). Photo by Mark Blower courtesy of Somerset House.

How does an architectural material sit within the scope of an art exhibition?

I think that it’s wonderful that the world of mushrooms has captured many people’s imaginations and held their attention across different fields for a long time and in different cultures. To me, it’s powerful that some of the biggest names in contemporary art like Murakami, Holler, Twombly, can be imagined in the same space as a new feedstock for buildings and design. Every time someone encounters this work, it’s always met with glee first, fascination next and then skepticism, ultimately. But if we can talk about mycelium and mycelium products with the same level of acceptance and patience as we would of other inorganics, I think there are a lot of revolutionary ideas in the material life cycle offered—waste from agriculture through mycelium as a transformation agent.

Sometimes you do an exhibition or event and the ripples fade away. But there are times that ripple leads to something new, and “Hack the Root” at RIBA-North [Royal Institute of British Architects’ hub in Liverpool] in 2018 was that type of project, from the wonderful RIBA-North team, the urban food hub Squash Nutrition, a wonderful green start-up FarmUrban, the film company CAVA right down to the schools that participated in the growing. In fact, the panels in the Somerset show are actually from The Life Science UTC High School in Liverpool who took the panels from the exhibition and carried on with growing more down in the school basement over months.

The British designer Tom Dixon has a mycelium-based chair in the show. What does it take to make a material strong enough for use in architecture versus furniture?

Any mycelium product needs a strain, a substrate, some moisture and a mold to grow in. His mold is one for a chair and mine is for a panel. There are ways to improve the mechanical strength of the final project and that is by adding mechanical pressure and heat, which is also where my work began. But even without heat and mechanical pressure, I continue to be fascinated by the subtleties in the growing process that give rise to stronger mycelium products—techniques of adding pressure and their timing, as well as drying processes can have surprising impacts.

The Golden Cube constructed at Renssalaer Polytechnic campus in Troy, New York.

The Golden Cube constructed at Renssalaer Polytechnic campus in Troy, New York.

What are some of the challenges in what you do? Why isn’t mycelium technology a more widespread concept?

The life cycle of mycelium-based building materials and products are compelling; they take renewable waste resources in the form of agricultural and food waste that are tied up with our population growth and in principle, during their growing phase, it is a low-energy, non-toxic production method to produce materials we need. However, the biggest challenges I have seen deal with two ends of the spectrum: the requirements associated with the production infrastructure demanded by biomaterials and the quality-control aspect we expect these materials to meet.

The storage infrastructure we need to produce mycelium, at least for the strains that are on the market, requires that we keep them alive but relatively dormant so this requires refrigeration at a set temperature. It also requires time—five to six days of growth which if we use today’s methods of production in centralized factories, it is hard to scale up and compete with the demand. This, to me, is why this type of material economy needs innovation in terms of distributed production and needs more grassroots levels of production and quality control. I think that there are many exciting fronts in this regard, there are new models of biomaterials companies like Krown Design in the Netherlands that sit in a mushroom factory and gather molds from designers all over the world and grow these materials. I believe this is just the start of another wave of energy into the business of these mycelium products.

