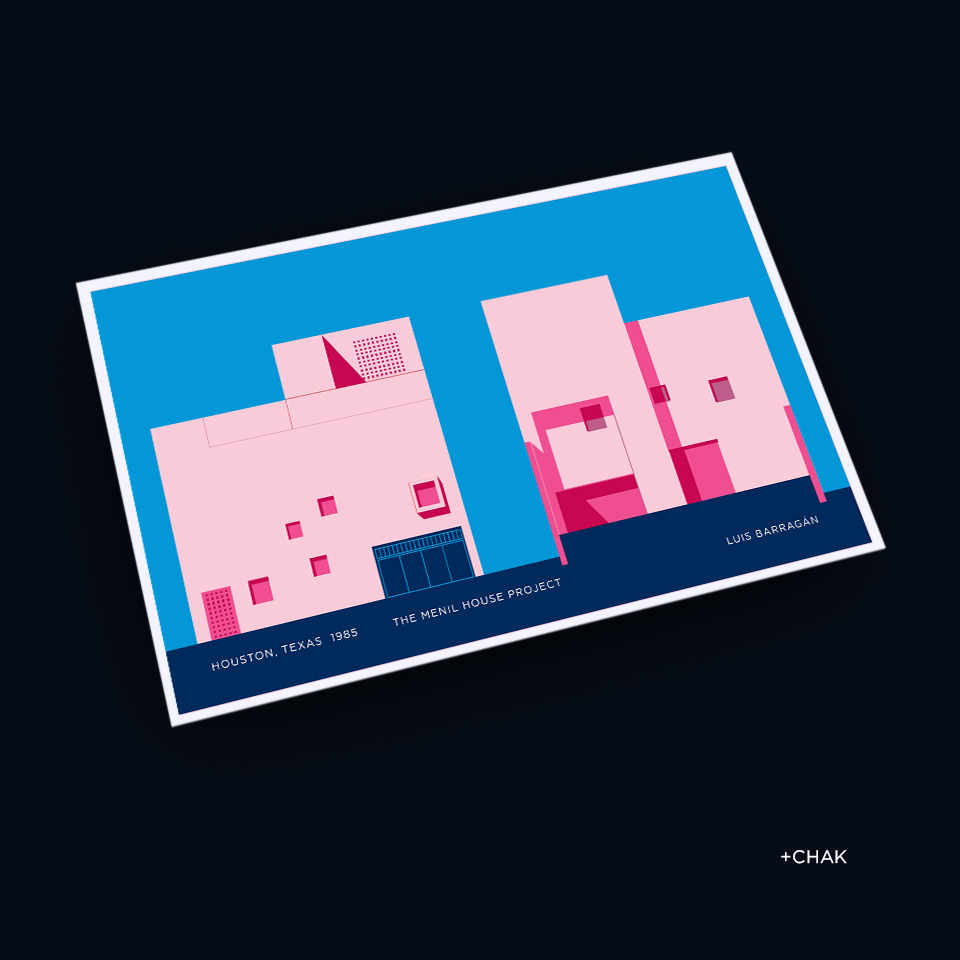

I met Chak ceel Rah Blancas outside of the Luis Barragán house in Mexico City, on the sort of January day where the sparse winter sunlight would just allow for moments of precious light to reflect on the inner and outer walls of one of Barragán’s personal constructions. Chak ceel has worked for the Barragán foundation in many capacities for many years, and so outside of this house, we naturally began to converse about ideas of light. Drawing from my background as a producer of architecture documentaries as well as from Chak ceel’s personal experience with K’iche Maya fishing practices, we exchanged thoughts on what information light can communicate about our built and natural environments.

Chak ceel linked Barragán’s work, specifically his approach to light in astronomy, textiles and serigraphic printing, to a greater inquiry in light that aligns with how the indigenous community of K’iche Mayans he is a part of determine ideal fishing conditions. But of course – the light that hits our seas, oceans and gulfs is influenced by weather, and temperature is directly influenced by light, all connected by phases of the moon, sun and stars. Contextualized against a larger commercial fishing industry, in which conditions are predicted and measured by machines like barometers (for pressure), anemometers (for wind), and accelerometers (for waves), a neglect of innate intuition is revealed that reflects a larger societal distancing from food production and sovereignty. And so, I wanted to hear more about this practice, which inherently makes more sense than all the machines that have since followed.

