Methods & Provisions is a series documenting the memories, rituals and soundtracks of people who love food.

During the apex of the pandemic, Faith Kim left New York City to return to Korea, where her extended family currently resides. There, the communications designer and free diver spent the last year with Jeju Island’s haenyeos—a community of women who maintain the traditional profession of harvesting edible sea creatures from the ocean. In our conversation, Faith discusses making peace with forces of nature, the tensions in preserving tradition, and what it means to design for your community. Faith refers to the haenyeos as “gardeners of the ocean”—women who have cultivated a relationship of interdependence with the sea through consistent communion and stewardship. While the future of the profession remains unpredictable due to the impact of climate change and human-generated waste on the ocean, such rituals and routines of care chart a path forward for a sustainable future in food.

Isabel Ling:

What propelled you to leave your design job and move to Korea?

Faith Kim:

Leaving my job and moving to Korea was a difficult decision made during a difficult time in the world. The pandemic, Black Lives Matter protests, and the feeling of global uncertainty were my motivators to make a change. I questioned my everyday work life, felt unsafe, confused, and most importantly wanted my family. I felt ready to go back to the motherland to figure out who I was and what I wanted.

My lack of knowledge about my own family history inspired me to go to the obvious source: grandma and grandpa. As soon as I reached Korea, I went straight to Byeongpoong Island where they live. This small southern island is my grandparents’ hometown and is mostly an agricultural island filled with vegetable and salt farms. I spent 3 months fishing with my grandpa, helping my grandma cook, and listening to the stories they couldn’t tell me the past 24 years of my life. Most days, I took long walks and chatted with local grammys. Listening to new stories and absorbing the environment around me made a big impact on me and my work. Finding inspiration in my everyday interactions, rituals, and conversations on this specific island made me realize the importance of being present.

IL:

How did you end up joining the haenyeos?

FK:

Haenyeo are designated cultural treasures, so if you’re Korean it’s pretty common to know about their work. After my dad made a joke about haenyeo school, I started researching it and came across Jeju Hansupul Haenyeo School, which is one of the oldest programs that preserves and teaches haenyeo culture.

It wasn’t easy to join, though. When I first approached a group of haenyeos from the neighboring village, Yong eun dong, they kept their distance and it was very clear that it would take some time to gain their trust. It started off with me greeting the divers every time I biked past them. For months, I stopped by everyday to make small talk and build a friendship. The moment they greeted me back was the day I knew that they recognized me and were willing to get to know me. They taught me new Jeju dialects, how to crack sea urchins, and eventually shared their personal stories with me. Some days we would hang out and drink rice wine with fried abalone after their long day. I felt comfortable enough to ask if I could go diving with them but they denied my request multiple times for safety reasons. It was only after months of hanging out that they agreed to have me go into the water on their last day of sea urchin season.

IL:

What was that like?

FK:

Haenyeos are hustlers. They wake up at 5AM and meet at the changing room for a cup of coffee and a chat before going into the water. After about an hour of local gossip, they put on their tight rubber wet suits and weights. Then, they prepare their goggles by using mugwort and spit as anti-fog. Once geared up, we walked over to the entrance of the ocean where grandmas from other neighborhoods were also preparing. The haenyeos waddle into the ocean with their fins and dive in with their special hoe used to detach the sea urchins in between the rock crevasses. They swim up and down for 5-6 hours till around noon. After cleansing the salt off of their bodies, they prepare for another 3-4 hours of collecting the uni inside of the urchin.

Haenyeos are responsible for their own harvests all year round—they are not just gatherers but gardeners and protectors of the ocean

IL:

How has diving with haenyeo changed your perception and relationship with food?

FK:

Interacting with the ocean, I became more attached and connected to the underwater world. In the beginning it took a whole month of diving to locate and simply see conches. The obstacle lay in understanding where they lived and how to spot them. As time went on, I started to recognize certain fish, and was able to locate the conches and navigate underwater comfortably. Once it got easier to spot and catch conches, I realized that it’s really up to you to decide if the baby conches are worth catching. It’s exciting to harvest but I learned that it’s just as important to let go of the shellfish that needs more growth. Knowing that greed can end the natural cycle and hurt your future ability to make a profit, you prioritize maintaining a sustainable relationship when tending the animals. Normally you just see the conches for sale in stores but I was lucky enough to experience them and their intimate relationship with their natural habitat and the personal care that goes into catching them firsthand. Diving with the haenyeos showed me how reliant we are on nature and how most of our food comes from these hard-working processes that we don’t usually get to see [throughout] most of our lives. When you’re close to the source it makes you want to protect the beauty of it and its offerings.

