It’s no secret that plastic poses innumerable threats to the planet (who hasn’t seen the Chris Jordan photographs, above, by now?) and makes up a shocking amount of our waste (about 85% gets sent to landfills, where it sits for up to 1,000 years, sending pollutants into the ground and surrounding water supply as it decomposes). And yet despite these risks, we’re still struggling to find a “friendlier” alternative to hold our single-serving yogurts, bottled drinks, and office lunches.

But researchers at Harvard’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering are about to change that with an often undervalued, undersized secret weapon of the sea: shrimp.

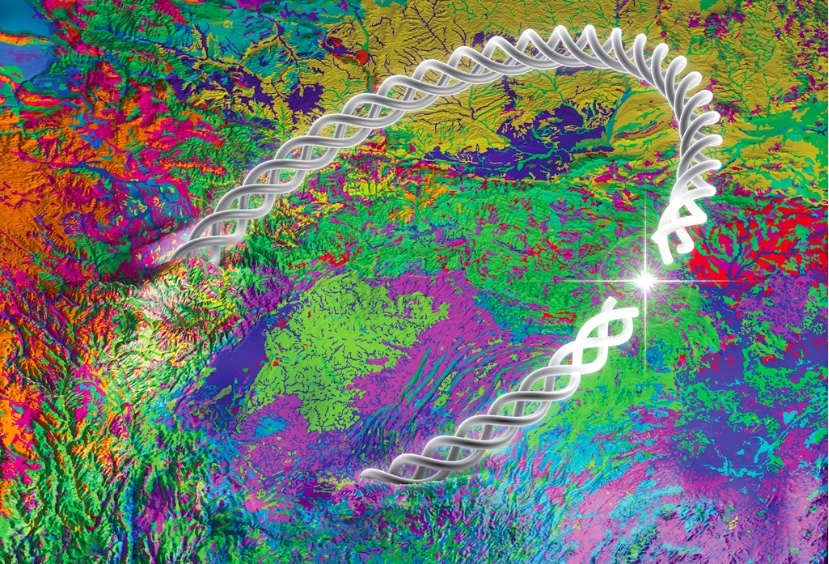

The Institute’s research team, led by Founding Director Don Inbger, M.D., Ph.D. and Postdoctoral Fellow Havier Fernandez, Ph.D., has created a fully biodegradable plastics alternative made from chitosan, a material abundant in shrimp shells. Chitosan is a form chitin, a natural polysaccharide that fortifies many animals’ exteriors, including insect exoskeletons and butterfly wings. “Besides vertebrates and plants, [chitin is] in almost every other living thing on Earth,” Fernandez explains.

The Harvard team processes chitosan in a way that allows it to be used in conventional plastics manufacturing practices. The chitosan is mixed with natural ingredients, such as water and wood flour, to improve shape, strength, and durability. Recyclable dyes and wax coatings add color and an additional layer of protection. This method opens the door for mass production of bioplastics that are as durable and commercially viable as the synthetic stuff we’ve been using for food ware and electronic devices for decades.

Chitosan isn’t the first alternative to disrupt the traditional plastics space, but it’s one of the most sustainable. Other bioplastics, like those made from cellulose and corn, just aren’t scalable for mass production and don’t fully disintegrate in the natural environment. Chitosan’s advantage is that it’s both plentiful and fully degradable. Over 150,000 tons of chitin are already being harvested as a byproduct of the seafood industry. Once it’s thrown away, chitosan bioplastics fully degrade within two weeks and release nutrients that support plant growth.

The Wyss institute plans to open discussions with manufacturers to address scaling and review FDA regulation of products and materials that come in contact with foods.

Photos courtesy of Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, Harvard University.