Corinne Mynatt:

We met in a place where light is a paramount consideration in the context of architecture, at the house of Luis Barragán in Mexico City (Barragán House). Can you tell us a bit about how light became of interest to you, as a thread through your work across disciplines, and via the heritage of your people?

Chak ceel Rah Blancos:

I’m from a small town of fishermen, Santo Domingo Kesté, where changes in the light and color in the sea give us a different understanding of the cosmos. Our ancient beliefs consider the landscape and its changes of colors to be sacred, to be protected from destruction. We notice and track the turquoise color of the sea, the blue of the sky, the different hues of the sunset. For many generations, my ancestors have kept this [practice] in their hearts with poems and through indigo pigment in their textiles. Also the observation of stars (astronomy) is another way to see light and its duality with darkness, literally and metaphorically.

CM:

Many people may think that fish-schooling or fishing patterns may be predicted through nuances of the weather, could you tell us more about how K’iche Mayan fishermen use light as their tool?

CRB:

In my opinion, elder, experienced fishermen are better at observing fish behaviour, the changes in the sea and how everything is connected. For example after the summer solstice, the sea becomes a red color because the plankton arrive; photoluminescent microorganisms appear at night during the equinox in March – we know that schools of fish are looking to eat them at this moment. This photoluminescent aspect is another tangential relation to the observation of light.

The cazón (Galeorhinus vitaminicus) baby shark is also a key symbol and tool used by the K’iche Mayan. There is one season where you do not fish cazón, because the females are pregnant. The word for shark in Mayan, xok, relates to the word x’ob onik meaning to count and understand, which bears this important relation to fishing. The cazón shark is [usually] cooked and eaten in tacos.

CM:

What are the cycles of light these fishing patterns align with?

CRB:

The solstices, the equinoxes and one event of light that only happens in countries or areas next to the Ecuador line known as the paso cenital. The paso cenital happens twice a year in May and July, when the sun is at its highest point, directly vertical to the earth. Elders an fishermen also note rainbows that appear at the beginning of the rainy season, and halos at the end of it that help define patterns of change. Other fishing cycles relate to the rain of stars, the alignment of the Milky Way and Orion belt, and the path of Ursa Major in the night.

CM:

Does anything particular happen at the time of the solstice?

CRB:

At the summer solstice the daylight is longer than other days and its position is in the north. The distance between the sun and earth has changed, therefore the temperature and the behaviour of animals, including fish, [have also changed]. Humans now wear clothes and cannot notice these nuances. Our K’iche Mayan people (and others that precede them), would have noticed the skin burning, the changes of light. Fishermen also notice skin burning – another way of sensing the light and its changes. Red skin is Mayan skin.

My grandfather told me that salt water is the soul of the sea, and that fishermen would not wash this [the salt] off, in order to protect their skin. These days people come out of the sea and wash themselves under freshwater showers – my grandfather could not understand this when he saw it.

CM:

What are some of the tools or techniques involved in using light as a fishing divination device?

CRB:

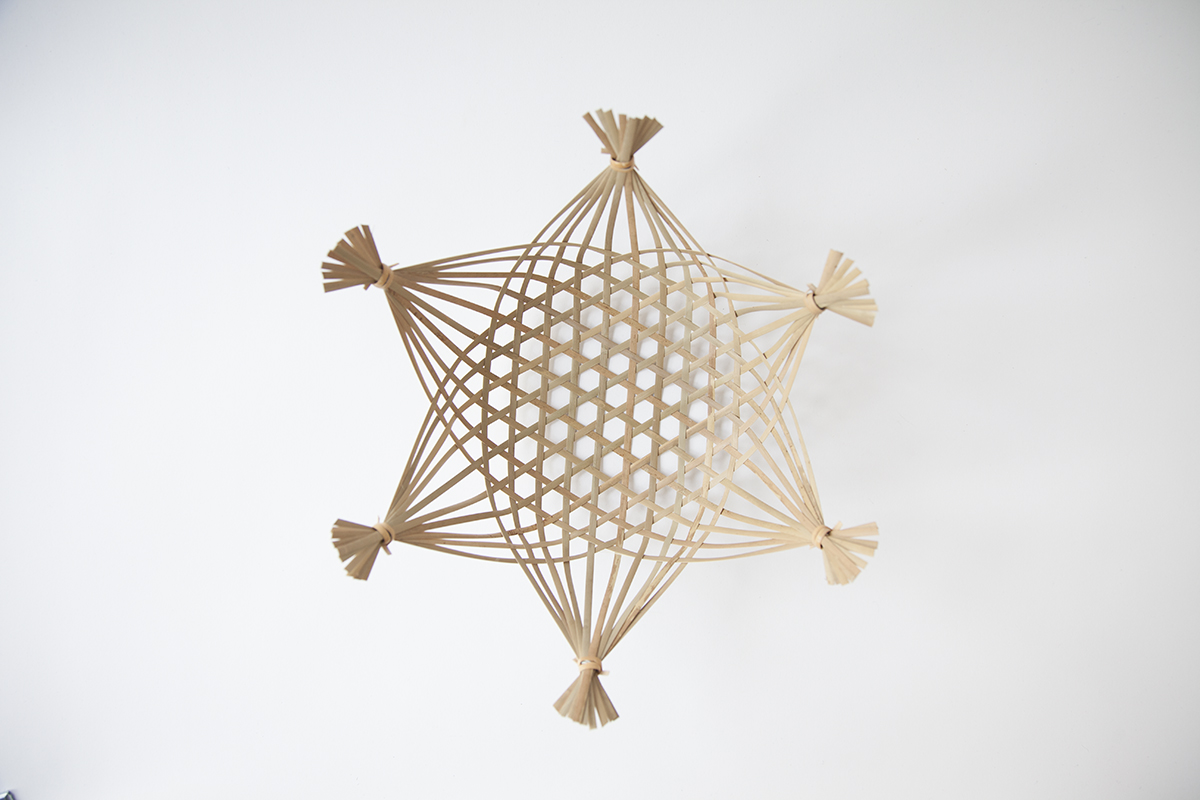

One tool is a branch from the cacao tree, with a particular triangular formation of branches. They use this to measure how the sun is moving on the horizon, used somewhat like an astrolabe. More generally there is the boken, a very particular measuring device for the phases of the moon, calculating days and years. Archaeologists have found these ancient counting bags from 5,000 years ago, with a specific number of seeds, with specific notes, which they know were used for measuring time. You can also actually eat the flowers that the seeds produce (colorin from the tzite tree), which we prepare and cook, but eating the seeds themselves will make your stomach hurt. For fishing itself, fishermen would use termite eggs or small fish for bait, and particular baskets made with straw and cane, much better than plastic ones used today.

CM:

Could you tell us more about food culture in relation to the fishermen?

CRB:

One thing that comes to mind in particular is the daily food that fishermen eat and share with their families. As a child I remember eating the catch of the day – such as sardines or other white fish – wrapped in banana leaf with jicama, and either steamed or grilled over fire. But the diet is changing. Now I fear fishermen may even be eating sandwiches for lunch on the boat. And for example avocados used to be known as ‘the butter of the people’, because it was inexpensive and provided fat, but now it is more expensive and food culture is changing.

CM:

How is the practice of fishing by monitoring light conditions still used today, if so?

CRB:

We still say today that during the hurricane season the sea changes to a red color, the reflections of color at sunset are more evident in the sea at this time. In July for example the sunset color is more blue than orange, which also causes a particular refraction of light in the sea, where the illusion of xokla or mermaids is said to have originated. Xokla relates directly to the Mayan word for shark, xok.

At hurricane season the clouds are different because there is a smaller portion of water in the sky. As I mentioned the photoluminescent microorganisms are also key – we know the fish are coming for this when they appear, so it is a good time to fish. And again the shark – when you don’t see the shark, this also correlates to the color of the sea changing.

CM:

What is the role of oral history for the K’iche and how has it been passed down?

CRB:

Some Mayan leaders created beautiful myths about the solstice, for example. This wisdom was transmitted through symbolic colors in textiles and weaving, and through riddles such as “what is the dream of rivers or lakes” and in lines of poems such as “the clouds have the color of rain”.

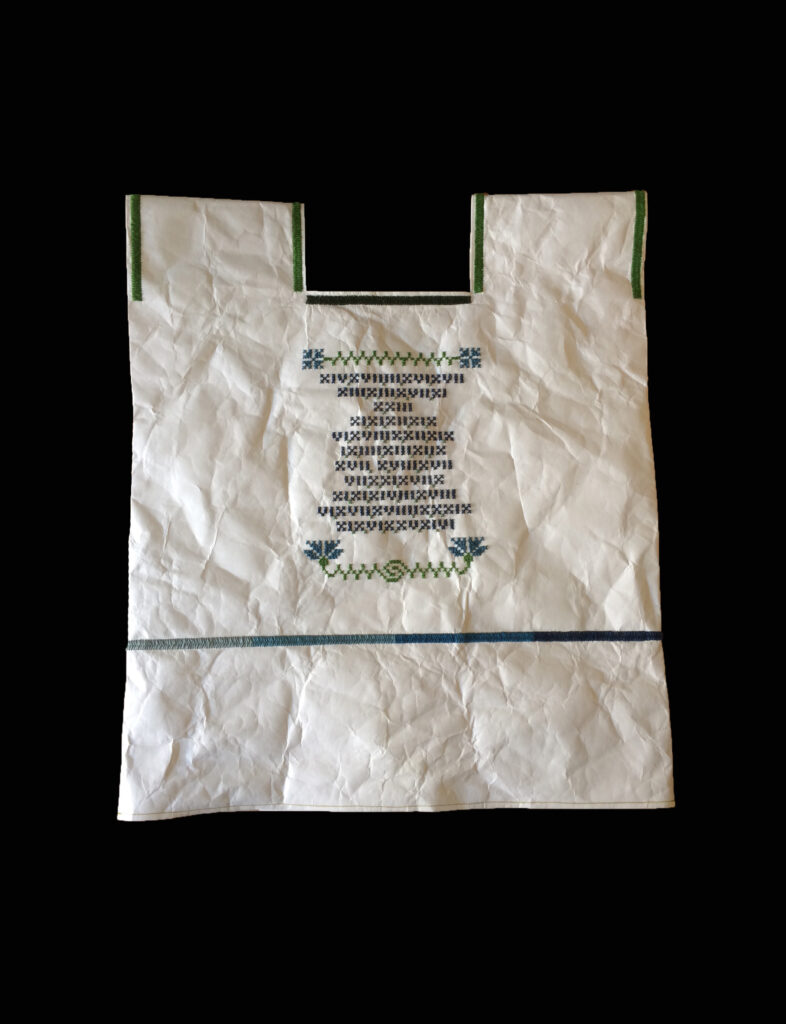

In relation to my work in textiles, and research into indigo, I know that weavers use these stories in their embroidery. [They’ve used] textiles [to] talk about how the sun and moon move in the sky – the first ‘fashion design’ for us was connected to movement and phases of the moon, sun, and the different reflections of light. This is how some knowledge was passed down.

CM:

What comparisons do you draw between these fishing practices using light and other practices such as architecture, design, agriculture, astronomy, textiles, poetry?

CRB:

Cosmos – the world we know – has an order or chaos. How we react to this is what builds our personalities and the way others see us. We need these interactions with others to understand that there are moments of light and shadows in creative processes, love, work, life cycles etc. We call this the nomak and mah in Mayan. In new age culture it is called the Mayan yin and yang, though the concepts have differences. A greeting that embodies this from the Mayan language is ‘is there light in your soul’, also translated as ‘is there blue color in your soul’(¿Jas kub’ij k’ux la?). This is how we say hello to each other, and says a lot about the K’iche Mayan ethos.

Chak ceel Rah Blancas is an engineer, textile artisan, and visual communicator. He has worked and studied across the world, from Mexico to Japan. His experience in graphic design led him to collaborate with UNESCO’s World Heritage program about permaculture practices throughout Mexico, with a focus on the traditional and ancestral cultures of different indigenous peoples. His current design work incorporates distinct cultural references to the K’iche’ Maya people and their tradition of creating textile patterns based on different agricultural events.

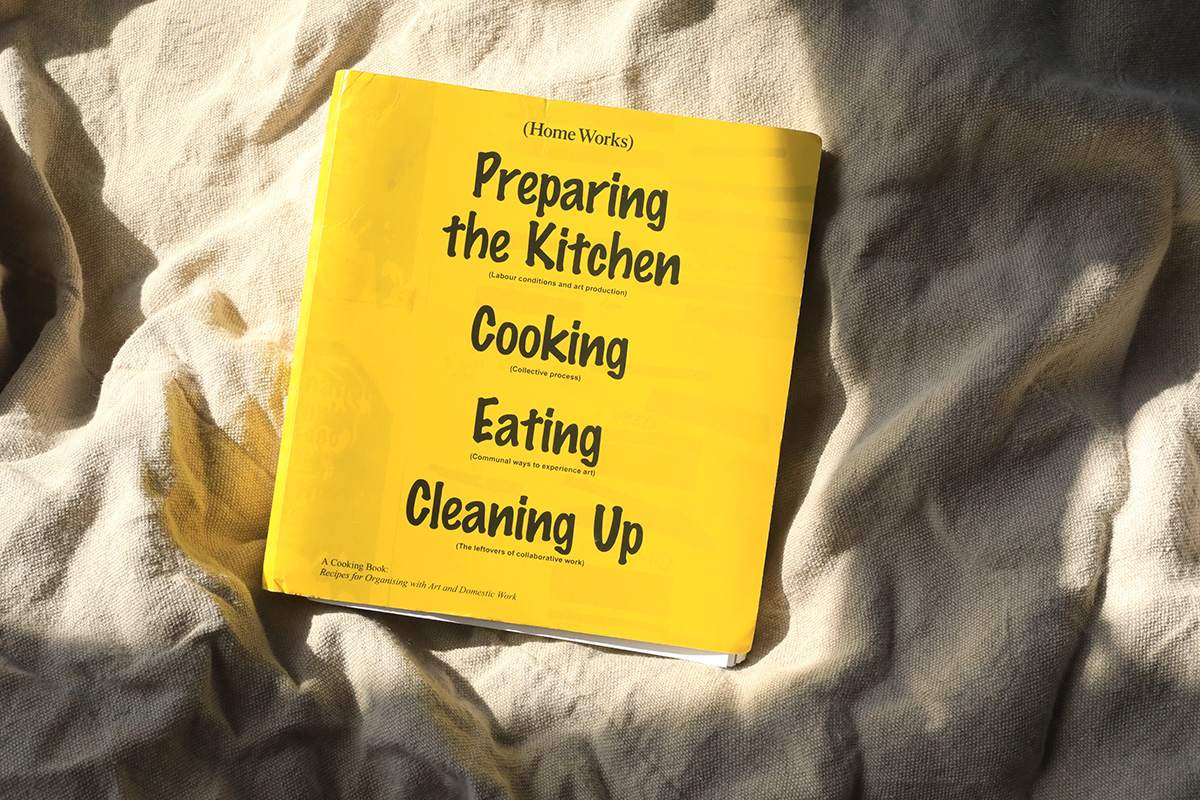

Corinne Mynatt is a curator, writer, consultant and producer. Her work covers transdisciplinary practices across art, design, architecture, food, and technology. She has a particular interest in food and design as mediators of culture: her book Tools for Food: The stories behind objects that influence how and what we eat was published in autumn 2021. Recently she worked as Producer for two architectural documentaries particularly focused on light, filmed in Sri Lanka and Mallorca about Geoffrey Bawa and Jørn Utzon respectively, directed by Clara Kraft Isono.