In the 1960’s the enormous nutritional and sustainable potential of the blue-green alga known as spirulina was rediscovered by western science. It’s potential as an easy-to-grow food resource the Kanembu people of central Africa and even the Aztecs knew long before. Today, it is speculated that spirulina possess antibiotic properties, lowers cholesterol and blood pressure, is suspected to help prevent cancer, and contains an abundance of vitamins and protein—it is a superfood if any food deserves that distinction. Its benefits plus the ease with which it can be grown has made it among the foods to be considered for cultivation on Mars. So many are its benefits that it has been lauded by the World Health Organization, UNESCO, and the UN to be among the most ideal food for our species.

Surprisingly, here on Earth, raw spirulina remains a largely untapped nutritional resource. While it has been industrially produced since the ’70s, you’ll most likely find it relegated to the vitamins and supplements section of your local health food store in the form of a processed supplement. The potential of this incredible alga inspired designer Anya Muangkote to create the Spirulina Society system: an open source model for growing raw spirulina at home. Spirulina Society provides a blueprint of how spirulina can be effectively grown and eaten in most homes, and might be a more sustainable model for food production in a world of increasing food insecurity. Begun while Muangkote was pursuing an MA in Design Products at the Royal College of Art in London, the system also demonstrates that the carbon-eating alga can be an accessible alternative to our reliance on the unsustainable food supply chains.

