Korea’s agricultural practices have modernized exponentially in recent decades, but on the tiny island of Jeju, where one third of its 1,900 square kilometer surface is jam-packed with 38,000 family run farms, it’s not surprising to find many of these generations-old farms continuing to utilize antiquated hand tools to navigate the small spaces where giant industrial machines have no room to tread.

On my most recent trip to visit my mom (a Seoul native, California immigrant who relocated to Jeju at the start of the pandemic) I noticed a neighboring farmer using a variety of hand-woven tools that I had, until now, only seen in museum displays. Wanting to learn more, my mom did some digging and found us this gem:

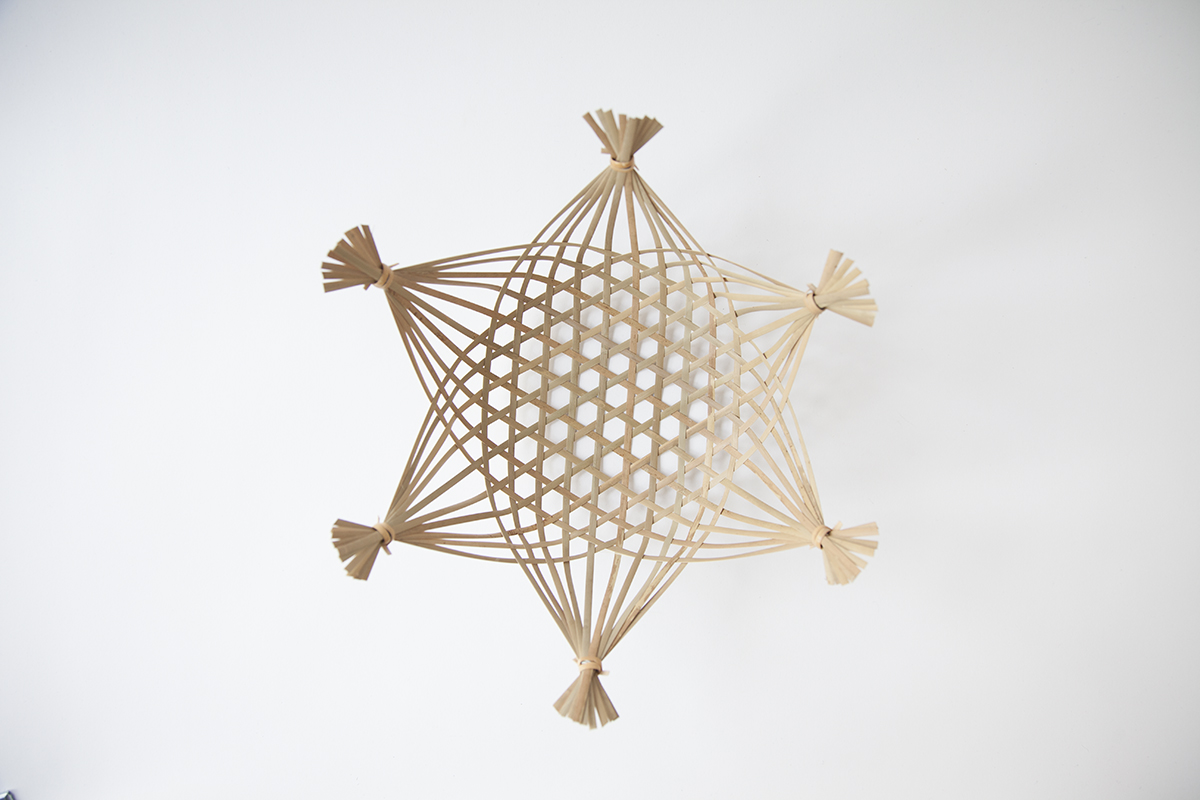

Kim Seok-Hwan is one of the last makers of hand-woven baskets from the long grass-like blades of shinseoran, a variety of Phormium tenax (New Zealand native, popular in landscape design) which was introduced to this slice of the hemisphere in the 1930s and, in Korea, can only be found on Jeju Island.

Mr. Kim specializes in making baskets known as mangtaeggi that farmers wear like a purse to carry the seeds that they disburse onto their fields by hand. He learned how to weave a variety of tools when he was in grade school—”it’s just one of the many things kids were expected to learn and I discovered that I was good at it,” he explained—but stopped as he entered mandatory military service and the workforce as a postal agent, thereafter.

Upon retiring, Mr. Kim took over a small rice shop in the old town of Moseulpo in the southern region of Seogwipo City. Through a combination of nostalgia, a small but sustaining demand from local farmers, as well as his concerns over a dying tradition, he decided to rekindle his craft under the only other artisan of shinseoran weaving at the time, Mr. Huh Se-Ahn, who has since passed.

Our journey began when my mom and I got into a taxi to make the trek to find Mr. Kim. The surly driver was in no way subtle about how irritated he was at having to drive us so far (mom lives in the northern area of Ae-wol), but when we began explaining the purpose of our adventure he, a Jeju native, slowly began to unspool a rich history lesson on the origins of the craft. He explained that wild shinseoran used to grow in abundance but has become harder to find with so much of the island becoming over-developed in recent times. He spoke the entire 45 minute drive as we feverishly nodded our heads (“nehhhh-neh”) and even got out of his car to join us in inspecting the shop once we had arrived.

Mr. Kim’s story has seen some media light over the last decade, but he seemed surprised that us ‘Americans’ had had enough interest to seek him out. As if on cue, he sat on his stool, picked up a basket-in-progress and began to show off his skills. He wet his hands with water, grabbed a few strands of dried grass and twisted them into a tight clean rope by rubbing them together with his leathery palms, then seamlessly wove them into the piece. “Back in the day, you know, they didn’t use water. They would spit into their hands to moisten the grass… but not me, my pieces are clean!”, he proudly jokes. We all laugh. His wife rolls her eyes. End scene.

The storefront is microscopic. To the left there are bags of rice stacked precariously on top of each other with specialty grains being sold in repurposed plastic water bottles. To the right is a small shelving unit that haphazardly displays his few remaining pieces: some mangtaeggis, grain scoopers, and miniature replicas of other traditional tools such as a “ki”, a winnowing basket that’s interfused with many shamanistic symbolisms and rituals. His inventory is often depleted, he explained, because at age 85, it takes him much longer to make a piece (up to two days for each). He still worries that no one will be left to carry on the tradition despite his efforts to teach workshops and find a younger audience, so he carries on a stalwart commitment to continue weaving even though his calloused hands and craggy digits look like they’ve long been in need of retirement.

In between his wife hilariously carpet-bombing him with criticisms,1 he cheerfully spoke to us the entire time in a partly indecipherable Jeju dialect while smiling with his entire face. I purchased three items (he gave me a small discount despite my dramatic protests), and as we left we implored him to stay healthy and to keep his wife happy so that we could continue to visit and learn more from him in the years to come.

- 1. Jeju women have a long-standing reputation as the fiercest of all Korean women. This stems from their sociocultural roles as hard laborers and impassioned guardians of the land and sea (e.g. our treasured haenyeo’s).