The haenyeo profession started with young girls who jumped in the water with nothing but their clothes to catch wildlife they would then sell at the market. As time went on, more structure was established for their jobs and an overarching organization was created. Now, there are fishing village cooperatives that shape the politics for the many Haenyeo groups in different locations. For example, they make specific rules and restrictions of when you can catch and when because you need to be attuned to the natural cycle. In order to sustain this cycle, within the three or four months of off season they also have to tend to these animals and care for them. For sea conches, haenyeos go out into the water to relocate them and protect them every day. In some neighborhoods haenyeos also act as lifeguards to prevent outsiders from catching and are paid to have weekly shifts. Haenyeos are responsible for their own harvests all year round—they are not just gatherers but gardeners and protectors of the ocean.

As people who make their living off of the ocean, and also other living creatures they emphasize a communion and awareness between your body, your greed, and your living as well as the forces of nature.

The haenyeos told us that when you spot an octopus you always need to come up for air first. Octopus are expensive and worth a lot of money, so if you get too excited and forget to breathe you put yourself in a dangerous situation. It’s vital to be aware of your breath and know when to stop. At the end of the day your life is the most important and you can never underestimate the ocean’s dangers which is why haenyeos never work alone. For every dive they go in with their groups. They constantly check on each other out in the ocean by whistling when they come up for air.

When you create for your community, you have more agency over your work

IL:

So in a way, the haenyeo are also acting as stewards to the ocean in their reliance on it for profit.

FK:

Yes! As a younger person who wants to preserve the haenyeo profession and this tradition, I think that protecting the ocean is an important part of continuing this practice. There’s been a significant decrease in haenyeos but also wild shellfish in the sea. One grammy diver once told me that she used to catch abalone the size of her face but is now impossible to see in the wild because they caught them all. Their methods developed into farming and protecting the shellfish where they relocate and prohibit catching during the off season. But long term, it seems difficult to maintain if the oceans get littered and humans create uninhabitable environments for the animals. If there isn’t a healthy ocean, there won’t be haenyeos at all.

Unfortunately the one common species I saw in all of the oceans was trash. I always knew that our fight against climate change wasn’t going too well but when you directly see the litter at the bottom of your dive it’s hard to ignore. Towards the end of the program most of us would go diving to collect trash. Plogging became a ritual and being conscious about my own waste came naturally. Haenyeos were forced into the sea to survive but now it’s our turn to try and protect the sea so that it can continue to live on with us.

IL:

What was it like to be a part of this community of women?

FK:

There was tension between the younger divers and the older generation about what it meant to be a haenyeo. When you meet a haenyeo they are always shocked to see younger people showing interest in their work and immediately suggest that you shouldn’t do it. To them diving was not just a job but a mode of survival. These women started diving when they were as young as 10 years old to feed family members and make money. It wasn’t a choice for them as it is now for the newer divers. It’s interesting because their profession, which came out of necessity, led women to hold positions of power in a culture that is quite patriarchal, which inspires the new divers.

It wasn’t until I was able to speak to them in person that I realized that their initial hesitant reaction to welcoming new divers stemmed from the pain from how their professions started. I felt really lucky to be able to ask these questions because they never talk about the good aspects of diving until you ask. A big topic was how free they felt, physically and mentally, underwater. Diving was a forced meditation for a lot of these grannies. The silence of the ocean and awareness of their bodies helped clear their minds. It was also super inspiring to see some of the older divers who had trouble walking on land go in and wade freely in the ocean.

IL:

Were there any specific rituals that were important to harvesting from the ocean?

FK:

‘Haenyeo-kut’ is a shamanic ritual conducted by the community of Haenyeos as a group to pray for good luck. “Kut” is the name of the practice itself and is held widely in Korea even outside of Jeju Island. Traditionally on Jeju these rituals were held to protect the safety of fishermen and young divers as well as hopes for an abundance of livelihood. They are usually held at certain times of the year as a big festival but can be held by individuals for different issues and needs. I was lucky enough to see a Kut on the boat of my grandparents I was living with. The grandma was a Haenyeo and the grandpa had a fishing boat.