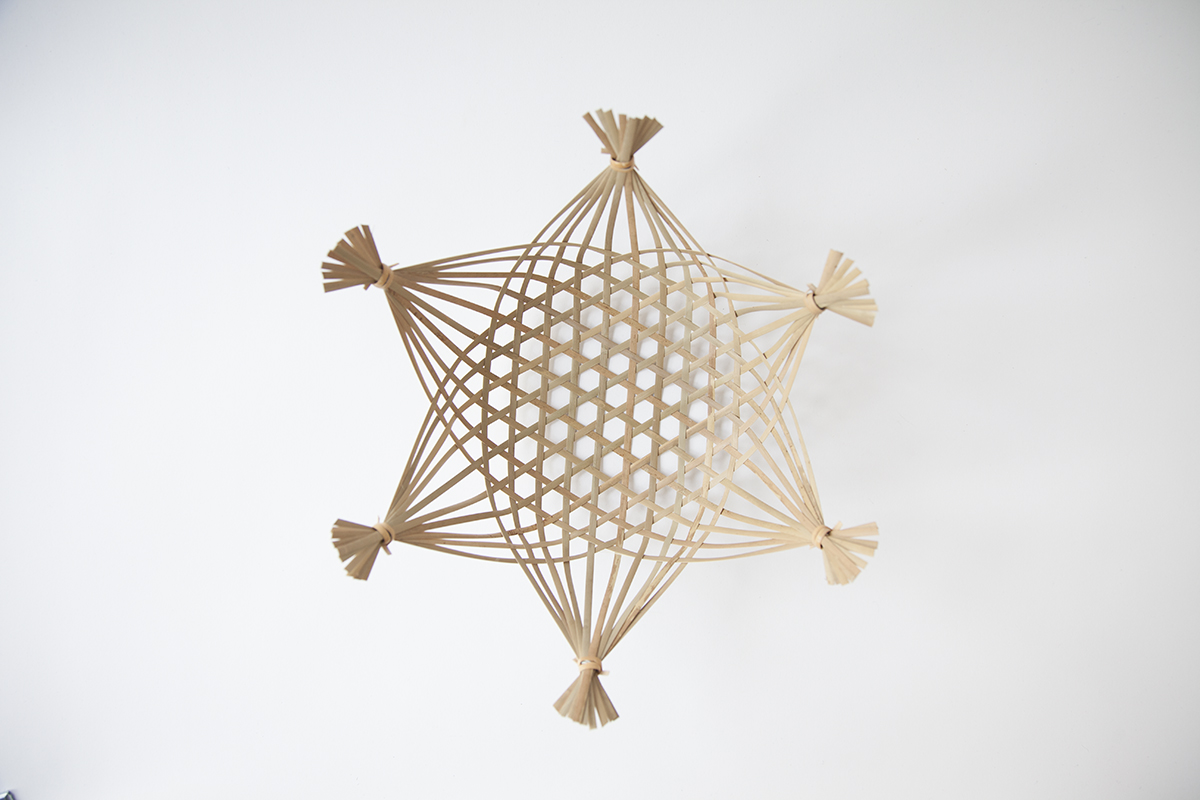

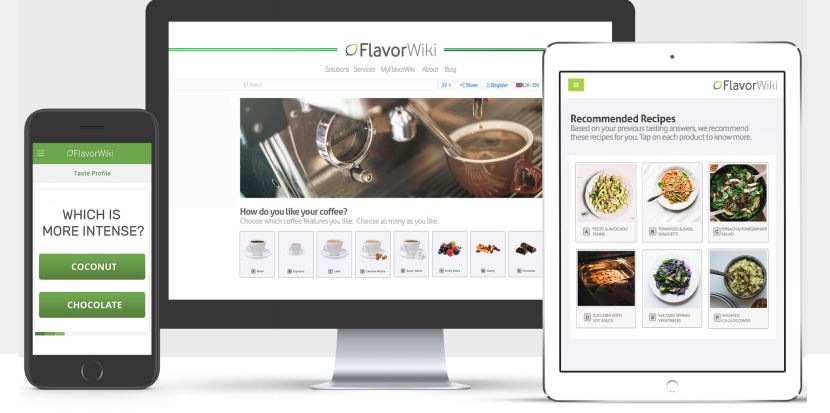

“I think raw spirulina could be and should be available for everyone everywhere.” says designer Anya Muangkote. “It’s still pretty much exclusive because it’s not widely accessible yet.” Beginning as a design research project, Spirulina Society lays out its instructions for using affordable and sustainable materials to build a home bioreactor (algae-growing vessel). Avoiding the opaqueness and rigidity of a product designed end-to-end, Spirulina Society is open-source, freely offering all the information and resources anyone might need about spirulina farming, from building a spirulina bioreactor to suggestions of how spirulina can be prepared for eating. The Society keeps the whole process digestible for most people so long as they can get their hands on a live spirulina culture and have access to a 3D printer (both resources that the website can help you find).

In Spirulina Society’s step-by-step process—one that Muangkote is continuing to perfect—the user is shown the engineering of the self-contained spirulina farm. The process, and even the parts used for the bioreactor, are highly customizable—Spirulina Society acknowledges this and makes its walkthrough guide both a manual and an assessment guide for what material and spaces might be best for growing spirulina in your own home even if you only have the space of a small city apartment.

The information Spirulina Society offers is exhaustive, but provides users with the most direct way to get things set up, “Showing the entire process also makes this less daunting; I wanted to create an inviting environment for anyone who wants to start growing Spirulina and consume it raw.” says Muangkote.

Eager as one might be to start cooking up some alga, to get started as a spirulina farmer still requires some commitment. The process requires and encourages a change in thinking. Aside from the many nutritional benefits of spirulina, Spirulina Society also highlights the idea that many people need to rethink food production and consumption. The climate crisis and resource scarcity are intertwined—and the mode of food production for many nations is critically unsustainable. While there are ongoing efforts to distribute spirulina at a wider scale around the world, Spirulina Society takes a hyperlocalized look at changing food production and consumption.

“It’s not just a project and I wouldn’t call it an ultimate solution either.” says Muangkote. “If it can at least create a conversation, leading to the public gaining an in-depth understanding of the purpose of doing this, that could then lead to behavioral change not only with just consuming [and] producing food but also with other things in general, that’s what I really hope to see in the future.” Perhaps not everybody will have the patience or be able to find all the materials required to build a Spirulina Society of one’s own, but for those that can, they may become part of the knowledge-sharing network Muangkote’s project aims to build. With the tools Spirulina Society offers, it can be as easy as sending a link, showing off your DIY’d bioreactor, or even sharing a plate of spirulina toast with some of your friends and neighbors.