This is part three of a three-part series on coffee in India. Read Part 1: Coffee in the Field, the Science and History of Coffee Cultivation in Chikmagalur and Part 2: Coffee in the Cup, Roasting and Brewing in Indian Coffee Culture here.

Coffee in India has come a long way since the 1600’s and if we are keen to keep brewing it for the next 1000 years, Arshiya Bose has the right recipe.

“We feel it will take us time to restore forests and enable producers to feel fully empowered to make good ecological choices. More so, we want whatever positive changes that occur to stick around long after we are gone. This long-term effort is what we call the 1000-year brew.“

But how do other planters, roasters and cuppers see the future of coffee in India?

Many planters are conflicted with the idea of “third wave of coffee.” In the past, coffee chains like Cafe Coffee Day owned or acquired estates, harvested, roasted and sold their own coffee. They controlled their entire supply chain from bean to cup.

The third wave coffee movement has introduced a new player in the supply chain. These coffee entrepreneurs want to connect farmers to coffee drinkers through their specialty coffee brands In some ways it has created a revolution that makes farmers believe that that their coffee has value to be sold in a premier market. But planters say their margins haven’t increased much.

“Coffee is a high margin product. But the main point of the third wave movement is to take that excessive high margin and share it with the farmer.” says Rishwin Devaya, owner of Riverside Coffee. “The farmer is getting maybe a 5% increase for this concept of traceability and sustainability.”

As brands advocate for trust and transparency in the system, does this really make the system better than how it was before? Are we really eating or drinking better for the planet, for farmers and for ourselves?

Riverside Coffee has a cafe on-site.

Riverside Coffee has a cafe on-site.

Rishwin believes that this coffee resurgence is giving many estates and farmers a platform and a market to value their beans but there are many taking advantage of this movement.

“Now I’m setting up a cafe and a roaster on my fathers estate, so I can prove to myself and to people that this coffee is coming from this farm.”

Not just about traceability, Rishwin is building a circular ecosystem at the estate. With four rooms, 30 seater cafe, an espresso machine, he wants to be one of the few places that takes full responsibility for the coffee bean — from berry to grinds — making sure it never leaves the premises.

“Sustainability and an ethical food chain is supposed to cure a farmers woes. You deserve the price for the work that you have put in. To maintain an environmentally friendly and biodiverse ecosystem and to sell all my produce directly in the market at retail price. This is my dream for every farmer,” says Rishwin.

For those who can’t experience the Western Ghats in a setting like at Riverside, Rooted Objects gives consumers the opportunity to bring part of that biodiversity into their homes.

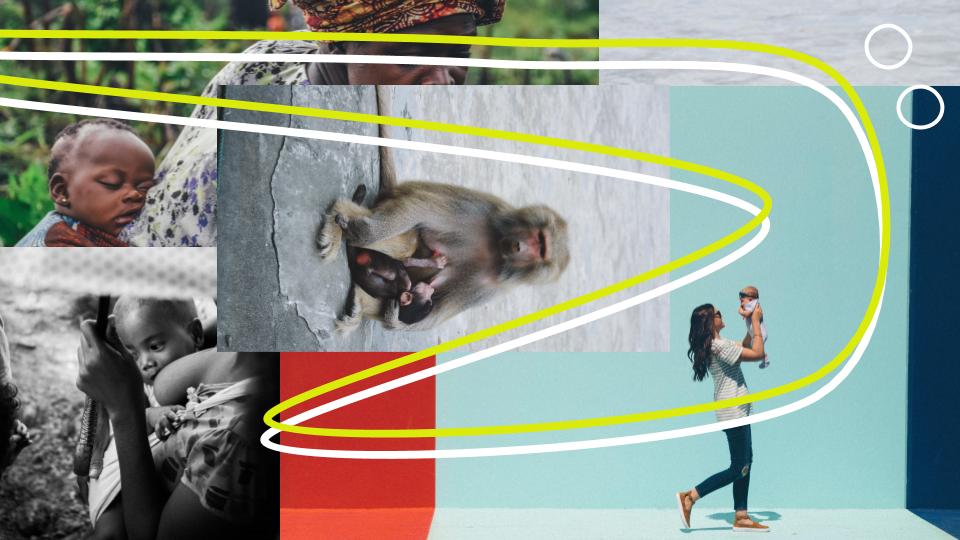

Upcycled side table made by Rooted Objects.

Upcycled side table made by Rooted Objects.

Rooted Objects is not just a platform for sustainable clothing, home decor and beauty products but is also a platform for channelising consumer behaviour. In an interview with The Hindu, co-founder Kiran Nambiar shares, “In India, sustainability is everywhere, there are so many amazing people who are working on products that relate to sustainability. Being sustainable is about responsibility to the planet in terms of how you make a product, what materials you use to make it”.

Rooted Objects works with Kerehaklu Estate to showcase and tell stories of the beauty and difficulties of growing coffee. Every piece in the store is made from fallen trees within the boundaries of Kerehaklu. Some of their home decor like lamps are made from the roots of the Arabica bush that have to be uprooted every year because of the white stem borer pest attacks that plague coffee growers in Chikmagalur and Coorg.

Stump lamp made by Rooted Objects.

Stump lamp made by Rooted Objects.

One of the biggest problems that coffee planters face is the white stem borer. It is only the Arabica plant and not the Robusta that gets affected.

Although Robusta does not have a very good reputation (known to produce lesser quality coffee), more and more planters and roasters are talking about how it’s creating value for them on and off the plantation.

While some planters are using Robusta as a shield around their estate to keep the white stem borer out, roasters are applying new techniques to extract unique and delicious flavours from the bean.

A lot of people drink robusta they just don’t know it. Most of these coffees are labeled as blends because the word robusta is being associated with an inferior variety. But that is changing. Robusta is now becoming more accepted in blends and some planters are experimenting with extracting flavours from plain washed robusta.

Recently my dad picked up 50 -60 saplings of a dwarf robusta varietal and we are experimenting with that. I’d like to pick up geisha or bouban from South America but logically this wouldn’t be suited against our topography, says Pranoy, from Kerehaklu. The history of robusta coffee on these slopes of the Western Ghats are more than four generations and some plants are nearly 45 to 50 years old. I believe there is potential to change the narrative of robusta through the stories we tell.

Coffee is a game changer in the beverage market. India is now the world’s 10th fastest growing market for specialist coffee and tea retail chains, valued at Rs 2,570 crore in 2018, says a report by market researcher Euromonitor International.

Demand for coffee is driven by millennials in urban centres, who look to experience different types of flavours. India witnessed growth in demand for gourmet and fresh ground coffee during 2016-2017.

Over the last decade the changing trends in the alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverage space have set some notes for this coffee wave. The increasing number of microbreweries in urban centers have set a unique stage for understanding the craft behind beverage production through tasting rooms, brewery tours and experience centers.

Ganga Prabhakar, owner of Coffee Mechanics believes that coffee in the Indian market will grow on the same parallels like wine, except faster. “Coffee is a very delicate crop to grow and just like wine we can see consumers demanding private label brands from particular single estates, grown and roasted for specific flavour.”

It’s also interesting to note that these coffee experiences give opportunities to be more quality conscious. Could this ripple off into the entire food chain creating more conscious consumers demanding better quality and ethically sourced food and beverage? There is hope and it could all start by appreciating a cup of good coffee.