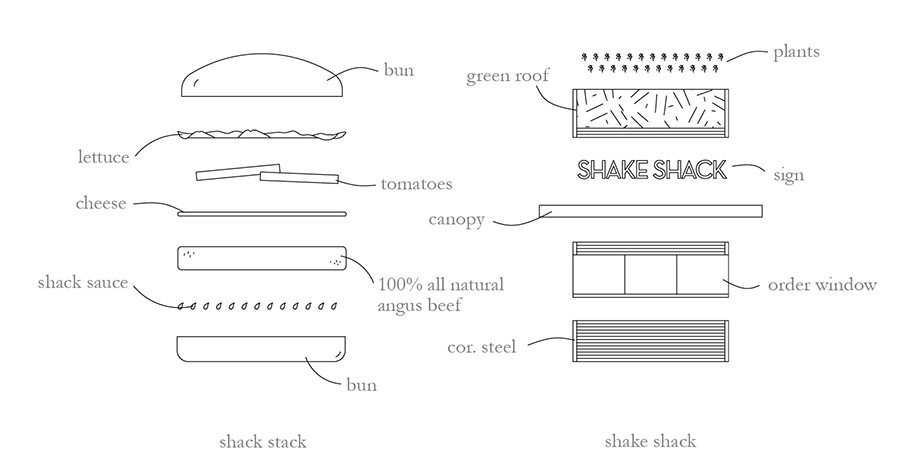

Now more than ever, design is a fundamental part of how we consume food. The packages we eat food out of are designed, the spaces we eat in are designed, and the food itself has been designed, plated or presented with intention. But attempting to define “food design” is elusive—it involves a diversity of methodologies, philosophies and priorities related to both food and the practice of design. It begs the questions: Where does design affect our eating behaviors? How do designers engage in food systems in a meaningful way? Where best does design fit into a community of advocates, chefs, scholars and journalists? Does food design aim to delight, solve, reveal or play? Can it do all? The 2nd International Conference on Food Design, held at the New School in New York City last weekend, aimed to answer some of these questions and posed thoughtful new ones.

