Walking down the supermarket aisle you may not register them at first. Small and innocuous, these H.R. Giger-reminiscent figures have infiltrated our bread and produce sections, clinging tightly to the plastics that contain our groceries. They’re plastic bread tags—a simple design solution that is ubiquitous to the supermarket experience. Often overlooked, one organization, the Holotypic Occlupanid Research Group (HORG), has become a champion of the object, bringing the “species” into new light through careful documentation and categorization of the various types of bread tags that can be found in supermarkets across the world.

HORG was first formed in 1994. John Daniel, the institutions’ founder and current Director of Public Outreach, recalls becoming fascinated with the specimen after finding one wedged between the creaky wooden floorboards of a friend’s San Francisco Victorian. “These objects that you use every day, they’re literally designed to fall below the radar of your perception,” he tells me, “Whether it’s straws, traffic cones, or pens — sometimes you take a closer look and think, ‘Wait a minute, what the hell am I looking at.’”

Once he started looking, he couldn’t stop. John started seeing the plastic tabs everywhere, and with this newfound attention, noticed an abundant variety of sizes, shapes, and colors. John, who is a visual effects designer and has worked on movies like Matrix Reloaded and Star Trek, was drawn to the the plastic tabs because of their biomorphic shapes, “[I’m] someone who was previously really obsessed with invertebrates and any organism that is ignored or unloved, and to me, this looked a little like a parasite. I was obsessed by that.”

For John, the initial intention for founding HORG was a tongue-in-cheek attempt to poke fun at the politics of classification, a parody by a taxonomy-lover for taxonomy-lovers, “I thought it would be really fun to try to make a taxonomy of something that is literally an industrial item that is, you know, not a real organism.”

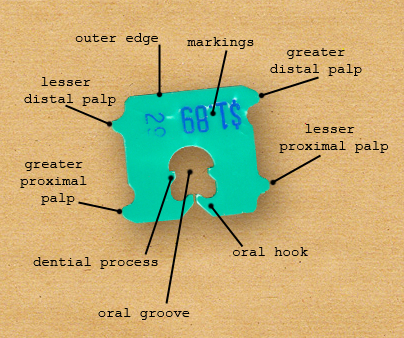

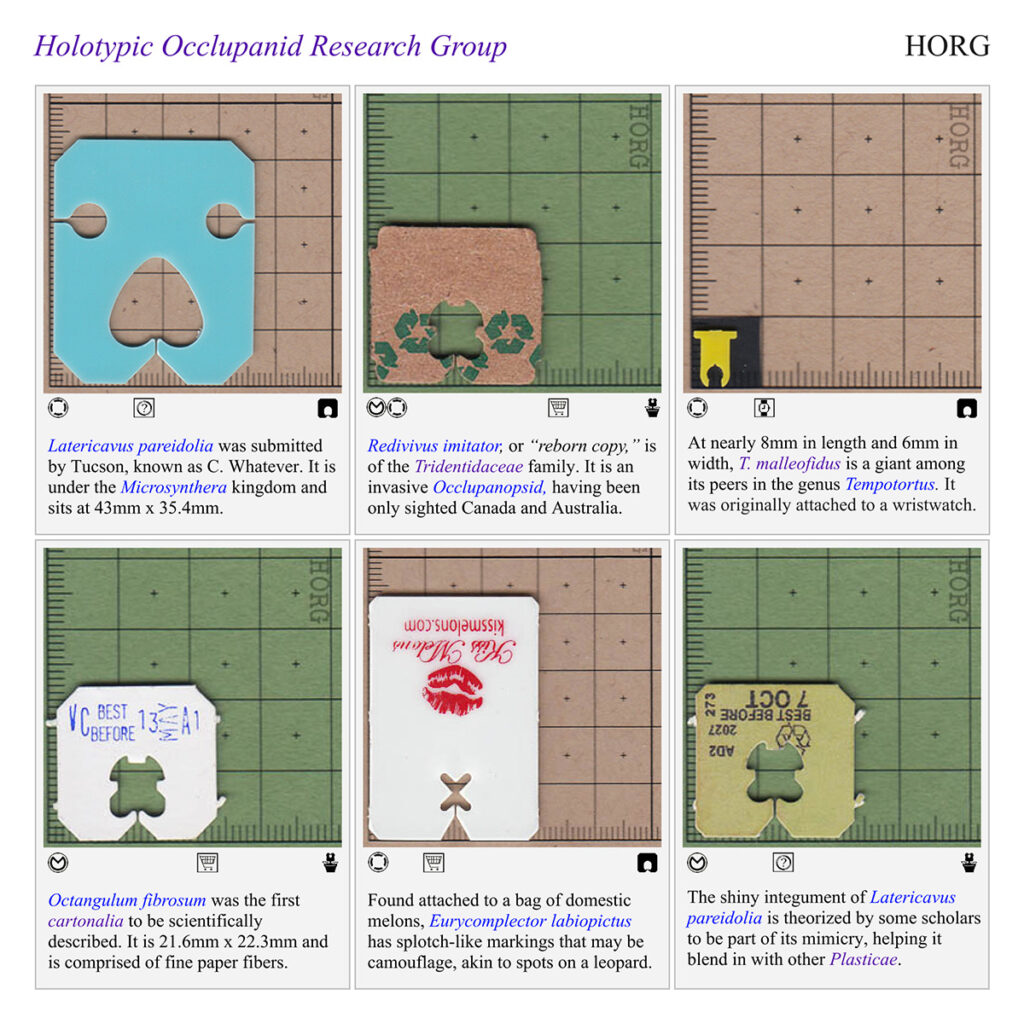

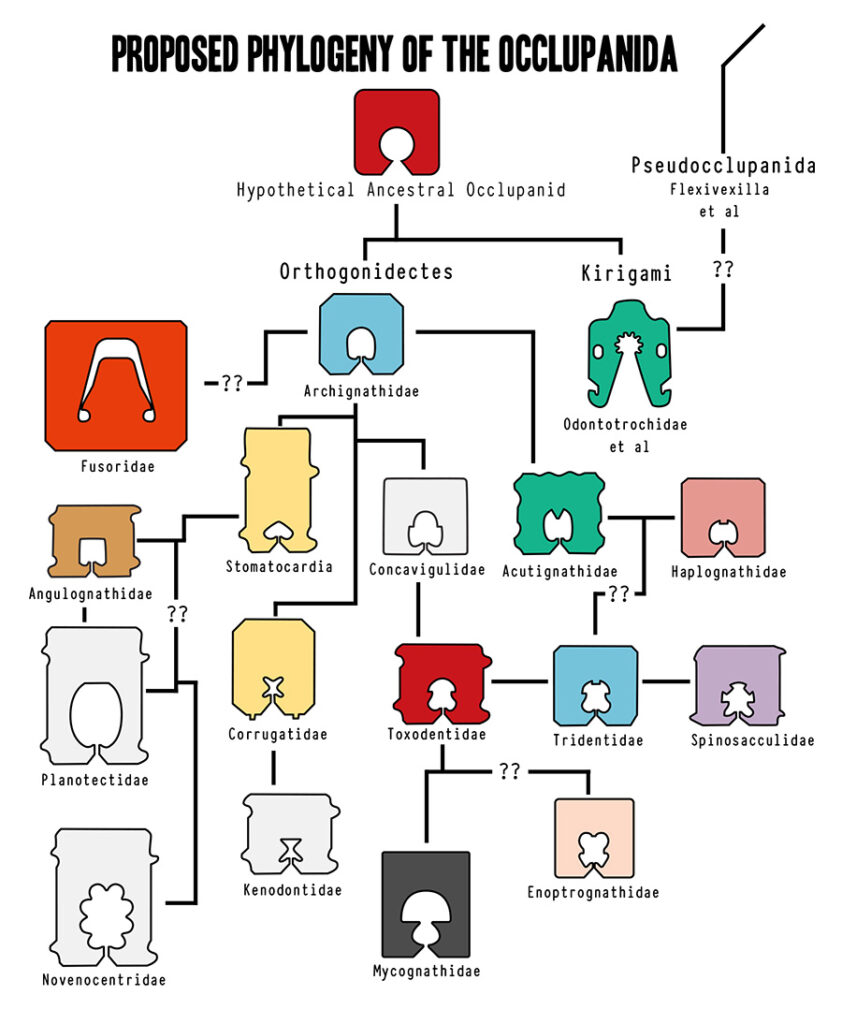

Thus began what the HORG website calls, the formulation of a synthetic taxonomy, one that forgoes traditional factors such as genetics, derived traits, growth and development, sexual dimorphism, reproduction, or fossil record, in the naming process. Occlupanids, the scientific class for plastic bag tags, are placed under the kingdom Microsynthera, of the phylum Plasticae. In order to arrive at this categorization, HORG followed in the tradition of Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy, grouping specimen together due to their shared characteristics, and according to the website, just winging it, “The concept of species, like real species that are living things, is a construct, right?” John tells MOLD, “It’s the thing that we’ve applied to a continuous thread of life.”

John first became interested in the thorny complexities of taxonomy while working on an art project as an undergraduate sculpture student at UC Santa Cruz. While researching a diagram of a homolozoan, a prehistoric invertebrate, he had sourced as reference for the piece, he discovered research papers of taxonomists arguing about the correct categorization for the species. “People were really angry,” he remembers, “It was from these scientific journals in the 1800’s, and people were just taking it incredibly personally. And all this passion over this tiny thing really struck me.”

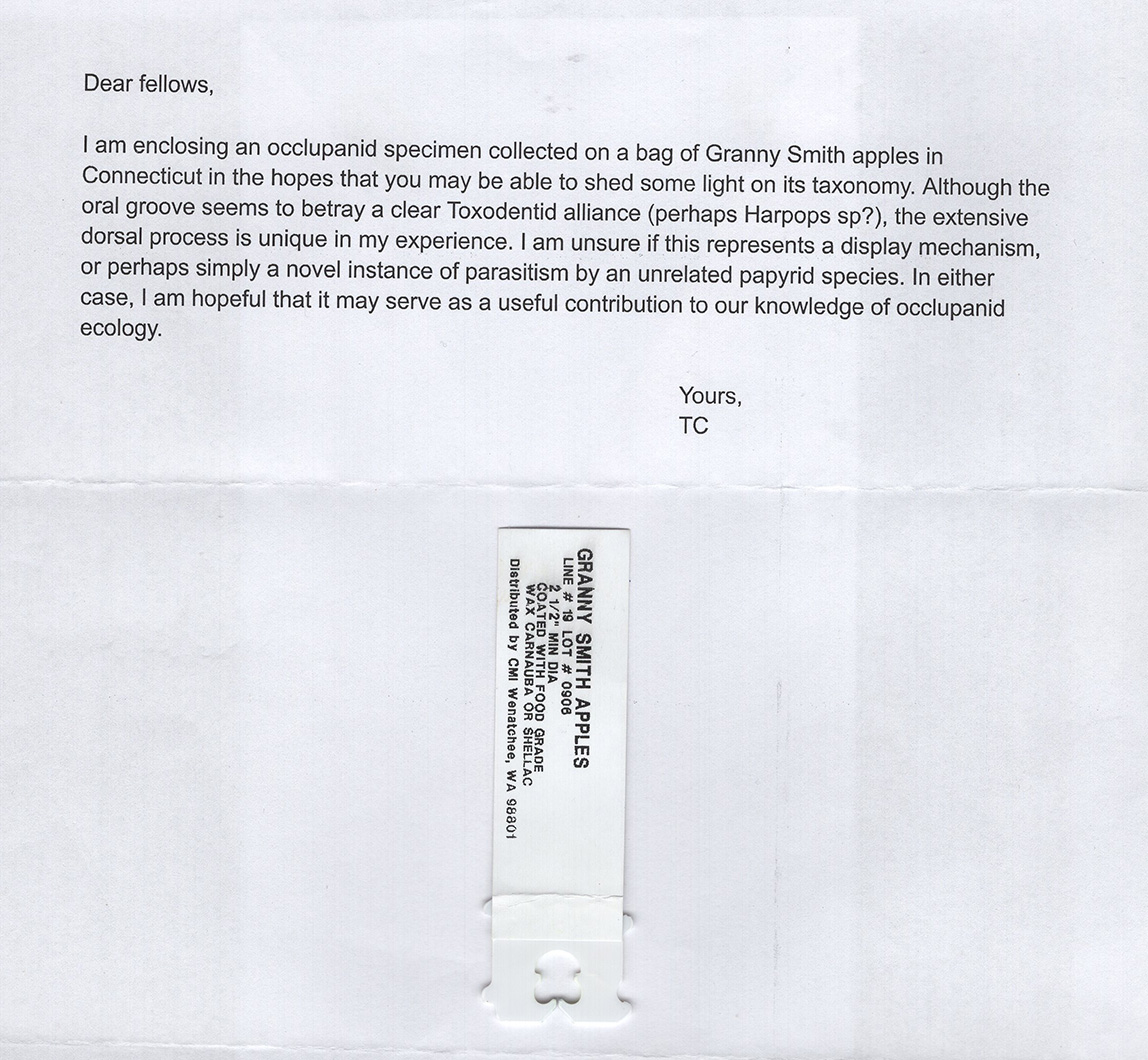

The word occlupanid is drawn from the Latin verb occludere, which means to close, and pan, or panis, which is the Latin root for bread. Since the institution’s founding, HORG has documented over 270 of the specimens. HORG’s classification system categorizes occlupanids according to the shape of their oral groove. There is the expansive Archignathidae family, whose simple, spade-like groove makes it one of the most commonly found in the wilds of supermarkets across the world. Or, if you’re looking for something more funky, there is the distinctive Novenocentridae family, whose name means “nine points”, and is used to describe the nine “sharp dental processes” or petals that form the specimen’s large, tree-reminiscent oral groove.

The origins of the bread clip can be traced to a man named Floyd Paxton. In 1952, Paxton was on a flight enjoying a complimentary packet of airplane peanuts when he realized that—in the case that he wanted to save his snack for later—there was no effective way to re-seal the package. A manufacturing engineer by training, he quickly prototyped what would become the bread clip, carving the shape out of an expired credit card with a penknife.

For Paxton, who was from Yakima, Washington, packaging was part of the family business. Prior to World War II, when Paxton and his father shifted focus to producing nail machines, the father-son duo had produced items like the nails used to secure wooden boxes for transporting fruit. Although the plastic squares are best known for being used to secure supermarket bread loaves, they were first used by local fruit-packers on the West Coast, who asked Paxton to further develop his invention to seal plastic bags of apples. This eventually led to his founding of the company Kwik Lok in 1954. In this case, Paxton’s spur-of-the-moment solution spawned an empire. Today, Kwik Lok continues to be one of the primary manufacturers of bread clips in the world, producing billions of plastic clips a year.

This history, of course, is something that HORG chooses to skate over. “This whole idea of companies and manufacturers is outside of the purview of the science of occlupanology,” jokes John. In contrast, HORG defines occlupanids as naturally occurring parasitoids that “take nourishment from the plastic sacs that surround the bagged product.”

That being said, the framework of HORG’s phylogeny provides a handy tool for understanding the design history of the object itself. For example, a diversity of occlupanids in Europe, and particularly the Netherlands, might be attributed to a lost patent dispute in international court that allowed for European manufacturers, like Kwik Lok’s primary competitor Schutte, to produce their own versions of the bread clip. Or, the seeming dearth of occlupanids in certain geographies, like Central America, can be tied to the regions’ high humidity levels and the resulting preference for aluminum twists as a more air-tight technology for securing bags.

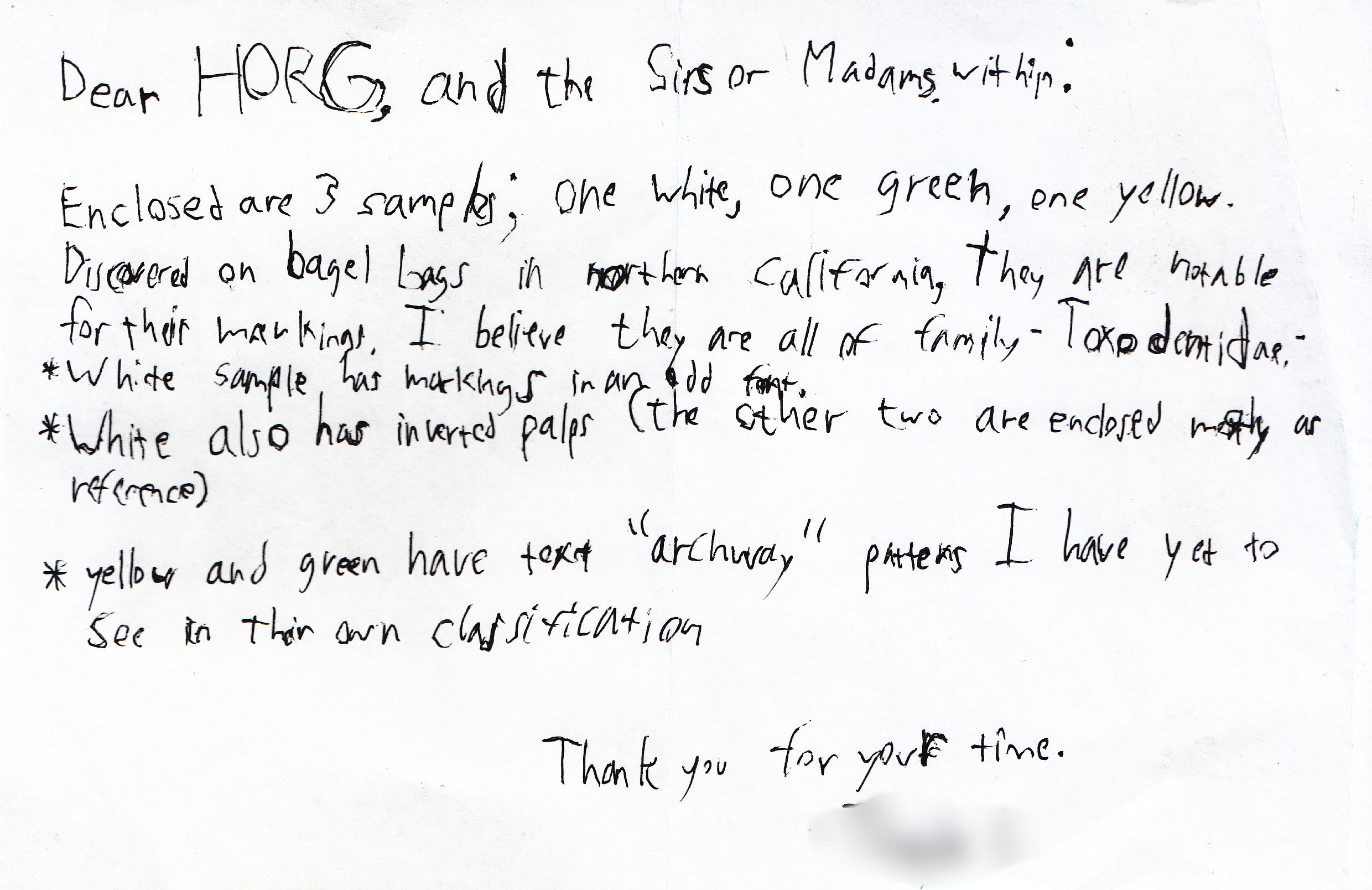

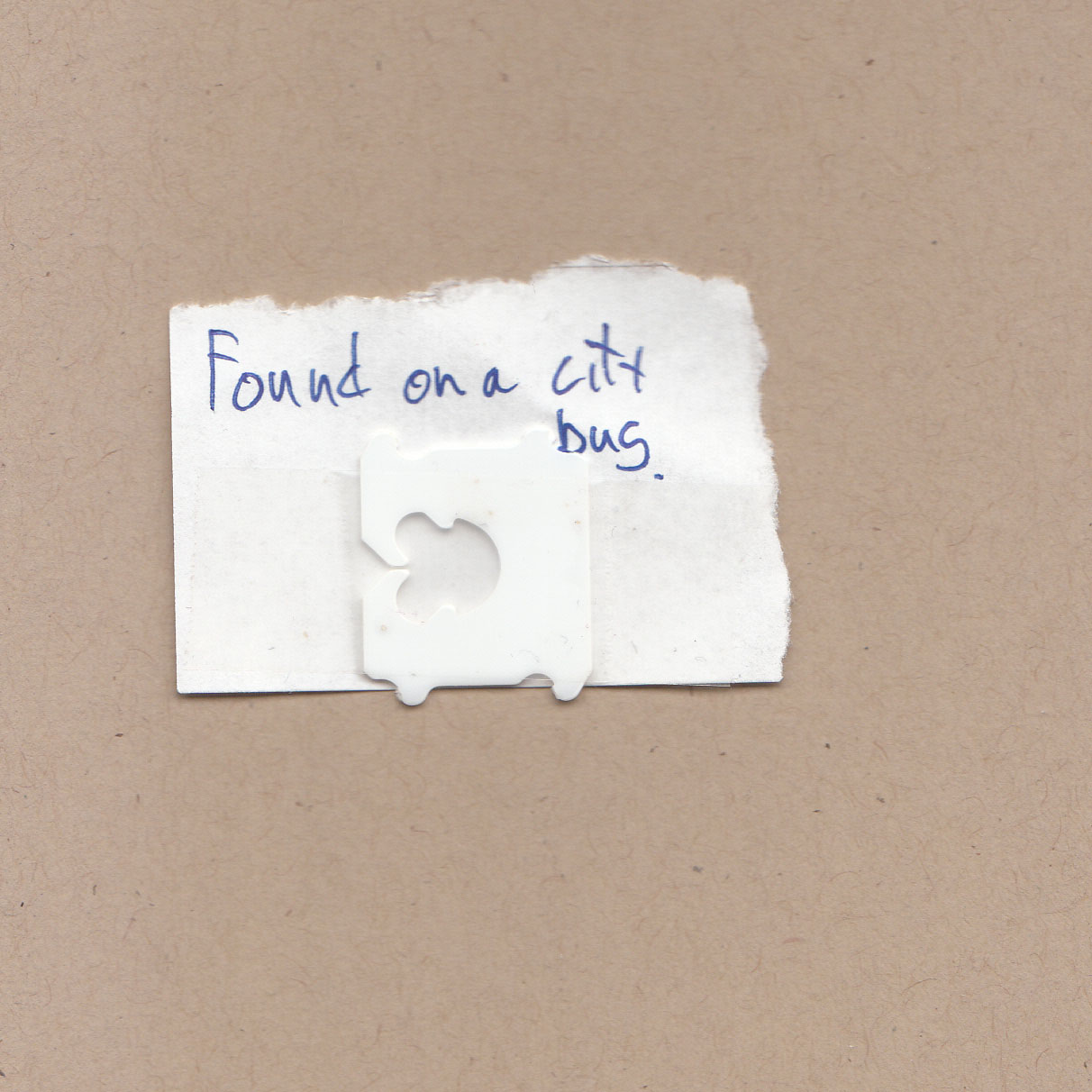

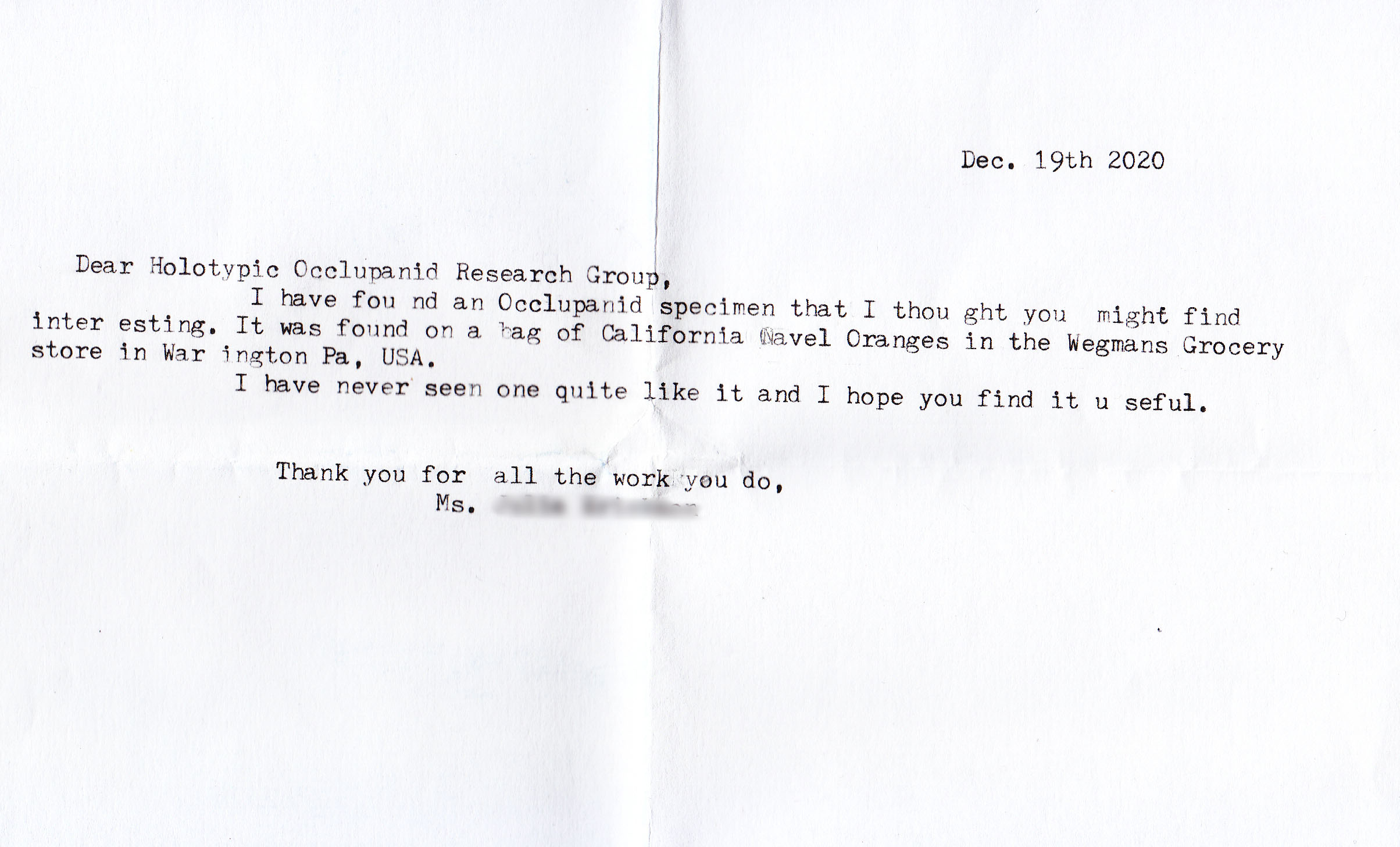

Most of HORG’s initial specimens were collected by John himself. However, since the early aughts, the organization has received submissions from all over the world. As HORG’s collection has expanded, so too has the community around it. In the subreddit r/occlupanids, almost 3,000 members regularly share their own collections and displays, even posting their own specimen for identification. Within these threads, heated taxonomical debates—much like those that first inspired HORG— can often go down. In a move that further cemented HORG within the broader cultural conversation, a collection of occlupanids was presented as a part of an exhibition held at New York City-based “modern natural history” museum, Mmuseumm, in 2018.

However, according to Daniel, the crowning achievement of HORG has been the inclusion of their methods of classification within a peer-reviewed medical journal. In 2011, Dr. Bruce Ragdale brought the field of occlupanology to the attention of the greater scientific and medical field in his study, which analyzed the medical effects of ingesting bread clips, and how doctors might be able to use the phylogeny introduced by HORG in their own diagnosis and treatment. “The real wonder is, here is a site that is playing at science that is now part of a real paper that [in its inclusion of a synthetic taxonomy] is playing with humor,” says Daniel. As HORG’s taxonomy continues to be utilized by scientists, taxonomic enthusiasts, and supermarket-goers alike, it’s become clear that occlupanids are here to stay.