This story is part of MOLD Magazine: Issue 03, Waste. Order your limited edition issue here.

I am an Italian chef. The most valuable lessons of the Italian kitchen are to make the most of nothing and to never throw anything away. No crumbs or bones ever get thrown in the bin. A ragù is nothing other than a sauce made with scraps of meat, fish or vegetables. In his Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well, Pellegrino Artusi collected recipes from all over Italy—North to South, islands included. We often say that, while Garibaldi was unifying Italy on the battlefield, Artusi was doing so in the kitchens. The recurrence of some ingredients is mesmerizing. Just think about bread. There are recipes for breadcrumb soups, loaves, meatballs, flans made with bread, not to mention the pasta-like passatelli. Even my favorite dinner meal, as a kid, was “milk soup.” You might wonder, so where’s the bread in that? Well, it was served with huge chunks of stale bread that I would dunk in a bowl of warm milk with a sip of coffee left from the moka machine added, and lots of sugar. I mean, loads. Delicious. Just like bread, meat can be re-cooked and re-purposed in many ways: meat used to make broth is then re-used in hundreds of other ways: meatloaves, meatballs or as stuffing for fresh pasta. And then there’s vegetables, cheese rinds and bones. What all these ingredients have in common is that they’re often considered leftovers. Bread becomes stale; meat has lost some of its succulent juices and flavor. But eventually, they are still used to make something nutritious and tasty.

A chef prepares dessert for dinner service at Gastromotiva. Photos of Gastromotiva by Angelo Dal Bo.

A chef prepares dessert for dinner service at Gastromotiva. Photos of Gastromotiva by Angelo Dal Bo.

Sylvie Fleurie is a contemporary artist who expresses her critical view of society through common objects made out of uncommon materials. I bought one of these objects—a gold-plated waste bin. When I unpacked the 40cm-high bin, it seemed to glow from within, warm and radiant like the sun.

It is said of some people that they are “beautiful inside.” A browned banana, a bruised fruit, a chunk of stale bread—these ingredients still have huge potential in terms of smells, flavors and texture. The responsibility of the chef—as well as that of all of us cooking at home—is to find the inner beauty of each product and to make the most out of it in each phase of its lifespan. Straight out of the oven, a loaf of bread is ready to be served at the table and eaten as it is, still warm and fragrant, without even waiting for the crust to stop crackling. The day after, it might be sliced and toasted to make bruschetta. A day more and it is perfect to be chopped and seasoned with tomatoes to make panzanella, or to make pappa al pomodoro. On the fourth day, it can be turned into breadcrumbs for passatelli or for exquisite gratins. In this way, leftovers are reintroduced into the food chain—with extra value.

Black and white frescos by local artists Luca Zamoc and Luca Lattuga decorate the walls of the Social Tables Ghirlandina in Modena, Italy.

Black and white frescos by local artists Luca Zamoc and Luca Lattuga decorate the walls of the Social Tables Ghirlandina in Modena, Italy.

In the end, the point is to return dignity:

To an overripe tomato that is not in perfect condition but is still perfectly edible.

To an abandoned space in the suburbs.

To a person in vulnerable conditions, who is socially marginalized.

