Eduardo ‘Lalo’ Ángeles Carreño, a fourth-generation mezcal producer, puts his trust in the sanctity of mezcal. For Mexicans, mezcal is la bebida de los dioses—the drink of the gods—and Lalo wants one thing to be abundantly clear to those consuming it: no matter the cache it may carry, mezcal is not a trend.

On an arid October morning, Lalo greeted me at the entrance of his palenque in Santa Catarina Minas, a small town south of Oaxaca City. Smoke gently rose from the furnace beside his house, thickening the air with an aroma of scorched agave stocks, or piñas. The Ángeles family is renowned as the “the mezcal superstars” of Oaxaca, as they have used the traditional distillation process since 1978.

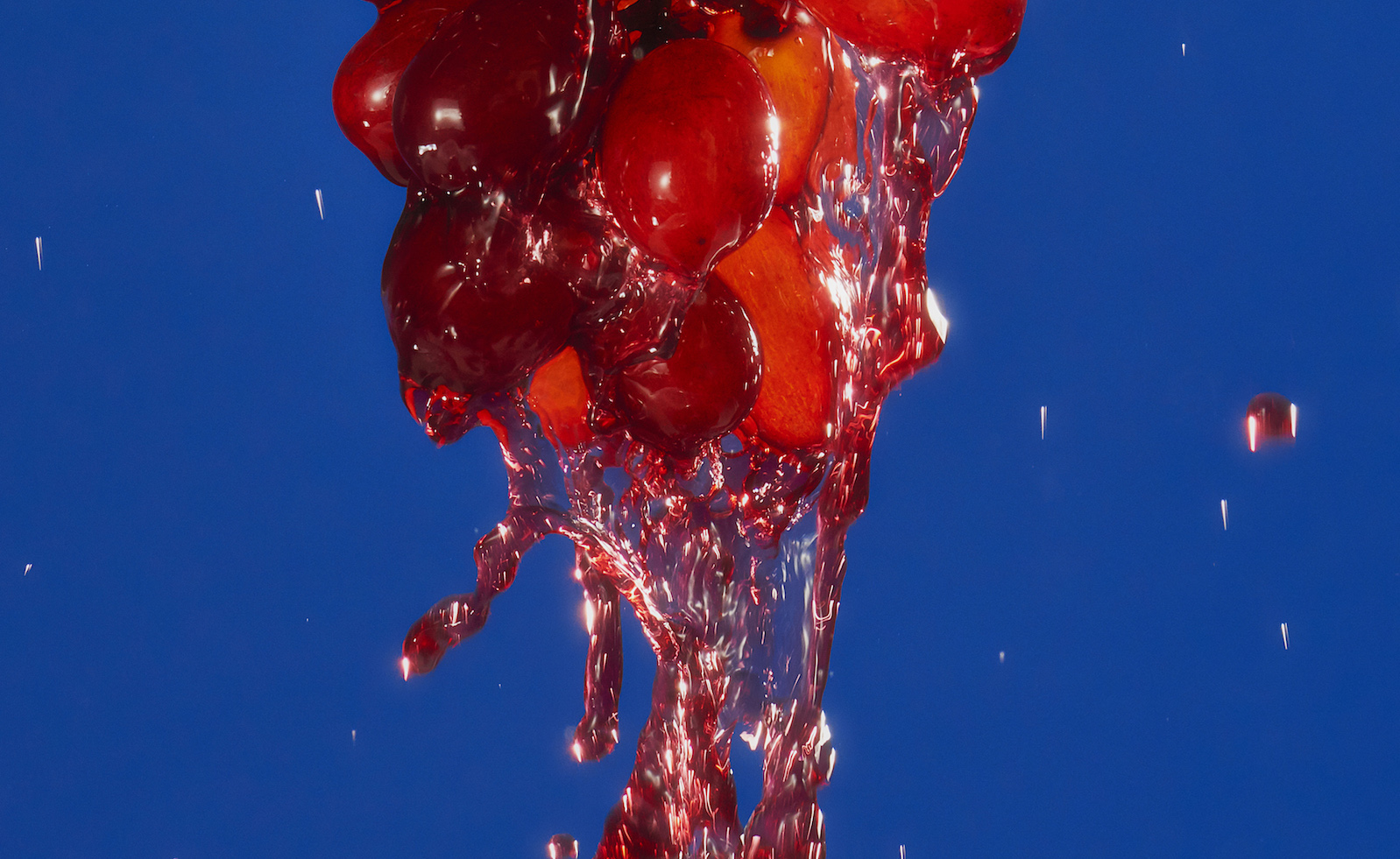

Lalo paused his work to show me the adobe where he and his staff produce small-batch mezcal. He then taught me how to drink the spirit properly—sipped slowly, straight, and held in the mouth between sips so it becomes diluted—then savored and swallowed. It was smoky, yet sweet. Strong, with a delicious burn. The maguey plant, from which mezcal is distilled, is a member of Mexico’s extensive family of agaves. The smoky flavor is born from the heart of the plant, known as the piña. Piñas will roast in a stone pit over a wood fire for nearly a week. Once removed, their juices can be extracted, fermented, and distilled. The giants of the industry have since shrunk the process down to a day and a half using machinery, since the complexities of the traditional process cannot accommodate the climbing demand for mezcal worldwide. The sugars fail to reach full concentration, resulting in a lower quality product.

“Mezcal is an essential part of our country,” said Lalo. “It is the farmer’s drink, and although corn has always been number one in all of Central America, mezcal was always second.”

According to Toltec legend, the culture of mezcal and the maguey plant constitutes heritage, wisdom, and indigenous mythology. Patécatl and Mayahuel—the god and goddess of the maguey—represent the plant itself, deified. Patécatl discovered the ocpatli root, which expedites the fermentation process. Thus, his name translates as “the one from the land of medicine.” Mayahuel embodies the fertility and nutrience of the maguey, regarded by Oaxacans as “the mother plant” for its vast range of medicinal properties and uses.