This ritual in particular was an offering to the Ocean Gods to protect the boat, the captain, and to yield large profits for the year. Throughout the long ceremony a shaman and her apprentices are accompanied with various instruments and sounds. They perform a series of chants and dances with their presented offerings. Depending on the importance of the ritual offerings usually consist of rice, fruits, alcohol, dried fish, rice cake, and sometimes even a whole pig or cow. Shamanism in Korea goes way back to prehistoric times and I think a lot of people believe this god is an ancestor, that we are all a part of the same lineage. It ties back to how in Korea respecting your ancestors is embedded in our culture and we think about future generations. These rituals give us access to ask and thank our past ancestors for their blessings.

IL:

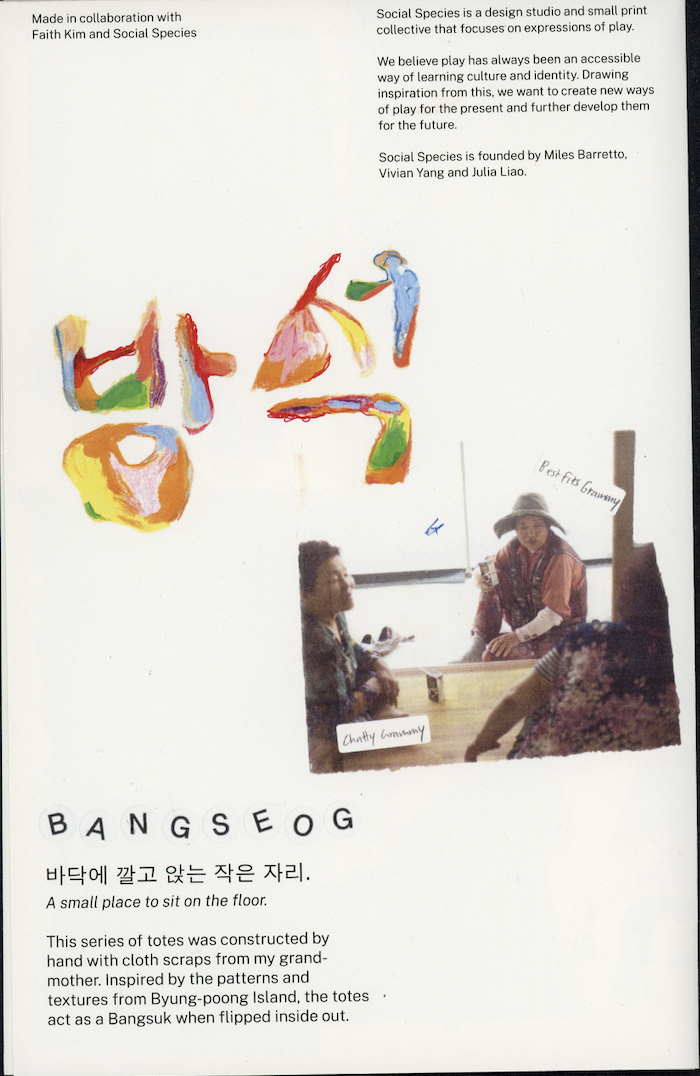

You recently collaborated with Social Species on a series of totes inspired by your grandma and your experience in Korea. Could you speak more about that?

FK:

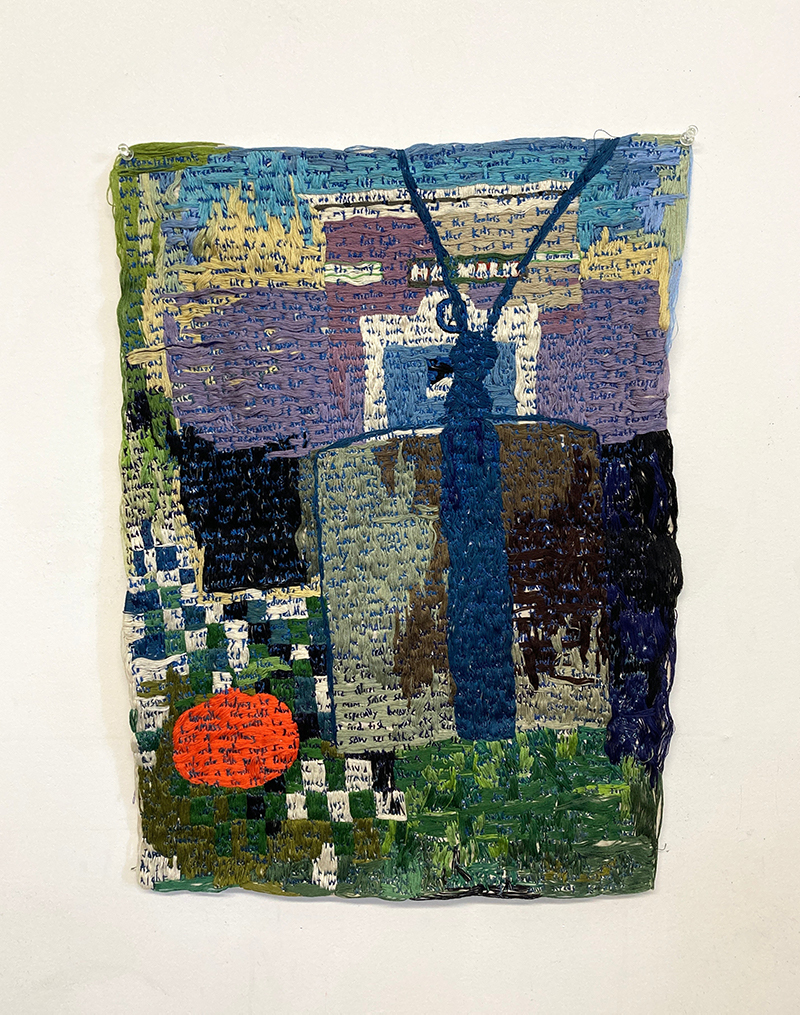

My grandma’s skills are unmatched when it comes to large, hand stitched compositions of her signature bonnet girl patterns. We’ve always bonded over our creative projects so when I came back to Korea we immediately spent a lot of time catching up and quilting together.

With the amazing support from Social Species’ Vivian Yang, Miles Barretto, and Julia Liao, we launched a series of tote bags made with the scrap fabrics from my grandma and thrifted button downs from local flea markets. The colors and patterns were inspired by the flowers and textures I would see on our long walks. During my time on Byeongpoong Island I spent a lot of time with the neighborhood grammys who would casually stop by to sit on the floor and have a chat. In Korea sitting on the floor is part of our culture and so each tote is a seat cushion (방석, bang-suk) when flipped inside out. In hopes of new connections for new people, the bag creates a small place to sit wherever you go. We are planning to continue this production of smaller scale projects in the future.

The direction for this launch was based on the Korean word Jeong. Jeong is a word to describe the emotional connection that builds over time with people and places. It’s different from love or friendship in a sense that it deepens and grows stronger as time goes on. It’s an important Korean value built on the essence of kindness. I think some personal examples of jeong I experienced on the island is when the local chili farmer gave us a ride home, or when the local bus driver stopped by to give us fish he caught, and the fact that my grandma always had snacks prepared for the local grannies who would stop by.

IL:

You’re back in the States now working in design. How has your experience influenced your design practice?

FK:

As a designer, I’ve always been really interested in breaking down visual stimuli and why it can be effective. That’s why I was interested in visual identity, because you are helping a client who has an idea of who they want to be and to translate that is a really interesting thing because they can be whatever they are, and what they want to express.

This past year forced me to think about why and for whom I make work for. Luckily these answers came naturally for me through reconnecting with family and meeting new people on Jeju Island. With life’s unpredictabilities there came unforeseen project opportunities. For example, a couple projects I’m currently working on are designing this year’s yearbook for Jeju Hansupul Haenyeo School and creating a brochure for the vegan cafe, AndYou Cafe, where I worked part time while diving. I’ve also been working closely with Nia Ono on multiple, exciting projects that I never expected to do. I’ve learned that when you create for your community, you have more agency over your work.

Listen to Faith’s curated playlist below: