After double checking the address, a quick scan of the windowless warehouse did not present a clear entryway or confirm that I’d arrived at the correct location. Situated next door to a hulking structure filled to the brim with the remnants of a 75-year-old former steel mill, this tract of land in the Ironbound neighborhood on an industrial stretch of downtown Newark is incongruous to our standard vision for a farm. But as industry and consumers begin to grapple with how we might feed 9 billion people by the year 2050, sites like this will become an increasingly visible and urgent archetype of farming. After walking a bit further up the street, an abandoned lowslung brick building at the property line had a tiny sign confirming that I was indeed at the right location. Here at the site of a former steel-supply company, AeroFarms is establishing what will be the largest indoor vertical farm in the world based on annual growing capacity.

Top: Rendering of the future HQ for AeroFarms in development with RBH Group. Bottom: Current HQ warehouse building in Newark.

Top: Rendering of the future HQ for AeroFarms in development with RBH Group. Bottom: Current HQ warehouse building in Newark.

AeroFarms’ ninth farm is situated across from the train tracks in a working-class neighborhood that has a deep history of incubating industry. According to a profile in last year’s New Yorker, “In an average year, [the steel mill] shipped about 20,000 tons of steel. When the vertical farm is in full operation…it hopes to ship, annually, more than 1,000 tons of greens.” Since launching in 2004, the company’s three co-founders—David Rosenberg (CEO), Marc Oshima (CMO) and Ed Hardwood (chief science officer), have grown the company to 120 people operating sites across the Northeast. With their recent round of investment, the company is rapidly expanding with projects in development on four different continents in addition to plans in Camden, New Jersey; Southern New Jersey; and Buffalo, New York. What draws all these locations together is the way that AeroFarms has been able to repurpose industrial spaces into warehouses for their modular farms, bringing edible greenery and economic opportunities to urban centers that have been disproportionately impacted by global manufacturing.

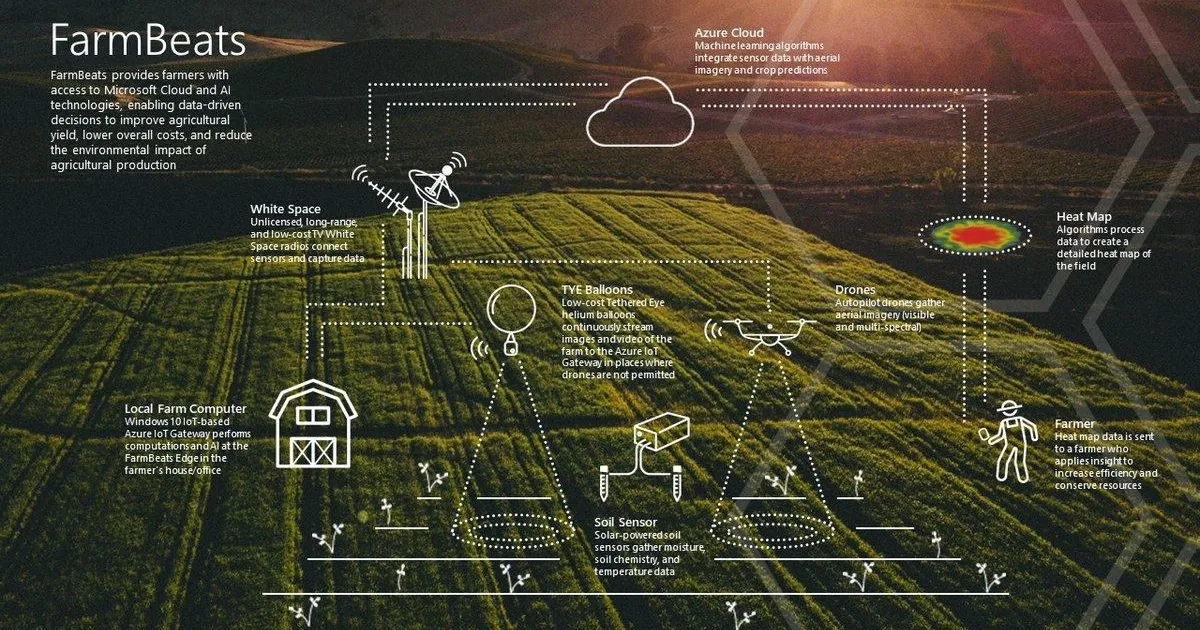

It’s this dedication to modular, local, scalable systems that is at the heart of AeroFarms mission. Unlike traditional land-based farming, productivity at vertical farms is measured by cubic foot, not square foot, and every input and output is precisely recorded through a combination of sensors that monitor the tightly controlled settings for temperature, light, CO2, humidity, airflow and nutrients. The data—AeroFarms’ growing trays collect 130,000 data points—is then dialed in in realtime by data scientists using machine-learning software to produce what AeroFarms calls its “growing algorithms.” Without seasons and the fluctuations of nature, the company has cut down their growing cycles from 30-45 days in the field to 12-16 at AeroFarms. And because the produce is harvested and bagged on site, the company hopes to bypass complex supply chains by growing and selling locally, often direct to consumers within 24 hours. When we were invited by AeroFarms’ CMO and Co-Founder Marc Oshima to tour the farm late last year, it was this holistic approach to operations and across the supply chain along with the company’s dedication to transparency that most impressed us. Below, are excerpts from our conversation and tour.

On AeroFarms’ Ethos

Marc Oshima: What makes AeroFarms unique is that we actually have patents around a lot of our growing technology, but we also have a lot of trade secrets. And so, it’s that approach that we’ve taken with intellectual property that makes us special. It’s a holistic approach. What makes us very different is that we brought this expertise all in-house. Everything you’re looking at is proprietary. We designed and developed it. It’s that understanding of our growing systems, the biology, the environment, and how we put that all together, that is so critical in terms of thinking about how we enable local production and bring the farm to the cities so that it’s really about feeding the masses.

We’re working closely with partners like Dell Technologies in terms of how we can accelerate what we’re doing with respect to the sensors and monitoring, and really think about how we replicate these things on these farms. We have a lot of tools in place that’s allowing us to do it faster, and in a more robust way. Our whole lens as a company is: how do we build more of these?

On Growing Algorithms

Marc Oshima: We’re going to go into one of our grow rooms. This particular farm and this grow room we’re in is optimized and designed specifically for short-stemmed leafy greens and herbs. As you can see, there’s different stages, different things happening within our towers, and you can see multiple varieties. You’re looking at different levels of products and different levels of maturity.

We monitor the environment like temperature and humidity through sensors. But there’s also custom reservoirs, so custom nutrients can be tailored based on what the plant needs. Lighting can also be adjusted—as you can see some towers are on and others are off. There’s data being collected in real time, everywhere, and our team has the ability to see on their handheld device that data gets assimilated, so that we know whether we’re producing the right conditions that we’ve designed for.

MOLD: There’s a lot of people milling about in here, so the system is being regulated on some level by machines and feedback, but, it still requires a human touch…

Marc Oshima: First of all, it’s biology, right? So you have some variability there. We use things like machine vision and machine learning technologies so that these growing towers are really like living computers. They’re constantly adjusting, as well. But the human eye, the human interaction, is also what makes us special. Our crop physiologists, plant pathologists and team members are looking and thinking about, “How do we create the right plant? The right environment?”

Simultaneously, we’re training our team on what to look for. We have over 280 different standard operation procedures about how to run a farm, so it’s very systematized. And, it’s based on our years of growing and our history.

On Deliciousness

Marc Oshima: And now, we can take it all the way back to the farm and the idea that we can stress the plant in different ways to optimize for that taste, texture and the nutrition. How can we replicate what’s in the soil while we look at the 17 essential elements a plant needs? To change the plants’ characteristics, we can look at the micro and the macro nutrients.

The difference is the level of control and precision we have here—we’re constantly monitoring the absorption rate of those elements, and we’re adding, based on each plant, each stage of maturation, what the plant needs. When we’ve done third-party testing, it’s a much more nutritionally-dense product, versus, the field grown product—both conventional and organic.

The nutritional density is because of that level of control and precision and, we can replicate it again all year round. That’s one of the exciting things from this, and it’s one of the reasons why we focus on short-stem leafy greens or leafy greens in general, as categories. You really wanna change the equation? A calorie’s not a calorie. This is more nutrition-dense. So, how do we have impact in communities?

On Designing Systems

Our company is really about taking best practices and understanding how to integrate them into systems. We really think of ourselves, not only as farmers, but as a capabilities organization, and how we can improve how we grow with control and precision. So, whether we have a farm here in Newark, Dubai or London, we have the ability to be able to look, in real time, and see what’s happening.

I mentioned we have 280 plus standard operating procedures. What’s so critical, and the reason why we think about large-scale is that we want to be able to support the right infrastructure from an operations standpoint, but also, food safety. We have QA Technicians looking at how we are performing against each of our different activities. We have Industrial Engineers as part of our team, looking at processes and understanding that.

And so, not only do we have horticulture experts who look at the plant health, but we also look at how it translates to human health so we have registered dieticians and nutritionists on our team. From the Operations standpoint, we have world experts in leafy greens and processing and facilities. So, this is, again, how we can bridge what’s called, “Good Agriculture Practices” and “Good Manufacturing Practices” and think about a new standard here.

We’ve brought all of that in-house because it’s so important to understand the symbiotic relationship between the environment, the biology and the engineering. We designed and developed all of this. Then we consider how we start to measure around the data safety. That really helps us optimize how we manage the build-out, capital expenditure, design, but more importantly, the operating cost.

For the team, there’s a shared passion and a shared purpose. We’re writing a new playbook in terms of how we can transform agriculture—and have an impact.