The exchange of mezcal between small-batch distillers and the neighboring families with whom they maintain relationships is intimate, humble, and fairly exclusive. Oaxacans will rarely buy labeled mezcal. Instead, a local supplier or friend will pay a regular visit, selling by the liter. Many farmers in Oaxaca uphold the tradition of consuming mezcal three times a day — once in the morning to clarify the senses and cleanse the gums, once in the afternoon for the same effect, and again at night to relax the body. Since the first evidence of mezcal’s distillation over 2,000 years ago, mothers have used it to numb babies’ gums when they are teething. Aguamiel is scraped from maguey leaves to treat back aches, sprains, and blows to the body. Piña ashes are used to treat stomach swelling, which is common among those who have dedicated their lives to physical labor. Ixtle (the Otomi word for maguey fiber) is used to make twine and cloth, while raw maguey fibers are used to build adobe walls. “Nothing goes to waste in Mexico,” said Lalo.

The plant’s medicinal properties did not go unnoticed by the Spaniards, following their conquest of the Aztec Empire in 1519. Francisco Hernández, doctor to Philip II of Spain, was quickly drawn to its cure-all potential, using it to treat multiple members of the crown. The Spaniards, however, disapproved of the tradition of mezcal consumption. Drunkenness was punished with death, as part of the crown’s strategy to decimate Aztec culture. Prohibition led to the formation of many underground alliances; those who had been persecuted by the Spanish crown sought refuge in highly protected bars, where no representative of authority was allowed entry. Oppression was shared over drinks, as such establishments were some of the only places of salvation for the vanquished.

“Mezcal is the first thing offered at every wedding, every baptism, any party,” said Lalo. His own company, Lalocura, continues to employ horses for labor and clay pots for distillation, following the traditional process. The unparalleled quality of his mezcal is the result of this age-old approach. The Spaniards replaced the use of clay with copper during the Inquisition; other mezcal brands like Monte Alban have long since replaced horses with machinery.

