The Visuality of Mutuality is a column about the ways graphic design can help support local restaurants, establish deeper roots for food sovereignty, and nourish local food ecologies.

In September 2020, Jennifer Kim closed her popular Chicago restaurant Passerotto. In the months leading up to the closing, Passerotto had switched its operations to no-contact pickup and delivery. Then, after the civil uprisings in June, the restaurant refocused its efforts toward supporting protestors and mutual aid groups. When the city reopened for outdoor dining that fall, neither Kim nor her staff felt safe working during that stage of the pandemic. So after six years, they chose to shut their doors. “It was really a decision of people vs. profit,” says Kim.

An outspoken advocate for restaurant reform while working as a chef, Kim began this next phase of her career thinking about the informal economy running alongside and underneath the traditional hospitality industry. In a notoriously mercurial industry where wages are often low and health care and other benefits are not usually offered, many restaurant workers have found other ways of supplementing their income. “The really wonderful thing about the service industry is that it is comprised not just of people who are really phenomenal at their jobs, but people who are also artists, writers, designers, printers, makers, organizers, and just overall creative geniuses,” says Kim. Furloughed, laid off, or not willing to risk their safety and the safety of others during the pandemic, many hospitality workers found themselves relying on their “side hustles” as a main source of income.

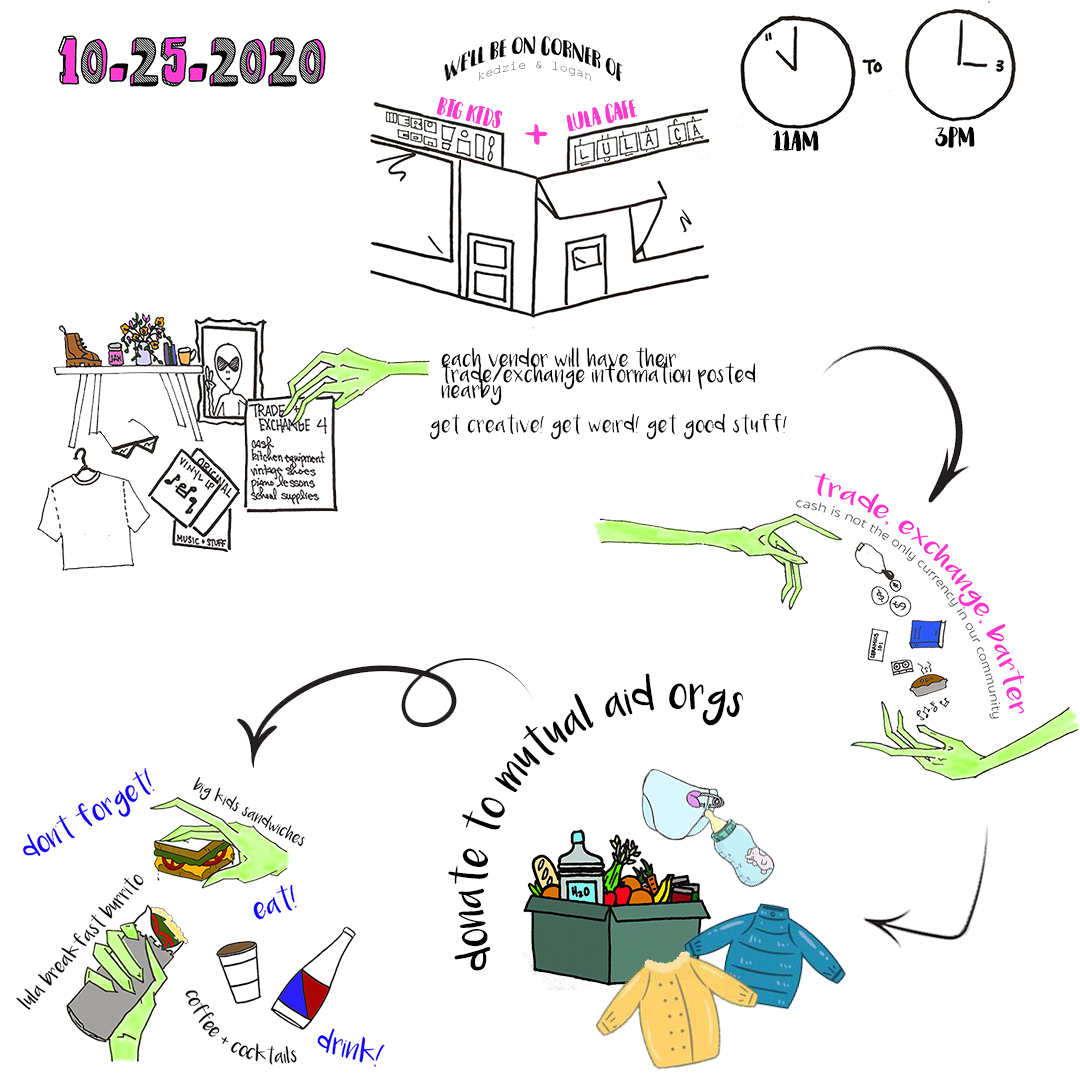

With the creation of Alt Economy, Kim wanted to build a structure and community that would help people to sustain those practices and build them into robust businesses. In October, she worked with other restaurant workers to open the Collective Care Market, where over 20 vendors sold their wares in Chicago’s Logan Square, either for cash or for barter, alongside booths where people could donate to local mutual aid organizations. In the months following, Kim set up the Alt Economy website with the intention of creating a “virtual house” for underground artists or micro-economies that couldn’t afford to set up their own ordering platforms.The community she created through the marketplace started to collaborate on one-off projects, collective e-commerce, and mutual aid focused events.