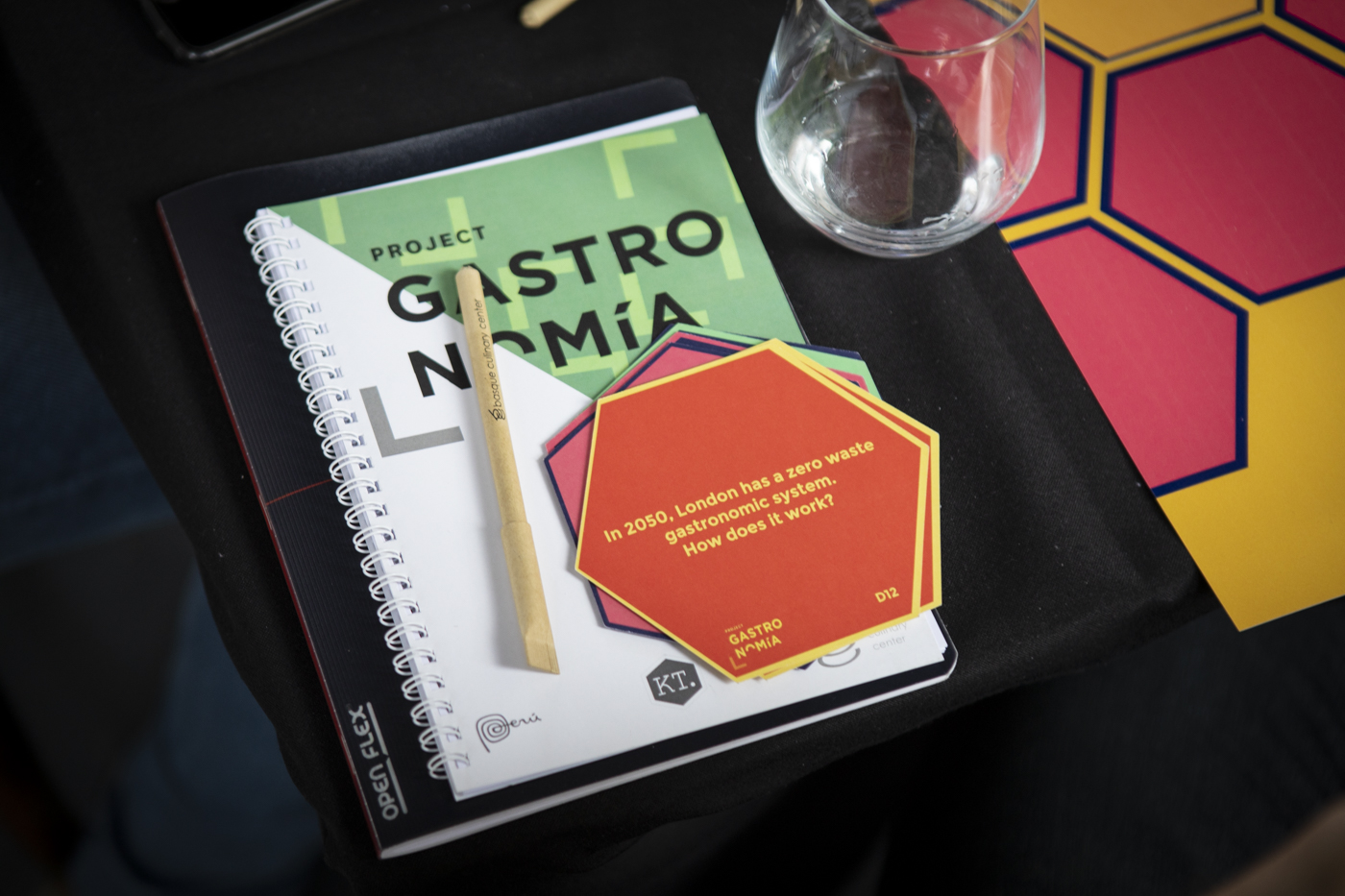

The three day conference featured an impressive array of projects, papers and research. The breadth of work created a unique feeling of shared exploration, for both participants and attendees. Sonia Massari, of the Gustolab International Institute for Food Studies (based in Italy), set the tone Friday by addressing the interdisciplinary nature of food design. Massari’s work at Gustolab serves as a testament that using “human-value-centered” design produces innovative solutions to food and health challenges.

Sonia Massari speaks to the value of human-centered design at the Gustolab

Sonia Massari speaks to the value of human-centered design at the Gustolab

Across the Atlantic, Juan José Arango Correa spoke about Latin America’s take on food design, where cultural heritage intersects social innovation. He echoed the importance of collaborative approaches. For Correa, design has the potential to improve the relationship between people and their food, particularly when it creates links between consumers and culinary traditions.

Yet another approach to the study of food design came from New Zealand. Richard Mitchell showcased work coming from The Food Design Institute at Otago Polytechnic, a hospitality program dedicated to food experience design. The institute produces dining events based on innovative concepts and narratives. At one gala, which chronicled the history of food innovation in New Zealand, diners encountered a wall of spoons off which to eat, and smoking, table-side preparation of dishes occurred in blacklight. Mitchell’s program brings design into hospitality, and ultimately aims to create space for storytelling between producer and consumer.

More tangible representations of food design included research proving that atmospheric elements can change how much, or what kind of wine we purchase at a restaurant. Domgmin Lee, a researcher from South Korea, set up a series of experiments in Korean wine bars, where she determined that auditory cues (playing French music instead of Korean pop music) increased the likelihood that diners would order wine with their meal. In addition, visual cues (“French” themed graphics on a placemat) caused people to purchase higher priced wines, presumably the more expensive French ones.