The traditional copa (cup) of mezcal can be found at a mezcaleria in any major city, but more often than not, the spirit’s rich flavor is simply shaken into a cocktail. Its lure was embraced by the North American market in the late 1990’s as a “new and cache” mixology concept, and as a result, the now global fad that is a mezcal cocktail exists within a bubble that is entirely foreign to Oaxacans.

“Changing the understanding of mezcal isn’t the point, because there is no understanding of mezcal in the first place,” said Lalo. It was Mexico’s third-largest alcoholic export in 2016 behind beer and tequila, generating more than $26 million, according to Mexico’s Department of Agriculture. Although the spike has brought business to small towns in the Mezquital Valley that were desperate for any form of an economic boost, it has also placed an urgent call on the industry for reform. Mass-production has forced the harvest of younger magueyes, despite the quality of a mezcal depending on the full maturation of a plant, which can take between 7 and 25 years.

In order to bottle, sell, and import, a distillery’s equipment and process must be routinely evaluated to insure that it honors the Appellation of Origin, enforced by Mexico’s Department of Agriculture in 1995. That being said, the effort to produce and market it as a premium product outside of Mexico has a relatively short history. What is most frustrating for Lalo is that these parameters, deeming a mezcal as “certifiably authentic” or otherwise, were arrived upon without input from farmers, who are required to pay a hefty fee in order to obtain certification. “Those who bring in money are the ones creating the guidelines for how to ‘properly’ practice a tradition that belongs to us, not to them,” he said. “Big companies need qualified workers with the right intentions, education, and some pride in what they’re doing.” In the past two years alone, Lalo has attended multiple events for members of the industry that are focused on making the process more sustainable, each hosted by large corporations and private investors from all ends of the globe, to whom he refers as “the mafia.” At almost every convention, he is the only farmer in the room.

In 2017, close to 80% of the industry’s profit was pocketed by mega-companies like Pernod Ricard and Zignum (a Mexican company originally founded by a Coca-Cola bottler), many of which have bought out the small family companies that value land reforestation and waste management first and foremost. For those simply purchasing the torch, the preservation of endangered magueys and use of natural insecticides comes second to supplying the market. “That, to us, as farmers and as Mexicans, is an insult,” said Lalo.

Oaxaca has long been one of Mexico’s most impoverished states — in Santiago Matatlán, the “motherland” of mezcal production, a majority of the liquid waste from scorched magueyes is emptied into the Santiago River. The excess acid pollutes the water, killing the fish and plantlife. Oaxaca’s outskirts are home to the oldest family-owned palenques; because funding for proper waste management is entirely out of reach for small-scale operations like these, increased demand has led to increased water pollution and land degradation.

Having studied agro-engineering, Lalo has long observed how Oaxaca’s farmers have been impacted by the Green Revolution that preceded him. Chemical insecticides became an integral part of Mexico’s agriculture after their debut in the 1940’s, making the prospect of a system reset unfathomable for old-school farmers. Lalo is without the resources he would need to ignite a revolution beyond Santa Catarina Minas, but he does plan on returning to his alma mater to facilitate a dialogue around the urgency of rescuing the old process and reclaiming ownership of the spirit’s original magic.

Luckily, he’s not alone—local-approved distillery Los Danzantes is staffed by a strong team of locals who are familiar with Oaxaca’s bioregion and the complexity of the plant, so their solutions are ahead of the curve. Alongside Los Danzantes, the Ocotlan Valley’s University of Cioppino has assembled a team of students, biologists, and agro engineers to clone endangered magueys with the hope of saving them from extinction. “Right now we are micro-processing,” says conservation specialist Jair Juan López, who has directed the project since its genesis in 2016. He won’t be able to assess the project’s impact until the first test group reaches full maturation in 2021. “We’re trying to adapt the rarest types so that when they’re transplanted from the greenhouse to the field, they’ll survive.”

Quotes from Eduardo ‘Lalo’ Ángeles Carreño have been translated from Spanish to English.