“For some people, [their business] was something that they’ve done well before the pandemic, and now it’s what they’re putting their entire focus on,” says Kim. “Others have never sold their stuff before, and were just looking for resources on how to begin. That was really the launching pad for being like, ‘Okay, we see that there’s a need for people wanting to explore alternative economies.’”

Kim says she first heard the term “alternative economies” from her friend Joey Pham of Flavor Supreme, who had read the term in Drawstring magazine. Also sometimes called an informal, circular, or community economy, an alternative economy is simply “a non-traditional labor market that’s not regulated by the city or government of any sort,” says Kim. When I speak to her in June, she is careful to note that alternative economies are economies of survival rather than sustenance, and that they are not a new idea. “This model has been in use for a very long time, and it predominantly exists within Black, brown, immigrant, undocumented and poor communities,” Kim says. “Those communities are light years ahead when it comes to conceptualizing, creating, and participating in these really robust economies.”

Kim also points me toward the paper Survival Economics: Black Informality in Chicago by University of Illinois-Chicago professor Nik Theodore and executive director of Equity and Transformation (EAT) Richard Wallace, as something that has influenced her thinking around alternative economies in Chicago in particular. The paper focuses on Black Chicagoans who have been pushed into jobs outside of the traditional market—selling cigarettes, for example, or operating in-home daycares—due to unemployment. It uses the term “hustles” to describe “income-generating activities pursued in the absence of stable employment.” In an interview with WBEZ, Theodore notes that while there is “creativity and ingenuity, entrepreneurship and drive” to be found in the informal economy, that’s not something he celebrates. The fact that an informal economy has to exist represents a failure of our system.

This nods to something I appreciate about Kim’s positioning of Alt Economy, which doesn’t glamorize the idea of “side hustles” or the precarious conditions that have necessitated an alternative economic model for hospitality workers. Still, for Kim, the closing of Passerotto offered a “regenerative moment” to pause and explore what it might look like for a hospitality industry that meets its workers’ needs. The project has shifted shape several times in its exploration of what a reimagined restaurant industry might look like. Kim and others in the Alt Economy community are experimenting with what works in hopes of generating something different from the options that currently exist. “What parts do we take from this informal economy model?” she says, “and what parts do we take from typical restaurant models? What do we want to leave behind?”

The online market ended in the spring, and lately Alt Economy has been offering a series of open-source “living worksheets” that offer templates for things like profit and loss statements and pricing food and beverage for events. Several people have reached out asking for help writing business plans, so a virtual Business Plan 101 class is in the works. If the physical and online markets gave a platform for vendors and connected a network of people interested in a different way of making a living, the next steps are aimed at offering financial resources and other information that she says have historically been kept from line level and hourly employees.

Kim is also looking toward expanding the Alt Economy community, which until recently has been mainly built through social media. “I think of my mom selling food out of the home: everything was by word of mouth and through community networks,” she says. “[With Alt Economy] the core concept is the same, but we have more accessibility to be able to reach out to people who want to participate or want to consume.”

In July, Kim embarked on a 30-day “summer tour” with creative director Justin E. Arnett-Graham of beCo and Simone Freeman of Sol Cafe and Wild Child Eats. Together, they are visiting cities across the country and working with local chefs to put on one-day pop up events to celebrate and support workers participating in the alternative economies in their city. “It’s basically partying with a purpose,” says Kim, “seeing what people in other cities are doing and asking how we can support them.”