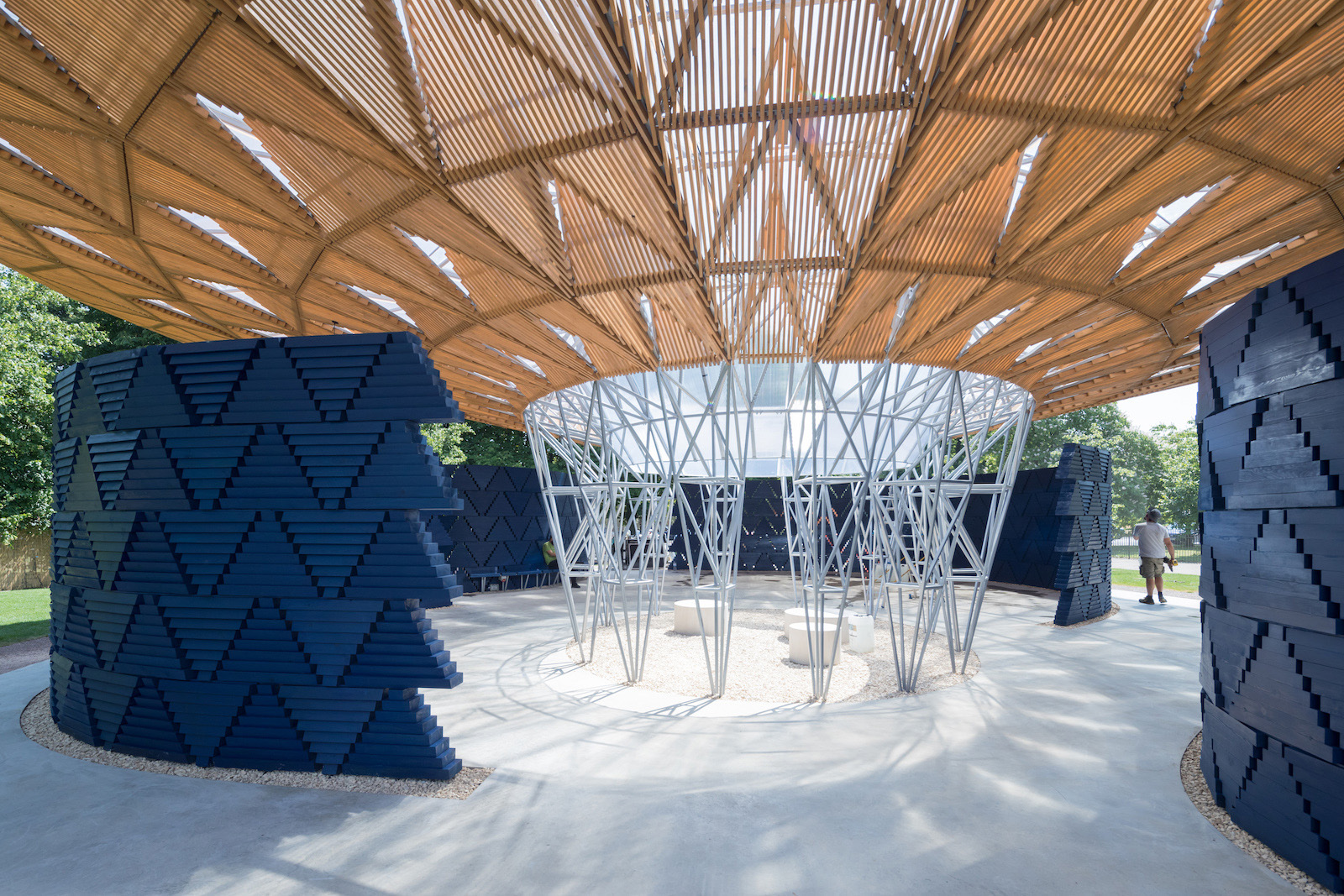

Chale Wote pavilion. Photo by Elaine Zhang.

Chale Wote pavilion. Photo by Elaine Zhang.

Is a deep understanding of the past the key to unlocking future methodologies, or how do these two interrelate in your work?

In trying to imagine new material life cycles and methods of production, I am indeed always looking to the past in terms of understanding the vast successes and considerable limitations of natural material technologies. Not so much in a nostalgic way but more of a forensic way. What were our expectations around maintenance, security, comfort, cultural identity and expression reflected in our buildings then? How is that different now? I have come to understand intimately the resistance to “biomaterial-based technologies” through the West African context, where the contemporary desire for future materials are tied up in deep economic, social and cultural paradigms.

You’re originally from Ghana. Is your work received differently there?

I think in America and in Europe there is a desirability for such materials as part of a more widespread, modern-eco consciousness; whereas in Accra, there are some aspects of that from a much smaller group. Often, it is seen as a form of luxury because it means access and the financial means to afford something “new” and “experimental.” But I do think appreciation cuts across class; the most engaged reaction I have had was with a carpenter in Accra during the Chale Wote contemporary arts festival in 2016, who started sketching ways of building a house with the agro-waste panels in a very pragmatic way. I think my motives are appreciated in both contexts the same, whether in Accra or upstate New York, where I live. Working with agro-waste is perceived as a form of economic empowerment and developing local capacity in a homegrown way.

What’s a discovery you have made recently within your work that has you excited about the future?

That there are mycelium strains from the Amazon that feed on plastic. And that vanilla is produced from beet waste-eating mycelia. I haven’t worked with either but the potential for beautiful smelling vanilla walls and my own plastic-biodegradation technology in my house sounds pretty exciting.

How can a normal person get involved in upcycling agro-waste or help move this industry forward?

Buy a grow-it-yourself kit from any mycelium producing company, use everyday objects in your home to grow something new. Ultimately upcycling is about having the patience to study the ordinary and re-envision how it could participate in the creation of something extraordinary.