Predicting the future is a notoriously fickle business.

In a 1967 article, Time magazine heralded the approaching day when, “farmers will cultivate the soil with inaudible sound waves, work fields by computer-controlled programs, use television to monitor their remote-controlled machines.” So far, so good: believe it or not, sound waves have been shown to kill parasites and increase plant yields, and prevent unwanted algae and barnacles in fish farms. However, they finished by adding confidently, “another phenomenon in the not too distant future is square tomatoes, which, after all, could be more easily packaged by machine—and fit better in sandwiches.”

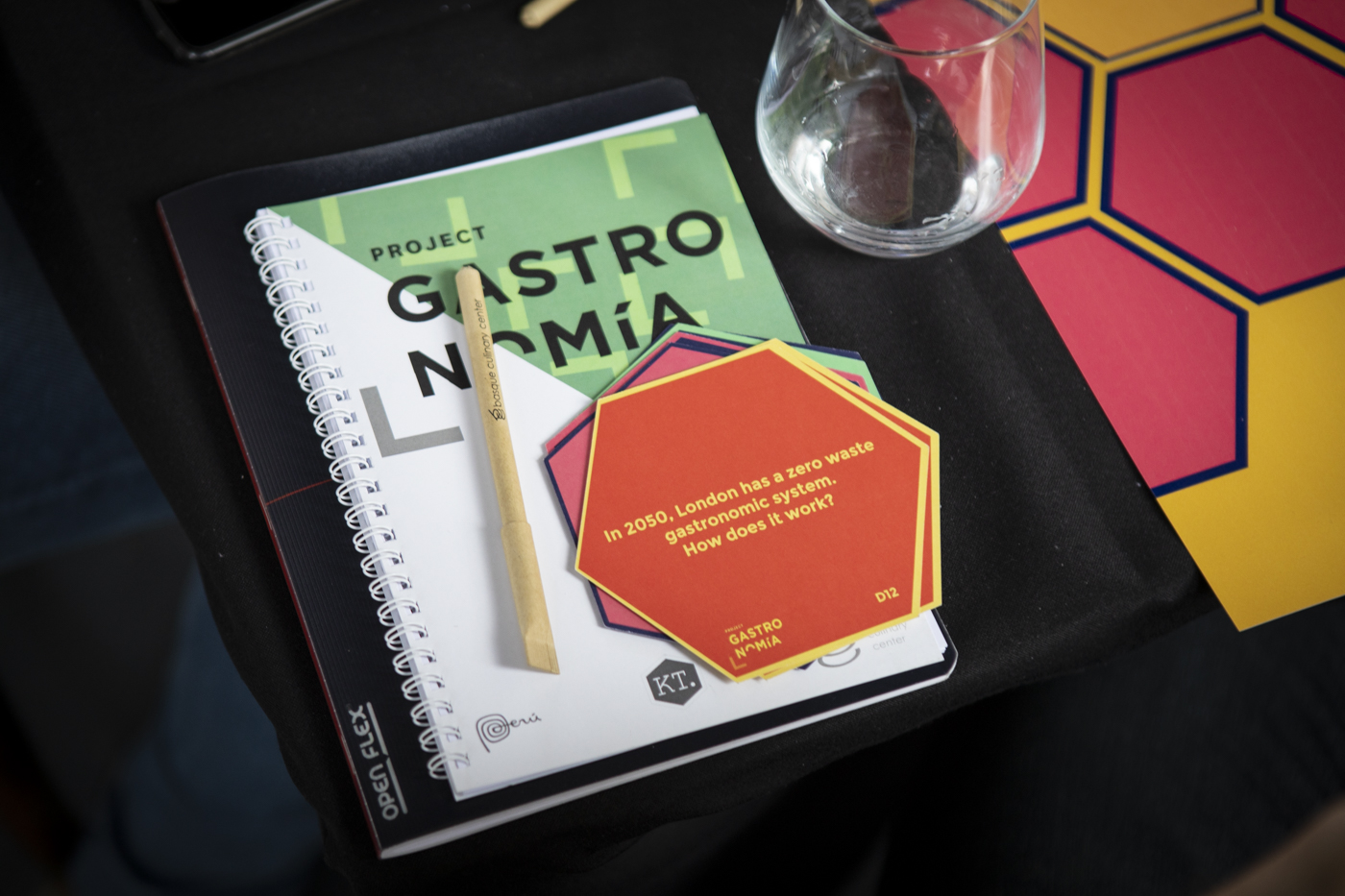

Thus it is with some trepidation that some 50 chefs, philosophers, designers, environmentalists, technologists, food scientists and food writers gathered recently in Shoreditch for Project Gastronomia, which sought to answer how Londoners will eat in 2050 through the lens of multisensory design, sensu amplo.

The day kicked off with talks from a multidisciplinary panel of experts. Afroditi Krassa, a designer who has created restaurant interiors for Dishoom and Heston Blumenthal, highlighted the changing definition of what and where a restaurant can be and how consumer demands for alternative, more expansive, dining experiences are changing these norms. Dancing on tables is set to be big, you heard it here first.

Meanwhile, brother and sister chef Virgilio and physician Malena Martinez of Mater Iniciativa—the research centre behind Virgilio’s Central Restaurante in Peru—spoke of the importance, and untapped potential, of biodiversity and traditional methods in shaping healthier, more fulfilling, gastronomic landscapes, and showcasing the narratives of cultures and ecosystems through the food that these things produce.

The import of emotions in gastronomic experiences was echoed by chef Jozef Youssef who highlighted work demonstrating how simply showing and talking about new foods to kindergarten children—to replace disgust with intrigue—was able to broaden the range of foods (broccoli! spinach!) that they were willing to eat. He also tapped further into the more conventional sense of multi sensory by raising how “sensory touch-points”—context, environment, sound, textures, colors—which form an often unnoticed scaffolding that shapes how we perceive flavour and taste, can be hacked to guide us to eat more nourishing, sustainable diets.

Food writer Bill Knott then reflected on the role of urbanism in modern, unhealthy eating compulsions, which might be ameliorated through clever multi sensory design and innovate tech—think sensors and devices for guiding diets and the increasing overlap of personalized medicine and personalized food.

This conference was part of a larger initiative run by the Basque Culinary Centre, that seeks to explore how to create a positive impact using food and gastronomy. In collaboration with Youssef’s Kitchen Theory team, they curated an incredibly thoughtful program with representation from the types of industry figures often missing, detrimentally, from similar events. To wit, Charlotte Catignani R&D Manager at Treatt, a chemical manufacturer that develops and makes flavours and fragrances, reminded us of how industry is often ahead of the curve and has been leveraging the multisensory to engage consumers for a long time.

Following the panel’s presentations and discussion, groups of attendees brainstormed their own takes on the multi-sensory future of food.

We were spared the suggestion of square Solanaceae with concepts largely focusing instead on how to promote health and social cohesion for future Londoners. An envisioned smartphone-linked living wall would provide aquaponic vegetables, herbs and fish in community-based housing, while an e-toothbrush that read a user’s biometrics first thing each morning monitored health trends, made dietary suggestions and ordered food. All of the concepts pitched were remarkably viable—10 years off being a reality?—highlighting how challenging it is to plan for a world, even just 30 years away, that will likely be incredibly different to the current one.

Regardless, the day—if anything, too short—was a resounding success. The idea of the multisensory served as a fruitful jumping off point to garner insights into the most critical challenges faced by the global food system—ecology, ethics, health, climate change, growing populations, aging populations changing appetites, protection for consumers, and food authenticity and traceability—from the panelists and lively attendees alike. For more insights, see Project Gastronomia’s post-conference report here.