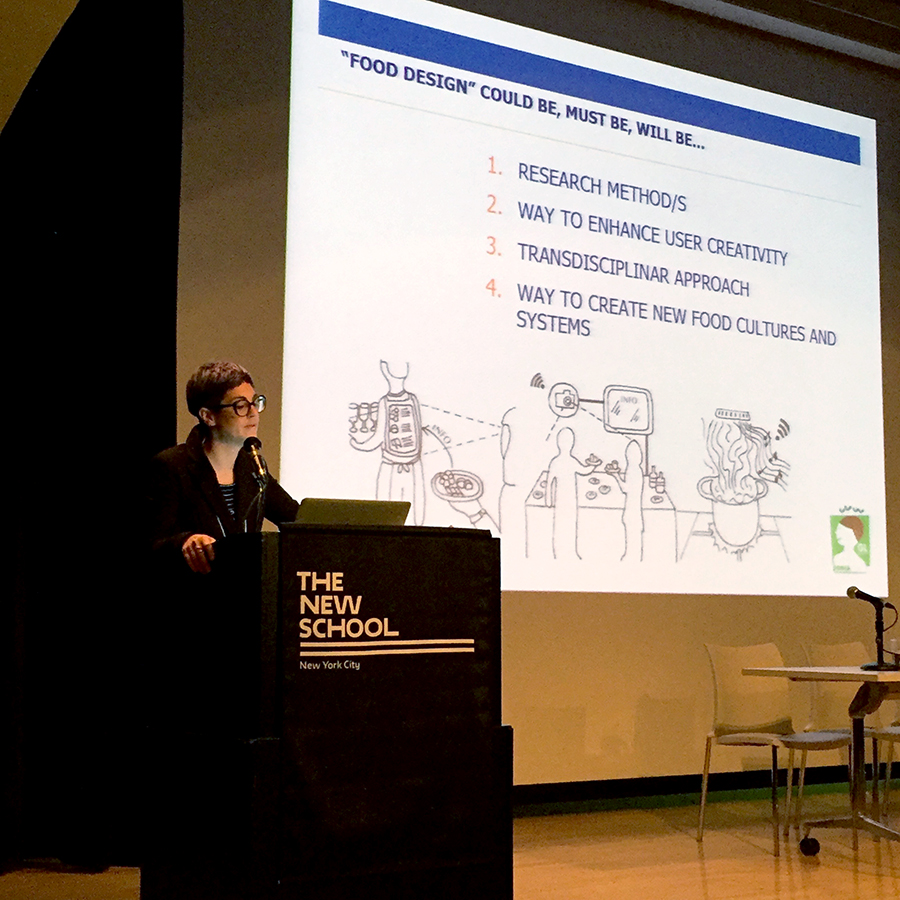

Fast food diagrams by Andrew Fu

Fast food diagrams by Andrew Fu

Several installations and projects showed physical manifestations of “food design.” A new media designer from India built interactive displays which revealed the narratives in the urban food chain, while an architect from Cornell showcased a fascinating investigation into how burger joints’ design interplays with the composition of the burgers themselves. To aid those suffering from sight loss, a designer from London shared his line of kitchen equipment that provides subtle sensory feedback to the user. Again and again, the case was made for design’s fundamental connection with how we eat, and it’s potential for expansion.

Simran Chopra’s interactive displays relating to the urban food chain in India

The awe-inspiring keynote address from Emilie Baltz only served to perfectly punctuate that point. She shared her own story of how food became such a powerful venue for performance and design. From a childhood in Illinois with a French mother, to an almost accidental discovery of industrial design, to success with a hilarious, if not audacious, junk food cookbook, she truly embodies the adventurous side of food design. She embraces the power of food to delight. Her work, which includes the Museum of Sex’s Play bar and a “Circuit of the Senses” dinner created for Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, spoke to the power of playfulness and creativity in eating experiences.

An interactive eating experience by Emilie Baltz. Photo by Colin Conces

An interactive eating experience by Emilie Baltz. Photo by Colin Conces

And that’s why design has strong potential in the food world—we can analyze complex structures and problems, and we have the potential to infuse humor and awe into applications for change. Through a creative, collaborative approach, designers can reveal ideas, solutions, and narratives behind our daily eating experiences in a meaningful way. Whether attempting to solve food systems issues, or simply using food as a means to communicate and engage, designers clearly have an important role to play in the future of food.