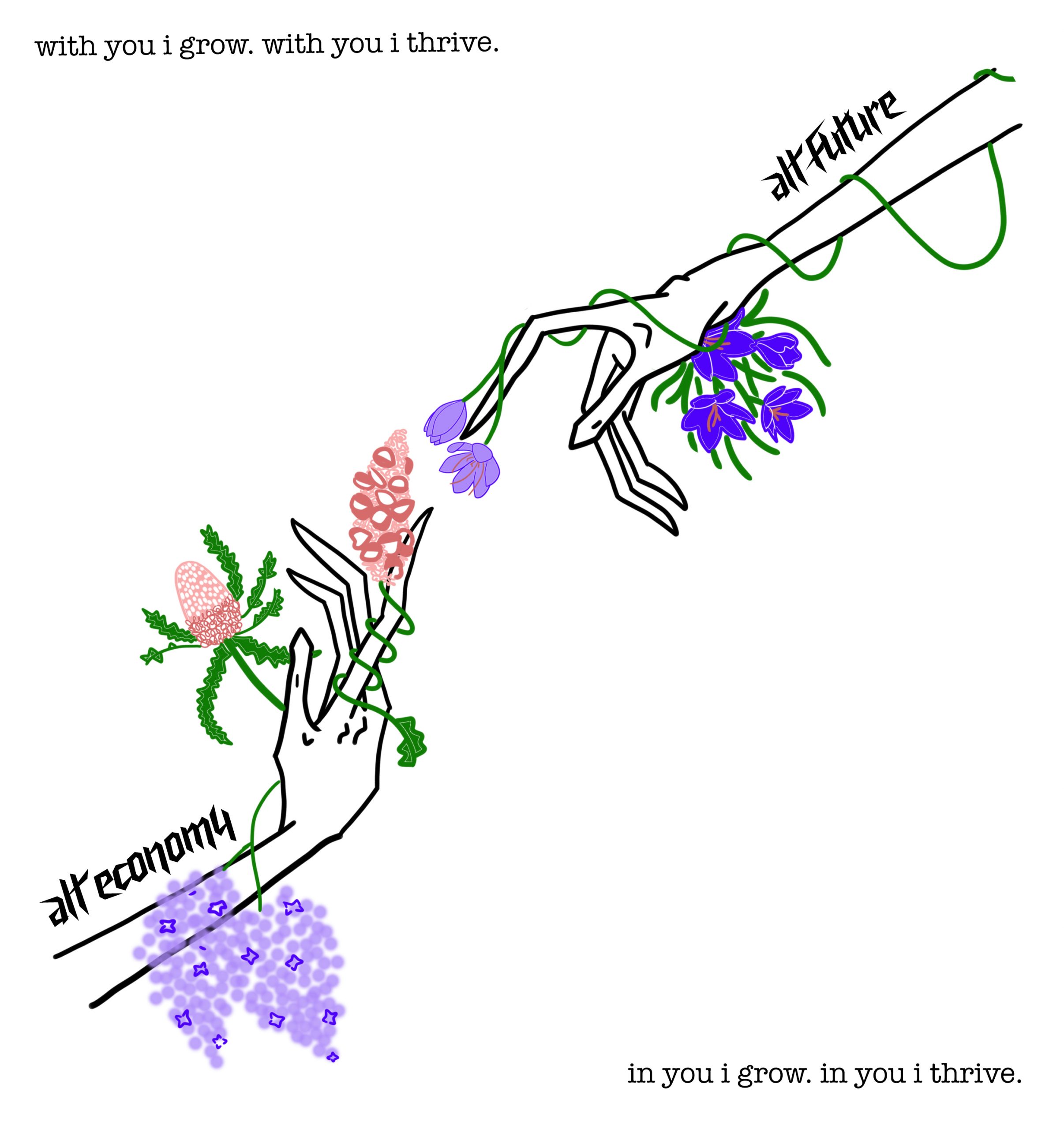

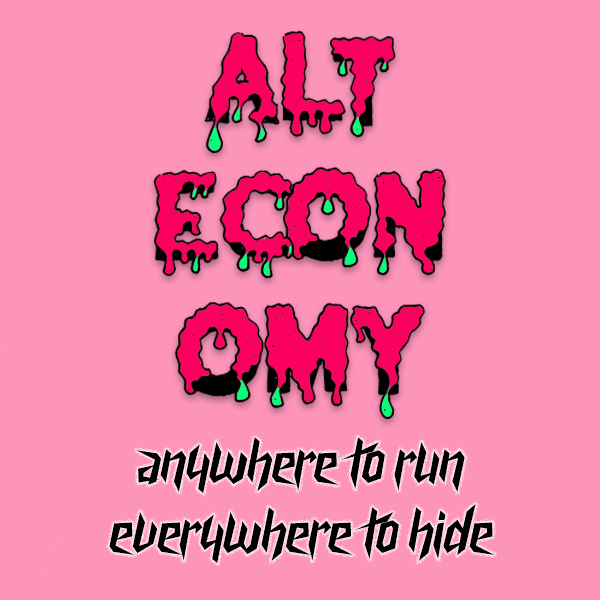

For Kim, all of the various initiatives launched under the banner of Alt Economy are working toward the same goal of giving hospitality workers alternative pathways to working for themselves. She relates this type of blueprinting and worldbuilding to speculative fiction, which is echoed in the oozing wordmark and sci-fi line drawings that punctuate Alt Economy’s branding. The effort is not to get rid of traditional restaurant models completely, but to reimagine a restaurant industry that works for the people who sustain it. “We want to sit people down and ask people, ‘What does the new hospitality movement look like for you? What does a joyful future look like for you? What is a future in which you’re thriving—What does that look and feel and smell and tastes like to you?’”