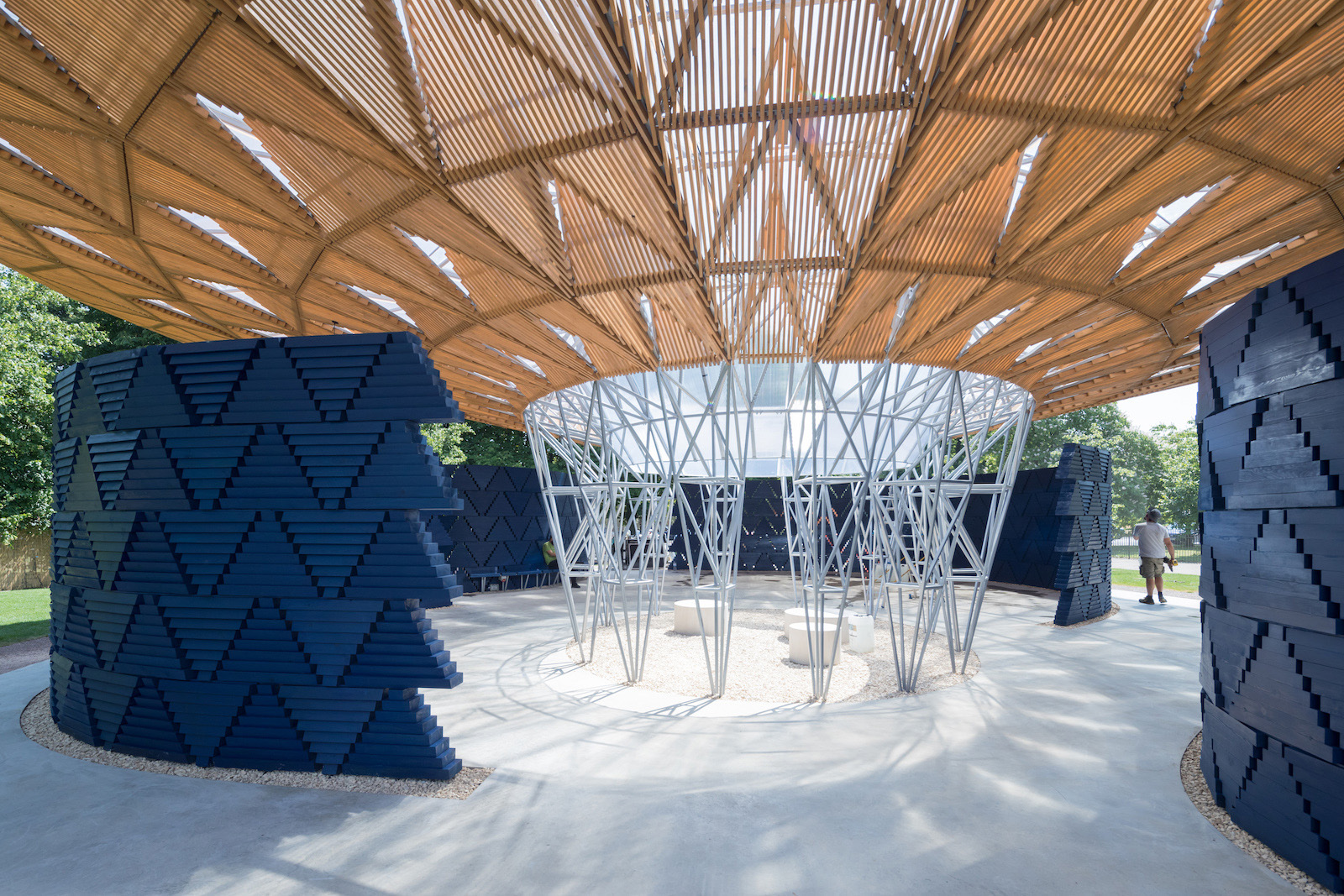

Looking at what is neglected, discarded or ignored is at the core of the mission of Food for Soul, the non-profit organization that my wife Lara and I founded in 2016. We build community kitchens around the world with the help of different people, associations and institutions. First, artists, architects and designers transform disused spaces into beautiful and inspiring hubs, complete with fratino tables—tables for 8 to 12 guests, where no one sits at the head. All equals. Chefs transform surplus ingredients into three-course meals. A team of volunteers serve those dishes directly at the table to people living in socially vulnerable conditions.

Chef Massimo Bottura cooking at Refettorio Gastromotiva in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2016.

Chef Massimo Bottura cooking at Refettorio Gastromotiva in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2016.

We started from a very simple—though, now that I look back, I’d say crazy—idea: to apply everything that we had learned in more than 20 years of experience at Osteria Francescana to a brand new model, completely unexplored and unknown to us. We distilled our experience into three tenets: quality of ideas, the power of beauty and the value of hospitality, to a community kitchen. Now we have six projects around the world: the first seed was in Milan, then came Bologna, Rio de Janeiro, Modena, London, and most recently, Paris. On March 15th, we opened Refettorio Paris in a place with great historical value: the crypt of the church of La Madeleine.

In West London, Food for Soul collaborated with designer Ilse Crawford to create a warm dining room for Refettorio Felix at St. Cuthbert’s centre. Photo by Simon Owen/Red Photographic.

In West London, Food for Soul collaborated with designer Ilse Crawford to create a warm dining room for Refettorio Felix at St. Cuthbert’s centre. Photo by Simon Owen/Red Photographic.

Any time that I visit one of these places, I ask myself, “how powerful can a meal be?” I mean, sitting around the same table, immersed in a space of art, design and beauty; sharing a meal, a good one; creating and stimulating human exchange. All this happens in front of a simple soup—made with ingredients otherwise wasted. Indeed, how powerful a meal can be.

This is why I always say—and I’ll keep repeating until I’m heard—that Food for Soul is not a charity project, but a cultural one. We are not aiming to serve as many meals as possible, and consequently feed as many people as possible. We aim to change the mindset. We want people to look at food, spaces and other people with different eyes—understanding the potential of anything and anyone. We want to make visible the invisible.

In 2016, chef Alex Atala cooked a meal using surplus ingredients donated by the catering companies that supplied the Olympic villages. Photos by Angelo Dal Bo.

In 2016, chef Alex Atala cooked a meal using surplus ingredients donated by the catering companies that supplied the Olympic villages. Photos by Angelo Dal Bo.

When we decided to open the first community kitchen in Milan, Refettorio Ambrosiano, I found myself calling all my chef friends, one by one, asking them to fly over to Italy to cook for 100 people per night. “But please,” I told them, “don’t bring your recipes with you. They’ll be useless.” Nevertheless, some of them brought their recipes anyway. The moment our food truck arrived and our team unloaded boxes of surplus cauliflower, zucchini, basil, strawberries and cheese, they would finally understand my unusual request. I could tell by the look of shock on their faces.

We collected the resulting new recipes, made out of necessity, in a book. In November 2017, we released Bread is Gold. The title came from a recipe that we used to make at Osteria Francescana—a dessert made only with breadcrumbs, milk and sugar, like the beloved milk soup of my childhood memories. If you’re only looking for a book for recipes, you might be quite disappointed. Like Artusi, you’ll find recipes for meatballs, loaves, soups, and ice cream—eventually, we had to deal with tons of stale bread, rivers of milk, and mountains of cheese rinds and overripe fruit. I like to say that Bread is Gold—again, like Artusi’s- is a book of ideas that will help you be resourceful with ingredients, no matter how fancy they are or how nice they look.

At Refettorio Gastromotiva, Brazilian artist Via Muniz’s chocolate painting of the “Last Supper” hangs on the wall.

At Refettorio Gastromotiva, Brazilian artist Via Muniz’s chocolate painting of the “Last Supper” hangs on the wall.

Food waste is one of the biggest problems of our century. Numbers are numbers. Almost one billion people are undernourished. One-third of the food we produce globally is wasted every year, including nearly four trillion apples. Just imagine how many apple pies we could make! I am an optimist and I believe that we are already making positive change, and pushing people through it with all our strength. Because, guess what: everyone can participate. Everyone can make a difference by simply cooking and sharing the most powerful tool for change: a meal.

A recipe, after all, is a solution to a problem.